|

A History of the Salmon National Forest

|

|

PART 2

SALMON NATIONAL FOREST, ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT

A. CREATION OF THE SALMON NATIONAL FOREST

The Salmon River Forest Reserve was established by Proclamation of President Theodore Roosevelt on November 5, 1906. This Reserve was bounded on the west by the total length of the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, with Marsh Creek and Valley Creek on the southwest. The Salmon River formed the southern boundary, from Valley Creek east to Thompson Creek. From Thompson Creek north to the North Fork of the Salmon River the line followed approximately the present boundaries of the Challis and the Salmon National Forests as they more or less parallel the Salmon River, then followed west down the Salmon River to the Middle Fork.

Later Presidential Proclamations and Executive Orders added lands or eliminated lands from this original Salmon River Forest Reserve. The name Forest Reserves was changed on March 4, 1907, to National Forests.

President Theodore Roosevelt's Executive Order No. 841, effective July 1, 1908, added to the Salmon National Forest the area north of the Salmon River from and including the drainage of Boulder Creek, which enters the Salmon River from the north at Shoup, west to and including the drainage of Horse Creek. This area had been part of the Bitterroot Forest Reserve established in 1897 by Proclamation of President Cleveland. Also added to the Salmon National Forest by Executive Order No. 841 was that portion of the Lemhi National Forest directly east of the addition from the Bitter Root Reserve: north of the Salmon River east of the Boulder Creek drainage to the Continental Divide, south to the Lemhi Indian Reservation near the drainage of Agency Creek. Also transferred from the Lemhi National Forest was the Lemhi Mountain range south to Bell Mountain, exclusive of the Pahsimeroi drainage.

This same Executive Order separated from the Salmon National Forest those lands south of lower Camas Creek to Yellow Jacket Creek, and that part south of Yellow Jacket drainage, south of the Panther Creek drainage, and south of Hat Creek drainage, creating the Challis National Forest.

The Idaho Enabling Act, July 3, 1890, reserved for the State of Idaho title and claim to sections 16 and 36 in each township as grant-in-aid to common schools. These school sections sprinkled throughout the National Forests presented a potential management problem. However, in the Salmon National Forest, as in other National Forest areas that had not yet been surveyed, the title or claim of the State did not attach (the State did not take title to these lands) because of the lack of an accepted survey, and an adjustment was made whereby the State accepted, or would accept, other lands "equivalent in acreage and value lying along and within the boundaries of said National Forests, in such position that, when eliminated therefrom, all of said selected lands will lie outside the new exterior boundaries of the National Forests..."1

1A Proclamation No. 1235 by the President of the United States of America, dated March 3, 1913. p. 1.

A memorandum of agreement was entered into on October 4, 1911, between the Secretary of the Department of Agriculture and the Governor of the State of Idaho. The lands involved in these transactions have become known as "lieu lands" because the State accepted them in lieu of their designated lands with the National Forest boundaries.

Proclamation No. 1240, dated May 19, 1913, by President Woodrow Wilson made further boundary changes, transferring lands north of Camas Creek and west of Meyers Cove, plus the Silver Creek drainage, from the Challis National Forest to the Salmon National Forest, primarily T18N, R17E. A portion of Little Hat Creek drainage was transferred from the Salmon National Forest to the Challis National Forest, lying in the S.E. portion of T17N, R19E. That part of the Salmon National Forest south of Lemhi Union Gulch, T12N, R27E, in the Lemhi Range, was transferred to the Lemhi National Forest. Most of the Beaverhead Forest lying west of the Continental Divide, from Chamberlain Creek (Lemhi drainage) northwest to the head of Peterson Creek, became part of the Salmon National Forest. Along the borders of the Salmon Forest many small areas were eliminated, to be restored to settlement and entry.

More transfers of land took place in 1926 when President Calvin Coolidge issued Proclamation No. 1769 on March 24. Transferred to the Salmon National Forest from the Idaho National Forest (now the Payette) was the area west of the Middle Fork, south of the Big Creek drainage, to but not including Norton Creek drainage, including all of the drainage of Brush Creek and west to Shellrock Peak. One very small part of the drainage of Cub Creek in this area was transferred to the Salmon from the Payette National Forest, being in section 5, T17N, R14E.

By Proclamation No. 1922 of President Herbert Hoover, September 25, 1930, the drainage of the North Fork of Morgan Creek (Pahsimeroi drainage) was transferred from the Salmon National Forest to the Lemhi National Forest.

October 8, 1938, Executive Order No. 7986 abolished the Lemhi National Forest. The following lands of the Lemhi National Forest were transferred to the Salmon National Forest:

T12N, R27E, that part south of Lemhi-Union Gulch

T9-11N, R28E.

T7-10N, R29E.

T12 and 12 N, R29E

T7-13N, R3OE

T9-13N, R31E T8-14N, R32E

These lands were the Medicine Lodge District of the Salmon National Forest. They were transferred in 1948 to the Targhee National Forest.

Executive Order No. 8355, dated February 25, 1940, by Franklin E. Roosevelt, transferred the following lands to the Salmon National Forest from the Idaho (now the Payette) National Forest: lands lying east or north and east of a line beginning at the forest boundary on Salmon River at mouth of Cottonwood Creek and extending up Cottonwood Creek to the mouth of Basin Creek; thence up the ridge between Basin Creek and Peak Creek to Cottonwood Lookout; thence following the divide between Papoose Creek and Cottonwood Creek drainage to Farrow Mountain; thence south and east along the divide on the west side of Papoose Creek drainage to the forest boundary on the Middle Fork of Salmon River. These areas west of the Middle Fork which came to the Salmon National Forest in 1926 and 1940 from the Idaho Forest were originally a part of the Bitter Root Forest Reserve in 1902.

The present (1973) total area within the boundaries of the Salmon National Forest is 1,790,999 acres. This includes approximately 23,140 acres which are not National Forest, being private or state land. The main body of the Salmon National Forest is in Lemhi County, with a small portion (65,578 acres) in Valley County, and a smaller portion in Idaho County. The Challis National Forest and Targhee National Forest extend into Lemhi County.

Because the public was not conservation minded in the early 1900's, President Roosevelt widely publicized the work of the Forest Service, enlisting the cooperation of local and state groups throughout the country. In 1907 he called for a national conservation conference at the White House, which focused the attention of the nation upon the problem of conservation, giving prestige to the Forest Service.

There is some hostility in the West to the United States Forest Service because it affected westerners directly and seemed to be infringing former freedoms. An article in the Lemhi Herald for December 6, 1906, set forth the principles and aims of the Forest Service.

.....The government declares that the administration of Forest reserves is not for the benefit of the government but of the people.....This forest force has two chief duties; To protect the reserves from fire and to assist people in their use.

