|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

FORESTRY IN THE PUBLIC SERVICE

Forestry is an expanding profession. The land on which our forests grow covers about one-third of the area of the United States. In both the privately owned and the publicly owned forests is work for foresters. At present, the Government, State and Federal, controls only about one quarter of this land, but gradually it is buying land on which the owners have not been able to make a comfortable living; taking over tracts on which the taxes have not been paid; and in a few instances, receiving land as a gift. More land and larger forests require more men to care for them. Then, too, more and more things are done for the forests in order that more may be expected from them. This intensive forestry requires more foresters to the acre.

The United States Forest Service offers a career in which a man enters at the bottom and works up. But he must be the right man. He must be content without growing rich. The Forest Service offers security but not wealth, and over and above all he must realize that his work is to serve people and that trees are merely the tools to that end.

How can a boy who has the various physical and mental characteristics that are required of a forester prepare himself for his profession?

When he finishes high school he goes not to the woods but to college; for like law, medicine, and engineering, forestry has become one of the learned professions.

Suppose him then, equipped with a college sheepskin and a deep interest in human affairs. Now he must learn what progress means in terms of trees, for, through trees, the forester must get his personal expression as well as contribute his individual service to the world. A course in a forestry school is the minimum preparation for this. Here he will study the natural history of trees—how they look, where they grow, how they act, their genealogy, what species are kin to what other species.

|

| Forester in North Carolina. |

|

| Thinning the forest. |

He must go on to the physiology of trees. He must know the processes of tree life and under what circumstances trees flourish and why they die. He must understand how much light and growing space a forest tree needs and how much water and how much and what kind of mineral food must be in the soil. He must know what this living machine that pumps up water, that creates out of light and air and water and certain chemical ingredients the root and branch and leaf and fruit without which we human beings could not inhabit the earth, is made of. What are these intricate systems of pipes and conduits, these pockets for storage, these tiny flying buttresses? What is the actual structure of bark and cambium and heartwood? How is this machine put together?

He must learn the dietetics of trees as a trained nurse learns the dietetics of children.

Seeding and planting are important phases of his study. He must understand how seeds germinate; how to plant seedlings in the field; how to encourage the seed trees in the forest to sow their own seeds. All these are part of the art of producing and tending forests in order to reap a perpetual harvest.

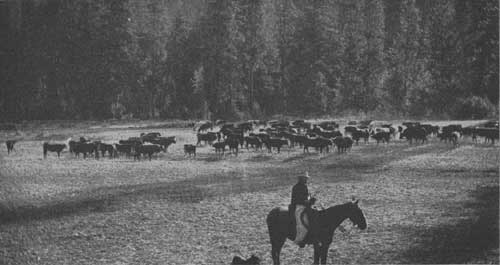

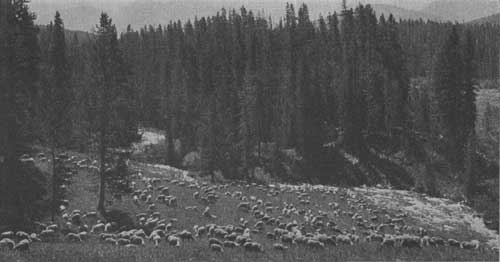

The forest is more than just a place to grow trees. It is among other things a cattle range. A forester must learn the principles of cattle feeding in relation to trees. What, and how much of it, does a cow eat? He must learn how to manage such things as the vast livestock ranges of Idaho. These cover great stretches of sagebrush plain which in the winter is bleak and snow-swept but in the spring blossoms into wonderful pastures. In midsummer these ranges become a dry, brown desert under the summer sun, and no grazing must be allowed until they are revived to life under the early rains of autumn. During that midsummer the forester must see to it that the cattle go higher up the mountainsides into the primitive forests where the snow is melting and the summer feed is thick under the great trees; and when winter comes, he must know that the cattle have all been withdrawn from the national-forest range where hunger would make them destroy the growing forest, and sent back to their home ranches for winter food.

After 4 years of college and the 2 years of study in a school of forestry, the gate into the United States Forest Service opens through the regular civil-service examinations which the Government holds every year. Directly from the civil service lists are selected the junior foresters and the junior range examiners.

|

| Cattle in the forest, Washington. |

|

| Sheep in the forest, Montana. |

From one position to another the forester can advance only on his own record of achievement. Until he attains to an administrative position there is no certainty that he will stay in one place long enough to establish a permanent home.

Along the forester's upward path are branches which may lead him to different goals. There is one path which will lead him into research—either in one of the experiment stations or into the great Forest Products Laboratory at Madison, Wis. Another may lead him to the administrative branches of the work. Another to that rapidly enlarging field of public relations which heads up in Washington. Usually he does not spend the whole of his professional life in the adventurous outdoor side of the work. The line of promotion leads him generally into some central office, where he can combine field work with the life of cities.

But these men revert—these promoted foresters. When the spring comes their eyes go into long range, and they see the buds swelling on the treetops in the forests they have cared for. In the autumn they yearn to tuck their forests in for the winter, and it is obvious to the humblest observer that they have got to go out and look at their trees.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/sec12.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |