|

Whitman Mission

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER TWO

EVENTS LEADING TO THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE WHITMAN MISSION NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

|

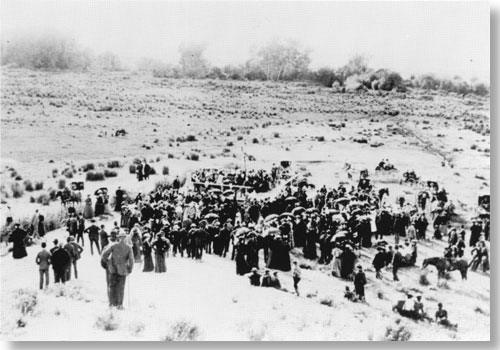

| 50th Anniversary of the Whitman Massacre, 1897 |

Commemoration of the Whitmans began long before the 1916 establishment of the National Park Service. In 1859, only twelve years after the Whitman massacre, the Reverend Cushing Eells received a charter from the Washington Territorial Legislature for Whitman Seminary in honor of his colleague. The commemorative efforts by Dr. Whitman's friends and associates and later by concerned local citizens generated interest in the Whitmans that attracted the National Park Service to Walla Walla. Therefore, these early memorial efforts deserve recognition, as they laid the foundation for the present-day national historic site.

William H. Gray's Campaign

In addition to Reverend Eells, another of Whitman's colleagues attempted to commemorate him on the location of the mission grounds. William H. Gray, once the mission's carpenter but by 1874 the "zealous Corresponding Secretary" [1] of Astoria's Oregon Pioneer and Historical Society, began raising funds to improve the common grave of the massacre victims. Located near the mission site, the grave was simply a dirt mound surrounded by a picket fence. Gray was appalled by what he considered the neglect of "the graves of Christian and Patriotic dead" [2] and by 1882 procured lumber for a new fence. In 1885, under the direction of President A. J. Anderson of Whitman College, a picket fence was built around the graves, which, with little repair, lasted until 1897. [3]

Equally important to Gray, though more controversial, was the establishment of a monument "to commemorate the daring and unselfish deed of Dr. Whitman." [4] In 1874, the Oregon Pioneer and Historical Society appealed to "the people of Oregon" (and the people of Washington, Idaho, and Montana) to contribute to "the erection of an appropriate Monument to the memory of our lamented Dr. Whitman, who fell a martyr in defense of Truth and Justice . . . in 1847." [5] The Society organized a committee called the Monument Association, and under Gray's direction this association solicited contributions from Presbyterian and Congregational churches, newspapers, and citizens throughout the Northwest and Walla Walla. Initially, Gray estimated the shrine's cost between $20,000-$25,000 [6] given its elaborate design:

The idea is to include the names of fifteen persons, with a granite base five feet high; a man, with or without, his wife, a noble looking woman by his side, and with or without, thirteen other bodies represented as slain lying around them. The man is to stand as the central figure with a book in the left and the American flag in his right hand. [7]

Shortly thereafter, plans were scaled down to a simple Celtic cross [8] priced between $6,000-$8,000. [9] Though the Walla Walla Daily Statesman reported that Gray's plans met with the "hearty concurrence" [10] of the community, some felt Walla Walla was a better site for the Monument. [11] Others believed that the real monument to Marcus Whitman was Whitman College, the successor of the Whitman Seminary, and so would not support Gray's plans. [12]

A more serious setback occurred in 1880 when "[the Association] learned, after collecting . . . $417.30 that we had no land on which to erect the monument." [13] Fund raising slowed but did not stop while the Association tried to secure the needed acreage. Then, in 1881, Charles and Lucinda Swegle, owners of the mission property, gave to the Oregon Pioneer and Historical Society warranty deed to seven acres which included the grave site and hill on which to build the monument. [14] The Society agreed to the additional stipulation that they erect the monument within five years, by 1886. [15] Although the exact number of years Gray solicited funds is unclear, the Oregonian estimated he canvassed "with more or less vigor up to the time of his death." [16] By the time of Gray's death in 1889 [17] it is also unclear how much money the Monument Association raised, [18] although $800.00 is a common estimate.