Persons having valid claims under the public land laws or legal title to land within forest reserves are free to occupy and enjoy their holdings,... but must not cut timber or make use of forest reserve land without a permit, except within the limits and for actual development of their claims. Any other use will constitute trespass. The forest service will grant preference in the use of privileges to actual residents in or near forest reserves....

Prospectors for mineral may have free use of the reserve, provided they limit their use of timber to the actual needs of prospecting. And no claim of any kind can be held valid because of its containing valuable timber....Any mining concern, employing men on wages, must pay for the timber. No rancher can freely take timber off a reserve, unless it be shown that he has not suitable timber growing on his ranch. But when the prospector or rancher exceeds these limits he must first procure a permit and pay for the timber used. All brush must be piled and burned.....

The free-use material. . .will be refused to sawmill men. . .or commercial enterprises. . . .No free-use material is allowed to be sold.

Timber is for sale and applications to purchase are invited. Anyone may purchase except trespassers upon the public domain. All timber must be paid for before it is cut. . . .No living trees can be cut until marked by the forest officer. Violation of these rules constitutes trespass.

Wild grass upon forest reserves may be cut for hay under permits issued by the supervisor. A reasonable charge per acre may be made. . . .

The secretary of agriculture has authority to permit, regulate or prohibit grazing in forest reserves. In new reserves, where the livestock industry is the big thing, full grazing privileges will be given at first, to all who pay the required fees, and if reduction in numbers is afterward found necessary, stockmen will be given ample opportunity to adjust. . . .The leading objects of grazing regulations are to protect and conserve all reserve lands adapted for grazing, to work permanent good to the livestock industry through proper care of the grazing lands. . . .all persons must secure permits before grazing any stock in a forest reserve, except the few head in actual use by prospectors, campers and travelers, and not to exceed six head of milch or work animals owned by a bona fide settler; these latter require no permit.....

Applicants for grazing permits will be given preference in the following order:

Small near-by owners,

All other regular occupants of the reserve range.

Owners of transient stock.

Applications of new settlers will be considered except when the range is already fully occupied by small owner....

Anyone grazing stock without a permit is a trespasser, and no trespasser can procure a permit. . . .

A reasonable fee will be charged for grazing all classes of livestock. The minimum price will be 20¢ to 35¢ per head for cattle and horses for the summer grazing, and 35¢ to 50¢ for the entire year. Sheep will pay 5¢ to 8¢ per head for summer. . . .

The Herald has gathered the foregoing from the "Use Book" issued by Forester Pinchot, fully defining the regulations and instructions for the use of forest reserves. Lemhi is already in such reserve, and another season will bring 2 or 3 supervisors and about 20 rangers to take charge of the country. It is appropriate that the people should be informed upon the practical side of the subject.1

1"Rules and Regulations Over Forest Reserves," The Lemhi Herald, December 6, 1906, p. 1.

Opposition arose among the local people, as reported three weeks later:

TO OPPOSE THE FOREST RESERVES OF LEMHI.

Citizens Prepare the Way For a Monster Petition and Memorial to the President. Citizens Unanimous in their Disapproval.

. . . .The feeling of remonstrance is very general. . . .an informal meeting of a few citizens laid plans for covering the county with copies of a petition. . . .We the undersigned citizens and residents of Lemhi county, state of Idaho, hereby protest against the action of President Roosevelt in creating the new forest reserves in Lemhi county. We regard the step thus taken as ill-advised, unjust and directly contrary to the best interest of the state and its people.2

2"To oppose the Forest Reserves of Lemhi," The Lemhi Herald, December 27, 1906, p. 1.

The petition included the following points:

a) This is not a timber country: there are no valuable tracts of timber which require protection.

b) The indigenous trees will never be of commercial value. Any timber in the reserves will be needed for local wants.

c) The country is so precipitous that the sources of the streams can never be denuded of timber. The forest belts are generally on high rocky, precipitous land that is practically inaccessible.

d) The stock ranches here are all small and the ranchers unable to afford the expense of permit grazing.

e) The restrictions of the reserves will hinder prospectors and miners.

f) The fees imposed for maintenance of the reserve is purely local, while the benefits, if any, are for the country at large.

g) Wood for fuel is already expensive and hard to get, without this additional cost.

h) This thing has been done without the knowledge or consent of the people directly affected.

The petition concluded by asking an agent of the forestry bureau to come to investigate and to consult with the local men.

In March, 1907, Major Frank A. Fenn, Supervisor of the Forest Reserves in Idaho, came to Salmon, met with stockmen and other interested people, to explain the relation of the Forest Reserves to the people. Over 100 people attended. Mr. Fenn explained that the current haphazard method of using the range would mean destruction of the livestock industry within the next ten years. All admitted that the ranges were overstocked, yet nobody but the government would be able to take hold of the matter in the cause of the public welfare. The time had come when somebody would have to equalize the range-rights, or somebody would suffer. Fenn stated that the government planned to improve and protect grazing ranges within the forest reserves and maintain public grazing range to the highest state of productivity.

Fenn set forth the objects of the forest timber policy:

a) to protect the remaining forests from ruthless slaughter,

b) to reduce loss from forest fires,

c) to guard the heads of streams and conservation of the water flow.

Fenn explained that the dominant industry is always considered first (cattle, sheep, lumber, etc.) and in this way the old time range war should be a thing of the past. In the first year there would be no restriction on herds that had habitually ranged on the forest. No new stock would be allowed. After the first year the range would be examined and adjustments in grazing permits made according to the condition of the range. In reducing numbers of livestock on a district, the men would be asked to decide among themselves. If they could not agree, the supervisor would settle it on a prorata basis.

Major Fenn told of his meeting at Junction (near Leadore) and that the men of the upper Lemhi organized, with the following elected to the advisory boards to adjudicate differences: Herbert H. Hays, chairman, Thomas Yearian, secretary, Gray L. Purcell, George W. Cottom and Michael Maier.

Major Fenn answered questions and at the close of the meeting it was plain to see that most of the group had a more hopeful view of the forest reserves and felt the ranchers would eventually realize much benefit from this service.1

1"Talks on Forest Reserve Rules," The Lemhi Herald, March 7, 1907, p. 1

Frank Fenn was well chosen to represent the Forest Service to the people of Idaho because he had been an Idahoan for many years, was a member of the first legislature, and the people knew him and respected him.

On February 28, 1907, it was announced that George G. Bentz had been named Superintendent of the Salmon Forest Reserve, and on March 7 of the same year he opened his office in Salmon.

