|

History of the Rogue River National Forest Volume 1 — 1893-1932 |

|

PART I

THE CASCADE RANGE FOREST RESERVE

HISTORY

of

ROGUE RIVER NATIONAL FOREST

OREGON

Located

in

Jackson, Josephine, Klamath, & Douglas Counties, Oregon Siskiyou

County, California

January

1960

Compiled by

Carroll E. Brown

Forest Supervisor

THE CASCADE RANGE FOREST RESERVE

(Copied from Will G. Steel's scrapbook)

In October, 1885, I was in Salem, getting signature. to a petition for the creation of Crater Lake National Park. Returning to Portland I met Judge John B. Waldo who asked me why I did not apply for the entire Cascade range. Taking it as irony, I made a factitious reply. He assured me he was in dead earnest and asked me to call at his office, which I did. We talked the matter over at considerable length and I was deeply impressed with his knowledge of the situation and the value of such a move. Among other points he explained that two sections in every township of land in the mountains were known as school land, all the best of which had already fallen into private hands. The remainder was of little or no value; but if the government withdrew from the market the entire range, lieu land would be granted for all school sections so withdrawn, which would then be selected from the best government land within the State, and of course would be salable and should add at least $1,000,000 to the school fund. In addition to this, if withdrawn by the government, such move would be followed by appropriate legislation for patrolling and protecting the forests against fire, which would not last long in their then unprotected condition. The proposition appealed to me, especially when the Judge volunteered his legal services for the period of conflict. He prepared a petition which I circulated throughout the State, getting many signatures. Some of the signers, however, subsequently fought us bitterly. He was a member of the legislature and got a memorial through that body, which assisted us materially. The papers finally were sent to Washington, and we were informed there was no law under which the desired end could be attained.

In the meantime forest protection was being agitated by the American Forestry Association, public sentiment was being awakened and Congress was prevailed upon to act, by attaching the following section to one of the great supply bills, which was approved by the President, March 3, 1891:

"That the President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve, in any state or territory having public lands, wholly or in part covered with timber, or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not, as public reservations, and the President shall, by public proclamation, declare the establishment of such reservation, and the limits thereof."

Practically all agitation and legislation by congress was brought about by the Forestry Association. B. E. Fernow was chairman of the Executive Committee and was apparently a majority of the organization, ably assisted by Edward Bowers, an active minority. It was a capital institution, located in the political center of the country. On diverse and sundry occasions, important business was transacted, to the entire satisfaction of the enthusiastic audience, of which I was 100%.

Soon after the foregoing article became law, our work was renewed with vigor. A great deal of preliminary work had been accomplished, when the matter was brought to the attention of the Oregon Alpine Club, and thereafter pretty much everything was done through that organization. There were many delays that seemed to us wholly unnecessary, so that matters dragged along until an exciting presidential campaign was upon us. Soon after election I went to Washington to look the ground over and found Fernow and Bowers on guard and wide awake to the situation. While there I was brought into close relations with Secretary Noble of the Interior Department, whom I found deeply interested; but Cleveland had just been elected, and consequently the Harrison administration objected to issuing the proclamation. During one of our interviews, Mr. Noble laid a common land office map of Oregon on the table and "handing me a blue pencil, asked me to mark upon it just what I wanted. I told him I had paid $25 to have a special map made, after a great deal of study, and it should be in his office. However, he wanted it for his own use and information, so I drew as carefully as I could the desired boundaries of the reservation. Subsequently I was informed that the map of the blue lines was used instead of the large one in preparing the President's proclamation. Considering the care and study Waldo and I gave the matter when preparing the original map, I doubt there being any material difference between them.

Long before Cleveland became president he was deeply interested in forest protection, and was probably one of the best informed men on the subject in the country. He became president March 4, 1893, and immediately appointed Hoke Smith Secretary of the Interior. Whether Smith was interested because of the President's views, or on his own account, I do not know, but he was greatly interested in the matter and was always our friend. Our petition was carefully considered and on September 28, 1893, the President's proclamation was issued, creating the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, extending from the Columbia river to within 22 miles of California, a distance of about 250 miles and containing approximately 4,500,000 acres.

