|

YELLOWSTONE

The History of the Construction of the Road System in Yellowstone National Park, 1872-1966 Historic Resource Study, Volume I |

|

|

Part One: The History of the Construction of the Road System in Yellowstone National Park, 1827-1966 and the History of the Grand Loop and the Entrance Roads |

CHAPTER V:

FROM WAGONS TO AUTOS 1912-1918

The 150 miles of road which the average park motor tour embraces are far superior to the dirt and macadam high ways found generally in the West.

Motoring Through Wonderland 1915

—Chester Davis

The question of the entrance of the automobile on the Park roads took on serious debate and examination by the Army, the Department of Interior, the transportation concessionaires, and the public in general. At the 1911 National Parks Conference held at the Canyon Hotel in Yellowstone National Park, the issue of automobiles in parks was discussed in a session called "Transportation in the Yellowstone National Park," facilitated F.J. Haynes, President of Monida & Yellowstone Stage Co. All three major transportation concessionaires in Yellowstone opposed the entrance of automobiles, but did support the idea of constructing a parallel road for automobiles. Haynes suggested the alternative of a self-propelled gasoline passenger rail which would provide access to all of the points of interest, connecting with the existing northern and western rail terminals. The cars, which would be equipped to handle all of the freight for Government and hotel needs, would eliminate the need for freight hauling over the existing road system. Haynes further stated that the Yellowstone Transportation Company and the Wylie Permanent Camping Company would be willing to "finance, construct, equip, and operate this proposed means of transportation" if it received approval from the Department of Interior. [194]

A lively discussion followed the talk in which the general feeling was not all-out opposition to the entry of automobiles on park roads, but that specific parks may not be as conducive to automobiles use as others. In fact, automobile roads were encouraged in some parks such as Glacier and Crater Lake. The following spring, the United States Senate called for an estimate of the cost of constructing new roads, or reconstructing the present system to accommodate the entry of automobiles and motorcycles without interfering with the existing method of transportation; vehicles drawn by horses or other animals.

Capt. C.H. Knight responded in May of 1912 with a lengthy document outlining the historical development and the existing condition of the road system, the improvements required to bring the road to a standard that would allow automobile traffic alongside the animal drawn vehicles, and a plan for a new road system that would only accommodate automobiles. The document covered in great detail the advantages and disadvantages of automobile traffic. The question was not whether or not to permit automobiles in Yellowstone National Park, but how they would be accommodated. The final analysis by the Army engineers was that the existing road system should be reconstructed to meet the needs of automobile traffic.

The three major transportation concessionaires, however, pushed for a separate road system for automobiles. They felt that the 2,000 horses used in the Park would never adjust to the automobiles, as they were on the open range for almost 8 months out of a year. Introduction of the automobile would cause runaways and accidents. The concessionaires were also worried about the investment they had in horses and equipment, and they were concerned about the hazards and delays that the two different forms of transportation would cause.

The Army included the solicited views of the transportation concessionaires in the report to the Senate. The Army's recommendation, however, called for the reconstruction of the existing road system at an approximate cost of $2,265,000. This single road system would accommodate automobiles, motorcycles, and animal-drawn vehicles. [195]

At the same time that Captain Knight was sending his report to Washington, road crews were fighting the almost annual Gardiner to Mammoth Hot Springs road landslides. During the middle of May, the soldiers kept the road open, but the warm days and the spring rains caused the Gardner River to rise. Fearing that the rising water would wash away the retaining walls and portions of the road, Lieutenant Colonel Brett requested approval to spend $500 on the repair of the old wagon road from the headquarters to Gardiner. The engineers felt the visitors would have no trouble reaching Mammoth Hot Springs if they used light vehicles. This wagon road was not one of the roads on which appropriated money was to be spent. [196]

The 4-1/2 miles of wagon road had been impassable for vehicles and it was considered unsafe for pack and saddle horses. A new 25-foot timber span bridge, with a 12-foot approach on each end, replaced an old wooden bridge on the route. Several other smaller bridges and 11 culverts were constructed of wood. Some sections were recorduroyed and boulders were removed by either blasting or excavation. The 4-1/2 miles of wagon road was widened and graded. [197]

The appropriations for 1912 and 1913 were increased appreciably over those of the previous six years, with the park receiving $177,33.34 and $200,000 respectively. The number of miles of sprinkling had increased to 100 with the plans for experimenting with road oiling during the 1914 fiscal year. Oil and water tanks were built at Mammoth Hot Springs for later use throughout the park. A 30-foot timber truss-bridge was built over Alum Creek and a number of other bridges were redecked and painted. Numerous bridges were replaced by culverts and many wooden culverts were replaced with metal ones. A new 650-foot retaining wall made of stone set in mortar was constructed on the Gardiner to Mammoth Hot Springs road. Additional stone replacement work was done through the Gibbon Canyon area and near the Virginia Cascades, on the Norris to Canyon road. A new 26-by-34-foot barn was completed at the Trout Creek road camp, a log storehouse was built at the east entrance, a log cabin/storehouse was built at the Lake sprinkler camp, and a 25-by-130-foot wagon shed with storage loft was finished at Mammoth Hot Springs. The location of the house at Mammoth Hot Springs was changed; plumbing fixtures were added to the outhouse at Mammoth Hot Springs; and the bunk house at headquarters got running water and washing fixtures. The Mud Geyser platform was rebuilt. [198]

The secretary of interior permitted automobiles to travel on the newly built road between Bozeman and Yellowstone [West Yellowstone] in 1913. However, the road was not in condition for automobile travel until 1914. The 17.86 miles of road that lay within the Park had forty seven bridges on it. [199] In January of 1914, the Gallatin County Commissioners appealed to Congressman John K. Evans for Government funds for the improvement of the 17 miles of the West Gallatin Road. As justification for the request, they claimed that the Park used the road for transporting supplies from the rail station at Yellowstone [West Yellowstone] to the Gallatin Soldier Station, that Yellowstone authorities used the road for other purposes in line with routine Park business, and that tourists used the road on their way to the West Entrance of the Park. The Gallatin County officials stated that they had already spent a total of $47,500 on the road, including $10,000 on the park section. They now estimated that they needed an additional $45,000 for improvements to the 17.8 miles of road, or about $2,500 per mile. [200]

The Army's response to Gallatin County's appeal was to not recommend funding for either improvements or maintenance. The Army said that the soldiers used the road "to some extent by park patrols, but it is not an absolute necessity." Most of the supply trains used the trails from Fort Yellowstone since the trail route was approximately 45 miles shorter than the road via the West Entrance. Since completion of the road, new trails had been built, some of which used the road. The Gallatin Soldier Station reported that only twenty-four parties (113 people) had used the road during the summer season of 1913. The Army felt that the cost of maintenance and improvements to the road could not be justified by the benefits gained. The Army's estimate for the annual maintenance requirements was approximately $3,000; they would not speculate on the cost of improvements, as the engineers had not inspected the road, but from their experience with similar roads, they felt it should have cost no more than $1,000 per mile. [201]

In June of 1914, Captain Knight, who was transferred to the Second Battalion of Engineers in Texas, was replaced by Maj. Amos Fries. [202] Up until the end of June, mostly routine maintenance was performed, with emphasis on upgrading the roads to make them safe for the passage of both animal-drawn and motorized vehicles. The road sprinkling covered 100 miles and some oiling was being tried. Three reinforced concrete bridges were built. One 40-foot reinforced-concrete arch bridge was built over the Firehole River near the Lone Star junction; a 40-foot span reinforced concrete bridge was built over the Gibbon River, 7 miles from Norris, and a 65-foot single-span, girder and slab constructed bridge was built over the Gibbon near the confluence with the Firehole River. A 40-foot steel arch bridge was built over the Gibbon near the Wylie Camp, 17 miles from the West Entrance; two 40-foot span wooden bridges were built over Pacific Creek, south of the Park in the forest reserve and a 10-foot reinforced concrete arch culvert was installed at Spring Creek.

Between the second and third mileposts on the Gardiner to Mammoth Hot Springs road, 120 feet of rubble-set-in-mortar retaining walls were constructed. The crews rebuilt retaining walls on the Mount Washburn Road, the Virginia Cascades section of the Canyon to Norris road, and in the Gibbon Canyon. The crews also built barns at the Gibbon Meadows and Grand Canyon road camps; cabins were built at the Beaver Lake and Grand Canyon road camps; and two "public-comfort houses" were built in the Norris Geyser Basin. [203]

In addition to the admittance of automobiles, in August of 1914, the acting superintendent sought unsuccessfully for permission to extend a spur of the Oregon Short Line Railroad into the park for 100 feet in order to facilitate the filling oil tanks that he wanted placed inside the Park. [204]

Major Fries instituted a new organizational plan for the road construction program by separating the Park into three divisions. Western Division under the supervision of William O. Fraesdorf, would cover the Gardiner to Yellowstone, the West Gallatin Montana Road, and from the junction of the Firehole and Madison River along the Firehole River to the Upper Geyser Basin. The Central Division, under O. R. Kroell, would cover from Tower Falls to the Snake River, from Canyon to Norris, and from West Thumb to the Upper Geyser Basin. The Eastern Division under R. D. Rader, would cover the road through the forest reserve to the road junction at Lake. In August of 1915, a new Northern Division was created under the supervision of Capt. John W. N. Schultz.

Another change Major Fries instituted was in the earth loosening and hauling procedures. He found that the most economical way to loosen the earth and gravel was by plow, employing scrapers to haul it; he found that the most desirable mixture for the road surface was a mixture of one third clay and two thirds sand. Major Fries instructed the crews to use material from the side of the roads for temporary repairs unless they were finished roads that were completely macadamized, in which case gravel or broken stone was to be used. He felt that the hauling of gravel or sand for long distances was about as "nonsensical as patching cotton clothes with fine silk." [205] His approach to filling ruts or chuck holes on macadamized roads was to first clean out the hole and scratch the surface to facilitate a bond with the new material. The fill material had to be screened gravel or rock bound with clay or stone dust so that after watering, the repair would wear as well as the macadamized road. Fries ordered the construction of ditches to be 3-1/2 feet on either side of the 18-foot wide standardized road. Hillside ditches were to have drains not more than 100 feet apart and they were to be as wide and deep as possible. Fries said that to a good road man, "A road without ditches looks as natural as a man's face without a nose." Fries called for the templates to be tried at certain sections of the road and for the road to be "brought to proper crown."

Fries who ran a "tight ship," felt "the best workman is the one that can do first class work at the lowest cost." He was very strict on the workmen's output, expecting that a day's work was eight hours, with no exceptions for going to or from work or for lunch. [206]

By the spring of 1915, other improvements to the facilities had been finished. Telephones had been installed at the engineers camps and at most of the other road camps scattered throughout the Park. A covered rack for the storage of reinforcement steel used in the concrete bridges and culverts, and a steel and concrete gasoline storage tank, with a capacity of one carload, were built at Mammoth Hot Springs. Two concrete tanks, each with a capacity of holding two carloads of oil, were built, one at Gardiner and one at Yellowstone, Montana.

Sprinkling continued on 112 miles of roads and oiling was tried on two sections of park roads. In 1915, the engineers planned to use a finish of 90 percent asphalt oil and broken stone. The least expensive of the two brands scheduled for use cost 2.1 cents per gallon at San Francisco, with a freight cost of 4.5 cents to Yellowstone, Montana, plus an additional 6 cents per gallon freight cost for 50 miles within the Park. Thus, in order to save some cost per mile, the Army continued to push for the construction of two lengths of rails or 66 feet of rails to be built adjacent to the rail station in Yellowstone, Montana, to just inside the Yellowstone boundary. Prior to receiving permission, the Army planned to build a pit just inside of the Yellowstone boundary. With certain restrictions, such as the restriction of the engine to come into the Park, the construction of an obstruction which would prevent cars from coming into the Park without Army supervision, and the understanding that the track could be removed at the Department of Interior's request, permission was granted in May 1915. [207]

Following earlier decisions, only concrete bridges were being built for use on the Belt Line and steel bridges with concrete floors were used in the forest reserves. Red spruce was the preferred material for abutment sills on the wooden bridges. For economic reasons, all of the concrete bridges were built by day labor. If a span of 10 feet or less were needed to be bridged, a culvert was installed. If more than 10 feet, it was spanned by a bridge.

Major Fries believed the practice of building bunk houses and barns at road camps was not practical. He felt that for them to be effective required placing them in locations that would offset the long commutes the crews had to make which were too costly. He preferred the use of 16-by-24-foot tents. [208]

On August 1, 1915, the first automobiles were allowed into the park producing both positive and negative effects. During the dry and dusty season, the heavy touring cars and light, high-speed trucks were harmful to the road surface. However, during the wet season, use of these vehicles had the opposite effect. Besides the cars being easier on the roads, their pneumatic tires had a decided ironing effect. The slower speed, heavier trucks with solid tires had a negative effect on the road, especially during the wet weather when their chained tires cut deep ruts into the surface. Thirteen trucks replaced most of the 6 and 8-horse teams, which were very detrimental to the Park roads because of their practice of following the same ruts.

