|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER XXVI

The Modern Ranger

C. A. (Heinie) Merker, who spent nearly 40 years in the Forest Service before his retirement a few years ago, once said he felt there were "actually only two jobs in the Forest Service that you might say are ideal. One of them is the Ranger, and the other is the Forest Supervisor."

His sentiments have been echoed by others. Over the years the Rangers have been considered kings of their Districts, the men who run the show. Men who have gone up through the ranks invariably have the most pleasant reminiscences of the days when they were Rangers.

Some of the old-timers preferred to remain Rangers rather than accept administrative positions, and oftentimes preferred to remain in one location when they could.

Today the modern Rangers are moved around fast in various assignments, to give them experience in various Districts and operations. Organizational directories are out-dated almost before they are off the press.

While the old-time Ranger might not have had more than an eighth grade education, today's is invariably a college graduate and usually from a university with a forestry school. The old time Ranger started his job at anywhere from $75 a month to $1200 a year and had to provide his own horses and their feed. The Forest Service provided housing, such as it was—often merely shelter. Today, salaries are more in line with positions of like responsibility, and while all of the Ranger Station residences are not modern, the old ones are being replaced gradually, and new ones are being provided that are equal to homes in the better subdivisions of nearby cities.

While it used to be that the Forest Service would allot $500 to $600 to build a house—and often the Ranger had to help build it himself—today the maximum that can be spent to construct a residence is $22,000.

Henry Woodrow, long-time Ranger on the Gila wrote, in some reminiscences of his Forest Service years, that in 1912 he was allotted $75 to build a log cabin at the Ranger Station. With the $75 he hired a man to help him and they put up a cabin and covered it with shakes or boards split from a pine tree.

Edward Ancona remembers that when he first went to the Prescott National Forest in 1912 that he helped build the Willow Creek Station "with a limitation of $600 on the building construction." "I think we stayed within our $600 limit, if you can imagine building a house, a three- or four-room house for $600. It took some finagling."

The Ranger Station homes that were in existence even in the 30's and 40's were nothing to brag about. Dean Cutler, assistant chief of the Regional Recreation and Lands Division, recalls that when he first went to Reserve the house he was assigned was somewhat primitive. "We kept wondering why we'd find sawdust on the baby's blanket in the bedroom," he recalled. "We investigated and found that carpenter ants had eaten out practically the whole inside of a beam."

|

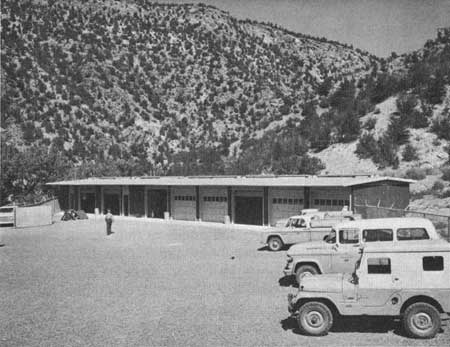

| A modern District Forest Ranger's Office, Springerville, Apache National Forest. |

When Walter Graves, chief of the Regional Operation Division, was assigned to the Coyote District of the Carson National Forest in 1939—his first assignment as a full-fledged Ranger—he found that his home would be an adobe house without electricity and with mud-plastered interior walls.

Graves continued to have house problems and recalls that of five he occupied only one was in good condition. When he was moved to the Long Valley District on the Coconino in 1944, "One of my first jobs was to enclose the back porch and construct a new front porch and then put new oak floors in the living room and front bedroom," he related. "Incidentally, I understand that about three years after I had laid these floors the termites had eaten the floors to a point that when the Ranger's wife was vacuuming one day, the vacuum cleaner fell right through the floor. We found later, of course, that the entire house was just completely eaten up with termites."

Graves' experiences with poor housing had extended back to the time when he was given a temporary appointment as Assistant Ranger under J. W. Johnson, who had been Ranger on the Pecos District for many years.

