|

Whitman Mission

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER SEVEN

RELATIONSHOP WITH OTHER ORGANIZATIONS

|

|

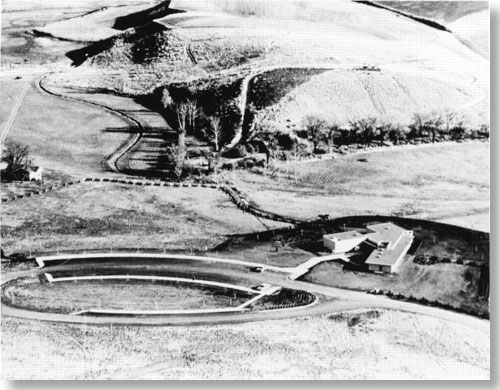

Development site after visitor center and trails were completed in 1963 but before the Frazier house was removed in 1964.> |

Whitman Mission does not exist as an entity unto itself. Instead, the park is dependent upon other agencies and groups for direction and support. Whitman Mission commonly associates with, and is dependent upon, the Federal government, the local community, and its neighbors. The quality of these relationships indicates how Whitman Mission is perceived and oftentimes indicates future direction. Ultimately the quality of a relationship affects park operations. This chapter examines Whitman Mission's relationships beginning with the most apparent and important: the Federal government.

GOVERNMENT

As an area administered by the National Park Service, a bureau within the U. S Department of the Interior, Whitman Mission is affected by directives from Washington, D. C., and the regional office. Government-wide and service-wide goals determine the programs, the resources, and the funds with which administrators work. Superintendent Amdor recognized this when he stated, "The Park Service, like every other organization in government, reacts to various thrusts." [1] The following examines some of the government thrusts that have affected Whitman Mission National Historic Site.

Mission 66

The Mission 66 program, instituted in 1956 to revitalize National Park Service facilities, had the most important long-term impact on Whitman Mission. As a result of Director Wirth's development program, Whitman Mission acquired all the modern facilities in use today: the visitor center, maintenance building, employee residence, the parking and picnic facilities, and the trails.

Environmental Awareness

Midway through Mission 66 the decade of the 1960s opened, with a new concern for environmental problems evident. As the destruction of the American landscape and the pollution of its air and waters moved to front-page prominence, the new Secretary of the Interior, Stewart L. Udall, became the articulate voice of environmental preservation. [2] An early promoter of environmental education, the National Park Service initiated the Environmental Study Area in 1968. Introduced by Director Hartzog, the study areas were located on National Park Service property and designed to educate school children about their environment. [3] This program preceded the National Environmental Education Development (NEED) program, also sponsored by the National Park Service in cooperation with the National Park Foundation and Silver Burdette Company. [4]

Environmental awareness trickled down to Whitman Mission by 1969 when Superintendent Stickler actively promoted the new programs through newspaper and radio. Superintendent Stickler explained Whitman Mission's responsibility to promote conservation in a radio interview in 1969:

The National Park Service has embarked on this program we call Environmental Awareness and since historical areas such as Whitman Mission are an integral part of the system, we are departing a little from our usual program of interpreting the historical story of the Whitmans. [5]

Several environmental films including "The Litterbug," "Troubled Waters," and "Our Living Heritage" were added to the interpretive program and shown throughout the week and on weekends. [6] As a result, Superintendent Stickler reported, "during the summer of 1969, wildlife and other conservation films were shown 85 times to approximately 3,000 people." [7]

Focus on the environment continued into the 1970s. Superintendent Stickler's management objectives for 1971 included broadening "the basic interpretive program to stimulate environmental awareness to the average Park visitor." [8] During the following years, rangers presented talks entitled "Agriculture at Whitman Mission" and "Wildlife, Then and Now." [9] Seasonal Ranger Jack Winchell participated in the local school district's three-week-long environmental workshops. He presented his talk "Pond and Stream Life" to approximately 500 students in 1973 and in 1974. [10] Although Environmental Education was at its height during the mid-1970s, the park interpretive staff currently shows these same films on weekends year-round; evidence of Environmental Education's long-term impact on Whitman Mission.

Equal Employment Opportunity

Superintendent Kowalkowski's administration was the first to implement affirmative action. The Federal government instituted Equal Employment Opportunity programs and offices in the early 1970s; the Pacific Northwest Regional Equal Employment Office was established in 1973.

The Interior Department was quick to employ American Indians in their effort to comply with the new law. In 1972, Secretary of the Interior Rogers C. B. Morton encouraged heads of bureaus to recruit Indians; moreover, he implied it was their obligation: ". . . our efforts in Equal Employment Opportunity should reflect our particular moral and program responsibilities toward the Indians." [11]

Whitman Mission had just introduced its Native American cultural weekend and its "Conflict of Cultures" theme when Secretary Morton's directive was issued. However, the park contracted with Native Americans for cultural demonstrations rather than hiring them seasonally or permanently. [12] The park was more successful in recruiting women and Hispanics for the seasonal ranger and maintenance positions. The seasonal employment summaries from 1974-1977 indicate that while the park was making strides hiring women seasonals (three in 1974, eight in 1975, four in 1976, three in 1977) and minority seasonals (one in 1974, four in 1975, two in 1976, and two in 1977), Native Americans were not hired. These results reflect Superintendent Kowalkowski's goals to "make more personal contacts with organizations and educational institutions that may be sources of recruiting minorities and women," [13] and the belief that the increasingly two-sided interpretive program satisfied Native American Equal Opportunity requirements.

Although Whitman Mission was providing Indians an opportunity to share their culture, in 1978 the adoption of the National Park Service's first comprehensive Native American policy, Special Directive 78-1, provided a mandate to move aggressively to hire Native Americans. [14] Responding to the Native American Freedom of Religion Act, this policy was important to Equal Employment Opportunity because it encouraged "participation of Native Americans . . . as park interpreters." [15] Whitman Mission's Chief Park Interpreter, Dave McGinnis, took this responsibility seriously and set goals to hire Native Americans. [16] He accomplished this goal in 1980 by hiring Marjorie Williams and Maynard Lavadour as cultural demonstrators full-time during the summer and intermittently during the fall and winter. [17]

Just as it was difficult for ranger McGinnis to recruit knowledgeable Native Americans, [18] the new seasonals--the first Native Americans to wear the Park Service uniform at Whitman Mission--were faced with considerable challenges. Ranger Marjorie Williams remembers that reaction from the reservation and the public was "half and half." [19] Some tribal members "complained that we were too young and didn't know what we were doing," [20] while others like Ms. Williams' grandmother, Susie Williams, were supportive. Similarly, some visitors were positive while the reaction of others seemed to say, "What are you doing here?" [21] In addition, Ranger McGinnis expected the new seasonals to be more than cultural demonstrators:

He wanted us balanced. He wanted us to know what happened to the pioneers . . . . We had to read all the books we had on the Whitman story to learn about the Umatilla reservation . . . . It taught us that we didn't know as much as we thought we did. [22]

Ranger McGinnis received an Equal Employment Opportunity award that year for his successful outreach efforts with the Umatilla Indian Reservation. [23]

