|

Animal Life in the Yosemite

|

|

|

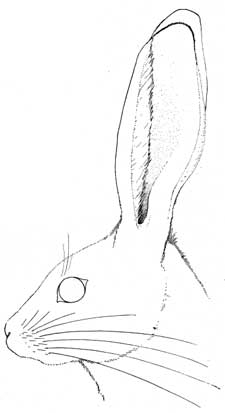

THE MAMMALS BLACK-TAILED JACK RABBITS. Lepus californicus Gray16 Field characters.—Of rabbit form but racy in build; ears longer than head (fig. 33); legs and feet relatively long and slender. Head and body 18 to 19 inches (460-480 mm.), tail 2-1/3 to 3-1/2 inches (60-90 mm.), hind foot 4-1/2 to 5-1/2 inches (118-140 mm.), ear from crown 5-3/4 to 6-1/2 inches (147-165 mm.); weight about 5 pounds (2.3-2.4 kilograms). General coloration above pale yellowish brown, ticked with black; under surface of body varying from pale buff to white; tail black above. Workings: 'Forms' (resting places) on ground beneath bushes; also paths leading in direct course across open country. Droppings: Flattened spheres, yellowish brown in color, about 3/8 inch in diameter, scattered on ground. Occurrence.—Common resident in Lower and Upper Sonoran zones on west slope of Sierra Nevada where recorded from Snelling and Lagrange eastward to Bower Cave and to slopes of Bullion Mountain (subspecies californicus). Also present in small numbers east of mountains in neighborhood of Mono Lake, as at Mono Lake Post Office (subspecies deserticola). See footnote for details. Inhabit chiefly open plains country, though some individuals live about clear areas in the chaparral or in open woods. Diurnal.

The California Jack Rabbit is a common species on the plains and rolling lands at the eastern margin of the San Joaquin Valley where our Yosemite section begins, and it also occurs to a limited extent in open areas in the foothills among digger pines and chaparral. In a few places jack rabbits enter the lower margin of the yellow pine belt, but they go no farther upward. The main forest belt of the central Sierras, the Transition and Canadian zones of the west slope, is devoid of rabbits of any sort. On the east side of the mountains there is a closely allied form, the Desert Jack Rabbit, which occurs in small numbers about Mono Lake. Our jack rabbit is strictly speaking a hare, more closely related to the White-tailed Jack Rabbit than to the cottontail and brush rabbits. The present species lives entirely out on the surface of the ground without taking to underground shelters. Its young at birth are fully haired and almost ready for independent existence. The adults when alarmed instead of hiding in shrubbery or bolting down into holes make off in the open and trust to their legs for safety. These are all characters of hares as contrasted with true rabbits. The present species is a black-tailed jack rabbit. The upper side of the tail, which is the surface presented to view when a hare is running, is extensively black and hence different in appearance from that of all the other rabbits of the region. The jack rabbit is of slender build throughout. The legs and feet are proportionately longer than in the cottontail and brush rabbit. When foraging quietly, the jack rabbit moves by short hops, keeping the soles of the hind feet on the ground and the long ears erect (fig. 33). But when thoroughly frightened, as when closely pursued by a hound, a coyote, or an eagle, the animal stretches out to the utmost extent, the ears are laid down on the back, only the toes touch the ground, and the body is carried low. In this position the rabbit covers two to three yards at each bound. The jack rabbit's whole being is modified for this sort of travel, for escape by speed in the open. Only once did we find a jack rabbit taking shelter in a hole, and that was a wounded animal. One shot near Lagrange lay quietly on the ground until the collector made a move to pick it up. Then the 'Jack' scrambled into a hole under some rim rock, whence it could not be dislodged. A typical meeting with a jack rabbit, near Coulterville, is described in our notes of May 11, 1919.

While we were camped along the shore of the Tuolumne River below Lagrange in May of 1919, jack rabbits were often seen close to the margin of the stream. Tracks and droppings indicated that they frequented the place. Whether they came down (off the adjacent mesa) to drink we were unable to ascertain. Their repeated occurrence close to the river, where there was no particular sort of forage to attract them, made this at least a possible explanation. Yet jack rabbits do live in many places where there is no water at all to drink.

The jack rabbit forages for a variety of materials, including not only grasses but also parts of brushy plants. Where man has taken possession of the country and planted alfalfa, grains, or other crops these animals naturally turn to the new materials and often take extensive toll. The erection of rabbit-proof fences and the killing off of the animals by various means have been resorted to in efforts to protect crops. In earlier years rabbit drives, participated in by all the residents of a region, were held in attempts to reduce the numbers of jack rabbits. Seasonal fluctuations occur in the jack rabbit population. In 1915 the numbers of the animals in the western part of the Yosemite section were moderate, not great enough to excite comment on the part of our field party. But in 1919 their numbers were notably greater. On the hills about Lagrange an animal would be started up every hundred yards or so. The rabbits were then common even through the chaparral as far into the hills as Coulterville. In the vicinity of the latter place individuals were come upon wherever there was any grass in the small clearings. Rabbits, like meadow mice, sometimes increase until they overrun the country, then suddenly decrease to a minimum. In earlier years this was true of the jack rabbits in the lower San Joaquin Valley, but since the great rabbit drives of the nineties, when thousands were killed by the ranchers, this great variation in numbers seems not to occur. The young of the jack rabbit when born are far advanced in their development as compared with the young of true rabbits. The body is fully covered with hair and the eyes are open. The body length at birth is about 6 inches and the animal weighs about 2 ounces. Growth is rapid and the young soon take on the rangy form of the adult. Even in the very young the ears are large (about 2 inches long at birth) and exceed the head in length so that no difficulty is experienced in identifying them as young jack rabbits. In the cottontail the ears are very short at birth, shorter than the head. The breeding season of the jack rabbit extends through most of the year, though a somewhat larger percentage of young is produced in the spring than in other seasons. A female (deserticola) taken at Mono Mills on June 19, 1916, contained 5 embryos. The average number in a litter, taking the country at large, is between 4 and 5. |

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

Animal Life in the Yosemite ©1924, University of California Press Museum of Vertebrate Zoology grinnell/mammals71.htm — 19-Jan-2006 | ||