"When we moved into the house we were to occupy," he related, "I found that it was about ready to fall down. As a matter of fact, the walls along the dining room on the south side of the house had fallen away from the ceiling so that there was a three-inch gap between the ceiling and the wall. Our first job was to correct this problem. We found the roof joints in the attic had not been tied to the walls and the weight of the roof was pushing the walls out. We went in with a jack from the basement and jacked the roof up, pulled the walls back in, and tied them together.

"The next problem was the well. There was an old windmill at the corner of the old office that supplied water to the Ranger station. We found that the water was so polluted with gasoline that my predecessor had been able to bail 'water out of the well and actually burn it in the trucks.'

"I can remember that during that first winter we had a little tin stove in the office, and the way I started fires in the morning was to bail a bucket of water out of the well and throw it into the stove and toss a match in! And it burned real well.

"There was quite a lot of excitement around Pecos as a result of this. We had a number of geologists examining not only the well but the surrounding country, and the final decision was that there was a pocket of gas that had drained from some distant source into the area and that this was what we had tapped. This of course made the water completely unusable. On a hunch I sent a sample of the water to the University for analysis, and they found that there was not only gasoline in the water but there was also Bacillus coli in sufficient quantities to be very dangerous. When the Supervisor received the analysis on this, he was out at Pecos the next day locating a new well. A new well was drilled. We hit the same strata of gas about the same depth as in the old well, but this was cased off and the driller went on down several hundred feet farther and did bring in a very excellent well, which is still being used."

The well, with its stone pump house, is about the only thing at the Pecos Ranger Station that is left from early days. There is a completely new station, built in two sections in the past several years, a whole new complex of pre-fab warehouse buildings and several fairly new three and four-bedroom homes to house the professional staff members and their families. The attractive homes, well-built and well-insulated, had been moved in from the Continental Divide Training Center.

Because of his own experiences with housing conditions as a Ranger, Chief of Operations Graves is symphathetic to the needs of the Ranger staffs, but not optimistic about catching up.

"Unfortunately," he explained, "the funds that we receive for this work are very inadequate, and at the present time we are not able to do much more than meet our current needs. We are getting about enough money to construct one complete Ranger Station a year. This does not mean that we concentrate on constructing one station—office, a couple of houses, a warehouse, barn and other necessary facilities—but the equivalent of that."

The Pecos Ranger Station is one of the fortunate ones that has been rebuilt. It is also a good example of what has been happening all over the Forest Service in the Southwest in recent years. From the days when a Ranger and a couple assistants handled the work, today there is a permanent staff of 15, of whom seven are professionals—three of them, incidentally, graduates of the University of Missouri. During the summer the staff increases to as many as 60 people.

The professional foresters and the Ranger himself, Arthur Maynard, are young men—mostly in their thirties. They have 225,000 acres of forest and range to administer and protect from fires, something like 57,000 summer visitors to look after, and eight million board feet of logs to check out in timber sales.

In the old days, the Rangers covered this District on horseback. And it's still horseback country, for the Pecos Wilderness is part of it. Today, the District has a remuda of 27 horses, a fleet of trucks, a couple snowmobiles—and a heliport for helicopter landings. (The District has a cooperative agreement with the Air Force for search and rescue operations, using Air Force helicopters to bring ill or injured out of the Wilderness.)

But with all the different modes of transportation available, firefighters still find that there are a few places that they still can't reach by any means of travel except hiking in. A fire behind Penitente Peak last year took five and one-half hours to reach on foot.

The Ranger and his assistants may be better educated and better trained than the old-time Rangers, but they are still just as rugged. They are still men to match the mountains!

There are many modern Rangers who are "tall in the saddle"—of whom their old-time predecessors would be proud. There are some who have given their lives to their jobs . . . men like Rolfe Hoyer, of the Apache Forest, who was killed while fighting a forest fire, and Ken Sahlin, fire control officer on the Apache, who was killed in a plane crash. Sahlin had served earlier as a Ranger at Tres Piedras and on the Coronado.

