Looking at Prehistory:

Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 12,000 B.C. to 1650

|

|

Looking at Prehistory:

Late Archaic Period 4,000 to 1,000 B.C.

The Late Archaic period in southern Indiana is

represented by numerous archaeological sites, including small camps and

large base camps established on a seasonal round that included nearly

every type of habitat--the swamps, creeks, rivers, uplands, and prairie

areas. A very substantial Late Archaic occupation took place within

rockshelters in the Hoosier National Forest and at many sites scattered

along the Ohio River and beyond. Shell mounds, consisting of huge

amounts of discarded shells from the freshwater mussel, accumulated at

major base camps on all the large streams and rivers along with the

bones of fish, fish hooks carved from bone, polished stone atlatl

weights, projectile points and many other tools and artifacts (Figures 48-50, 52).

Such sites as Crib Mound in Spencer County, Breeden in Harrison County,

and Bono in Lawrence County, are notable shell mound sites (Figure

51).

|

|

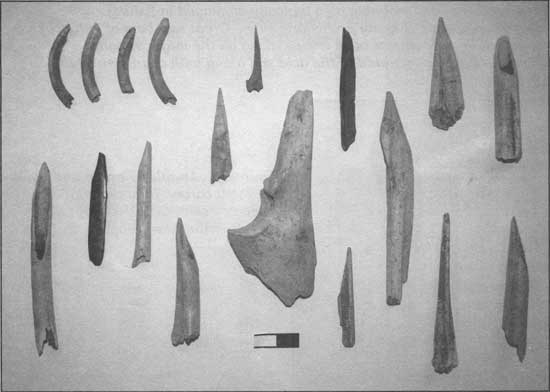

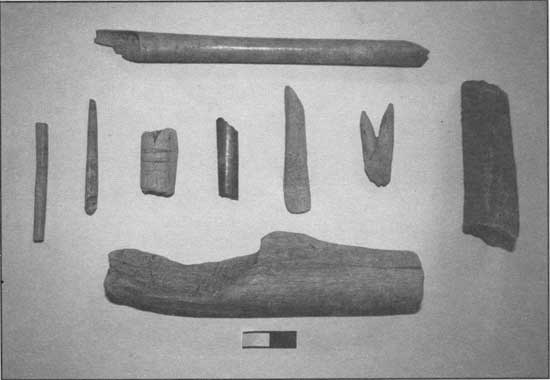

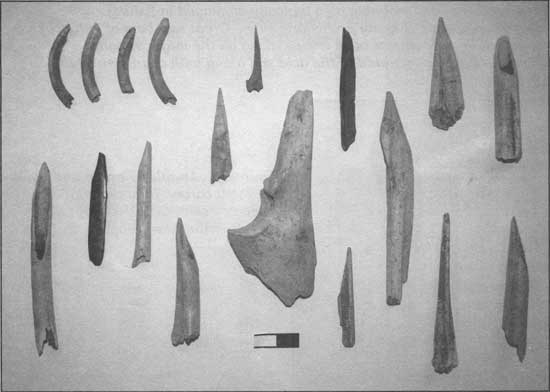

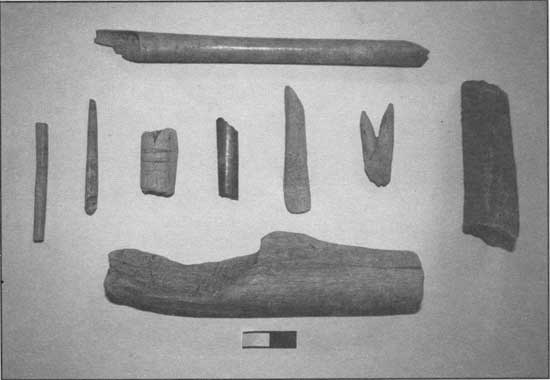

Figure 48: Prehistoric tools made from the bones of deer, fish, birds

and other animals. Many of these were used to punch holes for stitching

buckskin clothes and hide coverings, as well as weaving, basketry, and

many other uses. Rodent incisors made good wood carving tools (upper

left). The catfish spine (center) would work well almost without

modification as a needle or punch.