While erecting a monument to Marcus Whitman was an Oregon Pioneer and Historical Society project, Gray was the impetus behind the entire movement. In fact, the Walla Walla Union noted that Gray's "chief aim in life appears to be to secure funds and erect a monument on the neglected grave of Dr. Marcus Whitman." [19] Although Gray failed to achieve his goal, he was instrumental in keeping the memory of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman alive. His commitment to memorialize the Whitmans at the site on which they had worked and died brought new attention to the mission grounds. The first step toward a monument had begun.

The Monument Association, 1897

Little was done to further Gray's efforts until 1896 when, according to W. S. Holt, "The neglected condition of the grave was brought to the attention of the Presbyterian Ministers' Association [of Portland] by one of its members." [20] Given the approaching 50th anniversary of the massacre, this neglect was intolerable to the Association. As a result, church members discussed holding a "suitable celebration at the half century mark of [the Whitmans'] death, and also to have erected the monument contemplated by Mr. Gray." [21] A committee formed, composed of members from Oregon, Washington, and Idaho and led by President H. W. Corbett, Treasurer William M. Ladd, and the managing committee, Curtis C. Strong, W. S. Holt, and George H. Himes, all of Portland. [22] Under their direction, the reactivated "Whitman Monument Association" [23] generated funds for a marble grave slab and memorial shaft.

In 1897, the Reverend E. N. Condit, Dr. A. K. Dice, Allen Reynolds, and W. S. Holt "called upon the owner of the land and told him of the project." [24] As a result, Marion W. Swegle donated the seven acres, previously owned by the Oregon Pioneer and Historical Society, to W. S. Holt, Levi Ankeny, and Allen Reynolds, Trustees of the Walla Walla Trust Foundation. [25] Since the Oregon Pioneer and Historical Society failed to erect the monument as stipulated in their 1881 agreement with Charles Swegle, the acreage presumably returned to the Swegles' possession, allowing Marion Swegle to re-donate the land eleven years later. (see map, Appendix A)

In August 1897, Holt, Strong, and Himes signed a contract with Walla Walla's Niles-Vinson marble works for "fences, mausoleum, and monument at the grave of Dr. Whitman" for $2,100.00. [26] Significantly, the contract stipulated that the Memorial Association was not liable for payment and that payment was due when the funds were raised by voluntary subscription. [27] The twenty-seven-foot-high granite shaft and marble grave marker, although completed by November 29, 1897 did not arrive from Vermont in time for the memorial observance. However, the 3000 people attending the semicentennial ceremonies heard speeches by Catherine Sager Pringle, a massacre survivor, and the Reverend J. R. Wilson, followed by a program at the Walla Walla opera house. [28] The grave marker and shaft were in place by January 1898, although a $1,1000.00 debt, more than half the original cost, still existed ten years later. [29] The Association failed to collect sufficient funds in 1897, yet the original contract left the members free from liability so the debt remained.

When the Presbyterian synod met in Walla Walla in 1907, Edwin Eells, Stephen B. L. Penrose, the Reverend James C. Reid of the First Presbyterian Church of Walla Walla, and the Reverend Austin Rice of the First Congregational Church of Walla Walla assumed responsibility to liquidate this "debt of honor." [30] They asked each denomination to raise $550.00 before the sixtieth anniversary of the massacre [31] although it is not clear whether they succeeded.

While the 1897 Whitman Memorial Association failed to fund the shaft and gravemarker, they succeeded in fulfilling William H. Gray's dream. Thus, the Memorial Association's greatest contribution was erecting the shaft and grave marker which, for the next forty years, remained the sole reminder of Waiilatpu's eleven-year existence.

Maintaining the Monument, 1900-1936

Care of the Whitman grave and memorial shaft fell to various local groups from 1900-1936. Unfortunately, this eight-acre site was neglected during the early 1900s in spite of an attempt by the Washington State Legislature to establish a Whitman Park Commission and purchase the mission property for a state park. [32] However, some development occurred. Marion Swegle donated one more acre of his property for the Whitman-Eells Memorial Church, built south of the Great Grave at the base of Shaft Hill. [33] (see map, Appendix A and B) The church remained at this location until approximately 1923 when it was moved to Milton-Freewater. [34] Another change occurred in 1914 when the bodies of William and Mary Gray were moved from Astoria and placed beside the Great Grave. [35]

