|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER II

Men on Horseback

A. O. Waha was one of the first of the technically-trained foresters to be sent to the Southwest, arriving in Silver City in July, 1905, to assume his duties as Forest Assistant at a salary of $l,000 a year.

Years later Waha recalled that Supervisor McClure received him in his office, in a small brick house that was formerly a residence, in characteristic pose, "his cigar in his mouth at an angle of 45° and his thumbs in the armholes of his vest." McClure was, of course, wearing his black Prince Albert coat, which the Rangers for some unknown reason called his "go to hell" coat.

The Reserves had been transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture a few months earlier (on February 1, 1905) but McClure was still serving under his political appointment.

"While he was quite cordial in meeting me, I could not help but feel that he was not wholly pleased with my assignment," Waha recalled in recent years. "He probably was thinking that this young squirt of a technical forester was sent here 'to get my job.'"

An incident involving McClure, which had occurred some time earlier, and which Waha soon heard about "showed McClure's heart was in the right place—but which made him appear both ludicrous and ridiculous."

"I doubt if he ever lived it down," Waha said. "It was one of those things that people simply do not forget. It seems that McClure was riding horseback, and was carrying an umbrella—horsemen in those days carried a quirt and a slicker tied to the cantle of their saddle. Whether or not he actually opened up the umbrella while riding in the rain I do not know. At any rate, it was bad enough simply to be packing an umbrella while on horseback. But when he came to a pasture and saw a calf that had been born only a few hours previously and shivering in the cold rain and meanwhile bawling plaintively, McClure dismounted, wriggled through the barbed wire and on reaching the calf stood alongside with his umbrella held over it for protection against the elements.

"Evidently, so the story has it, this was too much for the mother cow grazing a few yards away. She became infuriated, and with head down chased McClure back over the fence, and the haste in which he was forced to take the fence made somewhat of a mess of his pants. Thereafter, McClure was a wiser man, but the natives could never be convinced of this."

Waha's first assignment by McClure was to take charge of all timber sale work. This was a big task since much timber that had been cut in trespass was scattered throughout the Reserve and needed to be measured for sale to the individuals who cut it and who previously had been getting their mining timbers, lumber and cordwood simply as a matter of course.

"After buying a horse, I started out on July 22 with Rangers George Whidden and Jack Case," Waha recalled. "They were two hard-boiled, hard-riding Rangers who were much older than I and who had been around considerably. Whidden had been in the Army previously and had been in skirmishes with Indians, having been stationed at Fort Custer, while Case had been an itinerant cowpuncher.

"I shall always have a sneaking suspicion that McClure had either told them to kill me off or that they themselves had planned to do so. The first day we rode 38 miles over the burning plains country. I was quite inexperienced in riding and as a result, I was so done up after this long ride, I could scarcely crawl out of the saddle, and on reaching the ground, it was extremely difficult to move, my muscles being so sore. I doubt if there was a spot on me that didn't ache.

"After the first week in the saddle, I had become hardened to riding and felt quite at ease in handling my horse."

The Rangers were required to keep a daily diary of their activities, and in addition submitted a monthly report of daily service, which they facetiously called the "bed sheet" report.

Some excerpts from Waha's diary for February, 1906, indicate the kind of conditions encountered in the timber sale work, which continued regardless of winter weather:

Saturday—February 10. Rain and snow; very disagreeable weather. As we (also Ranger Bert Goddard who later became Supervisor of the Datil and Tonto Forests) had made up our minds to start for Kingston today, rain or shine, we saddled up about 11 o'clock and started in the rain. Stopped at Fort Bayard . . . rode to Santa Rita. Decided to stay there overnight for it was already late and we were soaking wet. Watched the masked ball in the evening. Time 8 hours. Distance 18 miles.

Sunday—February 11. Still snowing and very wet and sloppy. Were in saddles at 7 a.m., rode to Teel's place on Mimbres River, just above San Lorenzo, had dinner and fed horses. Left Teel's at 12 o'clock, starting for Kingston. All went well until we struck the higher altitudes and encountered a regular blizzard. Trail very dim and snow became deeper. In Iron Creek, it was nearly three feet deep, and we had a struggle to get through. Reached Wright's old deserted cabin near head of Iron Creek at 5 o'clock; we were wet to the skin and awfully cold, while our horses were just about all in. After much consultation and arguing we decided to stay at the cabin overnight. Spent an awful night since we had no chuck and no bedding. Brought horses into cabin with us. They had to share some of their corn with us. Place was infested with trade rats. While I was dozing during the night, Goddard shot one that was on a beam directly over me, and it fell on me causing a rude awakening. . . .