Earlier in 1907 the following poem was published:

ODE TO FOREST RESERVES

(From the Poet Lariat — January 10, 1907)If all the trees in all the woods were men,

and each and every blade of grass a pen;

If every leaf on every branch that quivers

Were turned to foolscap; Salmon and Lemhi Rivers

Were changed to ink, and all the local tribes

Had nothing else to do but act as scribes;

And for a thousand ages, day and night,

These hoodoo's souls should write, and write, and write,

Till all the pens and paper were used up

And the great inkstand were an empty cup;

They could not terminate their dissertation,

Or half-express their mighty indignation

At what they term a curse on all creation —This bureaucratic forest reservation —

Applied to plains where forest never moan,

Where only sage and bunchgrass hold their own;

While coyotes follow where the cattle went,

And gray wolves chorus in a mad lament,

And deadly hemlock cleans up ten per cent.

Still would the scribblers cluster round the brink

Calling for more pens, more paper, and more ink.

B. PERSONNEL

Personnel records for the earliest years are incomplete. In June, 1907, The Lemhi Herald carried a report on the Forest Service and listed the following employees:

Supervisor: George Bentz

Assistant Supervisor: William Swan

Guards and Rangers, and their areas:

Ora Cockrell — Salmon City

Montie Buster — Sunfield

H. B. Weber — Lemhi Agency

F. W. Carl — Gibbonsville

Earl Gilbreath — Big Creek (Panther Creek) and Shoup

R. W. Young — Shoup

E. M. Christensen and Ashton — Prairie Basin (Forney)

H. D. Gerrish and Ross Tobias — Challis (The Salmon Forest Reserve at this time included much of the present Challis National Forest)

Wm. Shanafelt — Salmon River

George Nichols — Predator hunter in the Junction area

Jas. M. Ryan was being recommended for appointment as a ranger

Mr. Swan reported a need for two good timbermen at Salmon, a ranger for Loon Creek, one for Stanley Basin and one for Greyhound, and the Salmon office needed a clerk and a map maker. The Herald reported that these forest officers are endeavoring to get their stations established, cabins built and equipped, and the mountain trails opened from one district to another. Mr. Swan pointed out that after the force gets strung out it will be next to impossible for stock-rustlers to go through without being spotted and stopped. Strayed stock will be reported and recovered, and a close check will be kept on forest and range fires.1

1"Local Forest Service," The Lemhi Herald, Salmon, Idaho, June 27, 1907, p. 1.

The Salmon National Forest is part of the Intermountain Region with headquarters in Ogden, Utah.

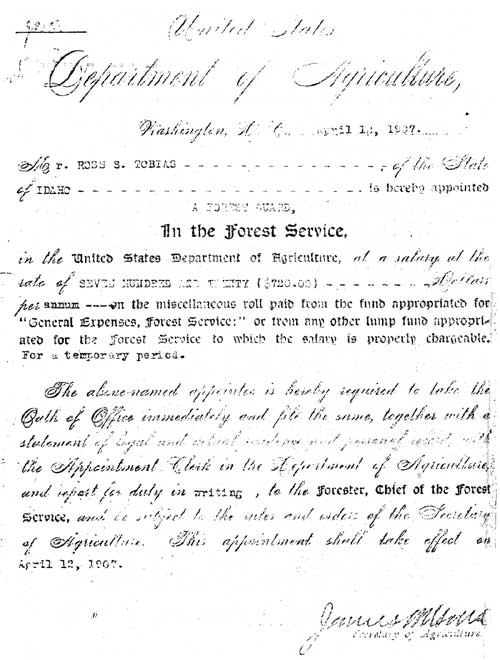

Early Salmon Forest employees Fred Carl, Ross Tobias, and Fred Chase each tell about taking the Civil Service Commission test for ranger. In addition to the written test there was a field test, administered in a field on the bar near what is now Broadway and Third, about where Ikey's Beauty Shoppe now stands. Each applicant was required to make a plat of a piece of ground, pace off a certain distance, saddle a horse, use a diamond hitch in packing a mule, and pass a test of target shooting and use of a gun. In 1907 the salary for a Forest Guard was $720. per year, soon raised to $900., and in 1909 the annual salary for Assistant Ranger was $1100.1

1Interviews: Fred Carl, Salmon, Idaho, May 1, 1969; Ross Tobias, Salmon, Idaho, May 27, 1970; Fred Chase, Boise, Idaho, June 1, 1970.

Fred Chase reports the following location of personnel in 1909:

Indianola — R. W. Young

Hughes Creek — Ora Cockrell

Salmon — Wm. Swan and Fred Chase

Lemhi — George Ashton

Forney — Morris Christensen

Junction — Harry Long

Ross Tobias started work for the Salmon Forest Reserve in April, 1907, at the age of 21, as a Forest Guard, and was later promoted to Assistant Ranger. His certificate bears the personal signature of Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson. Tobias worked on the Lemhi and Junction Districts in 1909, and in 1910 went to Cabin Creek Station at Forney. Earl Gilbreath was at Forney that year, and Gus Schroeder was at California Bar (Leesburg). The name A. L. Dryer appears in the Tobias diary in 1913 at California Bar.2

2Ross Tobias, Forest Service Day Book, April 1907 — September, 1913

Otis Slavin remembers that in 1914, the Leesburg Ranger was Ray Dryer, with Clarence McCracken as assistant. Otis Slavin and Paul Stratton worked on trail crew under McCracken.3

3Interview with Otis Slavin, Boise, Idaho, July 18, 1969.

A 1915 map of the ranger districts of the Salmon National Forest shows 12 Districts:

1. Indianola — R. E. Allan

2. Hughes Creek — Ora Cockrell

3. Fourth of July Creek — C. J. Kriley

4. From Sal Mt. up the east side of the Salmon River to the Pahsimeroi — F. C. Haman

5. Leesburg (California Bar) — R. L. Dryer

6. Forney (Cabin Creek) — J. Gautier

7. From Carmen to Hat Creek, west of the Salmon River — Wm. Swan

8. Shoup (Garden Creek) — M. E. Mahoney

9. Lemhi, surrounding the Indian Reservation — G. R. Ashton

10. Leadore area, west of Leadore — Fred Chase

11. Junction, Grizzly Hill area which had been the Idaho part of the Beaverhead National Forest — C. Nelson

12. Gilmore — H. B. Weber

(click on image for a PDF version)

Later the Leadore and Junction districts were combined under Fred Chase, and the Gilmore district was later added.