Rolfe Hoyer lost his life fighting the Slaughter Fire in the Apache Forest on May 19, 1967. Born on a farm near Kalamazoo, Mich., he early developed an interest in the outdoors, and when he entered Michigan State University he studied forestry, and received his degree in that field. He joined the Forest Service in 1956 on the Coconino National Forest and later became an assistant District Ranger and then Ranger on the Mayhill District of the Lincoln National Forest in New Mexico. In 1962, Rolfe Hoyer was assigned to the Apache National Forest, where he served with distinction as recreation and lands staff officer until his untimely death.

Ken Sahlin was killed when he and Mayor Ernie Becker of Springerville, Arizona and their pilot were circling a small forest fire on June 25, 1962. The plane crashed and all three were killed.

An excerpt from a letter to the Forest Service staff from Mrs. Sahlin best described the kind of Ranger Sahlin was:

"Ken's life before we were married was crowded with worthwhile experiences . . . a good home, successful war record and college life. From the very first day of his Forest Service career, Ken loved to go to work—be it weekday, weekend, or three in the morning. Few men are so fortunate to find such a successful and personally satisfying way to raise and support their families. Because Ken was happy in his work, the Forest Service has my sincere gratitude. I would not have changed a minute of his life-except that last minute!"

After Sahlin's death, Mrs. Sahlin and their three children returned to Minnesota—his boyhood home—to live.

There are many other Rangers whose personal lives and work exemplify the best traditions of the Forest Service. It would be difficult to pick out the typical modern Ranger, for they come in all sizes and vary in age from the early thirties on up. Usually they have one very definite characteristic in common. They are dedicated men—with some men the Forest is almost a religion.

Mrs. Fred Swetnam, wife of the Ranger on the Jemez District of the Santa Fe Forest, has a little story that describes her husband's dedication to his job.

"We were at the El Rito Ranger District just before the birth of one of our boys," Mrs. Swetnam related. "It came time for Fred to rush me to the hospital at Espanola. On the way, he discovered some cows in trespass. There was nothing to do but stop and get the cows off the Forest and close a gate!"

"Oh, well," Fred put in, "it turned out to be a false alarm anyway."

Mrs. Swetnam is a typical Ranger's wife, or rather her experiences are typical—both of the old-time Ranger's wife and the modern Ranger's wife who usually plays a busy part in the life of a community.

They have lived under quite primitive conditions in times past, have spent 19 years of their lives on Ranger Districts, and have raised a happy family of three boys and a girl, all of them now teen-agers.

"Our place on the Lincoln National Forest at Mesa Ranger Station was the bad one," Mrs. Swetnam remembered. "The plumbing wouldn't work, the place was cold, for the stove never worked properly, and I was almost afraid to step outside with baby because of the danger of rattlesnakes. For a city girl, I can tell you it was quite an adjustment."

Mesa was a one-man duty station, so Mrs. Swetnam had to become an auxiliary Ranger—taking telephone calls, relaying orders to fire guards, spotting fires, and a lot of other duties including cooking for emergency help and visitors.

Fred himself had to do everything that is done at a District from fire patrol, scaling logs, and handling permits to typing his own letters and reports.

Quite a difference today, when he has a work force of 23 men at peak periods and a professional staff of administrative assistants.

Fred Swetnam probably best exemplifies the transition period of the Forest Service—the changeover from the rough and ready ways of the early Forest Service to the highly complex multiple-use management operation of the present.

His work today is a far cry from his years on the El Rito and Ruidoso Districts when he personally fought fires, built fences, marked trees for cutting, and all the other variety of manual labor activities of a Forest district. Today, Fred Swetnam is an executive. Under the concept of today's operation he leaves much of the leg work and the routine to work crews and subordinates. His job is to manage the operation, to make decisions, to train and supervise, to become community involved.