A 5-ton White truck, purchased in 1915, greatly reduced the cost of hauling in the park. It immediately became the "workhorse of the park" by operating 16 hours a day, for use in plowing, grading, dragging, and hauling. [209] The Army engineers felt that in order to achieve a reasonable per-mile cost for construction and improvements, sufficient money should be spent on necessary equipment. [210]

With 3,445 automobiles entering the Park between June 15 and September 30, 1916, Yellowstone advanced into a new era of tourism. A couple of years earlier, the Park began planning for increased visitation due to World War I and the expositions in San Francisco and San Diego. The newly formed Park-to-Park Highway Association which met at the Canyon Hotel in Yellowstone, focused the attention of other such clubs and government officials on the opportunities of traveling to the national parks on a connecting system.

Regular routine maintenance and improvements were carried on during 1916. The major road problem was correcting the continual slide problem on the Gardiner-Mammoth Hot Springs road. Slides had occurred over a number of years, and in 1915 much work was done and the road was considered to be in good shape. However, during the summer and winter of 1915, slides reduced the road width to 10 feet and new slides developed several hundred yards closer to Gardiner. Slumping at the new slide caused the road to be closed several times during the fall of 1915 and four times during the spring of 1916. Blasting and grading prepared the road for the tourists in 1916, but the blasting and high water in spring caused the sections of retaining wall to give way and/or weaken. [211]

As a result of the increased automobile travel to the Park via the West Entrance, the Army engineers reversed their opinion regarding government funding for improvements to the 17.8 miles of the West Gallatin Road. In the 1916 Annual Report, Major Fries requested that the government assume the responsibility for the maintenance and repair of the 17.8-mile section. [212]

On August 25, 1916, the National Park Service was created, but the military would continue to have a presence in the Park until 1918. A civilian, Chester Lindsley, was appointed the "supervisor" and remained the administrator of the Park until Horace Albright was appointed superintendent on June 28, 1919. Many of the discharged cavalry soldiers remained in the Park either as rangers or in the maintenance department.

The following year, improvements to the approach roads and important realignments to the Belt Line were made. Robert McKay of the Buffalo Mining Company, who had mining interests in the Cooke City area, continued with improvements and repairs to the Cooke City road. During the previous year, McKay had made great improvements to the road by cutting out four hills with dangerous curves, accomplishing some realignment, providing light graveling to some sections, and building a 30-foot span bridge, with gravel-filled log cribbing approaches totally 100 feet across Pebble Creek. [213]

After more trouble with the slide area on the Gardiner and Mammoth Hot Springs road, the engineers finally decided that perhaps a relocation of the road across the river, which would be very expensive, or rebuilding the old freight road would be the answer.

The United States' entry into World War I in April, 1917, hastened the transfer of road responsibility to the newly created National Park Service. By July, when Colonel Fries was transferred to France and Capt. John Schultz assumed the responsibility of the road work. Over engineers over road damage and maintenance responsibilities. The concessionaires were operating under new contracts, which compelled "them to pay, as for consideration for their privileges, on a schedule of charges that will bring in, at the close of the season, a very large sum of money which will be used in administrating the park." [214] Prior to his leaving Yellowstone, Fries wrote to Horace Albright advising him of the problems stating, "The Transportation Company doesn't seem to appreciate that everything they have in the world came from the roads and that all the fortunes they expect to make in the future will come from the same place so that instead of cooperating and letting us have transportation at reasonable rates when we want to rush men to fix bad places often caused by their shoveling out the snow and then driving heavy cars continually in one track, they sting us the limit for every man and piece of material hauled for us." [215]

In October of 1917, Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane inspected the road system in Yellowstone National Park. While visiting the Park, Lane made a number of suggestions for improvement, including a request for a painted white or whitewashed railing at a point 7.1 miles from West Thumb, construction of preferably stone guard rails at dangerous points between Chittenden Bridge on Upper Falls (heavy pole rails painted white would have been his alternative), and grading the slopes to the inside bank at a point where the road approached Dunraven Pass from Canyon. At Gibbon Canyon, he recognized a safety and a visual problem, with the growth of small trees since the road was built. He found the trees obstructed the view of the river and in turn made for dangerous driving. He also felt that the removal of a few trees at the Gibbon Falls would "afford a better view of the falls." [216]

