|

YELLOWSTONE

Geysers of the Yellowstone National Park |

|

THE YELLOWSTONE "GEYSERLAND."

The wonderful variety, the great number, and the large size of the geysers of America, found in the Yellowstone National Park, demand a somewhat longer account of this region. The geysers are found in detached groups, occupying basins or valleys of the great table-land which forms the central portion of the park, a region whose heavy forests and uninviting aspect, combined with the rugged nature of the encircling mountain ranges, so long proved a barrier to exploration, even to those adventurous trappers and prospectors of the Great West.

|

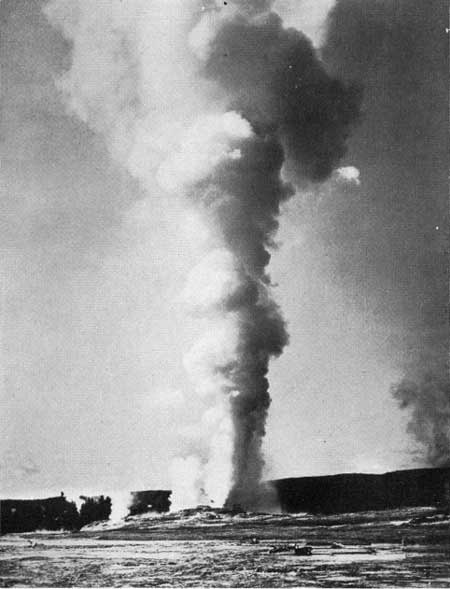

| GIANT GEYSER. Photograph by F. J. Haynes. |

The geyser "basins," as the localities are termed, conform, in their relations to the surrounding high ground and their coincidence with lines of drainage and the loci of springs, to the laws governing the distribution of the same phenomena in other parts of the world. The park itself is a reservation of about 3,500 square miles, the central portion being an elevated volcanic plateau, accentuated by deep and narrow canyons and broad, gentle eminences and surrounded by high and rugged mountain ranges. This central portion, whose average elevation is about 8,000 feet above the sea, embraces all the hot-spring and geyser areas of the park. The volcanic activity that resulted in the formation of the park plateau may be considered as extinct, nor are there any evidences of fresh lava flows. Yet the hot springs so widely distributed over the plateau are convincing evidence of the presence of underground heat. There is no doubt that the waters derive their high temperature from the heated rocks below, and that the origin of the heat is in some way associated with the source of volcanic energy.

|

|

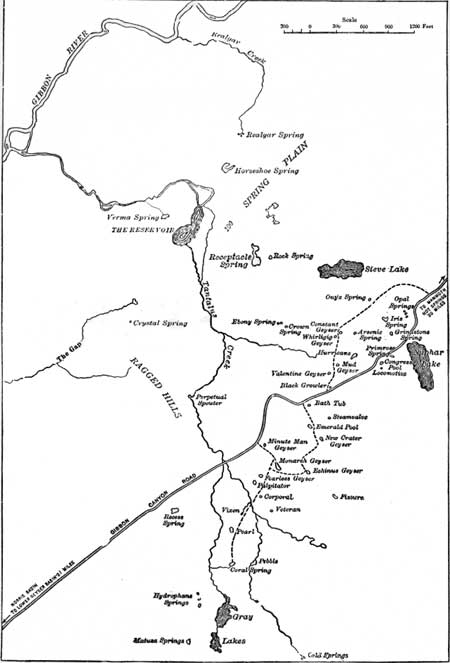

SKETCH MAP OF NORRIS GEYSER BASIN. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

|

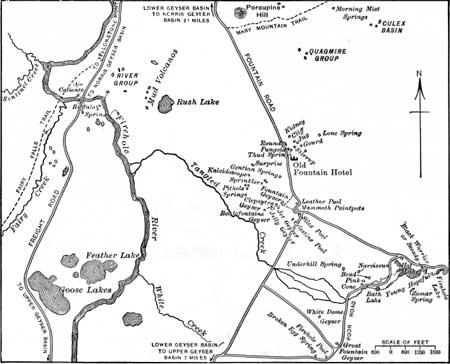

SKETCH MAP OF LOWER GEYSER BASIN. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