A more complete roster of forest personnel is listed in the Appendix. Salmon National Forest, Total Permanent Full-Time Employees:

| 1957: | 20 | 1964: | 64 | |

| 1958: | 23 | 1965: | 52 | |

| 1959: | 32 | 1966: | 50 | |

| 1960: | 42 | 1967: | 54 | |

| 1961: | 45 | 1968: | 52 | |

| 1962: | 55 | 1969: | 50 | |

| 1963: | 65 | 1970: | 55 | |

| 1972: | 62 | |||

Accidents Fatal to Forest Employees

Herbert G. McPheters, assistant supervisor, was killed in May 1962. He and a foreman were returning by truck to a Forest road crew near Morgan Creek when mechanical failure caused the truck to run off the Salmon River road about 25 miles up river from Salmon. McPheters was killed and the foreman survived.

A CCC enrollee from Camp F-401, Ebenezer Bar, was killed in the spring of 1939 when struck by a rock dislodged by the spring thaw.

Clarence Schultz, forestry foreman at CCC Camp F-401, Ebenezer Bar, was killed by lightning on July 11, 1939. Returning by trail from a forest fire which they had extinguished in German Gulch, tributary of Pine Creek, Mr. Schultz and two CCC enrollees, George Lawrence and Jay Morris, were struck by lightning. Morris and Lawrence recovered.

In 1941 a summer employee died during fire training camp on Papoose Creek, tributary of Squaw Creek. He was not well, became confused and wandered from the group. An all-night search was conducted. His body was found the next morning.

Frank Gibson, member of a trail crew working in the Middle Fork area in the 1950's, drowned while attempting to ford the Middle Fork on a horse.

In 1956, Otto Crooked Arm, member of an Indian fire-fighting crew, was killed on a fire on the head of Trapper Creek, tributary of Papoose creek west of the Middle Fork. He was struck by a rolling log.

Two firefighters lost their lives during the Corn Creek fire in 1961. One died of a heart attack, and the other was killed in a highway accident enroute home to McCammon after the fire. Though he was not on the Salmon Forest at the time of the accident, he was still on the Forest payroll.

In 1964 a TBM plane crashed while spraying for spruce budworm. The pilot was killed.

Gary Yule and John Jones were killed June 25, 1970, when their Forest Service vehicle went into the Salmon River near Indianola during high water. Two other employees riding in the truck survived the accident.

C. ADMINISTRATION OF THE SALMON NATIONAL FOREST

As the responsibilities of Forest Service officers increased, so did their regulations and instructions. One of the earliest "Use Books," published in 1907, had only forty pages, setting forth the purpose of the National Forests and the terms of their use by the public. A Use Book of 1918 was 168 pages. The 1928 manual was two and a half inches thick and today the Forest Service regulations fill many volumes.

In 1944 Inspector J. N. Kinney called attention to the uniqueness of the Salmon Forest among the Forests of Region Four because of the isolation of the Salmon; seven of the eight ranger districts comprise an isolated unit detached from surrounding economic, topographic and political areas.1 Kinney considered the Salmon Forest as an ideal unit for a social, economic or political study, which would show its economic and social relationship to the dependent community.

1J. N. Kinney, "Inspection Report," May 13, 1944, p. 1.

In 1947 General Inspection of Nord and Moncrief reported:

The Salmon National Forest is a big, important unit in good condition, well staffed, and well run. Its two million acres of rugged mountains form a major part of the Salmon River watershed and contain a fish and game resource of national importance. Its forage supports a sizeable agriculture economy with some 13,000 cattle and 36,000 sheep under permit. Sustained yield of merchantable timber is considerably more than adequate for the fuel, wood, lumber, and pole needs of the local population. It has been and still is a big producer of mineral wealth.

The Salmon and its people have a character of their own. They are independent, self-sufficient, and at the same time progressive. Since the days of Lewis and Clark they have been pioneering. . . .

Most unsolved Salmon problems are interesting because they tie in so closely to this traditional character. They are primarily problems of taming and using, and yet preserving, the pristine wilderness.

The Salmon is a back-country forest, but is managed and used by an alert and forward-looking staff and public. Its greatest products will always be water for distant farms and communities, together with wildlife and other recreation values which are not measured in dollars. Therefore, the fact that the cash receipts are considerably lower than expenditures cannot be used as a measure of its importance.2

2Nord — Moncrief, "General Inspection Report," August 5, 1947.

1. Administrative Sites and Improvements

Ross Tobias, who started as a Forest employee in April, 1907, recalls that the earliest Forest headquarters in Salmon was an upstairs office on the north side of Main Street, in the Brown block near Center Street, later known as the Cavaness Building. Forest Service headquarters were later moved across Main Street to an upstairs office in the present McPherson building. New headquarters were built during the 1930's at Union and McPherson. In October, 1965, the Salmon National Forest moved into a new building north of Salmon, on the east side of U. S. Highway 93, retaining their Union Street property for Ranger District Headquarters, warehouse and storage.

Ranger or Guard Stations before 1908 were likely to consist of a tent platform and frame with a wall tent stretched over them. Ross Tobias remembers that during his first six months in the Forest Service (1907) he never had a meal in a house unless he stopped in at a mine like the Lost Packer for a dinner. He had no cabin; just camped out all the time. One of his early jobs was to survey the boundaries of the Salmon River Forest Reserve. He and Ora Cockrell went to Loon Creek, out past Custer and clear to Marsh Valley.

As soon as possible after the establishment of the Salmon River Forest Reserve, cabins were built for the personnel in the field. However, no more than $500. was allowed to be spent on any one building. By 1919 a limit of $650. was allowed to build a ranger's home on his ranger district.

Many of the earliest ranger cabins or guard stations are not in existence today, and some have been replaced by newer structures. Some of the old-timers have reminisced about a few of the earlier buildings.

On May 25, 1907, Ross Tobias rode to Opal Creek to locate a possible site for a Ranger Station.

In November, 1907, Ross Tobias assisted Ranger Dave Laing and Guard Gerrish in surveying for the Ranger Station on Loon Creek.

Ora Cockrell built the first station at Hughes Creek in 1909.

Fred Chase remembers a Station up Pattee Creek in 1909.

At one time there were two ranger districts near Junction. One was in Region 1, administering that part of the Beaverhead National Forest west of the Continental Divide and in Idaho; the other was a ranger district in the old Lemhi National Forest. In 1913 most of the Beaverhead Forest west of the Divide was transferred to the Salmon, adding a new district. Later this district became part of the Leadore District.

In the spring of 1910 Fred Chase and Gus Schroeder built a ranger station at the forks of Jesse Creek, and fenced about 40 acres. The snow was deep and they used a sleigh and team. The Jesse Creek site is presently used as a storage area and horse pasture.

The Gilmore Ranger Station was a little below Gilmore, near the Gray Purcell ranch. Harry Coleman lived at a "fire station" on Eightmile Creek near the old Bohannon ranch. The Forest had 40 acres there and kept fire tools and equipment at the station.

Ross Tobias and Ranger Long rode from Tendoy (Lemhi) Station in August, 1909, to Alder Creek, found U. S. Survey corners and surveyed for a ranger station.