Monday—February 12. The snow was very deep, practically three feet on the level, on the west side of the range, and to make traveling still worse, the trees and bushes were covered with about a foot of snow, which one could not escape. We soon became soaking wet, and then when we reached the divide, we found the snow so deep our horses could not get through. So we led them, breaking trail through thick oak brush. This leading and breaking trail was done for at least two miles or until we reached the canyon in which Kingston is located. Took the idle people of Kingston by surprise; they could scarcely believe that we had come over the Black Range.

Apparently suffering no ill effects from their experience, Waha and Goddard spent the next four days scaling and marking trees, issuing free use permits, and inspecting some land on which an application had been made for agricultural use.

|

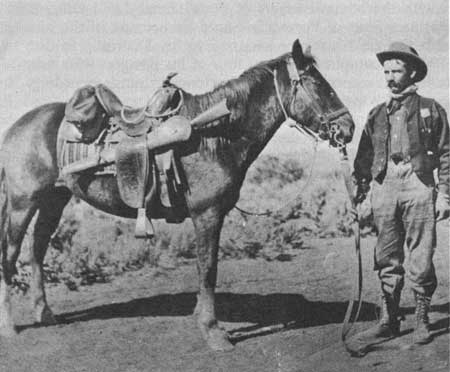

| Jim Sizer, who served as Forest Ranger and Assistant Supervisor on the Apache National Forest from 1909 to 1943. |

Waha recollected that his work on the Gila was not all confined to timber work. "In fact, I was assigned from time to time to grazing activities, mining claims, examinations, boundary surveys, special use cases and other miscellaneous work. I learned the language of the stockmen and miners. At times McClure would place me in charge of the office during his absences. On one of these occasions, I took the bull by the horns and wrote a letter to Washington strongly recommending increased salaries for Rangers, who were then receiving but $75 a month and had to furnish their own horse feed. McClure, of course, had recognized that we could not expect to retain good Rangers at such meager wage, but had not submitted any recommendation for increased salaries. In my work I was naturally closer to the men and knew their problems.

"There was Ranger Goddard, for example, with a wife and five children to house, clothe and feed, and also two and three horses to maintain. Their living conditions were far from representing the abundant life.

"Whether or not my letter brought immediate results, I do not recall, but I have in mind that it was not long before the entrance salary for Rangers was raised to $1,000 a year."

Over on the Arizona section of the Forest Reserves, much the same sort of history was being written as in New Mexico. A succession of political-appointee Supervisors and untrained Rangers were attempting to carry on the work of the Reserves in the hostile climate of pioneer cattle and sheep men, homesteaders and mining people who had previously used the Forests pretty much as they pleased.

Along with the ex-cowboys, ex-sheepherders, ex-soldiers, lumbermen, prospectors and what-not, there were, as Fred Winn recalled, a number of health seekers employed as Rangers. These had been appointed through the efforts of some obliging politician in order to permit them to regain their health by living outdoors "and at the same time working at Uncle Sam's expense on the Forest Reserves of the West."

"Taken together, most of these men served faithfully and well, under terrific handicap, as the Rangers as a class received only $60, $75 and $90 per month, out of which they were required to house and subsist themselves and to own and maintain from two to six horses and pack animals.

"They had to deal with a generally hostile population which was constantly antagonized by the wholly unfamiliar red tape of a Government located 3,000 or more miles away on the banks of the Potomac. Communications were slow because of the comparatively few roads and trails, lack of post offices, and an almost entire absence of telephones."

Unlike Supervisor McClure's problem of concise reports, Supervisor Mathew Rowe had trouble getting adequate reports from his Rangers in the Black Mesa Reserve, who were not long on letter writing or keeping up forms. A letter from Supervisor Rowe to Ranger Joe Pearse on August 25, 1899, said, "You are asked by the Forest Superintendent to give an explanation of your report of July 31. The Superintendent writes me that your report reads, 'Made report. Shod a horse. Time consumed, 10 hours.'"