A few months earlier, an assessment of the road conditions was compiled. However, funds were running out, so Captain Schultz advised Lindsley that some of that work would have to be completed the next season. [217]

As a result of the creation of an agency to administer all of the national parks and national monuments, many organizational changes would be made in Yellowstone. During 1917, more attention was given to road work by the newly created agency. In fact, prior to Secretary Lane's visit to Yellowstone, he had written a letter to the secretary of war proposing that the Department of Interior should take over the road work in both Yellowstone and Crater Lake National Parks. Horace Albright, assistant to the National Park Service Director Stephen Mather, shared similar feelings and in a letter to Franklin Lane wrote:

I do not know what can be done about it now, but one thing is certain, we can not make the national parks the place for the engineers to get their road building education. We need trained road builders in the parks, not inexperienced West Point graduates who go there to learn this branch of engineering and control the thing at the same time. The Yellowstone now has the worst roads of any national park, except Rocky Mountain where we have nothing to do with the improvement work, and now is the time that we must do something. [218]

The last supervising Army Corps of Engineers officer in the park, Maj. George E. Verrill supervised the road work until June 30, 1918. Prior to his departure, routine maintenance and improvements were carried out. Crews worked continually trying to keep the Gardiner-Mammoth Hot Springs road open throughout the summer of 1917, but the spring thaw of 1918 caused extensive movement in the slide area and high water in June resulted in the complete destruction of a one-mile section of the road. The engineers were forced to abandon the road and make improvements on the old freight road until the main road could be reconstructed.

High water in June played havoc in a number of other locations in the Park. Road sections at the Snake River and Pilgrim Creek bridges in the southern part of the Park and in the forest reserve were damaged. Road sections and bridge approaches were damaged on the Cody Road. On the Cooke City Road, the Lamar River, the Pelican Creek, and the Soda Butte Creek bridges were washed away. Because this road was not heavily traveled by tourists, the Park did not initiate immediate repairs. Using some materials supplied by the engineers, private citizens from Cooke City built a cableway over the Lamar River to convey supplies and people.

By the time the Army left the Park, all of the significant wonders or scenic areas were accessible by motor-drawn vehicles and all of the entrances were open to travel. There were no serious problems on the 137-mile Grand Loop, other than a worn foundation and lack of original surfacing material. The entire system needed to be macadamized or graveled. As stated earlier, the north approach road had been washed out and the only entrance was via the old freight road which was muddy and slippery during wet weather. Of the 13-1/2 miles on the west approach road, 9-1/2 had been macadamized. Five of the 9-1/2 miles were considered in excellent condition, with a macadam surface covering an 18-foot width; the remainder had a macadamized width of 10 feet. All but 2 miles of the 23-mile south approach road had been widened and graded, and with the exception of the June high water damage, it was considered to be in good condition. For the past few years, the only work done on the forest reserve road was the 30-mile section just south of Yellowstone. Little work had been done on the section south of the Moran Post Office. The 26-mile East approach road was considered to be in fair to good condition, but the 28 miles through the forest reserve was heavily damaged by the high June water. Prior to that time, the road was considered to be in good condition. Other than the June damage, the Cooke City Road was considered to be in good condition. The Bunsen Peak, Artist Point and Inspiration Point roads were considered to be in good condition. The road through the Mammoth Hot Springs terraces was considered to be in poor condition for motor-drawn vehicles and fair condition for horse-drawn or foot traffic. The bridges were considered to be in good condition, with the exception of a wooden bridge over the Firehole (.6-mile southeast of Old Faithful Inn), a wooden bridge across the Gibbon at Norris, two wooden bridges near Canyon Hotel and a wooden bridge across the Blacktail Creek, plus a number of bridges in the forest reserve. [219] Stephen Mather viewed the later years of the Army Corps' direction of the road work as years with "entire lack of a comprehensive policy which considered the popular uses of the Park, and in later years, the failure to give any degree of permanency to the organization of the engineering force. Engineer officers were detailed to the park for short periods of time, then replaced by others, who often came with different ideas from their predecessors; there was constant altering, modifying, and changing of plans for improvement work and of methods of performing this work." [220] Mather thought the new combined management of Yellowstone under one department and one park supervisor or superintendent would eliminate the double, and in some cases, triplicate effort. For the past two years, the Park had a superintendent who reported to the secretary of interior, a district engineer who reported to the chief of engineers of the Army, and commanding officer of the troops, in charge of protection of the Park, who reported to the Western Military Department in San Francisco. During 1918, the assorted offices were combined and the former Engineers' Building became the park headquarters. [221]

In May of 1918, Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane, issued a Statement of Policy in which road construction and improvements were specifically addressed:

In the construction of roads, trails, buildings, and other improvements, particular attention must be devoted always to the harmonizing of these improvements with the landscape. This is a most important item in our program of development and requires the employment of trained engineers who either possess a knowledge of landscape architecture or have a proper appreciation of the aesthetic value of park lands. All improvements will be carried out in accordance with a preconceived plan developed with special reference to the preservation of the landscape, and comprehensive plans for future development of the national parks on an adequate scale will be prepared as funds are available for this purpose. [222]

The philosophy expressed by Franklin Lane is reminiscent of those expressed by Captains Kingman and Chittenden of the Army Corps of Engineers.

|

|

Mount Washburn Road, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Completed Paved Road near West Entrance, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Spring Creek Road Camp, September 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

DeLacy Creek Road Camp, September 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Enoch's Road Camp at Cub Creek, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Trail Creek Road Camp, Army Corps of Engineers, 1913 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gravel Pit, 6 Miles from West Entrance, 1915 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gravel Screen, 9 Miles from Canyon, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Otter Creek Gravel Pit, United States Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Supply Tank and Sprinklers near Brickyard, September, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Oil Pit at West Yellowstone Camp, United States Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Oiling Road Two Miles from West Entrance, 1915 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

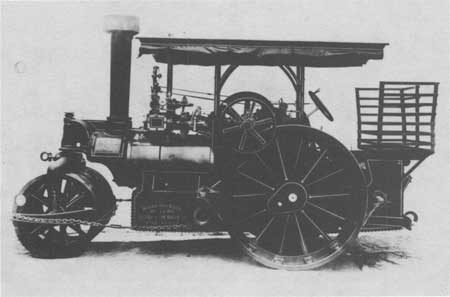

Steam Roller Purchased by Army Engineers in 1916 for West Yellowstone Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

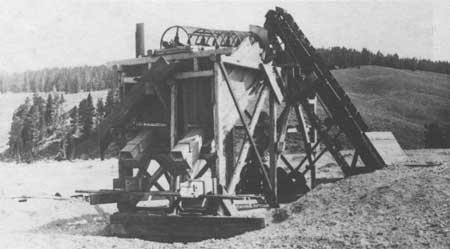

Rock Crusher, September, 1914 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Culvert and Ditch Construction on Cooke City Road, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

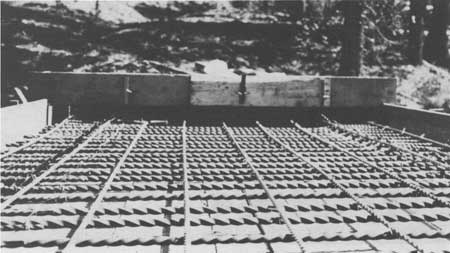

Culverts on Continental Divide Showing Steel Reinforcement, 1915 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

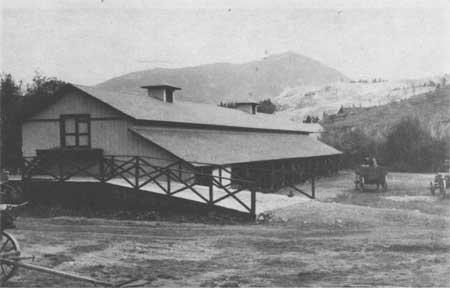

Barn, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

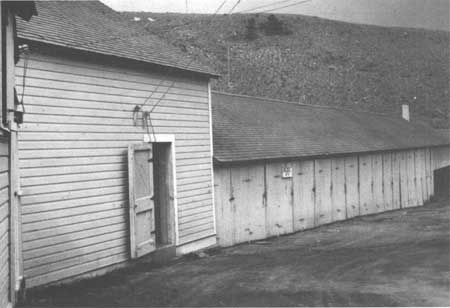

Coal Shed and Barn, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Shed, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

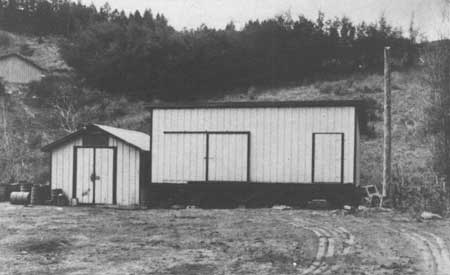

Bunkhouse and Shops, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Cottage, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Old and New Engineers' Quarters at Mammoth Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Engineering Deparment Barn, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Wagon Shed, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Shed, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Garage, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gasoline Tank House, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Auto Supply Building, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