Before the ranger station was established at Yellowjacket, about 1924, the ranger's headquarters for that district were at the Mormon Ranch on the Middle Fork. Money was allotted to build a district headquarters for the Middle Fork district at the mouth of Camas Creek, but in 1924 Inspector C. N. Woods noted that place was very dry, with little forage; timber was not handy; there was no chance to buy hay for delivery there; and it was in an out-of-the-way corner of the district. C. N. Woods authorized Supervisor Scribner to construct headquarters on Yellowjacket Creek, since it was more central, with wagon road and telephone.

The Forney Ranger Station was changed from Cabin Creek to Copper Creek in 1920. Al Wheeler and Earl Kingsbury built the new station across the road from Dummy Creek (now Cobalt). Al Wheeler was the first ranger to occupy it.

When the Medicine Lodge District was part of the Salmon Forest, from 1938 to 1948, the summer home of the ranger was Warm Springs Ranger Station, 34 miles from Dubois. Also on that district were the old Kaufman station and Coal Kiln ranger station.

In 1941 the name of the Tendoy ranger district was changed to Lemhi.

At various times the ranger district boundaries were changed for administrative purposes. In 1915 there were twelve ranger districts. These were combined in various ways to eight in 1916, seven in 1923, eight in 1938 with the addition of the Medicine Lodge District, seven again in the 1950's, five through the 1960's and at present the Salmon National Forest is administered by four ranger districts.

2. Communications

One of the first management objectives after the creation of the Salmon River Forest Reserve in 1906 was to establish a communication system.

a) Mail was one of the first means of communication used. This proved inadequate during times of forest fire.

b) Runners were used in times of fire or other emergency. Runners went by horseback if there were trails, but often went on foot if the country was too rough for a horse.

c) Telephone. In some places telephone lines were built before there were rangers' cabins. There was already a telephone line from Salmon to Leesburg, completed in July 1906, owned by the Shoups.1 In August of 1907 Salmon was connected with the outside world when H. J. Bagley of Baker completed a line to Dubois and connected with the Bell long-distance system, and people of Lemhi County could talk to outside points. Salmon telephone headquarters were in Pyeatt's drugstore. The stations along the line included Salmon, Baker, Sunfield, Rees' Store (Lemhi), Junction, Gilmore, Weimer's Camp, Wood's stock ranch, Reno, Liddy's sulphur springs and Dubois. The Farmer's line from Yearianville to Bannister was an important side convenience.2

1The Lemhi Herald, August 1, 1906.

In October, 1907, it was reported that the Forest telephone line between Forney and Challis was nearing completion and later that fall F. C. Wells, forest construction engineer, and Earl Gilbreath of the Forest Service went to Shoup to inspect the route for a telephone line to Indianola. Fred Carl reported a line was planned up the North Fork, while Newton Hibbs and Willard Rood were assigned to build a line from Leesburg up Arnett Creek to Big (Panther) Creek. In November 1907 there was an estimated 325 miles of phone line in operation in Lemhi County and the contemplated Forest Service lines would bring this to 400 miles.3

2The Lemhi Herald, August 15, 1907.

3"Notes on Forest Progress," The Lemhi Herald, November 28, 1907.

Fred Carl recalls that one of his first duties as ranger on Hughes Creek was stringing telephone lines.4 Ross Tobias worked on the Indianola-Blue Nose phone line in 1912, along with Rangers R. E. Allan and R. L. Dryer.5 In 1916 the Salmon City and Western Telephone Company, which had operated a grounded telephone line from Salmon to Leesburg and Yellowjacket, owned by the Shoup's turned their interest over to the Forest Service.

4Interview with Fred Carl, Salmon, Idaho, April 30, 1969.

5Ross Tobias, Forest Day Book Diary.

The following report on telephone lines of Lemhi County in 1917 was prepared for the military during World War I by Salmon Forest Supervisor Dana Parkinson.

Lemhi Telephone Company:

—One metallic copper circuit, Armstead, Montana to Salmon, Idaho.

—One grounded copper circuit, Armstead, Montana to Salmon, Idaho.

—One metallic copper circuit, Leadore to Gilmore.

—One grounded copper circuit, Leadore to Gilmore.

—Various rural lines.

Forest Service wires:

—Metallic circuit, Salmon to Indianola Ranger Station.

—Grounded circuit, Indianola to Shoup and to Blue Nose Mountain.

—Grounded circuit, Northfork to Gibbonsville, with lateral along Hughes Creek and Ditch Creek.

The following Forest Service wires connect at a ranch house near

Forney, with rural lines operated by Lemhi Telephone Company:

—One grounded circuit, Forney to Challis. At Challis the

Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company has wires

connecting with outside points.

—One grounded circuit, Forney to Meyers Cove.

—One grounded circuit, Forney to Yellow Jacket.

—One grounded circuit, Forney to mouth of Big Creek (Panther Creek), and later to Shoup.

The Forest Service built and maintains a telephone line to Cathedral Mountain to the Lookout there, for fire protection.

No telegraph lines.1

1Dana Parkinson, "Reconnaissance Report for the Military Information Division," 1917.

A Forest Service telephone line was built from Salmon to Taylor Mountain via Lake Mountain in 1918. It was largely a "tree line" built on existing trees. Otis Slavin, who began working for the Forest Service in 1914, recalls working on this line in 1918, until he entered the army, when he was replaced by J. L. O'Quinn from Cabin Creek.2

2Otis Slavin

In 1924 the Forest Service owned no lines in the Lemhi River watershed. The two ranger stations in this area used the commercial line available. The Salmon Forest developed two separate telephone systems down the Salmon River, with one on the north side and one on the south side, and a fire dispatcher located at Cove Creek. By 1924 there were 305 miles of telephone line on the Forest. In 1928 new telephone line was built between Middle Fork Peak and Yellow Jacket Ranger Station. This connected the westernmost point, Two-Point Lookout between the Salmon and the Idaho (now Payette) with the main phone line to the east.

Early telephone lines used the "fixed tie:" the line was firmly attached to each insulator which in turn was fastened hard and fast to the tree or pole. A tree falling across the line would break it. A Forest Service employee developed the "split insulator" which allowed the line to go through without being fastened to it. Also, the insulator was fastened to the tree in such a way that if a tree fell across the line, the insulator would come off the tree before the line broke.

A portable phone was used by travelers along telephone lines. It was about the size of a three battery flashlite and used a buzzer instead of bells.

