|

YUKON-CHARLEY RIVERS

The World Turned Upside Down: A History of Mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, Alaska |

|

| PART I — BEFORE THE DREDGES |

CHAPTER ONE:

EARLY MINING ON THE UPPER YUKON

Early Mining in the Circle District

In Alaskan and the Canadian Yukon, the best known period of mining history was the great Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-98. By the time the thousands of prospectors landed at Dawson City in the Yukon Territory, most found the valuable ground already staked. Consequently, many of them either returned to their homes empty-handed or fanned out into the surrounding areas hoping to find new areas where they could make their fortunes. Many continued down the Yukon River to the already established Fortymile mining district and some went farther down river to the Eagle district. Approximately 150 miles farther down the river from the Eagle District lay the town of Circle, the jumpin-off point to the Circle district.

The first discoveries along the upper Yukon were made in the mid-1880s and production began in tributaries along the Fortymile River. Following these, in 1893, two Creoles named Pitka and Sorresca made additional discoveries in what later became the Circle Mining District. Their initial discoveries were somewhere on Birch Creek. News of the discovery started an influx of prospectors into the area and in the following spring (1894) discovery of the placers on Mastodon Creek. As prospectors continued to probe the drainages surrounding Birch and Mastodon creeks, gold was also discovered on Independence, Miller, Deadwood, and Boulder creeks, all within the Circle mining district. [1] In 1895, gold was found on Eagle Creek with discoveries made on Harrison and Porcupine Creeks later that winter. By 1896, active mining was taking place on all the principal streams in the Circle District. Although many other streams in the District would be mined as commercial placers, the Birch Creek and Mastodon Creek discoveries occurred well before those of the Canadian Yukon that sparked the Klondike Rush. [2]

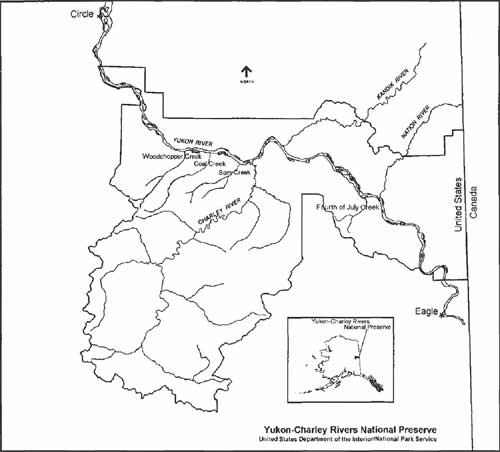

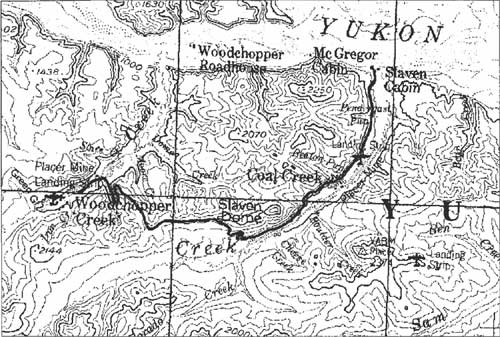

Gold mining continued to develop throughout the region between Circle and Dawson. Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek lie within the Circle mining district, approximately 110 miles downstream from Eagle and 50 miles up from Circle (Figure 1). Thsese creeks constituted one of three main gold mining areas within the Circle District. The other two were Mastodon Creek and Deadwood Creek. The placers found on these creeks saw the entire gamut of mining techniques used. Miners typically began with early pan and sluice work, followed by hydraulic and open-cut techniques and eventually dredge operations. The Coal Creek-Woodchopper Creek area includes Ben Creek and Sam Creek as well as their tributaries. However, only Coal and Woodchopper Creeks evolved to having dredges operating on them.