|

|

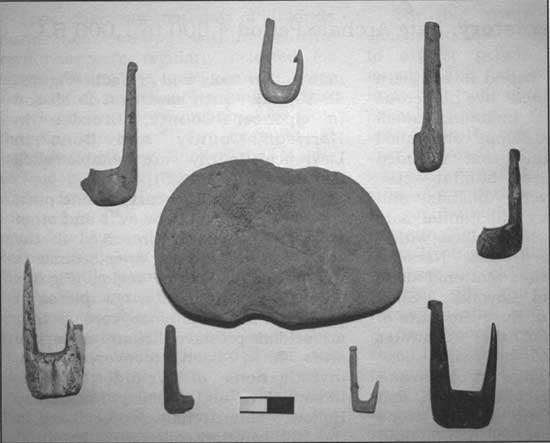

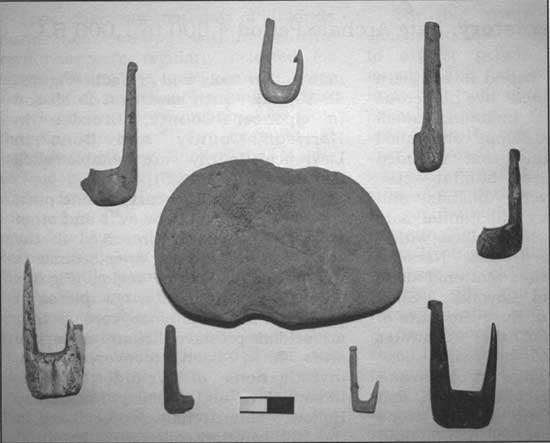

Figure 49: Carved bonefish hooks and a net weight from Crib Mound and

the Elrod site, Clark County, IN. While quite suitable for individual

angling, such items were probably used in multiple sets and combined in

ingenious ways with the use of nets, fish weirs and other equipment.

Depending on the time of year, the depth of the water, fishing location,

number of fisherman, and the desired catch, everything from spears to

clubs and poisons were probably also typically employed in fishing.

Bone preservation is poor at many prehistoric sites. Great numbers of

fish hooks were probably used and left at summer base camps along all

the major streams. Unfortunately, over time they deteriorated in the

acid soil along with countless other perishable tools and

artifacts.

|

|

|

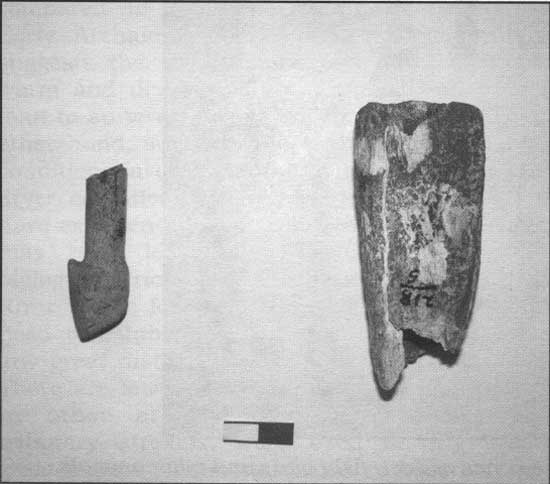

Figure 50: An atlatl handle and hook fragment carved from deer

antler recovered from Crib Mound and Clark's Point, Clark County, IN.

|

|

|

Figure 51: An early photograph of Crib Mound as it was being rapidly

eroded by the Ohio River. The millions of mussel shells discarded in

prehistory helped preserve many otherwise perishable artifacts made

from bone and antler.

|

|

|

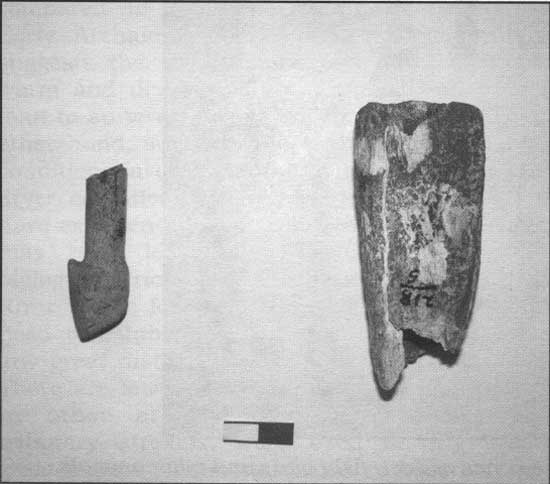

Figure 52: Middle to Late Archaic period atlatl weights of schist and

rose quartz.