Telephone was the main form of communication in the days before radio.

d) Heliograph was early used by lookouts in reporting fires. The heliograph used the sun's rays reflected on a mounted mirror to send messages by Morse code. Some of the drawbacks in the heliograph: stations sending and receiving had to be within visible distance; it could not be used on cloudy days; one could send messages from west to east only in the mornings, and from east to west only in the afternoons; it was difficult to find men for lookouts who knew Morse code.1

1F. E. Powers

e) Carrier pigeons. There was an attempt made on the Idaho Forest to use carrier pigeons. This was not successful. Many birds disappeared and the smokechasers were accused of eating the birds since rations quite often ran short.1

1F. E. Powers

f) Radio was a great boon to Forest Service communication but there were many problems to solve. The first radios used, around 1928 or 1929, required a pack string to haul one, with tools and equipment to set it up.

In 1934 the Salmon Forest had the following radio set-up:

At Salmon — 1 M set used as a central control for the Forest radio network. When fire season is on will be hooked up continuously and operator on hand to receive calls from Salmon field stations.

Field Sectional Radio control stations having telephone into Salmon, and reporting by radio direct to Salmon: Stations reporting direct to sectional radio control stations: Lake Mountain — SF set Sal — PF set

Sheephorn — SP setLong Tom — M set Butt's Creek — SP set

Stoddard — PF setMiddle Fork Peak — SP set Sugar Loaf — PF set

(emergency point only)Three additional PF sets were placed with road and trail crews.1

1"Memo for RO Files," June 21, 1934, p. 4.

There were no portable two-way radios, so the Forest Service set up a shop and developed the SPF set. F. E. Powers recalls using one in 1937. It weighed 17 pounds but was very usable.

When World War II began, the Army did not have two-way radio, so they requisitioned the Forest Service radios until they could develop and produce their own. Improvements were developed rapidly, so each new issue of radio was vastly better than the last. Glenn Thompson recalls that during the war the Army always requisitioned the newest radios that the Forest Service had acquired.

3. Transportation

Trails were opened up as soon as possible after the establishment of the Forest. Some Indian trails or mining trails were improved and new trails were built as needed for fire protection. Through the years standards were developed for trails used for different purposes. By 1924 trails were usually referred to as primary trails, secondary trails, and way or fire-ways. Inspector C. N. Woods advised that "way trails" should be well blazed, with enough work done so a man could get through with a pack horse without difficulty. Ordinarily no dugout work was done on way trails; only cutting out of logs which horses could not readily step over, and standing timber removed to allow a horse through with an ordinary pack. Mr. Wood suggested that if no more than 35 horses used a route per year it could be classified as a way. More than 35 horses classified it as a trail, and maintenance should be done accordingly. A truck trail was a low standard road, nine feet wide and it usually followed along a ridge, going up and down with the ridge, with little effort to reduce the percent of grade. A six foot saw, an ax, and wedges were used in early trail work. Where possible, trail workers plowed with a horse and a two-way or reversible plow.

A 1924 report on trail work on the Salmon Forest includes the following:

—The Clear Creek trail and the Colson Creek trail were built in 1923.

—In 1923 a trail was built from the mouth of Camas Creek down the Middle Fork through the canyon to the Mormon ranch, the main object being to avoid the climb by the old trail over Aparejos Hill.

—The trail from Salmon City to Baldy Mountain could be improved by removal of rock; the steeper stretches run 25 to 35%.

—There are stretches on the China Springs — Taylor Mountain Trail that are 50% grade.

—A start had been made to cut out a trail between the Blackbird Lookout and the main Redrock — Cathedral Mountain — Divide trail. This section is a valuable protective trail.

—The old prospector's trail across Hoodoo and Lake Creeks and up Camp Creek is in places very steep, with 25 to 40% grade.

—The Middle Fork Peak guard has built a trail from his camp under the Middle Fork Peak saddle up to the saddle.

—There is a trail and a way, west from Middle Fork Peak to Mormon ranch on the Middle Fork via Warm Springs Creek. Dropping off the mountain the grade is from 30 to 50%. As much as 80 pounds of telephone wire has been packed by horses up this trail.

—A trail has been proposed down the Middle Fork below the Mormon ranch as far as the mouth of Big Creek, on the east side of the river. At present the trail is on the west side from the Mormon ranch to Snowshoe Johnson's cabin, fording there to the east side.

—There is a ford at Snowshoe Johnson's cabin across the Middle Fork and a trail down the east side two miles to Wilson Creek, up Wilson Creek and over to the Hoodoo meadows on Hoodoo Creek. There are several bridges across Wilson Creek which will soon be too rotten to use. These bridges need not be replaced since the trail is used only in summer when the creek can be forded. Vegetation since the Wilson Creek fire of 1929 has reclaimed the early trail and today travel down Wilson Creek is very difficult.

—There is a satisfactory trail between Leesburg and Haystack Mountain when the down timber is removed.

—The trail down Pine Creek is very poor, parts of it running from 25 to 40% grade and in places it is very brushy.

—The trail from Shoup down the Salmon River to Colson Creek is in good shape. Much rock work had been done on it since 1916.

—The trail and road from Horse Creek Hot Springs up Horse Creek to Blue Nose is good except for down timber.

—The trail from Blue Nose to Shoup via Horse Fly cabin is very good.

—The short cut trail from Indianola up Ulysses Mountain to the lookout is excessively steep, 30 to 40% in places.

—The trail up Ulysses Mountain to Grizzly Spring is acceptable.

—A satisfactory trail runs from Hughes Creek ranger station to the Stein Mountain Lookout. Some stretches are as steep as 35%.

The Timber Creek watershed has trails up most of the main forks. These trails should be maintained by blazing, and cutting out down timber.1

1C. N. Woods, "Salmon Inspection Report," August 20, 1924, pp. 9-21.

The trail grader was invented by John Raphael, later Supervisor of the Weiser Forest. It had an adjustable blade about 2-1/2 feet by 12 inches, pulled by a horse from a singletree. This was a common tool in trail-building. There is still a trail grader on the Salmon Forest (1970).1 Different types of trail graders in 1928 included the light weight Varner; medium weight Quillen and California; heavy weight D-1 and Beatty.2

1F. E. Powers.2C. N. Woods, "Salmon Inspection Report," August 29, 1928, p. 5.

High water made the Salmon River trail below Shoup impassable for three to six weeks each year. D. E. Romano in 1928 recommended a higher trail down the Salmon River, with a bridge across Owl Creek so the trail could be used throughout the year.3

3D. E. Romano, "District 1 Inspection," May 28, 1928, p. 4.

The sheep bridge across Panther Creek at the mouth of Dry Gulch had washed out in the flood of 1926, making it necessary for Forest Officers to go to the mouth of Garden Creek, during high water, in order to reach Sage Brush Lookout and Clear Creek. A new trail bridge was built across Hayden Creek in 1929 just below Tobias Creek. A sheep bridge was built in 1930 on Hayden Creek, just above the mouth of East Hayden Creek.