|

| Figure 1: Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, Alaska Early Mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Because of their association with dredging, many people assume that Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek's mining history started with gold. That however is not the case, at least on Coal Creek. The first record of mining activities comes on July 13, 1901. Mark E. Bray filed a bill of sale for 160 acres of coal mining ground he described as "situated on a small creek 8 miles from the Yukon." [3] As a result the creek earned the name "Coal Creek."

|

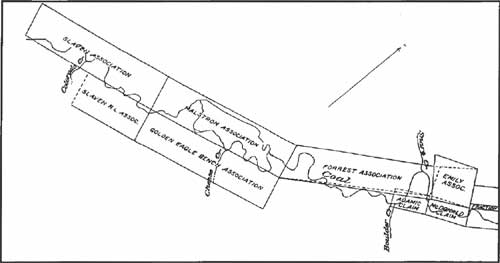

| Figure 2: Upper Coal Creek Claims. (click on image for a PDF version) |

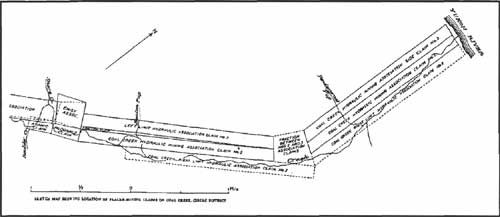

D.T. Noonan [4] filed the first placer mining claim on Coal Creek for the "Gertrude Bench" claim on November 11, 1901. [5] After Noonan's claim, over the next six years, individuals who eventually became well associated with mining activities on both Coal and Woodchopper Creeks staked additional claims. These include men like Frank Slaven, who, with assistance from Sandy Johnson (who had claims on Sam Creek), built the roadhouse at the mouth of Coal Creek. They also included W.P. Beaton and James Pendergast, both for whom tributaries to Coal Creek are named. A man by the name of Nels Nelson joined Slaven and the others with claims stretching from the mouth of Coal Creek approximately 10 miles upstream. Slaven's claims, along with those of Harold Malstrom and Frank Forrest in which Slaven shared interests in, occupied the upper 16,000 feet of the valley from Boulder Creek upstream beyond Colorado Creek. The Beaton and Nelson claims took in the lower 25,000 feet of the creek from the Yukon River to the mouth of Boulder Creek. [6]

|

| Figure 3: Lower Coal Creek Claims. (click on image for a PDF version) |

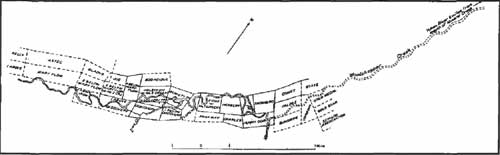

Of the two creeks, prospectors found gold on Woodchopper Creek first. Ira B. Joralemon wrote his initial report on the conditions in Woodchopper Creek in 1935. In it, he notes the placers on Woodchopper Creek and its tributaries, Mineral Creek and Iron Gulch, were worked "in a small way" for the preceding 40 years. In the 1920s, George McGregor staked some of the richest claims on the creek. In 1926, he and his partner, Frank Rossbach, staked the Discovery Claim at Mineral Creek. Between 1926 and 1935, McGregor staked five claims on Woodchopper Creek. [7] McGregor and the other claimants on Woodchopper Creek sold their claims to Alluvial Golds Inc. in 1935 marking the shift from small, individual miners to large corporate mining companies.

Surveys and reports from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) show that Woodchopper Creek and its tributaries were being worked more heavily than Coal Creek through the first third of the twentieth century. Although their names are not as well known to the region as those in Coal Creek, John Boyle, Frank Bennett, A. McDonald, S.O. Lee and C.I. Moon held the claims in Woodchopper Creek in the 1930s and eventually sold their interests to Alluvial Golds. In addition, George McGregor is the only personality still associated with the drainage. McGregor started as a prospector/miner then turned to trapping and fishing after selling his claims to Alluvial Golds Inc. One interesting highlight to the Woodchopper Creek claims is that a woman, Mrs. Bessie Olsen was the owner of record on several interests on claims as well as two claims outright. [8]

|

| Figure 4: Woodchopper Creek Claims. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Transportation and Communication

Placer mining in Alaska has undergone many changes throughout its history. Many of these focus on technological advances, from shovel and pans, to dredges, [9] to modern prospecting and recovery techniques involving computers. Mining on the Upper Yukon was no different from any place else in the territory.