|

Highly decorative carved bone pins, pendants,

gorgets, bone awls and other tools are commonly preserved in the shell

mounds and the drier sediments in the shelters of the region (Figures

53-54). In addition, a few pieces of preserved fiber and sinew cordage

that are seldom preserved in archaeological sites have been recovered

from investigations of Wyandotte Cave, Indian Cave and possibly

Rockhouse Hollow. Late Archaic people living in the hill country

collected substantial numbers of mussels along the

shoals of the Ohio and White Rivers that were sometimes carried several

miles inland from the river to be disposed of after meals in

rockshelters and other camp sites. The Bono site, for example, is

located on a bluff top and the mussels had to be carried up the steep

hillside to the site where the shellfish were eaten and the shells

discarded (Figure 55).

|

|

Figure 53: Archaic and Woodland period tools made from deer, bird and

other animal bones. The antler was partially sawed through with stone

tools and then snapped to extract desired pieces. Bone tools are common

in all prehistoric time periods but are found only when the soil

chemistry and environmental conditions allow bone to be preserved.

|

|

|

Figure 54: Carved and decorated bone pins and an

ornament from Crib Mound. The fine incising was probably done with stone

tools and sharpened rodent incisors.

|

|

|

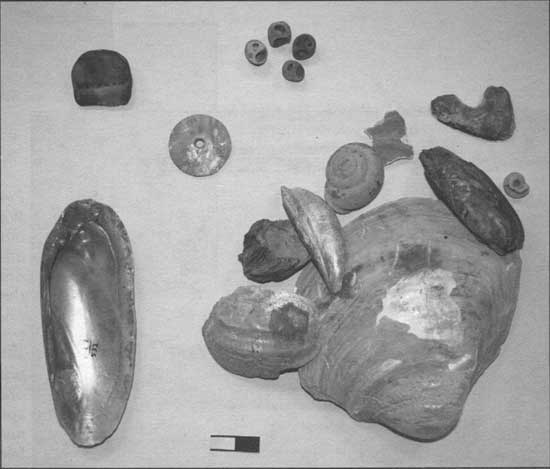

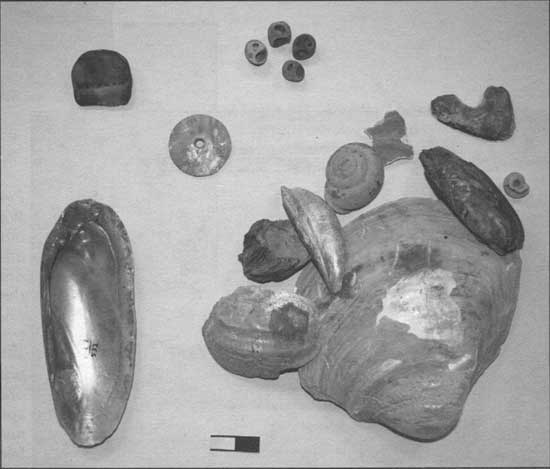

Figure 55: Fresh water mussel and snail shell from Rockhouse Hollow

Shelter, including beads and pendants made from the shell.

|

The French Lick and Maple Creek phases are local

cultural designations for the Late Archaic period in the region

centering on the Patoka Reservoir and along the Ohio River. Karnak,

McWhinney, Matanzas and Brewerton Eared

projectile points are the dominant projectile point

technologies of the time (Figure 56-57). A seasonal round was well

established. It consisted of summer and fall base camps at stream

confluences along the major rivers and fall and winter hunting camps in

rockshelters and various open sites. Matanzas appears to be a smaller

continuation of the earlier side notched tradition, whereas the others

appear to be unrelated technological developments. It remains unknown

if the Brewerton Eared technology expands down the Ohio River Valley

from the Northeastern United States or if it is only a local variation

in the same tradition that produced Matanzas within the central Ohio

Valley. There was a heavy emphasis on deer hunting and the collecting

and processing of nuts of all kinds (e.g. hickory, acorn, walnut,

butternut, chestnut), as well as starchy and oily seeds and some

horticulture at this time to boost food production.