After 1980, the park employed Native Americans regularly. In fact, Superintendent Amdor inserted a new goal into the 1981 Annual Report: ". . . continued employment of a person knowledgeable of Cayuse culture will be necessary to insure compliance with the N.A.F.R. Act . . . ." [24] The park's first permanent Indian employee was Cecelia Bearchum, hired as a park ranger in 1985. [25] Implementation of Equal Employment Opportunity through seasonal appointments and Youth Conservation Corps enrollees continues each year. In addition, in 1987 several permanent positions were filled with minorities and women. Diana Elder filled the permanent maintenance worker position; Gloria La France is the new administrative assistant; Marjorie Williams, after all her seasons with the park, accepted a full-time park ranger position; while Dave Herrera, of Hispanic descent, is the park's new superintendent. [26]

Energy Conservation

Whitman Mission was not greatly affected by the energy crunch of the late 1970s. However, because of the new energy conservation awareness, monitoring energy consumption became a new management responsibility as of 1977. That year, management's goal was to "achieve a 15 percent reduction in energy consumption in park buildings." [27] This reduction was achieved by turning down thermostats and turning off lights in the museum and audiovisual room when not in use. Several energy conservation programs were instituted in 1979 including recycling paper and displaying an energy consumption chart to awaken visitors to conservation. Reducing high voltage fixtures and limiting use of gas-powered equipment were additional energy-reducing changes. [28] In 1981 care was taken to reduce heat loss through the visitor center windows, to insulate hot water lines, and install an inter-burner for the furnace to make it more energy efficient. [29] As recently as 1985, the wood-burning stove in the maintenance shop achieved a 53 percent reduction of heating oil in comparison with 1975 use. [30] Operations were never seriously hampered by energy reduction; instead this program curtailed unnecessary energy use and increased energy conservation awareness among the staff.

Budget

The most obvious way in which the larger Federal government affects Whitman Mission is through the operating budget. Although this broad subject warrants indepth examination, a brief overview illustrates the fluctuating constraints within which Whitman Mission operates. During the park's early years, funds were scarce because of the excessive drain of World War II. Both Custodian Garth and Superintendent Weldon were always scraping money together for supplies. Weldon spent two years simply trying to get a fan. [31] Characteristically, he placed his predicament in historic and humorous perspective:

It reminds me of a letter Dr. Whitman wrote back to the Mission Board about 1839 saying they needed 220 additional missionaries and all supplies for them to help several scattered missions then established. The most he ever got from the Board was 13! [32]

Lack of funds was a major reason the park was not substantially improved or developed during the 1950s. However, Director Wirth's Mission 66 program provided funds for completing this development in 1964.

Associate Director William Everhart wrote in 1972, "The end of the Mission 66 program, in 1966, coincided with the escalation of the Vietnam war, and since that time nondefense agencies have taken budget cuts." [33] It was not unusual for Whitman Mission to operate under budget constraints; it operated under these cuts during the 1970s. Superintendent Kowalkowski wrote in 1978, "We struggled through the Zero Base Budget proposals for FY80." [34] Superintendent Amdor also faced inflationary budget cuts. In 1982 he compiled a long list of curtailed programs and cyclic maintenance to cope with "this year's double whammy of budget cuts and unfunded pay increases." [35] The staff presumably coped with the cuts because Superintendent Amdor wrote in 1985:

For the last two years we have intentionally not asked for any operating increases, but have gotten along quite well by using our own operating efficiency and improvements to make up the shortfall. We do not wish to be martyrs; in the future we hope the money saving effort does not backfire on the park or on resource preservation. [36]

Beginning in FY88, it appears that the park will operate under the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Deficit Reduction Act or a comparable package approved by Congress and the President. In anticipation of funding cuts the staff reduced its Equal Employment Opportunity recruitment trips, focusing on supporting local hiring instead. [37] The new entrance fee, authorized by Congress in 1986 and initiated at the park in September 1987, should reduce the impact of impending budget cuts. Despite the reduction, Superintendent Herrera is optimistic and foresees being able "to carry out all of the programs that we want to." [38]

RELATIONSHOP WITH LOCAL COMMUNITY

While management of Whitman Mission does not require support from the local Walla Walla and College Place communities, both the park and the townspeople benefit when each supports the other. Undoubtedly, such reasoning explains the high priority given to public relations during each administration. Public relations accomplishments appear in the Superintendent's Monthly Reports from 1941-1967 and again in the Annual Reports from 1972-1986. In fact, the August 1987 issue of the National Park Service Courier was devoted entirely to "friends associations," [39] an indication that community relations are still considered important servicewide. Most recently, the October 1987 operations evaluations encouraged the superintendent to maintain the Mission's close ties with the community.

Relationship with Local Organizations

The National Park Service was fortunate to have active friends associations to support the programs at Whitman Mission. The Mission support groups were unique in that they were formed without the request or assistance of the National Park Service. There was great community interest in the Whitman story, even before the National Park Service managed the site. Custodian Garth noticed this interest and remarked in his first Monthly Report that visitation was "not infrequent" in spite of the remoteness of the site. "This is evidence for the strong interest in the Whitmans which exists and which has existed for some time." [40] Therefore, the friends groups were vehicles for avid Marcus Whitman fans and for highly motivated, public-minded individuals; often one and the same.

The local people, remembers Custodian Garth, "got the site recognized as a National Monument; they were the motivators behind the whole thing." [41] Certainly, Herbert West was a motivator. He directed the park's first friends association--the Whitman Centennial, Inc., which donated the mission grounds to the U. S. government in 1936. Incorporated from 1936-1956, this group merged into another friends group--the Marcus Whitman Foundation.

The Marcus Whitman Foundation, 1950-1975, provided community leaders with the opportunity to help the National Park Service for 25 years. Although originally incorporated to raise funds for a Marcus Whitman statue for Statuary Hall, Washington, D. C., the organization was most active supporting the park's development program from 1950-1964. Superintendent Kennedy was a member and kept the others updated on the development progress. Other members, such as President Allen Reynolds, Howard Burgess, and Vance Orchard, wrote their congressmen about the park's boundary expansion, attended city council meetings to support the new entrance road and zoning regulations, and printed their support in the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Additional projects were spearheaded by Mrs. Goldie Rehberg, including raising money for the Marcus Whitman statue in 1953, and initiating a marker for Alice Clarissa Whitman, dedicated in 1968. After this flurry of Whitman-related activity, the group's focus shifted to the local historical society and the Mother Joseph statue for Statuary Hall. However, interest in the foundation was waning. There no longer seemed a need for the group since Marcus Whitman's statue was erected and park operations were running smoothly. Ex-President B. Loyal Smith remembers, "We didn't really have a purpose anymore." [42] Further, many original members such as Mrs. Rehberg had either left Walla Walla or died. Members tried to revitalize the organization in 1970 but, in 1975, under President Smith, the group disbanded. While the park lost a very beneficial support group, the Marcus Whitman Foundation was not the only organization that supported Whitman Mission. While service clubs are not technically "friends associations," many service clubs were indeed friends of the park.

The Kiwanis Club was an early supporter of the Whitman Mission, caring for the grounds in the early 1920s and 1930s. After the national park was established, the Kiwanis were not as active since the Marcus Whitman Foundation was, as Ex-President Allen Reynolds remembers, the park's main support group. [43] Even after the Foundation disbanded, Kiwanis participation was limited to guest lectures by park employees because "there was very little need of encouragement and support," says Bill Vollendorf, Club Historian. [44] However, in 1981, the Kiwanis, State Parks, State Department of Transportation, and the Whitman Mission placed a new "Waiilatpu" sign on Highway 12. [45]

The Daughters of the American Revolution also helped monument operations in its early years. Louise Jaussaud remembers giving tours of the archeological excavations for the 1947 dedication and helping raise money two or three times a year for the monument. [46] The DAR, like many other local groups, was interested in the park's development and visited the monument frequently during the 1950s and 1960s. In recent years, the DAR's closest connection with the Mission occurs when they attend the Memorial Day Service at the Great Grave. Current Regent Albina Kness feels that the Narcissa Prentiss chapter values Whitman Mission although they are not as active, anymore. "We're proud of what's out there," she said. [47]

Another group often mentioned in Superintendent Kennedy's annual reports was the Northwest Conservation League. They, too, supported the monument's development and arranged lectures and visits by Superintendent Kennedy and Historian Thompson. In fact, Mr. Thompson remembers many such community lectures:

I gave talks continually to all kinds of organizations in town: to the schools, to Whitman College, Walla Walla College, and service organizations of every stripe. We got along well with the Chamber of Commerce . . . . I thought we got along really well with the community. [48]

While these service clubs supported Whitman Mission, they were also committed to many other community service projects. Unlike these clubs, the Waiilatpu Historical Association, incorporated in 1964, was organized to serve only one agency: Whitman Mission.

The park's first cooperating association, the Waiilatpu Historical Association was organized: "to cooperate with the National Park Service in stimulating interest in educational activities and encouraging scientific investigation and research in the fields of History and Archeology." [49]

Cooperating associations developed early in National Park Service history to respond to visitor needs for inexpensive guides, maps, pictures, and other interpretive materials not available through Federal funds. Interested persons in nearby communities and educational institutions joined with park naturalists and historians to provide such items. [50] Accordingly, townsmen Vance Orchard, L. K. Jones, and Ralph Gohlman joined Superintendent Kennedy and Historian Jensen to form Whitman Mission's cooperating association. [51] Sales items were scarce that first year: Drury's First White Women Over the Rockies, Jones' The Great Command, Dick's Valient Vanguard plus two maps and one postcard. [52] Ten years later, the sales items included eleven books, six pamphlets, three maps, two slide sets and seven postcards. [53] Proceeds generated by the association expanded the park's interpretive program and library. During this 10-year span, townsmen L. K. Jones, Vance Orchard, Arthur Hawman, and Ralph Gohlman served intermittently as trustees; Gohlman for the duration. In 1974, the Waiilatpu Historical Association merged with the Pacific Northwest National Parks Association. Another expansion in 1975 included the U. S. Forest Service. In 1982 the name changed to Pacific Northwest National Parks and Forests Association. This expansion increased the association's ability to assist the park. Together with Walla Walla's Baker-Boyer Bank and the Welch Fund, the association sponsored the film, "A Memory Retrieved," about the dying craft of wagon-making. The association publishes the park newspaper, Waiilatpu Press, purchased the replica spinning wheel, and acquired the publishing rights to several out-of-print books such as Frazier's Stout-Hearted Seven. An outgrowth of joint community and park interest, the cooperating association provides an invaluable service to the interpretive program by expanding the visitor's opportunity to explore northwest history.

The existence of Whitman Mission's friends associations, cooperative association, and the service clubs indicates that citizens care about the commemoration of the mission site. However, organized support of the park was more prolific during the park's first 20 years than during its latter 20 years. This is due, in part, because there were highly motivated, enthusiastic people who believed in the significance of the Whitmans and were willing to become involved. More importantly, the mission was undeveloped and needed the help of groups like the Whitman Centennial, Inc., and the Marcus Whitman Foundation. After development was completed, enthusiastic individuals had no projects on which to exercise their talents. The lifeblood of every organization is the motivated individuals who initiate projects and oversee their completion. In recognition of this fact, park administrators compiled a list in 1966 of contributors and supporters of Whitman Mission and the National Park Service (see Appendix N). Thus, the individuals themselves, rather than the organizations per se, are the real friends of the park, then and today.

National Park Service Outreach Efforts

While many community groups and Marcus Whitman enthusiasts willingly supported Whitman Mission without any coaxing from the National Park Service, the park's outreach efforts also encouraged interest in the mission. Nothing was more effective for creating local interest and awareness of the park than the local newspaper. In fact, the 1960 master plan included the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin in its list of most important public relations contacts. [54]

Superintendent Weldon had a very good relationship with the Union-Bulletin's Jim Schick, who covered monument news during the 1950s. He printed stories about Marcus and Narcissa, the grounds improvements, displays, and visitation statistics. During the same time, Nard Jones, chief editorial writer with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, encouraged visitation with articles about the Whitmans and their commemoration by the National Park Service. In addition, the Union-Bulletin's roving reporter, Vance Orchard, covered park issues from 1951-1983. Thirty-two years of writing about the Whitman Mission instilled Orchard with a great interest in the park and its programs. Besides serving on the Marcus Whitman Foundation, the Waiilatpu Historical Association, and heading the publicity committee for the 1964 dedication, Orchard was master of ceremonies for the November 29 Memorial observance in 1980, and was one of the local experts consulted for the museum revision in 1987. Mr. Orchard said of his involvement:

History is a favorite subject of mine. The mission was part of my newsbeat for thirty-two years. If anything was discovered--an artifact or a letter--I wrote about it. I did have a special niche for the mission and what it represented. [55]

After 32 years of watching and helping the National Park Service manage the Whitman Mission and watching community reaction, Orchard feels that community interest has its "ups and downs," but that the support is there when the park needs it. "The program established by the National Park Service has been great over the years." [56]

The park had a high profile at times, due to extensive newspaper coverage. The 1940s was one such time, with the archeological discoveries providing newspaper copy that sparked community interest. The development phase was also a time of high profile. Favorable publicity was critical to the smooth completion of National Park Service plans so Superintendent Kennedy made every effort to cooperate with the Union-Bulletin. Reporter Orchard covered the development plans, helping the public understand these complex legal issues. His complimentary articles, combined with good planning and Mr. Kennedy's public relations skills, generated community awareness and support of the National Park Service. The quantity of newspaper articles about the new cultural demonstrations in the late 1970s and early 1980s indicates another period of high publicity. The most recent rash of publicity occurred in 1986, the Whitman Sesquicentennial year. While newspaper articles certainly contributed to public relations, the park's outreach efforts included more than just newspaper publicity.

During the park's formative years, the superintendents routinely lectured to service clubs and community groups. Custodian Garth and Superintendent Weldon talked to the Kiwanis Club and the Daughters of the American Revolution, reassuring these Whitman enthusiasts that major progress, while slow, was forthcoming. At one point Weldon remarked, "Perhaps they ought to have someone here who is more of a lawyer, good-will-among-the-public-maker etc. than I am!" [57] His successor, Superintendent Kennedy, was just that. Together with Historian Thompson, he lectured to groups and joined the Kiwanis and the Marcus Whitman Foundation to foster support for park development and increase respect for the National Park Service. The Monument's first three managers chose a highly participatory role in public relations because at Whitman Mission's tender stage of development, that was what was needed.