As soon as the legislature met I wrote to Governor Lord, explaining conditions and suggesting a message be sent to that body, recommending an increase in the price of school lands, supposing $5 per acre would be established as a minimum. He took action at once and the minimum was fixed at $2.50 per acre. There was an immediate scramble of land thieves for lieu bases, before the State could act, and thousands of acres thus were practically lost to the school fund.

Soon after the President's proclamation was issued, opponents of the measure began to organize and show signs of a strong and systematic fight. Opposition centered in sheep men of Eastern Oregon, who had always had free pasture for their flocks; and they bitterly resented what seemed to them an unwarranted interference with their rights. Previous to this there had been no sort of effort put forth to control forest fires which, when started, were permitted to burn until they ran out of material, or early autumn rains extinguished them. As a result, summer and early fall, Western Oregon was filled with a dense pall of smoke so thick at times as to affect one's eyes. Millions of feet of the best timber in the world were annually destroyed, with no effort to save it, so that in a few years there would be none left for commercial purposes. It was openly charged many of these fires were set by sheep herders with consent of the owners, that more pasture might be had for their sheep. Sharp hooves of great numbers of sheep totally destroyed light vegetation such as grass, flowers, and small brush, thus leaving the ground totally barren. It was then forsaken by the flocks and new pastures sought. John Muir termed sheep "hoofed locusts" and it was justly so.

An aggressive organization of sheep men was perfected and notices given to the Oregon delegation in Congress that every member was expected to fight the Cascade reserve to a finish and have the lands composing it restored to the market. Unless such action was taken at once, sheep men would fight them at the polls, and do everything possible to defeat them for re-election. Members of the delegation immediately loved the sheep men from the depths of their great hearts, and manifested a disposition to take their orders, regardless of the best interests of the State. Here was a great political organization with money, votes, axes to grind, and what more do you want? All they asked was that the delegation represent their interests, which they were willing to do, so there you are. Sheepmen soon heard the voices of their minions in the halls of Congress, shouting of their downtrodden rights and demanding satisfaction at government expense. Senator Mitchell was acknowledged their leader and made more noise than anybody. He would do this and he would do that - and they believed him, for was he not invulnerable?

I had always been an enthusiastic Mitchell man; and once my brother, his manager, pulled through a doubtful election, when everybody else had given up. I felt strongly attached to him, so called upon him immediately after arriving in Washington. I was paying my own expenses and it was a heavy tax, so I asked for and was given employment at the munificent salary of $10 per week and remained with him for a month. In the meantime I gradually discovered there was a very deep chasm between us. It was wide and yawning, although not bloody...not yet, but it looked threatening. He finally told me, when my work was finished, that a proclamation was then prepared to "wipe the Cascade reserve off the map," and would be signed by the President before the close of the week. Next morning I called upon Bowers who confirmed the statement, adding that Mitchell had interceded with the President and stated in most positive terms that the people of Oregon were unanimous in demanding that lands within the reserve be restored to the market. There was no division of sentiment whatever, and indignation was simply unbounded. I denied the statement and asked time to prove my assertions. Bowers quickly got in touch with the White House, then suggested I call upon S. W. Lamoreux, Commissioner of the General Land Office, and a bosom friend of Mitchell, and ask for 30 days' delay.

As early next morning as conditions would permit, I called at Lamoreux's office and sent in my card. He was busy, so I waited. After awhile the clerk told me he probably would be busy a long time. I thanked him and said I would wait a long time. Again he came and told me flatly I could not see him. "Did he say so?" I asked. The clerk returned an evasive answer, so I told him that was satisfactory to me, provided Mr. Lamoreux would say it. I had my own ideas as to what would happen, and soon imagined the Commissioner had the same idea in his noodle, for I was immediately invited into his presence. I found a large man, physically, who seemed impressed with his own importance and vast dignity and the utter insignificance of other people, which I failed to appreciate, so greeted him pleasantly and was met with, "Well, what do you want?" I stated my case and asked for a delay of 30 days, that I might show the President wherein Mitchell had deceived him. He refused and I started for the door. He followed me and suddenly seemed anxious to talk, but I wanted to escape. He contended that the time was unreasonably long, to which I responsed, "I have your answer, Mr. Lamoreux." However, before I could get away he granted the 30 days. I immediately reported to Bowers, who seemed to enjoy my report. I hired a typewriter and spent my time sending telegrams and letters to Oregon.