|

|

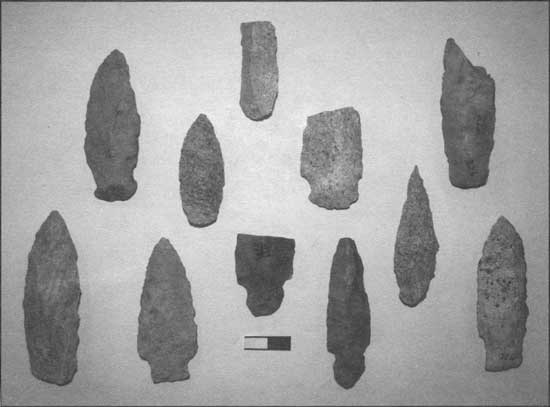

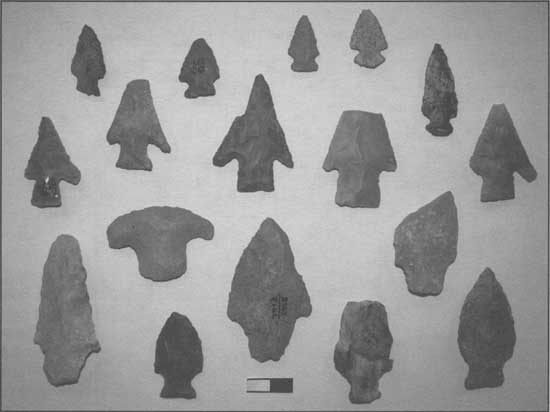

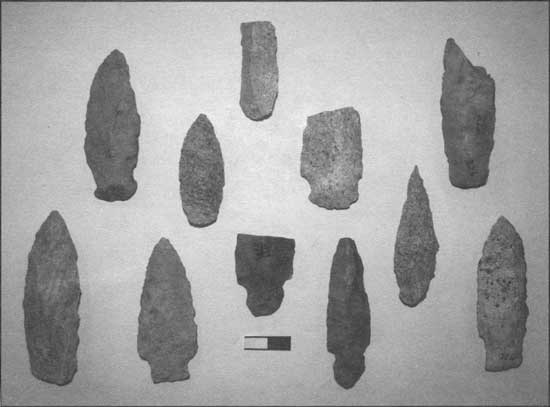

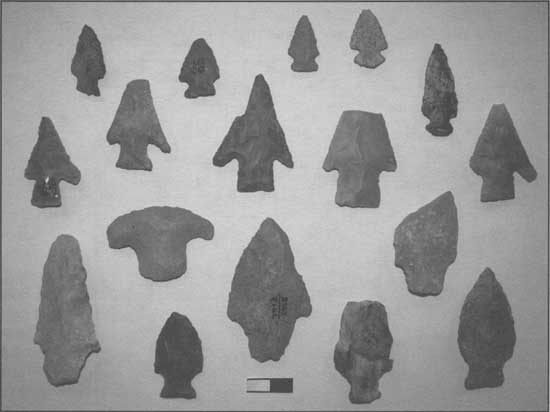

Figure 56: Matanzas and Brewerton Eared projectile points from various

sites in the hill country. Many specimens with blunt-ends are

unifacially flaked for use as scrapers to clean and dress hides.

|

|

|

Figure 57: Late Archaic Stemmed cluster projectile points from sites in

the hill country.

|

Over-hunting of deer along the major rivers may have

been a major reason why people began using small tributary streams and

uplands over all landscapes. In addition, the problem of rapidly growing

local populations required the use of more land for hunting and

collecting to feed more families. Another reason for the widespread use

of all landscapes was the active exploration for microhabitats where

edible plants of all types grow in profusion. Besides the intensive use

of collected nuts for food, we know people all over the Midwest were

using seeds and probably greens of all types of edible plants for food

and medicine. We know this from soil samples collected from excavations

that have been washed carefully to extract small carbonized seeds and

other remains (Figure 58) and then later identified (e.g. flotation

samples). While the heavy use of nuts is indicated at this time from

many open sites and rockshelters, a fragment of

squash rind was recently recovered from Indian Cave.