Fred Breen, a former Manteno, Illinois, newspaperman, who became a Forest Supervisor in 1901, achieved a remarkable record with the Forest Service, first in Black Mesa Forest Reserve and later in Coconino National Forest. Breen ran into early difficulties with the commissioners of the General Land Office and the Superintendents of Forests in Santa Fe because of the number of health seekers who were assigned to his District. In one letter, in 1901, he complained about four of his Rangers who were "delicate in appearance" without experience in range or riding, "incapacitated for the work by lung trouble."

Nothing much was accomplished by Breen's complaints, however, until the Forest Service was organized in the Department of Agriculture in 1905 and examinations for Rangers under Civil Service became an established fact. The early Use Books outlining qualifications for Rangers pointed out that "Invalids seeking light out-of-door employment need not apply."

But even though he had trouble getting the kind of Rangers he wanted, Breen was firm in his instructions to those he had as to what was expected of them.

Some of these instructions indicate the character of their duties:

"Rangers are employed for the purpose of protecting Government land and timber.

"A Ranger's whole time is to be devoted to the interests of the government and to no other private business.

"Rangers are expected to go to a fire at once wherever one is discovered within a reasonable distance of his district.

"Daily reports should show where he went and the purpose of his visit, the distance traveled, and the time consumed each day, or if employed in burning firebreaks, piling brush, building trails, or other similar work, state the amount of work done in a comprehensive manner, that the amount may be known.

"Settlers and others are allowed the free use of timber and wood by making proper application. . . . Timber or wood secured by such application must be for their own private uses and not for sale or disposal at a profit, and must be cut under the supervision of a ranger. . . .

"Post fire warnings along all roads, trails and at springs or other camping places. . . . Nail them up securely and plentifully. . . .

"Inform yourself as to what sheep and cattle men graze their stock upon your District, the number he actually owns, and whether or not he confines himself to the range described in his permit.

"Merely riding over your District does not constitute the duties of a Ranger, but he should be on the look-out for all things affecting the Reserve, find the most exposed places and remove the debris to protect the Forest from fires, and be constantly on the alert to prevent trespasses and depredations."

|

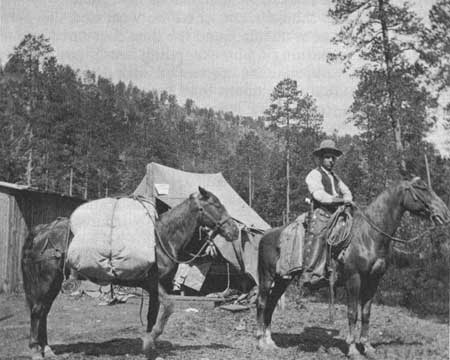

| Typical early-day Southwestern Forest Ranger, Santa Fe National Forest, July 27, 1907. |

Breen's official letters were highly informal. Writing to the Assistant U. S. Attorney John H. Campbell of Tucson in August, 1903, he said, "Am tickled to death to hear that Mr. Knave (the U. S. Attorney) is enjoying his vacation. I was under the impression from the lack of disturbance in the Territory that you also were on vacation. I had succeeded in stirring up enough disturbance to warrant my taking leave of absence. I would be very much pleased to donate you a large, juicy plug of tobacco if you could work up steam enough to inform me of the condition of all sheep trespass cases. I realize that every drop of sweat squeezed out of you is precious."

And to the Registrar of the Land Office in Prescott, Ben F. Hildreth, he wrote in October, 1903: "I return you herewith a bunch of certified-to lost souls that I have been unable to locate in this part of the country. I think all of them have left . . . and have not been heard of for the past four or five years. I hope my ironclad certificates will clinch the matter strong enough. Since I have been compelled to be a land lawyer and special agent for the Department, I am wondering what kind of a job I'll be jobbed with next. . . . If I could only have a couple Indian Reservations, a railroad, the itch, and a Waterbury watch to take care of, I really think I would be properly supplied with a few small matters to interest me now and then."

In March, 1908, Breen decided to resign and wrote a long letter of explanation to the Forester, Washington, D. C. "You see, since my salary is less now than it was about 10 years ago, after two 'promotions' in the Forest Service, I rather felt that someone was afflicted with the ingrowing salary habit, and it wouldn't be long before my creditors would notice my financial lassitude. . . .