Melvin and Marion Mahoney were the trail crew in the Yellowjacket area in 1930. Frank Neal did the blasting.4 The Williams Creek Way and the Deep Creek Ridge Way were inspected by Kinney in 1930. These were fire ways, for travel by fire guards to fires by day or night. Other "ways" were the East Owl Creek Way, from the Owl Creek Park to the Bear Trap ridge; and the Pattee Creek — Meadows Way.

4J. N. Kinney, "Memorandum of Inspection," July 22, 1930, p. 5.

In 1931 there were trails maintained by smokechasers on Colson Creek, Skunk Camp Lookout Trail, Skunk Camp to Salmon River, which descended over 4000. feet in about 3-1/2 miles, and one being built up Horse Creek, where there was an old trapper's way that was slow and dangerous. There was a new trail on West Horse Creek with tread made by horse and trail plow.

The Shoup pack bridge, built in 1914 by Jack Bundy, was repaired in 1927 (south tower replaced) but by 1931 needed further repairs of new stirrups, stringers, and railing.5 By 1939 this bridge was unsafe and was so labeled.

5J. N. Kinney, "Inspection Report," October 7, 1931, p. 1.

By 1933 there was a pack bridge at the mouth of Big Creek on the Middle Fork; by 1934 a pack bridge at Brushy Creek.6

6Interview with Les Gutzman, Salmon, Idaho, October 23, 1969.

In 1939 the Clear Creek section of the Crag Ways was constructed by Arthur Ludwig, under Ranger A. R. McConkie, and a pack bridge was built across the Middle Fork at Crandall's ranch (Flying B).

Horses and Pack Animals. Trails were of great importance in the Forest for fire control, even after roads were built. Also importance in the area of fire control were the horses and pack animals which traveled the trails. When the Salmon Forest was established, each ranger was required to furnish his own saddle horse, and to pay the Forest Service annually for its feed. The Forest Service kept a few horses for use by inspecting officers and others. In 1916 there were eleven Government horses on the Salmon Forest.

Mrs. Jim Mahoney (Marian) remembers two Forest Service mules at Indianola in the late 1930's: old "Jimmy" and "Bobo." When the men were all away the women would have to put the mules and horses out to pasture and bring them in at night. Mrs. Clint Quesnel (Barbara) showed Sue Mahoney, who was just a child, how to hobble the bell-mare. Sue took care of the horses and mules without any trouble, which surprised the men. But the mules could jump fences and open gates. The corral fence was raised to about nine poles, but if "Jimmy" was left alone, he would still jump it.1

1Interview with Jim and Marian Mahoney, October 22, 1969.

The Forest Service has often hired professional packers and their packstrings for specific jobs, such as hauling building materials for a lookout or a pack bridge, or materials to and from fires. Wallace St. Clair was one of the earliest packers for the Forest. Other packers have been Frank Lantz, Earl Poyner, Elmer Phillips, and Horace Marsing.

In 1952 a safety training film "Horse Sense" was made on the Salmon Forest. Most of the filming was done around the mouth of the Middle Fork and in the Crags. The film showed the care and use of horses and mules, emphasizing trail and camping use; hobbles, bells, feed, etc. It was filmed for Forest Service, sponsored by the Department of Agriculture. The film won a National Safety Council award for program content and technique, and was released for television showing. Within a short time the primary users of the film were dude ranchers.

Roads. "Winter roads" were sometimes used in places where travel was difficult and the building of regular roads was not feasible. A winter road mentioned earlier was one over Lost Trail Pass around 1900. Snow in the winter covered the boulders and smoothed the way, making it possible to travel with horses and sleighs. Winter roads were used by loggers in areas where it was difficult to build roads. A winter road was used in Pollard Creek by loggers in 1923.2 In 1928 Forest Service Inspector U. S. Swartz recommended a winter road be built by Bolts and Oltmer between their mill and the timber up Hayden Creek, where slide rock and solid rock made ordinary road building impractical.1

2C. B. Morse, "Inspection Report," August 8, 1923, p. 1.

1U. S. Swartz, Logging Engineer, "Inspection Report," 1928, p. 2.

Rich Knoblock describes the "winter road" procedure which was a common practice in the Salmon country in the early 1930's. They put one end of the logs on a sled; the logs and sled made the road in the heavy snow. Increased use and more snow and freezing improved the road. You could go around a fairly steep slope even where there was no road. Knoblock used this method on Kadletz Creek.2 Another name for the winter road was a snow road.

2Interview with Rich Knoblock, Boise, Idaho, February, 1971.

The first roads in the Salmon Forest were improved wagon roads. In 1928 Inspector C. N. Woods rode the Government Dodge truck from Prairie Basin to Yellowjacket Ranger Station and back, and then to Meyers Cove and back to find out if in case of fire, men and supplies could be transported by truck. He found it satisfactory, needing some maintenance on high centers.3 In 1930 Supervisor Kinney found the nine miles of road from Leacock's ranch (mouth of Napias Creek) to Leesburg barely passable to Ford cars because of high centers. Other cars with lower clearance could not make it.4

3C. N. Woods, "Salmon Inspection Report," August 29, 1928, p. 6.

4J. N. Kinney, "Inspection," July 22, 1930, p. 1.

In 1931 work was begun on the Spring Creek motorway and the Williams Creek road. Roads in the Forest were still being graded with horse-drawn graders. Power enthusiasts recommended going entirely to mechanized equipment, while others favored continued use of teams of horses on the roads, partly so they would be ready for use on fires, to pull fire plows.5

5J. N. Kinney, "Letter to Regional Forester," November 18, 1931, pp. 5-6.

Though there was a wagon road to Leesburg and Forney, the only auto route in 1932 was up the Salmon River and over Morgan Creek. The road over Williams Creek was not finished. Down Panther Creek below Napias Creek there was only a pack trail.6

6Interview with Lester and Mildred Gutzman, Salmon, Idaho, October 23, 1969.

In the 1930's many miles of road were built on the Salmon Forest. Men from the CCC camps built the road down the Salmon River below Shoup to the Middle Fork, finished the road over Williams Creek summit, built the road up Panther Creek from the Salmon River, the Spring Creek road and others. By 1939 the Salmon National Forest had a total of 404 miles of existing truck trails, exceeded in mileage only by the Boise and Targhee National Forests in Region Four. Much of this was very low standard ridge road, such as the Spring Creek Motorway System. Williams Creek road was considered a medium service truck trail and probably the most important single road on the Forest. In 1939 a spike camp from the CCC Camp on Cove Creek was doing betterment work on the Panther Creek road, between Forney and the Salmon River, under superintendent Herb St. Clair and his foreman.1 Road projects in 1943 included Silver Creek, and a crew worked on the Nicholia road under Herb St. Clair.