Bowers had informed me that the President would appreciate a legal opinion on the situation, by some attorney fully informed on the subject, so I carefully prepared a letter to Judge Waldo, giving details as fully as possible, and asked him to prepare such a document which he began immediately. Judge C. B. Bellinger was then on the federal bench in Portland and was working heartily with us, so Waldo conferred with him while working on the brief and when finished they went over it together. Waldo suggested it would have a better effect if Bellinger would sign and forward it, which he did. It was an unusually strong document and the President was greatly pleased with it and sent Bellinger a long autograph letter of commendation.

In about a week I again called on Bowers, who informed me the President had received a large number of telegrams from Oregon, protesting Mitchell's statements, and he had come to believe the Senator had lied to him. I had previously gone to the business office of the Commissioner and asked to see certain papers I knew to be on file there, but was flatly refused by a man who seemed to be in authority. Bowers suggested I go back and present my request to the same official, which I did. He was very busy and sent a clerk to me, but I insisted on dealing with the man in charge who finally came; and I asked to see the papers, which were at once shown me. I examined them carefully and made notes although I then had no use for them, and at once reported to Bowers who chuckled to himself, just as though it were fun. At this point it was thought a little publicity would help, so a meeting of the American Forestry Association was called and certain resolutions passed, given to the Associated Press, and next morning appeared all over the country.

Mitchell omitted no opportunity to strike at the reserve and was industriously working up a sentiment against the reserve principle, especially in Congress, and above all was trying to embarrass Cleveland. The matter assumed national importance and became a bone of contention in officialdom, and for a time it looked as though all laws for the protection of forests would be repealed. The President was harrassed by contending parties and no one could foretell the end. At this juncture Fernow thought out a plan that proved a turning point in our favor. He suggested to the President that the matter be referred to the National Academy of Science, with a request to make an investigation and report, supposing the work would be done in Washington. Hoke Smith immediately asked the Academy to appoint a committee to recommend a feasible and comprehensive forest policy, together with an expression on the following points:

1. Is it desirable and practical to preserve from fire and to maintain permanently as forest lands those portions of the public domain now bearing woodgrowth for the supply of timber?

2. How far does the influences of forests upon climatic soil and water conditions make desirable a policy of forest conservation in regions where the public domain is principally situated?

3. What specific legislation should be enacted to remedy the evils now confessedly existing?

In reply, the President, Mr. Wolcott Gibbs, said the inquiry should consider these points:

First, the question of the ultimate ownership of the forests now belonging to the government; i.e., what portion of the forest on the public domain shall be allowed to pass, either in part or entirely, from the government control into private hands?

Second, how shall the government forests be administered so that the inhabitants of adjacent regions may draw their necessary forest supplies from them without affecting their permanency?

Third, what provision is possible and necessary to secure for the government a continuous, intelligent, and honest management of the forests of the public domain, including those in the reservations already made, or which may be made in the future?

The following committee was then appointed to make the investigation and report:

Charles S. Sargent, Professor of Arboriculture at Harvard University and Director of the Arnold Arboretum, Chairman.

Gifford Pinchot, consulting forester, Secretary.

Alexander Agassiz, Curator of Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

General Henry L. Abbott, late Chief Engineer, U. S. Army.

Professor William H. Brewer, of Yale University.

Dr. Arnold Hague, U. S. Geological Survey.

John Muir joined the commission in the field.

As soon as matters had reached this point the academy replied that it did not know enough to give advice, and that it would be necessary to appropriate $25,000 for expenses of travel. A real nice trip, with all expenses paid.

Late in August, 1896, the Mazamas visited Crater take and I accompanied them. While in Ashland I received a telegram from the Commission asking me to return to Portland and accompany them to Crater Lake. I continued with the club until we got to the Lake; then at six o'clock Friday morning left for Medford, 85 miles distant, walking the entire distance and arriving in time to catch the north-bound five o'clock train Saturday. I arrived in Portland Sunday morning, where I conferred with the Commission; then we returned to Ashland, where I fitted out, and we went to Crater Lake over the Dead Indian road. Some weeks were devoted to field work by the Committee, after which instead of recommending that the Cascade Range Forest Reserve be restored to the market, or to reduce the size, 13 new reservations were recommended, and Cleveland threw the gauntlet at the feet of Mitchell and his friends by creating all of them.

Mitchell, seeing the President was thoroughly in earnest in defense of the Cascade Reserve, and that his own fight was apt to be a losing one, devised a plan for three reserves; one to contain 322,000 acres in the vicinity of and surrounding Mount Hood, to be known as Mount Hood Public Reservation; a second in the vicinity of and surrounding Crater Lake, to be known as Crater Lake Reservation and to contain 936,000 acres; and a third in the vicinity of and surrounding Mount Jefferson, to be known as Mount Jefferson Reservation and to contain 30,000 acres; thus restoring to the market 3,320,000 acres. Of course Lamoreux supported the measure and strongly advocated it, by which means he came under suspicion by the President and was subsequently removed. Mitchell had the Republican State Convention place a resolution in its platform demanding the creation of these three reserves, in lieu of the Cascade reserve. A committee of sheepmen was sent to Portland, who gave out that unless the business men of that city supported them, they should boycott them; consequently practically all of them signed their petition and the Chamber of Commerce actively supported them. I was in Washington, where I promptly received a copy of the petition to which I prepared an answer, covering the ground as best I could. Subsequently it both pleased and amused me to learn that when the petition arrived it was placed on Hoke Smith's desk among many other papers; but my answer was shown him, which he carefully read, then the petition was examined and promptly rejected.

When the scheme failed, Mitchell became desperate and determined to resort to legislation, in which he had unbounded confidence. One day a gentleman called where I was rooming and asked for a private interview. After satisfying himself as to my identity, he informed me that he came from the White House with a message. Mitchell had gone to New York, but before leaving had prepared a resolution which was left with the chairman of an important committee with instructions to add it to a bill then under consideration, the object of which was to totally wipe out the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. It was desired that I go at once to the Capitol, where the committee was in session, see the chairman and tell him that if Mitchell's article was attached to the bill the President would veto it, then to ask that he call up the White House for confirmation, all of which I did. When Mitchell returned from New York the bill had passed the Senate, but his little thunderbolt was lost in the storm. (Thus, the Cascade Range Forest Reserve was saved. CEB)

CASCADE RESERVE

(A letter from Mr. W. G. Steel, in which he explains plans of protecting forests of the range)

Government Camp

Mount Hood

Nov. 16 To the Editor:

About four years ago I started a movement looking to the formation of a National Park along the summit of the Cascade range. Owing to the nature of the difficulties in the way the matter was abandoned. In March, 1891, a law came into existence under which the President was empowered to establish forest reservations. Nothing more was done until about two years ago when the Oregonian began agitating the subject. In the following April the matter was taken up by the Oregon Alpine Club, and a committee appointed to take such steps as might be necessary, and circulated a petition. The matter was favorably considered by officials in Washington, and the papers were ready for President Harrison's signature when the discovery was made that there was a big job somewhere and we were being used as innocent tools to carry it through. Telegrams were immediately forwarded to hold the matter in abeyance until an investigation could be had. This is the opposition recently referred to as coming to Oregon.

Through a liberal disposition to build up and maintain public schools, the general government gives to the State every section numbered 16 and 36 for school purposes. If for any reason the government withdraws this land from the market and any of the sections named are not received, the State is then entitled to select an equal amount from any public lands. Such are called lieu lands. Within the then proposed reservation there were about 250,000 acres of school lands, worth very little, on the general average. However, the moment this land is withdrawn from the market, the State can choose the best government land within its borders in lieu thereof. As I understand it, school lands are now sold at $2 per acre.

A SYNDICATE FORMED

Previous to this time, a gigantic syndicate had been formed, the object of which was to secure the withdrawal of the Cascade range, then buy from Oregon the best timber available, as lieu lands. In this way the school fund would receive $2 for lands worth, say, $5 per acre. This difference would go to line the pockets of the schemers.

After sending the telegrams above referred to to Washington, the papers were held until I arrived there last January, at which time Mr. Herman and I held a conference with Secretary Noble, and the whole subject was gone over carefully. It was then agreed that I should return to Oregon immediately, and if possible, get a law passed by the legislature to dispose of school lands to the highest bidder, or in some other equally good way. I left Washington at once, but was taken sick and delayed in Chicago, arriving at Salem only in the closing hours of the session, too late to get any sort of law passed. Under the circumstances I got a joint memorial through, and forwarded a petition asking that the entire range be not reserved but only a tract about Mount Hood and an extension of that already withdrawn at Crater Lake. At the same time a point was made of the fact that we wanted the entire range just as soon as necessary steps could be taken to protect mining interests and schemes of the timber syndicate could be frustrated. Mr. Herman succeeded in protecting the mines, while Governor Pennoyer gave me a letter stating that he had suspended the selection of lieu lands. As soon as this was accomplished every obstacle was removed, and President Cleveland signed the proclamation September 28.