In later years, when public relations was not as critical to park operations, superintendents were not as personally involved with community relations. Instead, other park personnel, including the chief park interpreter, became more involved. For example, Superintendent Stickler took Kennedy's place in the Marcus Whitman Foundation and the Chamber of Commerce, while Chief Park Interpreter John Jensen joined the local planning committee for Fort Walla Walla city park. Although Superintendent Kowalkowski was a member of the Blue Mt. Federal Executive Association, Chief Park Interpreter Larry Waldron was president of the local toastmasters and on Walla Walla's Bicentennial committee. In this manner, the National Park Service did not so much advertise their programs as assist and participate in community-wide and community-generated projects. In recent years, Whitman Mission's booth at Walla Walla's Southeastern Washington Fair represents significant community contact. While Superintendent Amdor took an active personal interest in networking with community leaders, Superintendent Herrera is less interested in becoming involved. Thus, the amount of community involvement depends upon the park needs and the superintendent's priorities.

Although Whitman Mission is designated as a National Historic Site, its support tends to be local. Even visitation was distinctly local in the early years. Historian Thompson points out that the park was very remote and that, "there were no signs [on the old highway] to entice people to come in here." [58] Therefore, visitors were usually people already familiar with the Whitman Mission, often remembering the bare mission site, grave, and shaft from their childhood. It was not difficult for the National Park Service to gain their support for improving the site. Further, active park supporters during this time such as Herbert West, Chester Maxey, and Cameron Sherwood never doubted the relevancy or value of the Whitman story and were proud to help the National Park Service. Mr. Sherwood recently wrote on the occasion of the Sesquicentennial: "All those who are interested in the preservation of our historic sites are proud of the fine planning efforts which culminated in establishment of the Marcus Whitman Mission Site." [59]

The decline of this organized community support in the 1970s occurred partly because there was no obvious need for group support; witness the deorganization of the Marcus Whitman Foundation in 1975. Instead, the fledgling Fort Walla Walla Museum was in more pressing need of community help. Further, the Whitman story did not seem to inspire people as readily or easily as it had in the past, limiting the number of Whitman enthusiasts.

Currently community interest is demonstrated in somewhat different ways. The annual November 29 memorial observance and the Sons of the American Revolution Memorial Day service both invite community participation. Not surprisingly, the park's biggest supporters tend to be those people who remember its early years and have witnessed its growth--people like Bill Vollendorf, Gerwin Jones, and Vance Orchard. Or, as Chief Park Interpreter Dave McGinnis said in 1982, those people who "have developed fond memories of this place . . . " [60] Yet, the Sesquicentennial in 1986 provided an opportunity for people never before involved with the park to participate Wes and Sharon Colley, Gary Sirmon, and Pete Hanson are just some of the people recruited for the Sesquicentennial. By widening the support group in this manner, park administrators ensure that it will continue. While special events provide opportunities for short-term concentrated community participation, long-term participation occurs through visitation. Twenty-eight percent of visitors are from the surrounding areas. [61] These visitors often return again and again with out-of-town friends or relatives, while some regularly view the park's weekend movies. Again, many of these people remember the development years and return to see the progress. While community interaction is not as vital to park operations as it once was, it is nonetheless important. The Whitman Mission is public property and as such, the public continues to be an important administrative consideration. Since no better friends or more friendly critics can be found than in Walla Walla and College Place, this relationship with the Mission should be encouraged.

RELATIONSHIP WITH WHITMAN COLLEGE

The park's relationship with Whitman College deserves attention not only because both institutions share the same namesake, but more importantly, both contain extensive collections of information about Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and both institutions owe their existence to Whitman. While the relationship between Whitman Mission and Whitman College has not been consistent, it has nevertheless been a long one, beginning in 1859, when Reverend Cushing Eells established Whitman Seminary, "the fittest memorial" [62] for Marcus Whitman, on the site of the mission grounds. Although Whitman Seminary closed after 23 years of financial and enrollment problems, it reopened as Whitman College in 1882, at its present location in Walla Walla.

Struggling as it was for solvency in the 1880s, supporters of the college were not also necessarily supporters of the fledgling movement to erect a Marcus Whitman monument at the mission site. In fact, in 1888 a few town leaders briefly favored moving the victims' grave to Whitman College. [63] From the college's founding, then, it competed with the mission site for the right to be called the proper memorial to Marcus Whitman. One student criticized William H. Gray's monument campaign as misdirected:

It appears that greater honor could be done to the memory of Dr. Marcus Whitman than by investing $12,000 in a rock pile to be erected in the sage brush hills below Whitman station . . . . Let the name of Whitman go down to posterity coupled with education the cause in which the pioneer gave his life's blood. [64]

Undoubtedly criticism like this hurt the monument effort but despite such detractors and boasts that "Whitman College stands today as the only memorial of Marcus Whitman," [65] the shaft was indeed erected in 1897, with Whitman College noticeably represented at the dedication ceremony. The Whitman College student body, faculty, President Stephen B. L. Penrose, and the College trustees were all in attendance. [66] A December 1, 1897, Oregonian article explained that compromise prevailed between college and monument supporters between 1882 and 1897:

During the intervening years the conviction obtained in the minds of a few persons that, while Whitman College was and of right ought to be Dr. Whitman's true memorial, yet there ought to be a plain, comparatively inexpensive, yet enduring shaft to mark his resting place . . . [67]

|

| Proposed development site -- the base of Shaft Hill circa 1940.> |

The shaft was indeed plain and enduring, yet it was also not completely paid for. An outstanding debt of $2,500 existed several years after its placement near the mission site. Although Whitman College was solicited for funds, Mr. T. C. Elliott explained that the college had no responsibility for the debt:

It was definitely and positively understood, before Walla Walla parties had anything to do with the monument project, the Whitman College would not be connected in any way with it, and would not assume any responsibility in the matter. [68]

Although the college was under no obligation to pay the debt, in 1907 President Penrose joined a committee of four to liquidate the debt. [69] In this manner President Penrose demonstrated his support for memorializing Marcus Whitman at the mission site.

President Penrose recognized the historic and symbolic value of the mission site, so he brought his students to the mission grounds annually, an orientation still fondly remembered by former students. A Whitman College alumnus and national park supporter, B. Loyal Smith remembers his orientation as "one of my favorite memories in four years at Whitman College," [70] while the orientation trip inspired alumnus Nard Jones to write the book Marcus Whitman, The Great Command currently on sale at the park.

Although Penrose recognized the importance of the mission site, saving his struggling college was foremost in his mind. Therefore, he and others used Whitman's legacy to recruit funds and support for the college [71] while other groups cared for the mission grounds. After the end of his career, Ex-President Penrose became a trustee of the Whitman Centennial, Inc., supporting a Whitman National Monument just as he had the Whitman story his entire life.

Good relations between the college and the park continued in the 1940s, highlighted by the students' annual orientation trek. Mount Rainier Superintendent John Preston said in 1946, "Tom Garth has always maintained good relationship . . . with both Walla Walla College and Whitman."[72] The students were not the only college representatives to make the long trek to the mission; professors joined them, several of whom were park employees during the 1950s and 1960s. Professor of Biology Arthur Rempel was a summer seasonal ranger from 1953-1954 and on weekends and during the off-season in 1957 and 1960-1961. Kenneth Schilling, head of the music department, worked weekends in 1956 as a ranger-historian, as did William H. Bailey in 1957. Associate Professor of History Dr. Robert Whitner wrote the park's 1959 Interpretive Prospectus while Larry Dodd was a seasonal ranger from 1965-1969 before becoming curator of Whitman College's Eells Northwest Collection. College and park officials interacted at this time, also. In 1963, Whitman College President Chester Maxey wrote the interpretive theme statement for the new museum. Ex-National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth spoke at Whitman College's 1964 commencement and Whitman College President Louis Perry spoke at the mission's visitor center dedication ceremony the next day.

Use of Whitman College's research facilities, the Museum of Northwest History, and the Penrose Memorial Library, occurred intermittently. Custodian Garth and Dr. Melvin Jacobs, curator of the museum, exchanged information and material for displays and jointly investigated archeological sites along the Columbia River. [73] Superintendent Weldon tried to acquire artifacts from the Northwest History museum for display but met with little success. Weldon understood the college's position:

They feel, perhaps rightly so, that the articles at the college should be kept there in their museum at present until Park Service plans for a museum at Whitman National Monument are more definite of accomplishment. [74]

By the time the museum was built, artifacts from the mission, Fort Walla Walla, and the Evans collection in Spalding, Idaho, were placed on display, instead. It was not until 1970 that the Museum of Man and Nature loaned their Whitman-related artifacts to the park. Penrose Memorial Library was Custodian Garth's first research tool and is still useful to park historians such as Erwin Thompson. Many of the Whitman-related items from the college's Eells Northwest Collection and Archives are copied and located in the park's history and archival files. However, the park staff has not used the Eells Northwest and Archival resource materials much since 1969, "mainly because the [park's] research phase was over by the time I came here," explains Eells Northwest Curator Larry Dodd. "My guess would be that most of the staff, for the last ten or fifteen years at Whitman Mission, have very little knowledge of what's at Whitman College." [75] The most recent use of the material occurred this year when Superintendent Herrera asked Dodd to offer suggestions for revising the new museum and included him in the meeting of local Whitman authorities. Unfortunately his advice was not gleaned before the museum went into production, but as Dodd stated, "We've probably been asked more in the last week for things than we have for the last three or four years." [76]

Just as it is up to the individuals to use the Eells Northwest Collection, it is up to individuals to create and determine the type of relationship between the park and college. When students lost interest in the Whitmans during the late 1960s and their annual Penrose-inspired visit stopped, the college lost its principal reason and avenue for communicating with the Park. Larry Dodd explained that college officials were not about to push the students: "If [the students] are not going to be interested . . . why try to force feed them?" [77] The general apathy on campus concerning the Whitman story continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Today Whitman College students are not violently opposed to the Whitmans as they were during the 1960s; instead they know little or nothing about them and care even less. [78] The apathy is felt not just among students, but among college officials, as well. In 1975, President Robert Skotheim brought a tree from New York, Whitman's home state, and planted it in the park, but has paid scant attention to the Whitmans since. An intellectual historian and keenly sensitive to popular sentiment, Skotheim is much more comfortable talking about the long and beneficial Penrose adminstration than about the contributions of the Whitmans. [79]

Like community relations, interaction with the college exists only when a need arises. While most people of both institutions find little reason or ways to involve the other, other than for dedication ceremonies, some small strides are being made. The student orientation trip to the park was revived this year and, although it met with mixed reactions by both students and park staff, another trip next year is possible. Professor of History G. Thomas Edwards routinely escorts his Northwest History class to the park after reading Erwin Thompson's Shallow Grave at Waiilatpu. Again, the relationship depends on people. When people from both sides are willing to communicate, then the relationship will move away from the merely symbolic toward the substantive.

NEIGHBOR RELATIONS

Certainly, no one in the community has closer contact with Whitman Mission than the neighbors. This administration's relationship with the neighbors reflects how the park is perceived and predicts, to a certain extent, how successful its programs will be. Neighbor relations is a very subjective topic given that each party feels their point of view is justified whenever a debate or controversy arises. Although Whitman Mission's relationship with its neighbors has at times been rocky, overall, it has a good history. The following lists park neighbors and their approximate dates:

| 1940: | Enos B. Miller Ray Shelden Ella Coffin Howard Reser William C. Smith |

| 1953: | Glen Frazier Ray Shelden Ella Coffin Howard Reser Earl Smith |

| 1960: | Ray Shelden Ken Wasser Ella Coffin Howard Reser Earl Smith |

| 1975: | Neil Shelden Richard Bughi Molly Coffin Hanebut Howard Reser Marna Smith |

| 1987: | Neil Shelden Richard Bughi Molly Hanebut Yancey Reser Marna Smith |

An examination of Whitman Mission's neighbor relations history will be instructive to current administrators as they continue negotiating the same sensitive issues that have troubled managers since 1941.

Enos B. Miller

Of all the park neighbors, the relationship with Enos B. Miller is the most colorful. Miller lived just north of the park (his driveway was next to the Great Grave) from 1948-1953. Although he was a neighbor for a relatively short time, Custodian Garth and Superintendent Weldon both had their share of problems with Miller. He tested their public relations skills. The main issues included disputes over property lines, water and grazing rights, and Miller's right-of-way to his property. If it weren't for the import of these disputes, Miller's antics would be mere anecdotes. However, he raised water and grazing issues that are pertinent issues today.

Custodian Garth had his share of difficulties with Miller; perhaps more than his share. In 1949, Garth wrote a detailed memorandum to Superintendent Preston describing Miller's infractions, including destruction of government property (cutting trees), trespassing, and blocking the water from the irrigation ditch that served the millpond, particularly important since Marcus Whitman's grist mill timbers were visible under the water. Garth continued:

While I was working on the ditch Miller took two shots at me with his shot gun. The buckshot rattled all around me. Of course I was on his property at the time, but I had to be to repair the ditch. When I remonstrated with him, he again threatened me, saying he would shoot me anytime he saw fit. [80]

After referring this incident to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the United States Attorney in Spokane warned Miller that such conduct was intolerable; Garth was told to stay off Miller's property. [81]

Relations with Miller frustrated Superintendent Weldon, too. Miller claimed that neither the mission nor neighbor Ray Sheldon had any right to "his" water. As a result, water was frequently diverted back and forth between Miller's fields and the park. In response to sharing the water, Superintendent Weldon reported that Miller was "really up in the air about it and wants to know 'what the ----- there is to see at the monument anyhow!' " [82]

The park's northern boundary line jumped back and forth between Miller's place and the park almost as frequently as the water. Dr. Cowan, a local physician who held a controlling interest in the Miller farm, opposed the monument development and never accepted any of the boundary surveys. Several times Superintendent Weldon found the government boundary markers damaged or gone. Finally, he said of the whole subject, "I've just dropped the matter of a Miller boundary fence until the greater issue of land purchase is solved." [83] Thus, the real issue was that Miller had something the National Park Service wanted: land. Superintendent Weldon tried to foster good relations with Miller hoping he would be more amenable to selling his property. Therefore, in 1950, Weldon granted him a special use permit for grazing five head of cattle on the three-acre "church tract," located near the base of Shaft Hill. In addition to improving the appearance of this "unkempt weedpatch" that had "little historic significance," Weldon hoped to encourage friendly relations with Miller:

It is my opinion that if we can keep the good will between the Service and Mr. Miller which at this moment apparently exists . . . we will have a better chance of some day acquiring additional land from him. Granting a grazing permit will show that the Service can at times cooperate with individuals and that we are not trying to run Mr. Miller out of the farming business, a point he may have felt was true at times. [84]

Superintendent Weldon's plan only partly succeeded: Miller's cattle kept down the weed growth but the special use permit did not create goodwill between Miller and the park. [85] Miller discontinued the permit in 1952, the same year he was approached about selling 15 acres of his property. Miller insisted on selling all of his 90 acres or nothing. Since the Whitman National Monument was not authorized to buy one square foot of land in 1952, let alone ninety, negotiations halted almost before they began. The next year, 1953, Miller sold his farm, moved, and Superintendent Weldon breathed a sigh of relief. While the issues did not disappear with Miller, at least the confrontations ended.

While Miller certainly provoked arguments between himself and Custodian Garth and Superintendent Weldon, his complaints were based on a perceived threat to his farming operations. Whether the issue was water rights or access to his property, Miller felt threatened by the park and as a result, opposed its expansion and operation. Living next to the park, Miller tolerated several annoyances: visitors parking in his driveway, late-night parties near the Great Grave, and difficulty getting to his field on the east side of shaft hill. While neither Miller nor Weldon had an easy six years, they managed to coexist in spite of a difficult situation.

Glen Frazier

Superintendent Weldon was optimistic about future neighbor relations when the Fraziers bought Miller's farm in 1953. During Weldon's last three years Glenn Frazier cut grass from "the church tract" under a special use permit, similar to the arrangement with Miller. This permit was renewed each year until 1960.

Superintendent Kennedy had the responsibility of approaching the Fraziers about selling their land in 1956. The Fraziers were willing to sell, but their asking price was higher than park personnel thought the property was worth. As a result, Frazier's attorney and Assistant U. S. Attorney Ronald H. Hull spent the next two years haggling over price. Negotiations broke down in 1958 and the property was purchased as a result of public domain proceedings in 1960.

During the property negotiations, Superintendent Kennedy tried to keep friendly relations with Glen Frazier. The following 1958 memorandum from Kennedy to Regional Director Merriam is quoted in its entirety because, although amusing, more importantly it illustrates Kennedy's dedication to the Park Service.

You may recall that about a year ago the superintendent had trouble with Buster, Glen Frazier's Guernsey bull. Old Buster kept breaking out of the pasture and violating the sacred precincts of Whitman National Monument, much to the annoyance of the superintendent. So troubled was he one day by the presence of Buster that he most hurriedly climbed over the fence of the Great Grave to take refuge with the other Whitman victims while Buster ranted outside. The superintendent later had words with Glen but as usual, Glen did nothing.

A few days later . . . glancing toward the Great Grave he noticed that Buster was loose again and that there were visitors in that area. This was an intolerable situation . . . .

The superintendent drove over to the Frazier's yard, jumped out of the pickup, and started for the backdoor . . . [The Fraziers' dog] Stuffy heard the loud knocking. Waking from his slumber he came tearing around the corner, grabbed a bite of the superintendent's trousers and leg, and kept on going. Believe me, friendly neighborly relations were put to the breaking point then!

Glen came to the door and wanted to know what the trouble was. He was told. He was also told what would happen if that d--- bull was not kept out of the Monument . . . . He phoned his father, Lyle Frazier, and together the two that day repaired the fences and the bull, Buster, did not break out again . . . .

And just a couple of weeks ago Glen Frazier asked the superintendent if he had heard about Buster. It seems that Buster had begun to get a little mean and one day Glen mentioned to two of his cowboy friends that he was going to call a vet and have him dehorned. They said there was no need for that; they could do the job if Glen had a meat saw. Glen got a saw. The cowboys threw the bull. Then they tied a rope around his neck and feet and tied it to a tree. While one kept the line tight the other began to saw. For awhile Buster struggled and then seemed to give up. Glen, who was watching the work, looked at Old Buster and saw that he wasn't kicking any longer and told the men to hold up. Sure enough, the line around his neck was too tight and he had run out of air. So that was the end of the Frazier's bull. And in the hope that it would be remembered at the time of the negotiations for the Frazier's land, the superintendent shook Glen's hand and said it was sure too bad about Old Buster.

We superintendents will do most anything for our areas. [86]

Although the Frazier property negotiations were long and drawn-out, the National Park Service had the advantage all along. Although the specifics are explained in chapter four, it is evident that Kennedy had access to goad legal advice and was supported by all the resources the government could provide. When the National Park Service accepted Frazier's $44,000 offer, they acted on advice that a jury award would likely be higher. [87]

The Frazier property was essential to the park's development. Had it not been purchased, development could have been postponed for any number of years. Given its import, Superintendent Kennedy's eagerness to reach an agreement in whatever way possible is understandable. However, harmonious neighbor relations suffered because of his zeal to complete the Mission 66 development.

Molly Hanebut

Mrs. Hanebut's claim to the property adjacent to the park's east boundary, behind Shaft Hill, dates back almost as long as the Sheldens claim. Her grandfather Coffin settled the area in 1884 and her father built the house where she currently resides in 1911. At 85 years of age, Mrs. Hanebut remembers that in her childhood she attended Sunday school at the Whitman-Eells Memorial Church and that she and her classmates used to slide down Shaft Hill. Although they had fun, they always felt the shaft was special: "We never thought of going over that fence to that Monument; that was precious." [88] She remembers "there wasn't much done" until the National Park Service took over. "I think everybody has enjoyed it more . . . . Each man that has been there has been enthusiastic about it and it's a lot nicer." [89] Although Superintendent Kowalkowski remembered that "Mrs. Hanebut has been quite a vocal neighbor over the years," [90] and Superintendent Amdor remembered one disagreement that provoked her query, "What the ----- good are you?" [91] relations have mellowed with time. Mrs. Hanebut considers her relationship with the park good and is supportive of its programs.

Living alone, next to the park's remote east entrance, Mrs. Hanebut expressed concern about late night entrance-users. "I really don't think they should allow cars in that way . . . you never know what to expect." [92] Mrs. Hanebut's concern is worth noting given that this entrance is difficult for park personnel to monitor, far from the park residence. Although this walk-in entrance was initially opened for the convenience of College Place residents, it would be useful to reevaluate whether the shortened distance is worth the maintenance and policing difficulties, especially before the new entrance sign and landscaping is completed.

Ray and Neil Shelden

The Shelden family, Ray and his son Neil, claim the longest continuous relationship with the park of any family living next to Whitman Mission. The Sheldens' land claim dates to 1880 when Charles Swegle purchased the property from Montraville Fiske. [93] After Swegle died, the 640 acres was partitioned to his heirs in 1888 (see map, Appendix A). The Sheldens own the property west of the park, their claim resulting from May Swegle Dicus, formerly May Swegle Shelden. The other portion of the Swegle land is owned by the U. S. government (see map, Appendix O).