"I thought I had a bright future before me, but that durned bright future has certainly side-stepped me along the route somewhere, and must be loafing behind.

"I was not promoted in 1905, when the transfer was made from the Land Office. I didn't think much about it at the time one way or another, but when I did get promoted in 1906, I was glad I wasn't promoted in 1905. I was getting $2371 until my promotion came along in 1906, which gave me $2200. I knew it was a promotion for my commission from the Secretary of the Interior said so right square in the middle of it.

"In 1907 I was raised to $2300; so I am still shy some of the good old salary that I started with away back in September, 1898, with only the San Francisco Mountains National Forest to handle. The fellows on the Black Mesa and Grand Canyon Forests were getting the same amount that I got; but when they fell by the wayside I fell heir to their territory and their troubles, but none of the pesos they were getting. . . .

"One can get a heap more money out of a little old band of sheep, or something of that kind, even if his intellect does not average over 30 percent, with a whole lot less trouble, and retain some friends; but with this job, the general public just naturally gets cross if you try to enforce the rules, and if you don't enforce the rules then you get cross; so the Supervisor gets the double cross whatever happens, and has no pension at the end of the game, to sorter ease down his old age when the pace is too fast.

"While I think a good deal of forestry, I realize that a man can't live in this country and lay up anything unless he gets a good salary; consequently believe I should go out and make money while I can. . . .

"I feel mightily relieved at the prospect of seeing some other feller being accused of prejudice, ignorance, partiality, graft, ulterior motives, laziness, salary grabbing and other such innocent pastimes. . . .

"I am glad there will be a bright young man here March 15, to separate me and my troubles and let me wander away to new fields, where the bleat of the sheep, the height of a stump, the brand of a cow nor even a special privilege can hop up and fill me with fright or woe. . . ."

Handling all those various jobs was pretty much a routine requirement in the early Forest Service days, as A. O. Waha was discovering in New Mexico.

"Our life was most hectic," Waha wrote in some reminiscences for Gifford Pinchot in 1940. "In making inspections of Forests on those days, we followed a very detailed inspection outline that had been prepared in the Washington office, which was most inclusive. It was contemplated that every timber sale, grazing allotment, special use permit, claim, etc., should be inspected, together with a review of diaries to determine if time was being spent advantageously, and also a check of office procedures, files, etc. Some of our reports were indeed voluminous—200 to 300 pages. Certain it is, however, when we completed an inspection, we surely had first-hand knowledge of conditions and personnel."

Recalling the first inspection he made of the Jemez, Pecos and Taos Forests, Waha said that the inspection required 30 days in the field and about a week in the office going through files to obtain data for the trip—which covered 800 miles on horseback.

"I practically killed two horses on this trip; the first one was too old, and after a couple of weeks I traded him for a four-year-old mare," Waha wrote.

|

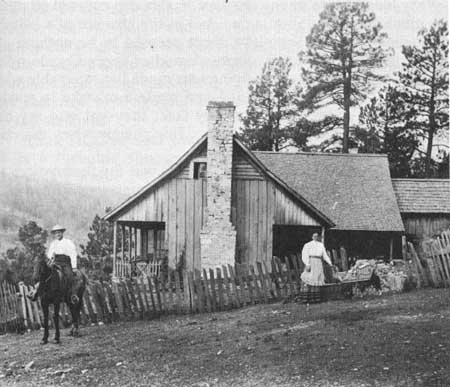

| Ranger Station in Aquachiquita Canyon, Lincoln National Forest, 1908. |

"My longest ride in any one day on this trip covered 60 miles; it was much too far to go in a day, but in the absence of a suitable place to stop over for the night, there seemed to be nothing else to do. High winds and rain storms slowed us up and made riding disagreeable, while swarms of flying ants made life miserable while they lasted. I soon learned that I had made a mistake in waving my hat to keep them away from my face; they got into my hair and it was difficult to extricate them. Fortunately when the rains came, the ants left.