This site is now added to the small list of archaeological sites in the

Midwest where this plant has been identified. Squash was utilized as

early as 5,000 B.C. and its importance as food continues to increase

until it is finally regular food grown in farms along with other wild

and domesticated plants in the Late Woodland and Mississippian

periods.

|

|

Figure 58: Soil samples recovered during an excavation are being

washed through a fine mesh (flotation) to recover charred seeds, nuts,

and wood charcoal for later identification. Indiana University field

school, 1980. Today we have specialized flotation machines that

circulate the water and make the process more efficient and also recover

more fragile charred material with less damage.

|

Evidence for the preparation of pits probably with

skin liners to boil water with hot rocks is a common theme on Late

Archaic base camps in open locations on the landscape. Base camps often

have tremendous amounts of fire cracked rocks in the middens. These

rocks fractured from the thermal shock of constantly rotating hot rocks

in and out of fires to boil water in nut filled containers. Boiling

methods presumably increased the volume and efficiency in the process of

extracting nut meat and oil from hickory nuts, acorns and other

collected nuts to make more food available. This marks an improvement in

food production, undoubtedly to feed growing families and larger groups

of people (Figures 59-60). The evidence we may have for this at many

rockshelters is mostly circumstantial, as

these sandstone alcoves naturally produced thousands of pieces of rock

fallen from the ceilings that could have been readily used for this

purpose although some pieces are reddened from burning. In any case, had

rounded river pebbles or other foreign rocks been transported to the

rockshelters, their presence would be a more obvious testimony to the

stone boiling technology at this type of site.