With the exception of the Whitman-Eells Church and the additional grave marker, the site's appearance did not change greatly until a series of title transfers facilitated some noticeable grounds improvements. In 1923 the Walla Walla Trust Foundation, owners of the eight acres, and the Whitman-Eells Memorial Church (now defunct) transferred their holdings to the Union Trust Company as a perpetual trust to the public. [36] This company became the trustee for the Walla Walla Trust Foundation. Eventually, the Union Trust Company went through a series of mergers and became part of the First National Bank of Walla Walla and later the Seattle First National Bank, Walla Walla Branch. [37] About this time, the Walla Walla Kiwanis Club became interested in the mission after John Langdon, a local businessman and Kiwanian, suggested beautifying the monument grounds. Predictably, a committee formed to manage the project. Phillip Winans, Henry Marshall, and Chase Lambert organized the "Whitman Monument Committee," and in 1923 the Kiwanis Club assumed responsibility for maintaining the grounds. Since their ability to improve the grounds depended upon an unclouded land claim, Winans and Herbert Ringhoffer took the necessary legal action to clear title to the entire mission claim which totaled 646.89 acres. Representative John Summers introduced the bill into the U. S. Congress and on June 21, 1926 Congress issued a patent for Donation Claim No. 37 and No. 38--the Whitman Mission--to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the group which had sponsored the Whitmans in their missionary efforts. The A.B.C.F.M. deeded the land to the then owners (the Swegles), clearing the title. In this action, approximately eight acres composing the land held as a public trust by the Union Trust Company was held out as a public park. [38]

The legal issues settled, the Kiwanis established an endowment fund for grounds improvement: "[the Kiwanis] believe pioneers of the valley and the state will be glad to contribute to an endowment fund so the [monument] grounds may be kept beautiful for all time." [39] True to their plans, the Kiwanis designated the area "Whitman Memorial Park," built an entrance sign, and improved the road to the grave and monument. They are also credited with building four pit privies that were located on the mission grounds from the mid-1930s until 1963. Mr. Howard Kaseberg, a Kiwanis member in the 1930s, remembers spending his weekends cleaning the grounds and planting shrubbery. To him it seemed "a natural project." [40] The Kiwanis were joined in their landscaping efforts by the Daughters of the American Revolution who, in 1931, designated the Whitman Monument grounds as the most historic spot in the Pacific Northwest." [41] After 1935, when the Whitman Centennial, Incorporated, formed, in part, "to assist in the care of the Whitman Monument," [42] Kiwanis involvement faded, although they continued to care for the grounds until 1939. [43]

|

| Whitman Mission was designated "Whitman Memorial Park" by the Kiwanis during the 1920s and 1930s. |

The Kiwanis were responsible for maintaining and improving the grounds during the 1920s and 1930s. Their work generated interest in the mission which had otherwise declined since the semicentennial years. After 1935, it became the responsibility of the Whitman Centennial, Inc., and the National Park Service to improve upon their efforts.

THE WHITMAN CENTENNIAL, INCORPORATED

In February 1935, the Walla Walla Chamber of Commerce appointed a committee to "inquire into the desirability of having a Centennial Celebration to commemorate the 100th Anniversary of the coming of Dr. Marcus Whitman and his party to Waiilatpu." [44] In reaction to the favorable response, the Whitman Centennial, Inc., "a charitable and benevolent corporation," [45] was formed under the leadership of Herbert G. West, Harold Davis, and Alfred McVay. In addition to celebrating the centennial, the corporation's major goal was to "acquire, maintain, and operate a park at the place of the Whitman Mission." [46] West believed that the best way to maintain the mission and to recognize Whitman's role in preserving Old Oregon for the United States was to restore the buildings and establish a national monument. West asked U. S. Representative Knute Hill and U. S. Senator Homer T. Bone to introduce bills in the respective houses of Congress to provide for the establishment of the Whitman National Monument and restoration of buildings and grounds. [47] As a result, H. R. 7736 was introduced on April 25, 1935.

The Centennial Corporation's action occurred shortly before the passage of the 1935 Historic Sites Act which declared it national policy "to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings, and objects of national significance." [48] Administration of this act fell to Verne E. Chatelain, Acting Assistant Director, National Park Service. Dr. Chatelain advised the Whitman Centennial, Inc., to purchase the mission property and donate it to the government, and to prepare a brief requesting a national monument. [49] Accordingly, C. Ken Weidner prepared the brief while the Whitman Centennial, Inc., sold $1.00 and $10.00 corporation memberships to raise funds to purchase the mission property. [50]

In the meantime, Dr. Chatelain requested Olaf T. Hagen, Acting Chief of the Western Division, Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings, to investigate the proposed national monument site, which he did on April 17 and 18, 1936. Hagen favored the idea of a national monument and recommended that the eight acres belonging to the Walla Walla Trust Foundation "should be incorporated as part of the Monument." [51] In addition, he recommended expanding the western, eastern, and southern boundaries and securing easements on all adjacent property to protect the historic scene.