FLANK MOVEMENT DISCOVERED

It seems our friends, the enemy, are not at all disheartened, but are trying a flank movement in the shape of the McRae Bill, which is nothing more or less than the thinnest possible disguise for the jobbiest kind of a job. However, Mr. Herman thoroughly understands the situation and will fight this new dodge to the bitter end. The bill is drawn for and is supported entirely by the same timber sharks we have so recently defeated, and should be shown up thoroughly by the press of the State. A word from the Chamber of Commerce would also have a good effect. Do not be deceived by the supposition that this is merely a local syndicate, for it is backed by some of the ablest men in the country, both mentally and financially, who understand, however, that their plans will fail if the public thoroughly understand them.

Surveyor General Byars is quoted as opposing the reservation, because a sawmill ran for 40 years and yet the ground was covered with a young growth. Mr. Byars is a very fine gentleman but he does not seem to know much about the intent and scope of a forest reservation. Dr. M. M. Chipmad says in his paper on Government Forest Reservations, read before the medical society of the State of California, at its annual meeting held in San Francisco, in April, 1893: "The first step in the process of denudation of trees, is cutting and taking away of valuable parts of the timber, leaving tops of trees, chips, and useless parts upon the ground which, after becoming dry, burn rapidly and fiercely whenever, by the carelessness of some hunter or camper, fire gets started and sweeping fire destroys the life of the undergrowth. After the next rain following the fire, vegetation starts up and among it numerous seedling trees, in Nature's attempt at reforestation. But with the spring season great flocks of sheep are driven upon the recently burned-over lands, which not only eat the herbage but also nip off close to the ground and destroy the seedling trees and the sharp hooves of the sheep tramp the ground until it becomes very compact on the surface; and after a few seasons of that kind of treatment the soil becomes packed too hard for seeds to germinate in it, or for the winter rains to penetrate.

HOW FORESTS HOLD RAIN

In the primeval forest the rain, as it falls, is held back from running off by leaves and branches which cover the ground, and the soil, free from the tramping of flocks or herds and covered by decaying vegetation, remains soft and permeable, and thus the water penetrates deep into the ground, to percolate off slowly to the lower levels, where its presence during the dry season fructifies the earth and sustains the growing vegetation until harvest. But when the forest has been removed, vegetation destroyed and the soil packed hard, the falling rain, instead of being absorbed, runs off as fast as it falls and the full ravines and swollen streams, emptying their contents into larger channels fill them to overflowing, and the increased body of water spreads out over bottom lands, doing damage to farms and towns in its course, and then hurries off to the ocean.

Every summer thousands of acres of forest are destroyed by fire alone in Oregon, that will require generations to again cover the ground. Especially is this true along the summit of the Cascades, where timber grows very slowly. Here at Government Camp we have trees over 100 years of age that are less than 12 inches in diameter. Today I counted 150 rings in a white fir stump of that size. Again, the soil over a large portion of the high altitudes of this range is composed entirely of a vegetable mold, that smoulder and burns out entirely during a forest fire, leaving the ground not only without vegetation, but actually without a soil to maintain it.

It is not the purpose of the general government to let the matter rest, after withdrawing this vast scope of country from the market. Not by any means. In fact the work has just commenced, and this is only the first step. It is now in order to protect the actual settler, and the mines, as well as the forest. To provide for policing the reservation and punishing anyone disposed to set out fires or play vandal in any manner. To make a careful examination and restore to the market any lands that may be found to be strictly agricultural, and to correct any mistakes that may have been made.

— Oregonian, November 25, 1893

The preceding pages relate the resentment that followed establishment of the first forest reserves in the West. The stockmen were accustomed to using the Public Domain as "the first one there gets the choice feed" for their livestock. Large timber companies from the East hired timber cruisers to locate claims under the "Timber and Stone Act of 1878". Fraudulent land claims were common practice. It was only natural that people resented the locking up of the vast area of the Public Domain through creation of the forest reaerves.

A history of the Rogue River National Forest would not be complete without giving recognition to those few individuals who aspired to guard the reserves from fire and depredations under the General Land Office.

Few if any records are available on the early day organization or any aspect of their work. The newspapers were the only source of information that could be found which would give some accounts of the early day rangers and their work.

It is evident when reviewing the following items that local people appreciated the work of the rangers, as wild fires were common. Several accounts mention the "smoke-filled atmosphere" and give much credit to the able leadership of Hon. Nat Langell, the first supervisor, and his small band of rangers in controlling these fires.

It was not easy to manage these newly established reserves. The patrol areas of the rangers were large, equipment was lacking, but their courage and determination were dominant. They pioneered a movement that grew into the present organization of the Forest Service under the U. S. Department of Agriculture. Due to the controversy over the fate of the first forest reserves, including the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, and to lack of authority, the Department of Interior had no organization to administer these reserves.

As Steel mentions above, the National Academy of Sciences was asked to recommend a national forest policy. The Forest Commission, established by the National Academy of Sciences, studied the western reserves already established and other potential areas. They recommended the creation of thirteen additional forest reserves and a plan for administration of all reserves. A stormy battle ensued, both in Congress and by the so-called enemies of the reserve movement, when President Cleveland proclaimed on February 22, 1897, ten days before going out of office, the creation of these thirteen reserves. Gifford Pinchot spearheaded the drive in Congress, to get necessary legislation enacted to save the reserves and administer them in a businesslike manner. It was finally resolved with the enactment of the Act of June 4, 1897 This Act still is the most important Federal forest legislation ever enacted. It did two essential things: It opened the forest reserves to use; and it cleared the road to sound administration, including the practice of forestry. It provided that the surveying, mapping, and general classification should be done by the U. S. Geological Survey, and the execution of administrative work by the General Land Office. (1)

(1) Page 116, Breaking New Ground — Gifford Pinchot

There were three forest reserves in Oregon at this time, namely:

Bull Run Timber Land Reserve — In Multnomah, Wasco and Clackamas Counties. Proclaimed June 17, 1892. Area 142,080 acres.

Cascade Ranger Forest Reserve — In Multnomah, Wasco, Clackamas, Marion, Linn, Crook, Lane, Douglas, Jackson, and Klamath Counties. Proclaimed Sept. 28, 1893. Area 4,492,800 acres. (By executive order of June 29, 1901, 46,050 acres were eliminated, and by Proclamation of July 1, 1901, 142,080 acres were added, making a total area of 4,588,800 acres.)

Ashland Forest Reserve — Jackson County. Proclaimed Sept. 28, 1893. Area 18,500 acres.

(Taken from Report of Commissioner of General Land Office 1898, page 95, and report of 1901.)

The following is an excerpt from the annual report of the General Land Office for 1899, which describes the organization of the reserves. Page 101:

The reservations were grouped into districts, with a forest superintendent in charge of each, who is directly responsible to this office for the proper administration of the reserves under his care. Each superintendent's district is divided into supervisors' districts, the number depending upon the number of reserves and the difficulties of supervision, and for each district a supervisor is appointed who has immediate charge thereof under the general supervision and direction of the superintendent. Each reserve is then divided into ranger subdivisions, and forest rangers, who are under the personal direction of the supervisors, are assigned to these divisions, their primary duty being to patrol the reserves, to prevent forest fires, and trespassers and depredations from all sources.

The organization of the force began early in July 1898, but the forest superintendents did not enter on duty, on the average, until about Aug. 8, 1898, and the supervisors at a little later date. The rangers were appointed as fast as suitable men could be selected. This force was not, therefore, organized at a sufficiently early date to deal with the most trying period in the reserves, which begins in some portions of the country not later than June 1.

The maximum force during Calendar Year 1898 was: Superintendents 11; Supervisors 34; and Rangers 215. The force was gradually decreased until on Jan. 1, 1899, there were but 10 superintendents, 17 supervisors, and 50 rangers.

Binger Herman

Commissioner

ADMINISTRATION OF THE CASCADE RANGE FOREST RESERVE

Captain Salmon B. Ormsby of Salem was appointed Superintendent for Oregon by Binger Herman, Commissioner, having supervision of all three of the reserves.