Given that the Sheldens lived on their farm before the national park was established, they have seen many changes in park operations. Neil Shelden has a keen sense of this past and many of his letters reflect his knowledge of park management precedents. For example, Shelden opposed Superintendent Amdor's attempt to run water down the Oxbow channel, because, he claimed, it contaminated his well and because "None of the previous National Park Service superintendents, since its origin in 1940, ever ponded water in the oxbow area." [94 ] Shelden is also aware that previous superintendents relied on his family, especially his father. Whether it was storage for Garth's archeological specimens or lending his tractor to Superintendent Weldon, Ray Shelden was often called upon to assist the park's basic operation. Thus, in recent controversies with Superintendent Amdor, Neil Shelden noted that, "It has certainly been convenient and speedy to call for the assistance of a tractor from the Sheldens those few times [y]our equipment has been stuck in the mud or ditch." [95]

The Sheldens, like most of us, are sensitive to change. Sharing a boundary line with the park, as they do, any changes at the park are evident. Oftentimes, whenever Ray or Neil felt a problem warranted the park staff's attention, it was due to some change that they perceived affected them. Both Ray and Neil wanted reassurance that any changes at the park would not harm their operations. For example, Neil submitted a copy of his income tax statement to Superintendent Kowalkowski and reiterated to him that, "Average estimated farm size for Walla Walla county is 650 acres--Sheldens 80 acres." [96] These actions reflect the same feelings of E. B. Miller almost thirty years ago: the park threatens his small farm. [97] Whether completely justified in their fear or not, the Sheldens' attitudes influenced their negotiations with the various superintendents over the two issues of principal concern: grazing rights and water rights.

Grazing

The basis for Sheldens' cattle grazing on Whitman Mission land predates government control of the property. From 1937-1941, Ray Shelden maintained the small, grassy area near the Great Grave and also after the Monument was established, during World War II, from 1943-1945. Shelden's cooperation was beneficial to both parties; in exchange for safeguarding the government's property during the war, Shelden was allowed to pasture his cattle on park grounds [98] even though grazing was prohibited in national parks at the time. [99] A formal special use permit was drafted the next year, 1944, for 50 head of cattle and 12 horses on the 37-acre tract south of the county road in exchange for Shelden performing "the duties of watchman . . . to see that no prowlers or marauders do damage to any of the monument area." [100]

After Superintendent Weldon's assignment to the monument in 1950, Shelden's caretaker services were no longer required. Instead, a new special use permit allowed Shelden to graze cattle for a $5.00 annual fee. [101] Mount Rainier Superintendent John Preston gave Shelden first chance for the permit because "Mr. Shelden has been a very cooperative neighbor at Whitman and should have first choice of the opportunity." [102] When Assistant Regional Director Herbert Maier questioned the nominal $5.00 fee, Superintendent Weldon based his defense upon Shelden's past cooperation:

I have the use of his tractor when needed for heavy hauling. We dig ditch, fix fences, weed control work etc. often together, Mr. Shelden giving of his time and services cheerfully. Because of the lack of equipment it is often found necessary to use some of his farm things and he mows the Mission Tract when needed in the summertime. All these things, though difficult to put a value on, really amount to considerable monetary value. [103]

Although the next year the cost of Shelden's permit rose to $97.50, the Forest Service rate, and his cattle reduced from 50 to 25, Superintendent Weldon established the precedent that Shelden's cooperation entitled him to special consideration, even if it was simply the opportunity to graze his cattle without having to bid for the privilege. Clearly, Weldon welcomed grazing, partly because cattle fit the historic scene and partly because cattle eliminated maintenance of the south pasture: "they maintain an area to the benefit and profit of the government which would otherwise be an unsightly area of obnoxious weeds . . . ." [104] Since grazing was convenient both for the National Park Service and the Sheldens, Ray and Neil pastured their cattle south of the mission site until 1983.

During the ensuing 33 years, the number of cattle, acres grazed, and cost of the special use permits varied (see Appendix Q). Each superintendent renewed Shelden's permit each year, negotiating price and acreage when necessary. Oftentimes, the conditions under which Shelden grazed his cattle depended as much on the personal perogative of the superintendent as it did on policy. For example, after 1964, Shelden's yearly fee for 20 cattle was $1.50 per animal unit month or $180.00 per year, figures based on the current Forest Service rate. However, in 1970, Superintendent Stickler reduced the permit cost from $180.00 annually, to $25.00 annually, because he placed great import on Shelden's aforementioned cooperation and his limited resources:

In my opinion, the permittee provides an excellent service to the government in maintaining the pastoral scene . . . . Considerable maintenance is necessary as spelled out in the permit and, in addition, the permittee puts his sprinkler system in operation during the dry season. The result is a much nicer appearing area than we would have if the pasture was not watered . . . .

We also enjoy other cooperation from the permittee and his family . . . . These include alerting us when potential poachers come into the area after the visitor center is closed. He also provides assistance with tractor and other farm equipment when we need it.

The small amount of revenue from the higher fee is inconsequential although quite important to a small farmer trying to scratch out a living on a few acres of land. [105]

Superintendent Stickler believed that Shelden deserved special consideration given his help and his financial concerns. He felt that fostering friendly and cooperative relations was more important than the grazing fee. By this decision, Stickler implied that the park was, in part, responsible for his farming operation. In sum, the National Park Service needed the south pasture maintained and both Superintendents Weldon and Stickler felt Ray Shelden was the best man, partly because of his proximity and partly because of the help he had given them. In addition, both Weldon and Stickler felt that Shelden's cooperation more than compensated for the small grazing fee.

Under the next administration, the Sheldon grazing issue became clouded because of staff error and second thoughts. In 1974, Superintendent Kowalkowski reexamined the special use permit he issued in 1972; his conclusions were very different from his predecessor. Based upon appraisals by the Washington State Cattlemen Association, the permittee, now Neil Shelden, owed $73.50 per year rather than $25.00. Current costs for grazing land stood at $5.00 per animal unit month making the Sheldens' fee $600.00; however, deducting maintenance costs resulted in the $73.50 figure. [106] Although Shelden agreed to the new price, new staff members failed to collect this revised fee and also failed to renew his permit. The entire situation was reviewed again, in 1978, and a new appraisal made by Reid Malin, Associate Appraiser from the Office of Quarters, Permits, and Utilities. Superintendent Kowalkowski agreed with the assessment that Shelden be held responsible for the previous three years and pay $73.50 for each year. [107] In addition, Malin advised Mr. Shelden that he could pasture more cattle but it would cost an additional $5.00 per animal unit month. Shelden agreed to the new stipulations although he implied that the new fee would be a hardship. [108] As a result, a special use permit was drawn up in 1980 for $294.00, Shelden's debt from 1977-1980. [109]

Clearly, it was Superintendent Kowalkowski's opinion that charging Shelden the "going rate" for his cattle was proper and fair regardless of the size of his farm or the cost of pasturing. Unlike Superintendent Stickler, he based his decision on policy and not on personal loyalty to the Sheldens.