|

|

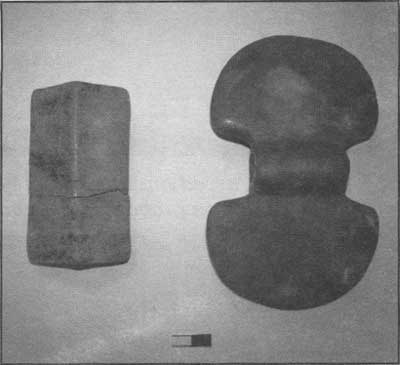

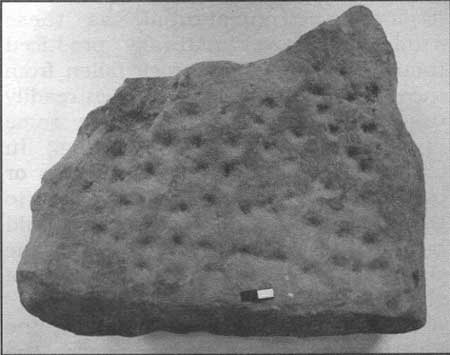

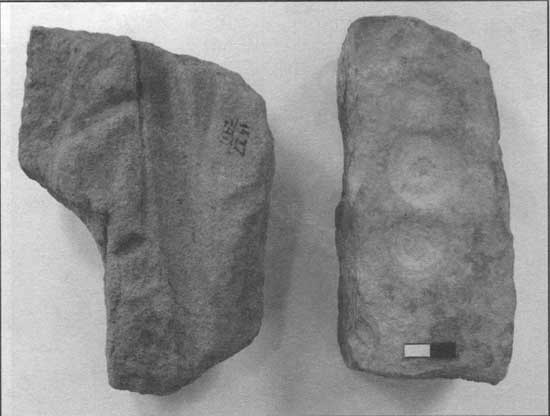

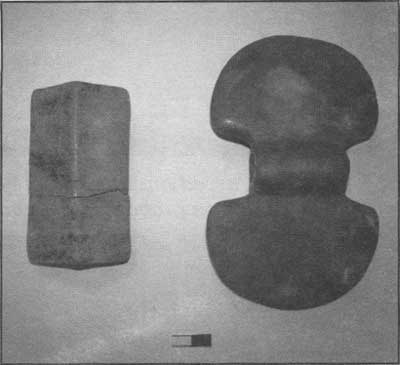

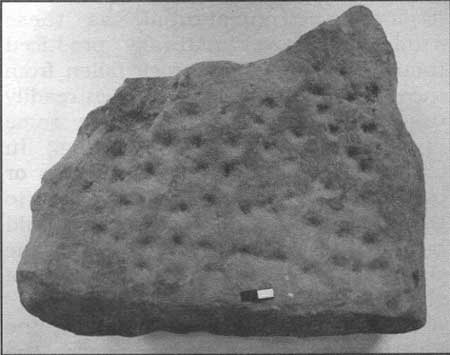

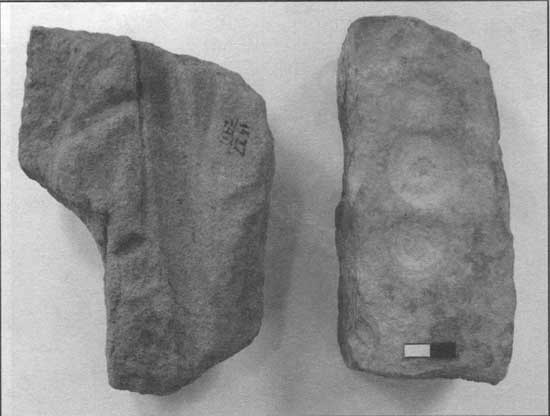

Figure 59: A large nutting stone with multiple pits to make the work

of cracking large volumes of nuts more efficient. Imagine several

families involved in transporting collected nuts in baskets back to a

seasonal camp where they would crack the nuts using several large

nutting stones and stone hammers. They would then boil, parch, and cook

the nutmeat for making breads, soups and other foods and also extract

the nut oil for various uses. Late Archaic people sought ways to make

food production more efficient and began growing and tending wild plant

foods. Creating a surplus allowed them to store prepared food for lean

times and focus on making craft items for exchange and trade with other

groups.

|

|

|

Figure 60: Sandstone abrader and nutting stone from Rockhouse

Hollow Shelter. The groove on the abrader was probably a slot where wood

and bone tools could be shaped and sharpened.

|

Toward the end of the Archaic, the Riverton and other

cultures appear. The Riverton people employed rather small side and

corner notched projectile points to arm their spears that were often

made from small chert pebbles collected from river gravel. They also

left substantial middens of dark organic soil at their base camps

testifying to the intensity at which they harvested and processed a wide

range of animals and plant foods. The Riverton people, along with other

cultural groups, are recognized mainly by the projectile point types

they produced such as Buck Creek Barbed, Turkey-tail, and Ledbetter,

etc. These peoples occupied all areas of southern Indiana

including the hill country of the Hoosier National Forest (Figure

61).

|

|

Figure 61: Late Archaic period projectile points

including Table Rock cluster, Ledbetter, Buck Creek Barbed, and

Riverton cluster types from bottom to top.

|

Beginning about 2,500 B.C. the Late Archaic period in

the Midwest is marked by long distance trade in copper, marine shell and

other items coming from the Great Lakes and Gulf Coast areas. Although

located nearly midway between these source regions, none of the sites

within the Hoosier National Forest show evidence of being the final

destinations for exotic trade goods, but people in the area probably had

a direct involvement in the trade nonetheless. Copper came mostly in the

form of beads, bracelets and awls, and less often in lumps of raw copper

(Figure 62). Marine shell was often made into beads and other decorative

items such as gorgets. Many other kinds of perishable goods could have

been used for exchange and payment for moving marine shell, copper, and

other articles through tribal territories to destinations many miles

away. The perishable goods no longer survive as testimony to the vast

exchange network in commodities that

must have existed. Some of the trade routes probably

utilized the ridge tops for easier movement north to south through the

hill country.

|

|

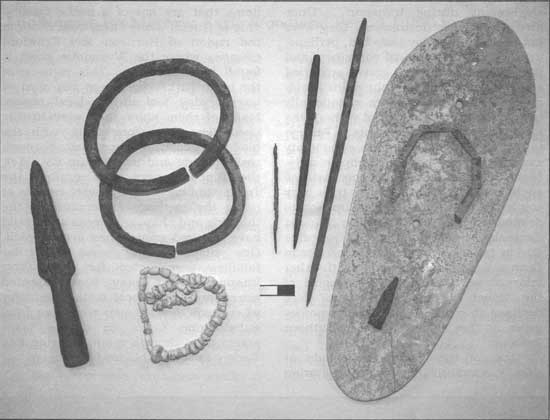

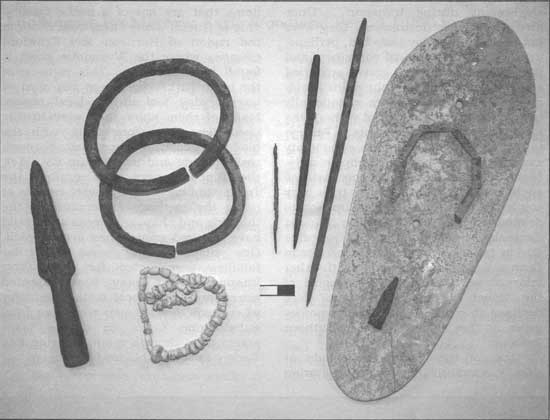

Figure 62: Copper and shell artifacts. The large shell item is a

"sandal-sole" gorget. The copper spear on the left is typical of the

Lake Superior region where the copper was mined. Such items, if they

were traded south, may have been reformed into beads, awls, and

bracelets because few, if any, spears of this type have been found

outside of the Great Lakes area.