He is probably as proud of this last category as any, for his service on the Technical Action Panel for Sandoval County brought a Distinguished Service Award from the Department of Agriculture. Only three of 3,000 counties won such recognition for their efforts to assist the economy of the community. As one of those Rangers who has what he calls "a limited knowledge" of Spanish, he has a rapport with the Spanish-speaking community and is simpatico to their problems and culture.

But Ranger Swetnam isn't the executive to the extent that he doesn't take a personal hand in the full operation of his District's activities. Having been exposed to all the problems, predicaments and emergencies that befall men in the woods, Swetnam is on constant alert and makes a daily practice of briefing his field crews and keeping in close touch with all that goes on in the 180,000 acres under his jurisdiction.

During the fire season he is especially close to his job, and every morning as his work crews and fire patrols prepare to depart, he gives his instructions over and over again, so that every detail is understood.

The Ranger not only has to worry about lightning strikes, but also careless people, for there is a tremendous influx of people into the Jemez country every weekend.

There are 15 campgrounds on the District, and just cleaning up after the weekend visitors is a big job.

To provide for the needs of maintenance and firefighting, there is a new warehouse full of equipment—everything from old-fashioned pack saddles and snowshoes to power saws and sleeping bags, and a variety of firefighting tools.

Swetnam is proud of the many Spanish New Mexicans who have worked with him over the years and their record with the Forest Service. He is particularly proud of the fact that his District has the distinction of having a third generation of one family on the payroll. He is Carlos J. Sandoval, fire dispatcher, who returned to the Jemez District office after service in Vietnam. Carlos' father, Simon Sandoval, retired after 31 years service, mostly as Cerro Pelado lookout. Simon Sandoval's father, Pete Sandoval, was employed on the District on trail and improvement maintenance and fire control work for 13 years prior to retirement in 1938.

The Ranger Station at Jemez Springs is a spanking new one—and perhaps that is one reason the Ranger would hate to leave this District. There are three new modern homes, too, but Swetnam and family decided they'd just as soon stay in the old house, which was built in 1928. "It's kind of like having a comfortable pair of old shoes," Swetnam explained. "You hate to give them up."

Like all modern Rangers, Swetnam is college trained. He was graduated from Colorado A & M in 1950 and took graduate work in range management in 1950-51. He went to work first at El Rito Ranger District, serving as assistant to a man he considers a great Ranger—Paul Martinez—then had three years as Ranger on the El Rito and Ruidoso Districts, and seven years at Penasco, headquarters of the southern district of the Carson National Forest, before being assigned to the Jemez District on the Santa Fe National Forest. On the Jemez he follows such outstanding Rangers as Leon Hill, Perl Charles and Len Lewis. Lewis, who had succeeded Charles in 1935, was killed November 1, 1938. Starting out at night with a truck and horse trailer for a camp where he would start a range and game survey next day, Lewis's truck and trailer slipped off a narrow curve and plunged down into Jemez Canyon. Both Lewis and his horse were killed. He was survived by his widow and nine children. They continued to make their home at Jemez Springs during the succeeding years.

|

| Modern buildings and equipment at the Jemez Ranger Station, Santa Fe National Forest. |

Talking about the difference between the old-time Ranger and the modern Ranger, Swetnam's superior, John M. Hall, Supervisor of the Santa Fe National Forest, thinks that the essential difference is that the old-time Ranger was strictly an outdoorsman. He carried on much of his job outdoors. Today the Ranger is a desk man by necessity. "I don't mean that he doesn't get out," Hall explained, "But the paper work and management problems tie him to his desk a great deal of the time. It's rare that I can't pick up the telephone and find one of my Rangers at his desk."

Supervisor Hall is something of a rarity since he skipped the Ranger phase of a career in the Forest Service. He had started as a timber scaler, then went into wildlife management and was for a number of years State Game Warden of Arizona before returning to the Forest Service in administrative work. But he is a strong booster for his Rangers and stresses the importance of the Ranger's job.

"It's the key to the success of the Forest Service," Hall said.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap26.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008