While the Whitman Centennial, Inc., prepared for the Centennial Celebration and the National Park Service surveyed the mission property, H. R. 7736 was presented to Congress. The bill provoked little debate until May 21, when the House refused to accept an amendment submitted by the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys. The committee's amendment deleted section four of the bill which stated, "There are authorized to be appropriated such sums as may be necessary to carry out the provisions of this Act." [52] House members Rene L. De Rouen of Louisiana, Knute Hill of Washington, Harry L. Englebright of California and Senate members James E. Murray of Montana, Elmer A. Benson of Minnesota, and Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota were appointed to a conference committee to end the debate. On June 3 they recommended "that the Senate recede from its amendment." [53] Thus, the bill passed with appropriations, and was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, June 29, 1936.

Two months later, in time for the August 13-16 centennial celebration, the Whitman Centennial, Inc., raised the $10,000 with which to purchase the mission property. On September 29, 1936, J. C. and Della Fentress deeded the 37.21 acres to the corporation. Thus, in 1936 the 37-acre "mission tract" belonged to the Whitman Centennial, Inc., while the eight-acre "monument tract" (comprising the grave and shaft) still belonged to the Walla Walla Trust Foundation (see map, Appendix C). Walla Walla citizens' generous contributions not only enabled the Whitman Centennial, Inc., to purchase the mission property but to raise an additional $822.46. [54] The achievement did not belong to the Whitman Centennial, Inc., alone, but to the entire city.

Overall, the Whitman Centennial, Inc., enjoyed great support. From the beginning, members of the National Park Service favored the Whitman National Monument project and cooperated with Herbert West and the Whitman Centennial, Inc. Yet, why was the National Park Service interested in the Whitman Mission? Hagen of the Historic Sites and Buildings Branch believed Waiilatpu had advantages that made it a good prospect for a national monument:

If the assumption that historic sites possess educational and historic values derived partly through the stimulative or inspirational power of their physical features and their historical associations is correct, then the possibilities of this site would have to be ranked among the best of those in the region . . . . It combines the features of a historic site, a shrine and a memorial. Furthermore, the controversy over the "Whitman Legend" and the connection of the site with the Oregon Trail have given it a widespread publicity that will invite both historian and laymen to the national monument. [55]

From a historical, social and political standpoint, Russell C. Ewing, Regional Historian, Region IV, considered this project to be of national importance. [56] Clearly, the National Park Service was interested in the mission for both its historic and memorial qualities. Yet, the National Park Service's ability to act on that interest was due, in part, to the 1933 reorganization of its system.

Prior to 1933, the government placed relatively little priority on the acquisition of historic sites. Of about 77 national monuments established between 1906-1933, only 17 were historical and 16 were prehistoric significance. [57] An important reorganization occurred in 1933 when the National Park Service became responsible for nearly all Federally-owned parks and monuments. Labor and funds from President Roosevelt's newly-organized Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Project Administration enabled the Service to carry out a program of preservation, restoration, planning, and interpretation of historical areas. [58] Historical technicians, such as Hagen, were hired to "analyze the historical qualities" [59] of areas, the Branch of Historic Sites was established and the Historic Sites Act passed in 1935. The reorganization had a tremendous impact on the scope of the National Park System. Of the permanent additions to the National Park System between 1933-1963, 14 were natural, 13 were recreational, and 66 were historical. [60] Five historical areas joined the System in 1936, none of which were then "national historic sites". Thus, when members of the Whitman Centennial, Inc., were ready to establish a monument, a new national policy enabled the National Park Service to meet their needs.