|

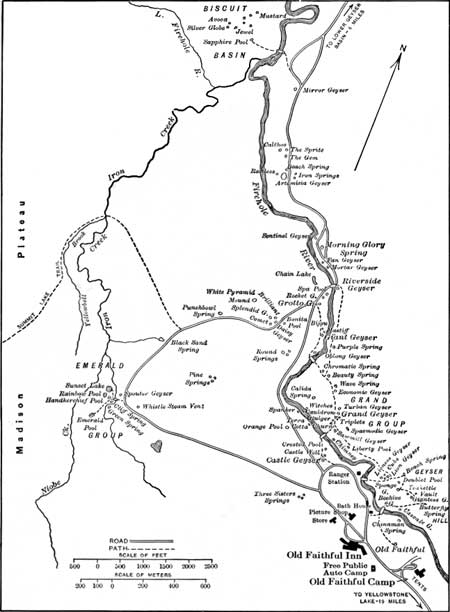

SKETCH MAP OF UPPER GEYSER BASIN. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The various geyser basins, or "fire holes," as they were called by the first explorers, each possess individual peculiarities which give character and interest to each locality. The most noted of these basins is, however, that known as the Upper Geyser Basin of the Firehole River, one of the headwaters of the great Missouri. The Upper Basin, as it is generally called, lies a little westward of the center of the park. It is a valley 1-1/2 miles long by one-half mile broad, inclosed by the rocky cliffs or darkly wooded slopes of the great Madison Plateau and drained by the Firehole River, along whose banks the largest geysers are situated. The whole floor of the valley is fairly riddled with springs of boiling water, whose exquisite beauty is indescribable. Light clouds of fleecy vapor curl gently upward from waters of the purest azure or the clearest of emerald, and, encircling rims of white marblelike silica, form fit setting for such great gems. A large part of the valley floor is covered with the white deposit of silica known as siliceous sinter, deposited by the overflowing hot waters.1 The weird whiteness of these areas, the gaunt white trunks of pine trees killed by the hot waters, the myriad pools of steaming crystal, and the white clouds floating off from the chimney-like geyser cones, form a scene never to be forgotten by those fortunate enough to behold it. Within this basin there are nearly 30 geysers, presenting many variations of bowl or basin, mound and cone, and whose eruptions are equally diversified in form and beauty.

1See "Formation of Hot Springs deposits," W. H. Weed, Ninth Ann. Rept. Director of U. S. Geological Survey, 1889.

|

| SPONGE GEYSER, UPPER BASIN. Photograph by F. J. Haynes. |

Sentinel, Fan, Riverside, Mortar, and Grotto greet one on entering the basin either by quiet steaming or by flashing jets. Giant, Splendid, Castle, Grand, Giantess, Lion, and Old Faithful are but a few of the wondrous fountains of the place. The last is most deserving of its name. Ever since its discovery, in 1870, it has not failed to send up a graceful shower of jets at average intervals of 60 to 75 minutes. Its beauty is ever varying, as wind and sunlight play upon it, and the mound about its vent is adorned with delicately tinted basins of salmon, pink and yellow, filled with limpid water whose softness is enticing. It is the geyser of the park, and indeed of the world, and many a visitor to "geyserland" departs without seeing any other of the many spouters in action and yet feels more than repaid for the journey. For beauty of surroundings the Castle will perhaps be awarded the palm; its sinter chimney or cone is formed of exquisite cauliflower or coral-like geyserite, whose general form makes the geyser's name appropriate. Its eruptions are now irregular. A stream of hot water is thrown up to a height between 50 and 75 feet for about 30 minutes, followed by the emission of steam, with a loud roar that can be heard for miles.

|

| ECONOMIC GEYSER,1 UPPER BASIN. Photograph by F. J. Haynes. 1No longer active. |

The greatest geyser of the park, and indeed the grandest of the whole world, was Excelsior, some 25 miles beyond the Norris Basin. Unlike the less capricious and more fountain-like geysers of the Upper Firehole, this monster of geysers did not spout from a fissure in the rock, nor from a crater or cone of its own building. It was a monster of destruction, having torn out its great crater in the old sinter-covered slope, builded by the placid and beauteous Prismatic Lake. The walls, formed by the jagged ends of the white sinter layers, were lashed by the angry waters that were ever undermining the sides and enlarging the caldron. The eruptions were so stupendous that all other geysers are dwarfed by comparison. The grand outburst was preceded by several abortive attempts, when great domes of water rose in the center and burst into splashing masses 10 to 15 feet high, while the waters surged under the overhanging walls and overflowed the slope between the crater and the river. Finally, with a grand boom or report that shook the ground, an immense fan-shaped mass of water was thrown up to a height of 200 or more feet, great clouds of steam rolled off from the boiling water, while large blocks of the white sinter were flung far above the water and fell about the neighboring slopes. Unfortunately, this monarch of all geysers has ceased to erupt.

|

| EXCELSIOR GEYSER.1 Photograph by F. J. Haynes. 1Ceased playing in 1888. |

Everywhere, save at the Norris Basin of the Yellowstone Park, geyser vents are surrounded by cones, mounds, or platforms of white siliceous sinter which, though built up into very beautiful forms, hides the true relation of the geyser vent to the fissures in the rocks, so that it has been generally believed, as stated by Tyndall,1 that the hot springs built up tubes of siliceous rock, that made them geysers. That this is not true is shown by several great fountains at the Norris Basin, that spout directly from fissures in the solid rock, notably the Monarch, Tippecanoe, and Alcove geysers.