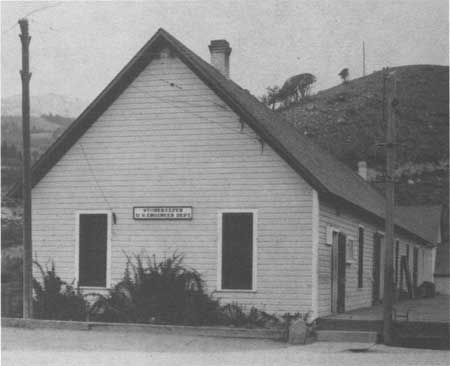

Storekeeper Building, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Mess Hall and Former Residence of Hiram Chittenden, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Commissary, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Supervisor's Office, 1917, United States Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

CHAPTER V:

ENDNOTES

194. J.F. Haynes, "Transportation in the Yellowstone National Park," Proceedings of the National Park Conference held at the Yellowstone National Park September 11 and 12, 1911 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912).

195. New Roads in Yellowstone National Park, Acting Secretary of War transmitting information in response to Senate Resolution of April 2, 1912, relative to the cost of construction of new roads in the Yellowstone National Park, Sixty-second Congress, Twenty-fourth Session Senate Document No. 871 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 3, 14, 15, and 16.

196. Lt. Col. L. M. Brett to Secretary of the Interior 14 May 1912 and 20 May 1912. In addition to the problems caused by the natural conditions, the Yellowstone Transportation Company wagons hauling coal "shook the road at the dangerous and narrow part that a section of it fell into the river, leaving a roadway of only about 3 feet in width for a distance of 12 feet." Lt. Col. L. M. Brett to Mr. H. W. Child May 2, 1912. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

197. Brett to Secretary of Interior, 22 June 1912. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

198. Capt. C. H. Knight, Maj. J. B. Cavanaugh, and Maj. Jerry J. Morrow, Report Upon the Construction, Repair, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park; Report Upon the Road Into Mount Rainier National Park; and Report Upon Crater Lake National Park, Appendices EEE and FFF (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1913), 3,268-3,270.

199. E.H. Schumacher, County Clerk of the Board of Commissioners, Gallatin County, Montana, to Maj. E. S. Wright, 12 March 1913. The District Engineers Office, Yellowstone National Park to Chief of Engineers, U. S. Army, 16 February 1914. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

200. Charles Waterman, Commissioners of Gallatin County, Montana, to Honorable John K. Evans. Schumacher to Lt. Col. L.M. Brett, 6 February 1914. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

201. District Engineer Officer, Yellowstone National Park to Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 16 February 1914. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

202. Special Orders No. 181, War Department, June 5, 1914.

203. Maj. Amos A. Fries and Maj. Jay J. Morrow, Report Upon the Construction, Repair, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park; and Report Upon Crater Lake National Park, Appendices EEE and FFF (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1914), 3,393-3,395.

204. Acting Superintendent to Secretary of the Interior, 5 August 1914. Assistant Secretary of the Interior to Acting Superintendent, 6 August 1914. (telegram) Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

205. Fries, Yellowstone Park Road Work, August 11, 1914.

206. Fries, Yellowstone Park Road Work. See Appendix for the "Rules and Regulations for the Work of the Engineering Department in Yellowstone National Park," May 4, 1915.

207. Fries to Secretary of the Interior, 10 May 1915. Stephen T. Mather, Assistant Secretary of the Interior to Col. L. M. Brett, 26 May 1915. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

208. Maj. Amos A. Fries, Report Upon the Construction, Repair, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1915) 3,753-3,765.

209. Maj. Amos A. Fries, Report Upon the Construction, Repair, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park, and Report Upon Crater Lake National Park (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1916), 3,626-3,627.

210. Henry Breckenridge, Acting Secretary of War to Chairman of Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives, 15 January 1916. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

211. Fries and Williams, Report Upon . . . . Yellowstone National Park 1916, 3631.

213. Maj. Amos A. Fries and George Zimn, Report Upon the Construction, Repair, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park for 1917 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1917), 3,633.

214. Horace Albright, Acting Director of the National Park Service to Major Fries, 7 May 1917. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

215. Fries to Albright, 14 July 1917. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

216. Chester Lindsley, Office of the Supervisor, Yellowstone National Park to Captain John Schulz, 9 October 1917. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

217. Road Improvements; July 1917:

Road through Gardner Canyon narrow at points and subject to slide, which is very dangerous.