The following are quotes from "The Democratic Times" published at Jacksonville, Oregon, which describe the work of the forest officers:

July 21, 1898:

Hon. N. (Nathaniel) Langell of Jacksonville has been appointed U. S. Forester (Forest Supervisor) at a salary of $5.00 per day. He will guard against the destruction of timber by fire or otherwise on the Cascades, a territory extending from the Umpqua Divide to the limits of the Reserve south, and will have the appointment of five forest rangers. The party will leave for the scene of their duties about August 1. Mr. Langell's appointment gives general satisfaction.

July 25, 1898:

Hon. N. Langell leaves next week with his party of forest rangers for the Cascade Reserve. He has appointed the following deputies: W. J Stanley of Ashland; C. C. Presley of Woodville; I. M. Muller of Medford; Henry Ireland and Jas. D. Fay of Jacksonville. The compensation of the deputies is $50 per month, and their duties are to look out for fires and to see that no depredations are committed on the Reserve.

Aug. 15, 1898:

Big fires in timber between Pelican Bay and Lake of the Woods are raging and forest rangers are engaged in subduing the flames.

Aug. 18, 1898:

Hon. N. Langell, Forest Inspector (Supervisor) left yesterday for Prospect which will be his headquarters until Nov. 1. He was accompanied by his wife and son Harry.

Forest fires on Applegate are not burning so fiercely since Bro. Langell's forest rangers went on duty.

The forest fires in the vicinity of Lake of the Woods are not burning as fiercely since they were attacked by I. M. Muller and W. J. Stanley, the forest rangers.

Sept. 18, 1898:

Forest fires are not burning so fiercely and the atmosphere is comparatively free from smoke, thanks to Uncle Nat Langell and his forest rangers.

Oct. 6, 1898:

Hon. N. Langell, chief of the forest rangers, returned to Jacksonville one day this week. His company did good work.

Oct. 31, 1898:

J. D. Fay, Forest Ranger, has returned from the Upper Rogue River Section where he has been ranging during the past three months. Also Henry Ireland.

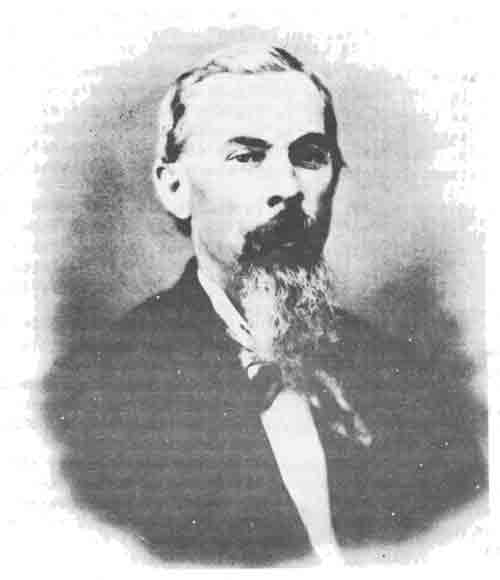

Following is an excerpt on the life of Nathaniel Langell in "Portrait and Biographical Record of Western Oregon" — Chapman Publishing Co., 1904:

"Nathaniel Langell with his father and brother Arthur, moved to Oregon in 1854 when they purchased about 3,000 acres in what is now known as Langell Valley in Klamath County, Oregon. Nathaniel moved to Jacksonville where he conducted a boot and shoe store and repair shop. His father and brother attended to the stock raising. In 1880 Nathaniel disposed of his share of the realty to his brother.

"In 1872 Nathaniel served in the State Legislature on the Republican ticket. In 1876 he was appointed Deputy Internal Revenue Collector for the Southern Oregon District, serving for six years. In 1898 he was appointed forest supervisor which position he held for three years. He then retired from active affairs, living in Medford where he enjoyed his wide circle of friends."

He passed away in 1918 and is buried in the Jacksonville Cemetery, Jacksonville, Oregon.

In 1909 Samuel S. Swenning, Deputy Forest Supervisor, wrote a history of the Forest Reserve (Crater National Forest). The following remarks are taken from his writings under "Miscellaneous History — Personnel".