"To reach Antonito, Colorado, which was my destination, the road traversed a low country that had been pretty well flooded by the heavy rains during the day. I struck this boggy section of the road after dark when my horse was so tired that he could scarcely make headway on firm ground. After floundering about, we managed to get through, and about 10 o'clock, I reached Antonito and most anxious to get some nourishment since I had only one sandwich since breakfast, which I had eaten about 5 a.m.

"To my dismay, the stores and restaurants were closed, and the small hotel had no dining servnce. So there was nothing to do but go to bed hungry, but I was too dog tired and sleepy to let this bother me unduly."

On another trip he made in the Chiricahua National Forest with Forest Supervisor McGlone, Waha encountered a situation that demonstrated what can happen when a public official overlooks the public relations side of his job.

The headquarters of the Chiricahua Forest had been moved from Paradise, a small mining town in the mountains, to Douglas. McGlone and Waha rode the mail stage from Douglas to Paradise.

"When we approached the post office and general store there were a number of loiterers on the porch," Waha recalled. "We were greeted with a yell that went like this: 'Moldy bread and moldy ham—to hell with the Forest Service,' followed by a typical cowpuncher yell.

"This was a bit disconcerting to say the least, and after we had reached the place where we were to stay overnight, I learned upon inquiry from McGlone the significance of this most unusual greeting. It seems that after he had moved his office to Douglas he had been interviewed by a newspaper reporter who had been interested in learning the reasons for transferring the headquarters. After stating the principal reasons, he went on with disparaging remarks about living conditions in Paradise, particularly the poor food that one had to put up with and made reference to moldy bread and moldy ham. Being quite naive and not having had experience with reporters, he did not realize that his remarks might appear in bold type in the newspaper. So naturally when the residents of Paradise read the paper and saw what McGlone had said (unfortunately the article gave the impression that the compelling reasons for the transfer were due to the poor food he was able to get in Paradise mentioning specifically the moldy bread and ham), they were incensed to a fighting degree. McGlone never lived down this indiscretion."

Waha recalled that besides inspections, he was often called out as a "trouble shooter." One such experience occurred in the Jemez Forest.

"The Forest Service had employed an engineer to make an accurate survey of the boundaries of one of the old Spanish land grants within the Jemez National Forest," Waha related. "As I recall the case now the engineer was drinking to excess and something was rotten in the financial management of the camp. At any rate, I was assigned to make the necessary investigation. The trip that I had to make on horseback after leaving Espanola, the railroad point, is quoted from my diary:

"January 2, 1908. At Espanola; arose at 6:30 a.m., by 7:10 I was in the saddle, and it was awfully cold. My pony which I had procured from Ranger Leese was all bowed up, but I held his head up and kept him from 'piling' me. About three miles from town up the Rio Grande valley, I met Ramon Salazar, a butcher, and another man who were going to Cañones, which I was told was close to Coyote, my destination. We didn't go by the regular road up the Chama River by way of Abiquiu but took a more direct route by road and trail across the mountains. I later regretted not taking the regular road, for we got into snow and had to follow icy and rocky trails for miles. I became awfully sore since the saddle did not fit me. It was not long after this trip that I decided to use a McClellan saddle instead of depending on any kind of a saddle I was able to rent. Having always used a large stock saddle, as did everybody else, I had to take some razzing when I changed to a McClellan. One can, of course, get saddle sore from riding a McClellan, but not nearly so sore as riding a misfit stock saddle.

"Rode like the devil when we came to fairly level stretches. Stopped at Juan Lopez's goat ranch on the Lobato Grant for dinner and also fed our horses. For our dinner we had boiled potatoes with meat, tortillas, and coffee. Since the only dishes that were set before us consisted of a cup, saucer and spoon, I ate the potatoes with a spoon and picked the meat off the bones with my fingers. We paid $.50 for the meal. The men I was riding with talked their lingo all day long and only occasionally spoke to me in English. After going down a steep-sided rocky canyon for about three miles, where the trail was fierce, we struck Cañones, a small plaza, about 3:45 p.m. My compadres left me at about 4 o'clock at a ranch where they were going to buy cattle to drive back to Espanola, and I started for Coyote, 12 miles farther west. It was quite gloomy at 4 o'clock because of the black snow clouds.