1Heat as a mode of motion.

Prominent geysers and springs, based upon observations during season 1920.

| Name. | Height of eruption. |

Duration of eruption. | Interval between eruptions. | Remarks. |

| NORRIS BASIN. | ||||

| Feet. | ||||

| Black Growler | Steam vent only. | |||

| Constant | 15-35 | 5 to 15 seconds | 20 to 55 seconds | Quiescent in 1920. |

| Congress pool | Large boiling spring. | |||

| Echinus | 30 | 3 minutes | 45 to 50 minutes | |

| Emerald Pool | Beautiful hot spring. | |||

| Hurricane | 6-8 | Continuous. | ||

| Minute Man | 8-15 | 15 to 30 seconds | 1 to 3 minutes. | Sometimes quiet for long periods. |

| Monarch | 100-125 | Irregular | ||

| New Crater | 6-25 | 2 to 5 minutes | ||

| Valentine | 60 | Irregular | ||

| Whirligig | 10-15 | do | Near Constant Geyser. | |

LOWER BASIN. | ||||

| Black Warrior | Continuous | Small, but interesting geysers. | ||

| White Dome | 10 | 1 minute | 40 to 60 minutes | |

| Clepsytra | 10-40 | Few seconds | 3 minutes | |

| Fountain Geyser | 75 | 10 minutes | 2 hours | |

| Firehole Lake | Peculiar phenomena. | |||

| Great Fountain | 75-150 | 45 to 60 minutes | 8 to 12 hours | Spouts 4 or 5 times. |

| Mammoth Paint Pot | Basin of boiling clay. | |||

| Excelsior | 200-300 | About 1/2 hour | Ceased playing in 1890. | |

| Prismatic Lake | Size about 250 by 400 feet; remarkable coloring. | |||

| Turquoise Spring | About 100 feet in diameter. | |||

UPPER BASIN. | ||||

| Artemisia | 50 | 10 to 15 minutes | 24 to 30 hours | Varies. |

| Atomizer | 2 | |||

| Beehive | 200 | 6 to 8 minutes | 3 to 5 times at 12-hour intervals following Giantess. | |

| Cascade | Quiet again. | |||

| Castle | 50-75 | 30 minutes | Irregular | |

| Cub, large | 60 | 8 minutes | With Lioness | Short chimneys to Lion and Lioness. |

| Cub, small | 10-30 | 17 minutes | 1 to 2 hours | |

| Daisy | 70 | 3 minutes | 80 to 90 minutes | |

| Economic | 20 | Few seconds | Seldom in eruption. | |

| Fan | 15-25 | 10 minutes | Irregular. | |

| Giant | 200-250 | 60 minutes | 6 to 14 days | |

| Giantess | 150-200 | 12 to 36 hours | Irregular, 5 to 10 days. | |

| Grand | 200 | 15 to 30 minutes | 10 to 12 hours | |

| Grotto | 20-30 | Varies | 2 to 5 hours | |

| Jewel | 5-20 | About 1 minute | 5 minutes | |

| Lion | 50-60 | About 2 to 4 minutes | Irregular. | Usually 2 to 17 times a day. |

| Lioness | 80-100 | About 10 minutes | do | Played once in 1910, once in 1912, once early in 1914, and once in 1920. |

| Mortar | 30 | 4 to 6 minutes | do | |

| Oblong | 20-40 | 7 minutes | 8 to 15 hours | |

| Old Faithful | 120-170 | 4 minutes | 60 to 80 minutes | Usual interval 70 minutes. |

| Riverside | 80-100 | 5 minutes | 6 to 7 hours | Very regular. |

| Sawmill | 20-35 | 1 to 3 hours | Irregular | Usually 5 to 8 times a day. |

| Spasmodic | 4 | 20 to 60 minutes | do | Usually 1 to 4 times a day. |

| Splendid | 200 | 10 minutes | Not played since 1892. | |

| Sponge | 1 minute | 3 minutes | A small but perfect geyser. | |

| Turban | 20-40 | 10 minutes to 3 hours | Irregular. | |

Notable springs.—Black Sand Springs (about 55 by 60 feet), Chinaman, Emerald Pool, Morning Glory, Punch Bowl, Sponge, Sunset Lake.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

weed/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 02-Apr-2007