1A. L. Anderson, "Inspection Report," September 28, 1939.

Improved engineering methods, better equipment and vehicles have changed the work of road construction in recent years. Many roads have been reconstructed to meet present day needs for administration for public use, new standards of drainage and land use.

Forest Service Bridges. The Shoup Pack Bridge was built in 1914 by Jack Bundy. It was repaired in 1927 and 1931, condemned about 1939, and has since been destroyed. Horse Creek Pack Bridge was built in 1934. It was condemned and destroyed early in 1971. Stoddard Pack Bridge, at the mouth of the Middle Fork, was built by the CCC men in 1937.

Big Creek Pack Bridge was first built in 1933. It was rebuilt in 1957. Bernard Pack Bridge was built at Brush Creek in 1934, rebuilt in 1957.

There are pack bridges across Camas Creek at the mouth of Yellowjacket Creek, across Yellowjacket at Buck Creek, and across Panther Creek at Woodtick Creek.

The Salmon River auto bridges at Pine Creek and Cove Creek were built during the 1930's by the CCC men in the process of extending the Salmon River road below Shoup to the Middle Fork. Neal Poynor relates that they walked a "cat" across the river at Shoup in the winter of 1933, and took a compressor over by boat, to work on the bridge and the road below. The Pine Creek bridge was completed in the spring of 1934.

The three Salmon River auto bridges above Salmon, called the Shoup bridge, Rattlesnake bridge and Iron Creek bridge, were built originally by the county, since there were ranches on the other side, but the roads all entered National Forest Land.

Landing Fields. There are three landing fields in the Salmon Forest. One is a private field on the Flying B ranch. The Forest Service Bernard Landing strip was built in 1932. Wayne O'Connor and Dutch Morrison worked on it, taking in a plow, scraper and fresno by pack string. The Forest Service emergency landing field at Hoodoo Meadows was begun by the CCC's in 1935, and completed in 1937. An airstrip was cleared but grading not completed south of Butts Point. The slips used in grading are still on the site.

Helipads. Since the advent of the use of helicopters on the Forest, helipads have been built in various places to facilitate the work of the helicopters. Many helipads are now marked so they can be seen from the air, and are shown on maps of the area. There are over 200 helipads on the Salmon Forest.

4. Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps came into being during the depression of the 1930's when hundreds of thousands of people were without work. A New Deal plan of D. F. Roosevelt, it became a program of self-sustaining public work. Most of the camps worked on projects in national, state, or private forests. CCC boys planted trees, fought forest fires, built roads and trails, thinned overcrowded timber stands, fought diseases of the forest such as bark beetles, gypsy moth, and pine blister rust. They re-seeded thousands of acres of grazing lands within western National Forests, and built recreational facilities still in use in many forests. The CCC program lasted from 1933 until 1942. 2,500,000 young Americans took part in it. At its peak between 1935 and 1937 there were 1500 camps with a top enrollment of 500,000.1

1Orville Freeman, Secretary of Agriculture and Michael Frome, The National Forests of America (New York: G. P. Putman's Sons. In association with Country Beautiful Foundation, Inc., Waukesha, Wisconsin, 1968), pp. 88-90.

The camp activities of the enrollees were supervised by military personnel, while the field activities were supervised by civilians hired and directed by the agency responsible for the work.

There were four CCC Camps in the Salmon Forest, with another CCC Camp on Haynes Creek under the Department of Grazing, a department dealing with non-forest public land. Those on the Salmon Forest were F-92 at Squaw Creek with Emmett Steeples, Superintendent; F-103 at Shoup; F-176 at the mouth of Panther Creek with Frank B. Bradley, Superintendent; and F-401 at Ebenezer Bar with Herbert St. Clair, Superintendent. About 200 men at a time were sent to each camp, plus their Army officers. They worked under direction of the district rangers on various projects in the Salmon Forest.

Remembered most by the public was their work in building roads and recreational facilities. The CCC work extended the road from Shoup down the rugged Salmon River canyon to the Middle Fork, finished the road over Williams Creek summit, built the road up Panther Creek from the Salmon River, the Spring Creek road, and Anderson Mountain road along the Continental Divide. Recreational facilities included building the original facilities at Twin Creek, Cougar Point, Long Tom, Deep Creek, and Wagonhammer Spring. In addition they built telephone lines, bridges, a landing field, maintained roads and trails, and fought fire when needed. In the period from June 1, 1933 to January 1, 1936, they spent 11,054 man days fighting fire.

The boys came from all over the United States. Some were from southern Idaho. Retired District Ranger Neale Poynor remembers that some of the boys from New York had never walked on ground except in a city park. Others with rural background could not write their names. The minimum age for the CCC program was 18 years, but there were older men also, who had wives and children left at home. The boys were not frightened or hostile, but were inexperienced, and in strange surroundings, and some did not know how to take care of themselves. Most of them were willing to learn, and anxious to do well. The CCC program gave them a chance to earn something on their own, and have a place to live. Many continued their schooling in night classes held in the camps. Neale and Laura Poynor recall attending an eighth grade graduation exercise held at one camp.1 The construction for the Salmon Forest was something the CCC men could be proud of and they acquired worthwhile skills and a love of the country in which they had worked. Some CCC men remained in the Salmon River area. Forest Service personnel and local citizens voiced approval of their work and of the CCC program.

1Interview with Neale and Laura Poynor, Boise, Idaho, November 18, 1969.

One CCC project was construction of an emergency landing field on Hoodoo Meadows, to be used by planes on fire control work over the Primitive Area. In 1929 this meadow had been used as a base camp on the Wilson Creek fire. A 25 man CCC crew began work there in July 1935. The altitude is 9000 feet. Water froze every night. A PF radio set was used for communication. They were unable to finish the field that summer because work was interrupted by three different fire calls. One fire call was to the Big Horn Crags on Roaring Creek. There was no trail and the boys had to back pack their groceries and fire fighting tools. Leaving a 1 o'clock in the afternoon, they reached the fire at 2 a.m. the next morning. On one fire, one CCC boy was left at the Hoodoo Meadows camp to guard the supplies. When a Forestry foreman arrived at camp in the middle of the night he found the boy sitting in the midst of the food supplies with a meat cleaver in one hand and a double bitted ax at his side, for defense purposes.2 The Hoodoo Meadows Landing Field was completed during the summer of 1937.

2"Hoodoo Meadows Landing Field," CCC Information Report, February 18, 1936.

The Salmon Forest still had three CCC camps in 1937. There was only one camp operating during the summer of 1939, F-401, and two the following winter.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

history/part2.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |