|

Public Camp Manual

|

|

NATURE AND ORDER OF IMPROVEMENTS

II. ROADS AND PARKING SPURS

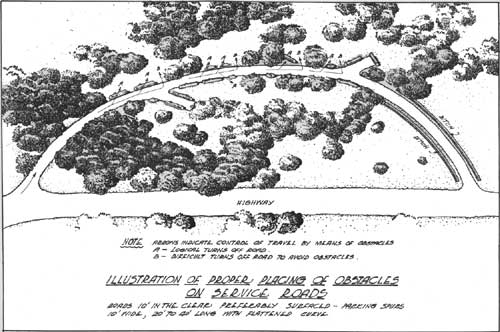

Unregulated travel by automobiles constitutes the greatest source of damage to campgrounds. For that reason the planning of a road system should follow closely upon clearing and fireproofing. In laying out camp roads, special attention should be given to the suggestions in Dr. Meinecke's bulletins.

In order to protect the vegetation, it is absolutely necessary to control the automobile traffic. Indiscriminate driving about our camps has resulted in scarring, breaking off, knocking down and otherwise injuring shrubbery, young trees, and ground cover generally. It has become of primary importance that automobiles be restricted to roads and parking spaces. Many methods of achieving this result have been suggested, raging from the mere grading and surfacing of roads and parking spaces to the use of iron posts set in concrete and having chains hung between them. Some of the methods suggested will be discussed briefly.

Use of Obstacles

Rocks: On the surface, it would appear that traffic could best be controlled by means of large rocks, so placed as to keep vehicles within the desired routes of travel. This method, however, is far from simple in its application. The general tendency is to use rock for rock's sake, which results in a purely artificial appearance. Rocks, to be effective, must be large enough to be almost immovable, which requires the use of equipment in placing them. They do not fit in areas such as timbered flats, where there are few native rocks on the surface, whereas they do appear more natural in rocky canyon bottoms.

Ditches: In some places, ditches along the road will serve to restrict promiscuous motor traffic. However, sloughing from the sides may gradually fill the ditches, so that frequent maintenance may be necessary. The ditches, too, if made sufficiently obvious to the motorist, are apt to look unnatural.

Posts: Some of our camps will be obviously artificial as a result of intense development necessitated by heavy use. In such cases it may be desirable to install posts, where required, as barriers. Since posts have an artificial appearance, it is only in rare instances that such a method of control would be justified.

Fences: While there are occasions when the construction of fences is necessary, they are as a rule more objectionable than posts, from the aesthetic standpoint.

Large Logs: In timbered areas, large logs may be used with success. They will undoubtedly stop cars, and help preserve the natural conditions. They are, however, difficult to move into place, and may eventually be chopped and hacked in such a way as to spoil their appearance.

Low Barriers: Wherever timber is available, a very attractive yet unobtrusive barrier may be constructed by setting posts two feet in the ground, leaving one foot exposed. To these posts, rails of 6-8 inches diameter may be bolted or fastened on with strap iron. Such barriers should not be continuous, but should be placed only where it is necessary to provide protection to the vegetation. Shrubs could be planted behind the barriers, and would eventually screen the entire railing. In addition, some natural seeding and growth may be expected in the protected zone below and just behind the barrier. This type of obstruction is recommended for all timber-type camps, where the material is available.

Grading and Surfacing: This is by far the simplest method of traffic control. It differs from all other methods in that no obstacles are constructed, the entire plan being based on simplicity. Merely grade the roads and parking spaces, and surface with some material which will contrast with the surrounding ground area, such as light gravel. The travel routes will then be sufficiently well-defined to the general public. This scheme may not work in the majority of cases. At any rate, it has the advantage of later modification to one of the other methods without sacrifice of work already done. In any case, full advantage should be taken of trees, brush, rocks in place, or other natural barriers, an attempt being made to fit the roads to local conditions in such a way as to require the least possible amount of obstacle construction.

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

General Construction of Roads

One-way roads will be constructed in most camps. These should be 10-feet wide, clear of all obstructions. The parking spurs should also be 10-feet wide and 20-feet long on the short side. It may be advisable to construct an occasional spur of greater length, say 40-feet, to allow for cars with trailer attached. Dr. Meinecke dwells on this subject in detail in his bulletins, which should be consulted.

Traffic routes and parking areas should be oiled in heavily-used camps, where dust becomes a problem during the summer.

House Trailers

During recent years, a de luxe type of auto trailer has been developed, which is literally a house on wheels. Some of these trailers are 30-feet long, painted in gaudy colors, and are self-contained units. The people who travel with these trailers are not campers. They carry their own stoves, water supply, toilet facilities, and lighting systems. The trailer has built-in bunks and table, so no tent or camp table are required. In fact, they are prepared to atop wherever night overtakes them.

These trailers should not be allowed on Forest Service camps, which have been designed and developed for bonafide campers and picnickers.

Since the travellers with this equipment have no need for most of the camping facilities provided by the Forest Service, they should be directed to park and set up housekeeping at especially selected spots where they will not conflict with the administration and use of the areas devoted to bonafide camping. Sections set aside for use by house trailers should be provided with toilet facilities, garbage collection, and water.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/5/public-camp-manual/sec4-2.htm Last Updated: 11-Jan-2010 |