"My poor little pony was about all in, but when a Mexican caught up with me about dark, my pony took a last brace and stayed up. On the last stretch I saw a coyote about 50 yards off the road which stared at me and refused to move notwithstanding my shouts and gestures. Reached Coyote about 6:15 after having crossed the icy Rio Puerco numerous times. It was plumb dark. I went to the poolroom and found a boy who took me to Garcia's where I found a pretty squalid outfit. Only the son could speak English; he had been attending the Phoenix Indian School for three years. Had a supper of eggs, steak and coffee, all the while the whole family standing about and talking about me. After supper I went to my room where a blazing fire in the three-cornered fireplace was burning cheerfully. Talked with Garcia's English-speaking son until bedtime. Feeling better but ached all over. My horse had been well taken care of. I slept quite well.

"Sunday, January 3, 1908. Arose at 7:45 a.m. Had a greasy breakfast of fried potatoes, frijoles, an egg and coffee. Many native people in town; church bells ringing all of the time. Can scarcely walk owing to the swelling of my legs from riding. Dread getting in saddle again. It is snowing, but not enough to bother. Being only Anglo in this placita, I feel as if I were in a foreign country. Everybody stares at me. Got my horse from the corral at 11:30, paid bills and started up the canyon for Ranger Blake's headquarters. Stopped at the second adobe house where I had been told Blake made his headquarters. On knocking, door was opened by a six year-old boy and looking in the room, I saw an old decrepit man sitting on the floor alongside the fireplace. I asked him in Spanish if Blake lived here and he yelled out something which I did not sabe. Then he got up and I saw he was terribly deformed and also blind. He staggered to me and I allowed him to shake hands with me, but when he commenced rubbing his hands on my arm and I got a good look at his face which was most hideous, I concluded to 'hit the adobe' for I had a hunch he might be a leper or had some equally terrible disease. I then rode to the next house which proved to be where Blake was living. His village friends informed me that he was about 6 miles up the canyon working on a cabin. I rode up over the slippery hilly road, met Blake and after getting warm at a camp fire, returned with Blake to his house. It snowed all afternoon. Assistant Ranger Crumb came in the evening and I was glad to see him for it saved me a considerable ride. Had a bum supper cooked by native woman. Blake turned in about 7:30p.m. Crumb and I discussed the engineer affair and I had him write a statement regarding it. We turned in about 11 o'clock. At 1 a.m. Blake got up and rummaged about the room, rustling papers, going through trunks and boxes. At 4 o'clock he called Crumb and me to get up for breakfast. At 5 o'clock Blake was in the saddle, while I waited for daylight before starting out.

"January 4. Rode from Blake's headquarters on Coyote Creek to Abiquiu. About three miles from Coyote I got on wrong road which took me too far to the northwest, so I cut across a big open country to strike the right road. The coyotes were numerous and barked at me. My pony wanted to take me back to Coyote and it was necessary to fight him to keep him headed the way I wanted to go. It was a long wearisome ride down the Chama to Abiquiu. My legs ached so badly I could not stand riding out of a walk. Crossed river to Abiquiu intending to stay at Tomas Gonzales', but he was not home, so I crossed back and after much inquiry, found a stopping place at Jesus Martinez's adobe three miles below Abiquiu. Never saw so many nasty dogs as there, in and near Abiquiu. They came at us in bunches snarling and biting at my horse's heels. At Martinez's the daughter who had attended a Presbyterian mission school could speak English fairly well."

Such were the typical working conditions of the Rangers in the early days of the Service. Waha may have been a tenderfoot when he arrived in New Mexico but he was certainly learning the hard way to be a man who matched the mountains.

It was less than a couple months later that Waha was sent to the Black Mesa Forest (now Apache National Forest) in Arizona to help reorganize the office in Springerville.

|

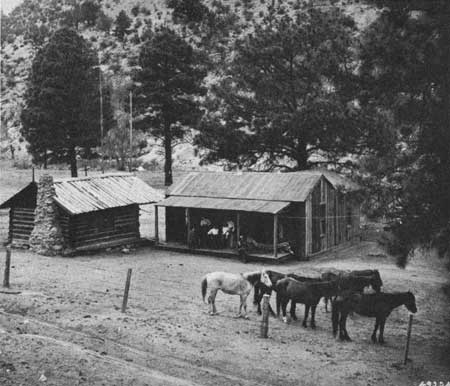

| Old and new cabins, Bear Canyon Ranger Station, Gila National Forest, 1908. |

After a week with Supervisor Martin he rented a horse to ride to Show Low, headquarters of the Sitgreaves National Forest.