|

One important trade commodity which was made at the

Wyandotte chert quarries near Corydon was the Turkey-tail point (Figure

63). Many large sites in the vicinity of Harrison County show intensive

industries were active producing numerous thin and finely crafted

Turkey-tails for use in a vast trade that distributed them into Ohio,

Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and Ontario. These are called Turkey-tail

"caches" that consisted of several to many fine specimens that were kept

together as a group. Excavations of Turkey-tail caches often show the

specimens were nested together, suggesting they were bundled for

safekeeping during transport. Once arriving at their

destination, they were not used for everyday tools but, perhaps, kept

within their original containers and soon placed in honored graves or

buried as offerings to deities in the spirit world. Some of these caches

were intentionally broken at the time of burial without the loss of any

of the fragments. Turkey-tails were probably a main commodity exchanged

for copper lumps, awls, beads and bracelets. Copper articles such as

these were making their way south from mines on Lake Superior to

destinations to the south in Illinois, Kentucky, and Indiana. One fine

Turkey-tail cache is recorded for a site in Orange County which, along

with other information, suggests at least some of the finest Turkey-tail

caches were destined to be used in local ceremonies never to be traded

out of southern Indiana.

|

|

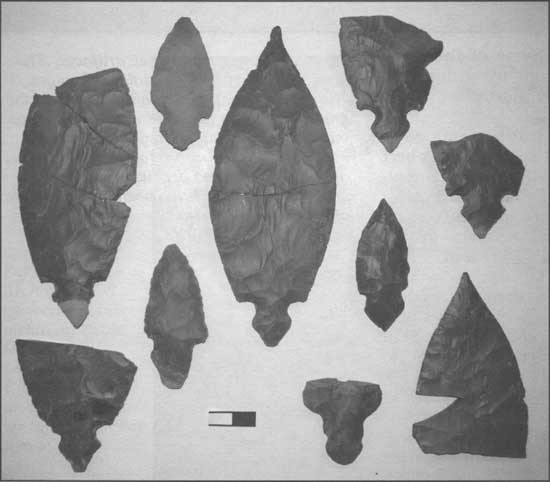

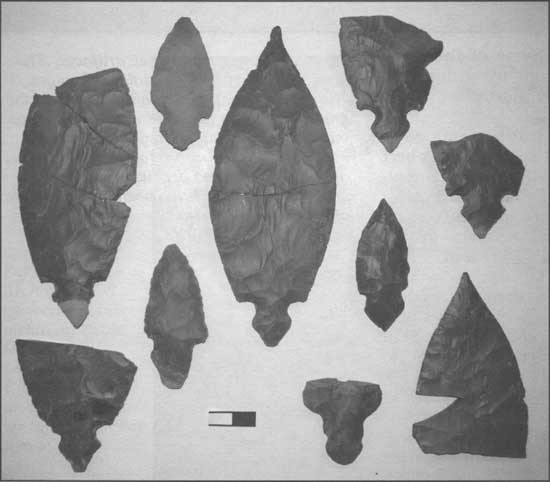

Figure 63: Turkey-tails from sites in the hill

country. The larger specimens are reconstructed from fragments surface

collected over many years from a site in Orange County that were donated

to the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology.

|

Most of the Turkey-tails made at sites in southern

Indiana are utilitarian items that are not of a cache quality. This is true

at many sites, even those in the region of Harrison and Crawford

counties where the Wyandotte chert is found in abundance. This is

because the basic Turkey-tail shape was used as an everyday tool in the

local region. Many of them show they were heavily used like other stone

tools, with the blades becoming shortened through resharpening and use

(Figure 63). Yet, the flint-knappers who crafted the Turkey-tail cache

blades were experts at using the methods for controlling the thinning

and shaping process and would have required greater than average skill.

One suspects that some particular families were noted for their flint

knappers, who may have adopted something like a local cottage industry

where expert craftsmen were free from subsistence tasks to devote large

amounts of time to manufacturing fine Turkey-tail cache blades for

trade.

9/hoosier/prehistory/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |

|