Bridges between Mammoth and Gardiner are about 9" below road bed. Very hard on auto springs, both going onto and off of these bridges.

Road over the Mammoth terraces unfit for auto traffic. Should be improved and made safe by June 20th.

Road around Bunsen Peak unsafe for autos. Small expense to repair.

On top of hill on main road two miles from Mammoth a number of very bad and hard rolls and bumps.

Two serious holes more than half way across Swan Lake Flats.

Road up Glen Creek toward Electric Peak could be made passable for quite a way at very little expense, to enable parties to get that far and then to walk to the mountain.

Bridges at Upper Gardner River, Willow Creek and Gibbon River at Norris, below and above road levels.

Road at Roaring Mountain in poor shape.

Deep holes at many of the sprinkling tank filling stations throughout the entire park.

Road Norris to Fountain down the Gibbon Canyon very rough, full of large chuck holes and broken culverts. Also contains one or two improvised log bridges where culverts have been washed out.

Wylie Gibbon Camp over mesa road to Firehole River, about four very bad chuck holes that could be filled with little expense. This road will be used all next summer and should be repaired.

On the flat 1 mile before Fountain Hotel road very rough.

Road to Firehole Lake, Great Fountain Geyser, impassable for automobiles. Repair automobile schedule routed this way. Should be fixed before June 20th. Small expense.

Very deep hole across entire road just before reaching Excelsior Geyser.

Road to Biscuit Basin and Morning Glory springs in no shape for automobiles. All travel is to be routed this way. Immediate necessity of being repaired.

Most of the platforms at points like Paint Pots, Excelsior Geyser, Keplers Cascades, etc., throughout the entire park are too high for automobile passengers to alight from their machines onto the platforms. They should be lowered to correspond to the platform at Apollinaris Spring.

Upper Basin to Thumb, seven to eight mile post, road very narrow and deep wash close to bank, so cars have to travel on the outside.

Number of very dangerous holes on the other side of Continental Divide, also after crossing the Divide and going down the hill toward the Thumb of Lake.

After crossing Divide between Thumb and Lake on the tip of the hill down to the five mile post, the road is very rocky and had severe holes. This is the place that the private machine tipped off the road last summer.

Lake to canyon road should be routed via Sulphur Mountain from Trout Creek. Sulphur Mountain is very interesting and should be shown to the passengers. This road is not more that a mile or so longer than the present road. There is an old road going this way which is in very good condition and could be traveled if one or two culverts are replaced. This take one farther into Hayden Valley, where elk are very often seen.

Bridge across Alum Creek a foot below the road bed and about 4 inches above the water level.

Road along the Yellowstone, between three and two mile post very narrow. Two or three very bad holes.

Road along the Yellowstone at the rapids and upper falls very narrow and dangerous. Heavy guard rail should be placed along there.

Approach to the concrete bridge from the opposite side of Yellowstone River in very bad condition. Dangerous for the operation to the camps next summer.

Going from Canyon toward Dunraven Pass along the hillside half a mile before reaching the entrance of Dunraven pass, the road should be graded to slope toward the bank and logs should be imbedded along the outer edge of the entire road from this point for about a mile.

Road over top of Mt. Washburn should be cleared of rocks, small and large. It is very difficult for a large car to go up there at the present time and extremely hard on tires, as the road is practically covered for miles at a time with sharp stones which have blown onto it.

The last three miles before reaching Tower Falls the road is very rough and narrow and worn. Two or three severe chuck holes.

More than half way up the long hill from the Tower Falls Soldier Station to the top of the cut, there are several very bad holes and bumps.

Road down Blacktail Creek back of Mount Everts could be fixed with little expense, for the benefit of fishing parties.

This list provides a very good overview of the conditions of the road system in 1917.

Capt. John Schulz to Chester Lindsley, 11 October 1917. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

218. Horace Albright, Acting Director, National Park Service to Franklin Lane, Secretary of the Interior, 17 October 1917. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

219. Maj. G.E. Verrill and Col. George Zuin, Report Upon the Construction, Repair, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park; Report Upon the Road Into Mount Rainier National Park; and Report Upon Crater Lake National Park Appendices EEE and FFF (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 1977-80.

220. Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1918 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 39-40.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs-roads/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 20-Apr-2016