"I thought I would have no difficulty in reaching Show Low by dark," Waha related. "But the day turned out to be pretty bad, high winds and snow storms, and muddy roads. I was in the saddle 13-1/2 hours; no, it was probably 12 hours, for I had to walk and lead my horse as he had gone lame in one foot and was about to give out. At 10 p.m. I decided it was impracticable to attempt going further, so I made camp on a gently rolling ridge on which there was a scattering of pine trees. First, I gathered needles and twigs and built a small fire and then rustled around in the darkness for some good-size chunks for making a big fire, since the night was cold and windy. All I could find was a rather large log and not having an axe, I had to exert all of the strength still left in me to drag it in.

"After unsaddling and feeding my horse—luckily I had brought a feed of oats on my saddle—I tied him up and then started out afoot to reconnoiter. I felt quite positive that I was on the right trail and also that I must have covered about 50 miles and should therefore be somewhere in the vicinity of Show Low. However, after scouting about for an hour or so, I returned to my camp, hobbled my horse, laid my saddle blanket on some pine needles which I had scraped together to soften the malpais rocks a bit, sat down before the fire to think it over. It was surely a lonesome night and while I managed to doze a little, I couldn't sleep. A bunch of coyotes prowling around would howl heathenishly and make one feel a bit shivery. I had a sandwich in my saddle bags which I had saved out from my lunch but refrained from eating, believing that I would be more hungry in the morning. And besides, if my horse got away from me during the night, I figured it wouldn't be so good to be afoot and perhaps lost and with no food whatever.

"Along about 2:30 a.m. I was dreamily thinking of the good bed I was missing and many other things when I realized that I could not hear my horse. Immediately I aroused myself and started out to find him, and much to my surprise, for I had thought he was about worn out, I found him about 3/4 of a mile from camp and making hurried tracks to Springerville. I brought him back to camp, tied him up and let him feed on 'post' hay for the remainder of the night. He was really good company for me and I was amused in watching him for he seemed to have me sized up for somewhat of an idiot, and by his looks I imagined he was rather sneering at me. I certainly couldn't blame him a bit. . . .

"Daylight came none too soon to suit me. I prepared a hurried breakfast, which consisted of a toasted tongue sandwich, then I saddled up and started. After riding two miles, I found myself in Show Low. I had been on the hill above Show Low when I was out reconnoitering and could have seen the town if there had been any lights in any of the houses. The Mormons had the habit of going to bed early. I arrived at Supervisor Mackay's headquarters just in time for breakfast, immediately after which I went to bed and slept until 3 o'clock.

"I stayed in Show Low two days and then hit the trail back to Springerville, but this time I made a two days' trip of it, because a Ranger with a pack outfit came halfway with me and we camped in comfort."

Probably every Forest Ranger has an unusual story to tell about being caught in a storm or having an accident while alone in the woods when he had to summon every bit of nerve and reserve stamina to make it back to help or habitation.

The late Richard H. Hanna, for many years a prominent Albuquerque attorney, served as a Ranger in his youth under Supervisor McClure and his father, I. B. Hanna, who was Superintendent of Forest Reserves for the Southwest.

In a paper he prepared many years ago, Hanna related an experience of his father's as an example of how the early Forest Officers had to be self-reliant and self-sustaining "when they traveled wild forest land and endless mesas, often far from any habitation."

"My father had a painful, and almost tragic experience once, on a field trip from Santa Fe," Attorney Hanna wrote. "He was riding by buckboard from Flagstaff to Lee's Ferry. He hobbled his team at night, but they slipped their hobbles and got away. He was still 30 miles from Lee's Ferry, but started there on foot. Father had a bad knee, resulting from a baseball injury in younger days, and after ten miles of walking, the pain in his knee became unbearable.

"He crawled the remaining 20 miles on his hands and knees. It was summertime, and he ran out of water, but he had a few cans of tomatoes that kept him going. When he finally reached Lee's Ferry at night, the ferry boat was tied up across the river; his shouts failed to arouse the people over there. He emptied his revolver before they heard and came after him."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008