On November 27, 1936, Herbert West informed Arthur E. Demaray, Acting Director of the National Park Service, that the Whitman Centennial, Inc., was prepared to convey the Whitman Mission property to the U. S. Government. In response, Mr. Demaray outlined the following procedure:

We desire to have a representative make an investigation of the area and submit recommendations as to what the boundaries should be. When these boundaries are determined . . . you may prepare the necessary deeds and abstracts of title with a view to conveying the lands to the United States. [61]

Accordingly, on January 28, 1937, Russell C. Ewing, Regional Historian, Region IV, investigated the mission grounds and agreed with Hagen's earlier conclusions that the monument boundaries should be widened to include the grave site and memorial shaft owned by the Walla Walla Trust Foundation. [62] Inclusion of this property combined with additional expansion of the mission boundary westward and northward "would provide a somewhat more appropriate setting for the mission site and . . . would lend itself admirably to the historic development of the area." [63] said Ewing. However, neither the National Park Service nor the Whitman Centennial, Inc., was in a position to purchase additional property and legal obstacles hindered their efforts to secure the eight acres held in trust by the Walla Walla Trust Foundation. This property was established as a perpetual trust with the public as beneficiary. According to West, "It appears that it is impossible to secure a title to the monument ground, for no one has a legal right to petition the superior court to dissolve the trust." [64] When Branch Spalding, Acting Assistant Director of the National Park Service, notified Regional Historian Ewing that boundary extensions were doubtful, Ewing reluctantly submitted two alternative boundary proposals, neither of which mentioned the Trust Foundation's eight acres. [65] Despite the boundary difficulties, Assistant Director Spalding was not yet prepared to exclude this property from the national monument. He rejected West's request that the monument embrace only those holdings of the Whitman Centennial, Inc., and insisted on incorporating the additional eight acres:

[The Walla Walla Trust Foundation property] is a vital element in the entire project and we do not see how the monument can be established unless the Foundation is willing to relinquish their title to the Federal Government . . . . It is suggested that you proceed with negotiations for that property. [66]

Upon Spalding's insistence, the Whitman Centennial, Inc., began the lengthy and difficult process of clearing title to this property. Cameron Sherwood took responsibility for the project which took three years to complete.

During the intervening three years, the National Park Service continued to plan for the monument's master plan, historical and archeological research, and new entrance road. In contrast, the Whitman Centennial's contribution was limited, as West's 1938 letter to Marvin M. Richardson indicates:

It would have been practically useless to have said anything more back at the National Park Service, in view of the fact that Cameron Sherwood has not quieted the title on the balance of the land to be embraced within the boundaries of the National Park. Until this is done, there is nothing further that we can do. [67]

On May 22, 1939, the Whitman Centennial, Inc., finally secured title to the desired property. [68] Richardson explained that several suits of law had been instituted to quiet the title on the land such as the suit brought against the Oregon Pioneer and Historical Society:

Since the originators of this Society had all died, it was necessary to bring in every one of the many descendants . . . as defendants. By securing quit claim deeds and waivers of right to partial ownership, the title was cleared. [69]

On August 8, 1939, the Assistant Secretary of the Interior accepted the entire 45 acres, subject to final payment of taxes, a possessory rights report, and issuance of a title certificate and insurance policy. [70] Finally, on February 10, 1940, West received notice from A. J. Knox, Acting Chief Counsel, National Park Service, that "conditions have now been satisfactorily met and title to the land is now vested in the United States." [71] The Whitman National Monument was officially established with 45.84 acres under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service.

Both the National Park Service and the Whitman Centennial, Incorporated deserve credit for establishing the Whitman National Monument. Those members particularly committed to this project were Cameron Sherwood, who settled the legal issues, Marvin Richardson, who introduced Park Service personnel to the mission story, and Herbert West, who coordinated the celebration. Without their interest and dedication it is doubtful whether the mission would have received national recognition. In fact, National Park Service Director Newton B. Drury said upon the occasion of the Monument's dedication that "the Whitman Centennial Association deserves full credit for its tireless efforts in the creation of this national monument . . . ." [72] In 1940 the Whitman Centennial, Inc., entrusted their "pet project" to the National Park Service. In return, Park Service representatives Olaf T. Hagen and Russell C. Ewing respected local citizens' ideas and, although they did not promise to implement each suggestion, they regularly informed the public of development plans. By working closely with local experts in this manner, the National Park Service gained valuable information and ensured cooperative and friendly relations with Walla Walla citizens. Established in this climate of goodwill, the Whitman National Monument represented not only five years of Whitman Centennial and National Park Service interest, but nearly a century of community involvement at the Whitman Mission.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

whmi/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2000