"It may be of some interest to know something of the personnel which constituted the force of the old Land Office days, the incidents which occurred at that time, and a short biography of each man as can be remembered, but somewhat vaguely, by the writer, and is as follows:

"The first Supervisor was N. Langell, an old resident of Jacksonville, Oregon, who was in charge of the south half of the forest then known as the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. Mr. Langell's headquarters were located in Prospect in the Upper Rogue River country, and during his administration from the year 1898 to 1902 the following men were employed as 'rangers' by him:

"Henry Ireland was the first man in the southern portion of the State who received an appointment as 'Forest Ranger.' His residence and old home at the time being Jacksonville, Oregon, his occupation being that of a broom maker. Mr. Langell, on receiving his instructions to take charge as Supervisor, which were somewhat indefinite, forthwith called on his friend Henry Ireland who was found shingling a house and informed him he had a job for him, but he was unable to give him any definite idea as to the nature of the work except the information that 'it was in the woods.' Therefore, Mr. Ireland and others in due time accordingly left for the mountains and their 'job in the woods.' A few years after this Mr. Ireland is found stationed at Seven Mile Ranger Station near Fort Klamath, Oregon, and by which time the 'Forestry Bureau' and the duties of a Ranger had developed to a degree where the 'job in the woods' was becoming more complicated each season. Mr. Ireland had at first many trials and tribulations officiating as a Forest Ranger, as people in those days were accustomed to look on and to use the public domain as their own personal property, both in timber and grazing matters, and much credit is due Ireland for the able way he managed his district. It is remembered that Ira Hanson, a physical giant and warm personal friend of his, assisted Ireland in many ways in relieving him of the monotony of a ranger's life while stationed in the Klamath country, by threatening his life on numerous occasions and otherwise making himself interesting.

"During a severe winter at the Seven Mile R. S. Ireland's hay became exhausted, but owing to the depth of the snow it was impossible to remove his horses, and he was compelled to sled hay by hand from a ranch some distance away. This sledding affair soon became irksome to Ireland, therefore he impressed the services of a very large fat dog (known over Klamath and Jackson Counties as 'Ireland's Dog'). The sled may still be seen at the Seven Mile R. S. The dog is no more, but Henry Ireland is Forest Supervisor of the Whitman National Forest, one of the most important forests in Oregon.

"Jim Fay officiated as Forest Ranger from 1898 to 1900 inclusive. Before securing his appointment on the Bureau of Forestry he was employed in the newspaper trade. Mr. Fay is remembered as a good worker, however his ability to navigate the woods was considered somewhat questionable. Among the many episodes of Mr. Fay's in the tall timber, may be mentioned an occasion when he attempted to pilot a pair of his friends from his camp at Lake of the Woods to the summit of Mt. McLaughlin, a distance of a few miles. After traveling for two days they finally arrived in the night at a point within 100 yards of the waters of Fish Lake, a distance of six miles from their camp at Lake of the Woods, and where they proceeded to make a 'dry' camp and spend the remainder of the evening, taking care to securely fasten their steeds to trees. They gave vent to their awful plight by doleful cries of distress, and many discharges of weapons. These sounds in the night awakened the writer and a companion (who were at the time spending a few days at Fish Lake looking after stock) and who made haste to cross the lake in a canoe in order to investigate the disturbance. After advising Ranger Fay and his party of his whereabouts and suggesting to them that water might be found in the lake, and after giving careful directions as to the manner of their safe return to their camp, it may be added that they were admonished somewhat in the way and law of the woods. At this time it seems that also other 'Forest Rangers' had considerable difficulty in finding their way from place to place and accordingly Supervisor Langell made efforts to have the stockmen blaze trails in order that the Rangers could travel about without inconvenience. This request was ignored as it seems stockmen had more important business than blazing trails for rangers.

"Jim Fay not being able easily to learn the way of the woods resigned, and has since then been continually employed in the printing shops of Medford, Oregon.

"Clarence Presley was also employed during the season of 1898 only. His occupation being that of a pedagogue. This party was an efficient man but as the pay was inadequate he resigned for a better position.

"W. J. Stanley was an ex-County School Superintendent of Jackon County, Oregon. He resigned after the first season.

"Ike Muller, whose occupation was that of a bookkeeper, was not anxious to trust himself any distance from the regularly travelled highways; therefore, after the one season of experience as a Forest Ranger, he is found back at his usual vocation — that of keeping books."

|

|

Forest Supervisor Nathaniel Langell Cascade Forest Reserve (South) Ashland Forest Reserve August 1, 1898-1901 (Prospect) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

6/rogue_river/history/1/part1.htm Last Updated: 15-Jun-2012 |