Following Kowalkowski's lead, Superintendent Amdor took an even stricter approach toward the grazing issue. Utilizing both perogative and policy, Amdor chose to ignore Shelden's claims about financial difficulty and helping the park, and negotiate instead on the basis of National Park Service policy alone. As Shelden surely recognized, Superintendent Amdor deviated from the opinions and actions of past superintendents and followed his own course

In light of the fee-collection oversight from 1976-1980, Amdor took an aggressive stance in negotiations with Shelden. In fact, one of the park goals for fiscal year 1981 was to "maintain a proactive rather than reactive stand [with neighbors] on areas of mutual concern." [110] Therefore, Amdor quickly informed Shelden that another price change was likely: "the National Park Service will be evaluating the price element . . . ensure that an adequate sum is being charged per animal units of grazing." [111] Accordingly, he and Shelden negotiated the 1980 permit, the price of which was based on the land value rather than the number of cattle. This change was Shelden's suggestion:

I suggest we deviate from the norm and consider the pasture an individual land parcel--complete in itself. This approach would eliminate head count, simplify record keeping and free Park personnel for more productive work. [112]

This new permit also allowed Shelden to graze more cattle without the additional $5.00 per animal unit month and allowed him greater flexibility to rotate his cattle between the park's south pasture and his own. The resulting permit was valued eight percent of the tax assessed value of 28 acres, less any and all allowable amenities such as weed control and maintenance. [113] Again, Shelden agreed to the permit but maintained that the new price, $148.00 was too high. While Amdor acknowledged his concern, he remained firm that since the new fee was based on fair market value it would not place Shelden under undue hardship: "We are sorry that the permit costs for you have doubled, however we feel . . . our efforts to establish a fair and equitable method for determining the permit value were successful." [114]

Superintendent Amdor's principal concern was that the permit agree with other grazing practices in the area rather than agree with the precedent established at Whitman Mission. Amdor believed that Shelden's income and the cost of the special use permit were not related and should not be considered during negotiations: "One does not have anything to do with the other, they're all separate." [115]

Finally, the Sheldens' last special use permit was issued in 1983. The next year, in 1984, the park began implementing the Historic Property Leasing Program as directed by National Park Service Director Dickenson. [116] Under section 111 of the National Historic Preservation Act (16 U. S. C. 470 et seq) the National Park Service may lease historic properties and use the proceeds to maintain and preserve those properties. [117] Convinced that the south pasture was overgrazed, Superintendent Amdor exercised his right under the permit to have the pasture evaluated; he then placed it under the Historic Property Leasing Program. Neither Shelden's previously undisputed claim to graze the pasture nor his contention that the land was not overgrazed influenced Amdor. As a result, grazing bids were accepted in 1984, with David Corbett receiving the award. The park realized approximately $2,400.00 from this venture for the revegetation program recommended by the Oregon State University, Cooperative Park Study Program. [118] Thus, the park withdrew the 29 acres from the historic leasing program in 1986, and began revegetating. Acting Regional Director Briggle explained that the goal of the project

is to create a stable and historically appropriate vegetation covering . . . . The [Cooperative Park Study Unit] recommends that the new vegetation be firmly established before we allow animals on the land again. Thus we anticipate that the property will not be ready for a new lease until fiscal year 1989. [119]

The Sheldens, then, will not have another opportunity to graze cattle on the park's south pasture until 1988.

After examining 47 years of the grazing issue, clearly, the manner in which the Sheldens were treated and the provisions outlined in each permit depended upon each superintendent. Mr. Shelden agrees: "I assume each superintendent has the same job, job title, job description, but they can certainly handle it differently from each other." [120]

The Sheldens have dealt with seven superintendents, all with different personalities. "It's no different from any other neighbor as far as the varying personalities," says Neil Shelden. [121] Some chose to recognize the Sheldens' claims as valid, others did not. Custodian Garth and Superintendents Weldon and Stickler felt that Ray Shelden's relationship with the park warranted a lenient attitude toward the formal grazing requirements. Their attitudes were based on, and resulted in, a gentlemen's agreement rather than National Park Service policy. While this method of managing the south pasture ensured their cooperation, it resulted in a delicate management and public relations situation for Superintendents Kowalkowski and Amdor when they discovered the Sheldens had taken liberties with the special use permit. Not only did Superintendent Amdor monitor the grazing practices more carefully, he took a different management approach than his predecessors and dealt with the Sheldens in a strict business-like manner. Although Amdor tightened up on policy, he tended to blame the Sheldens for taking advantage of the superintendents when, in fact, the superintendents initiated the flexible grazing policy in order to benefit both the park and the Sheldens. Although strained neighbor relations were perhaps inevitable when Superintendent Amdor required full market value for the south pasture, in retrospect Shelden believes that "they have always given us a good price on the pasture." [122]

While the quality of relationship has, in the past, depended primarily on the superintendent, Shelden feels that there has been good long-term cooperation: "Over the forty years, with five superintendents, certainly the high majority were, I believe, favorable. I hope and assume that it was indeed mutual . . ." [123]

No doubt Superintendent Herrera's attitude will shape the next chapter in this park-neighbor relationship. Another issue that will very likely affect neighbor relations to a much greater extent is water rights.

Water Rights

A farmer's time-honored claim to his water--nothing is more important to his survival. Given that Whitman Mission is essentially a farm surrounded by other farms, disputes over water are inevitable. Particular sensitivity is required by park superintendents when negotiating rights that have been disputed intermittently since the park's inception. Unfortunately, the history of the 47-year old controversy is beyond the scope of this study. Instead, a brief mention of the issues will suffice to give park managers an indication of the import of water rights.

Like most issues, the water rights controversy began in the 1940s centering, then as now, on rights to Doan Creek. As already mentioned, neighbor E B. Miller complained about Superintendent Weldon diverting "his" water from Doan Creek for use at the Monument. In fact, neighbors Miller, Shelden, Harold Bowers, and the National Park Service all had legitimate claim to the water so a Doan Creek water use schedule was developed in 1952 for all four parties. [124] The schedule was updated in 1960 and 1962 for the park and neighbors Frazier, Shelden, and Ken Wasser.

In 1963 the watercourse changed when, as part of Mission 66, the park's irrigation ditch was relocated south of the Oregon Trail. Rights to Doan Creek's water is still the main point of contention. Whenever disputes arise, they usually include claims of unfair diversion or excessive usage of this water.

Since water for the downstream water users must flow through the park, maintaining the ditch, both on the grounds and before it enters the mission, is important. At least since 1950, all parties that benefitted from the water cooperated and periodically cleaned the ditch. [125] A formal agreement signed in 1963 stated that the park staff was responsible for keeping the ditch clean to ensure maximum flow to the neighbors. [126] Current neighbor Richard Bughi, who has lived near the park since 1971, explained that "several times a year we get together to work on the ditch," [127] at the point before it enters the park boundary. Indeed, Molly Hanebut, owner of this property, remembers that her principal business with the park concerned the overflow from this ditch:

They had to keep the ditch clean so that the water wouldn't overflow . . . . Having stock in a pasture, they're going to drink water wherever they can get to it . . . they stick their heads through and break the fence. Oh, my husband and I built so many fences it makes me sick to think about it. [128]

Although the ditch is cleaned each year, disputes still arise over which section of the ditch is the government's responsibility and which section is the neighbors' responsibility.

Of any controversy at Whitman Mission, the water rights is one of the most complicated and continuous, and of major concern to the neighbors. Bill Vollendorf of Walla Walla, an appraiser and park supporter, wrote a brief chronology of the controversy in 1984; an expanded water rights study would facilitate future management of this issue.

Most of the nearby farmers have been neighbors of the park for many years: current neighbors, the Sheldens and Mrs. Hanebut, had their farms before the park's establishment, while the "new kid on the block," Richard Bughi, has lived west of the park for 16 years. At the very least, when administrators understand the controversial issues involving the neighbors and how they have been managed in the past, chances are good that they can manage them fairly in the future.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

whmi/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2000