One of the greatest hindrances to any mining activity in Alaska has been the difficulty associated with the lack of a transportation infrastructure. In 1903, Alfred Hulse Brooks; a geologist with the United States Geological Survey commented that:

The general backwardness of the Yukon field compared with that of Nome is, of course, in a large measure due to the differences in [gold] values, but must also be assigned to the isolation of the region. So long as developments are dependent on the present inadequate transportation facilities, the region will be handicapped. With the uncertainties of the river-steamboat service, the entire absence of roads, and the scarcity of trails, the placer miners of the Yukon district have had to face conditions which would have utterly disheartened less resolute men. [10]

This lack of reasonable transportation limited the amount of development work accomplished on many placer claims in the upper Yukon River region.

The original supply routes into the country came from Seattle and points south, through Skagway, and down the Yukon River to Eagle and thence farther downstream to the various creeks. To access Ben Creek, the original supply trail to the mining operations followed Sam Creek from its mouth at the Yukon. Winter mail carriers, such as the Biedermans, used this route, crossing over to Coal Creek when encountering bad ice conditions on the Yukon. Ernest Patty built a spur road to Ben Creek from the Gold Placers Inc. road on Coal Creek enabling heavy equipment to reach Ben Creek from Coal Creek. Constructing the landing strip at Ben Creek, facilitated by this spur road, further enhancing mining operations there. [11]

To service Coal Creek, steamboats and barges on the Yukon initially transported all materials and supplies. James Ducker's study of transportation in the Upper Yukon River area states that in 1922; the Alaska Road Commission (ARC) assumed responsibility for an eight-mile stretch of trail up Woodchopper Creek. [12] This trail in-turn branched over to Coal Creek (by way of Mineral Creek) and down the Coal Creek Road where it branched further to Boulder Creek, Ben Creek and Sam Creek (Figure 5). In the early years, the ARC primarily confined its work to building bridges along the trail. Later, in 1932, following a period of severe flooding, the ARC took an active role in rebuilding parts of the old dog sled trail. They went so far as to float logs from the headwaters of Woodchopper Creek to repair bridges that had washed out. The ARC constructed the road from Slaven's Landing, up the Coal Creek valley to Camp No. 1 which was located near the mouth of Cheese Creek. After they began work on Camp No. 1, in the summer of 1935, Gold Placers Inc. extended the road over to Woodchopper Creek to support the dredging operations there. This road follows the Coal Creek valley upstream until it makes several switchbacks to climb a steep portion and then follows the ridge for about a mile and a half before dropping down Mineral Creek and on to Woodchopper Creek. [13] In addition, a telephone line ran along the road's right-of-way providing communication between the two camps. According to Dale Patty, who managed the mining operations from 1954 to 1960, he "sometimes felt like opening a window and yelling" because of the poor quality of communication offered by the crank-style, battery operated telephone. [14]

|

| Figure 5: Coal Creek to woodchopper Creek Road (USGS 1:63,360). (click on image for a PDF version) |

By the late 1930s, operations at Mastodon and Deadwood Creeks were linked by road, and in the cases of some smaller operations, trails, to the Steese Highway, which ran between Fairbanks and Circle. Operations in and around Coal Creek were still dependent on getting their equipment and supplies by way of boats on the Yukon River and to a limited degree, by air support. This situation has not changed, even at the dawning of the 21st century.

Early Development Work on the Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek Placers

During 1905, L.M. Prindle, of the USGS, reported that Coal Creek, Woodchopper Creek, Washington Creek and Fourth of July Creek produced at least $15,000. According to several unsubstantiated reports, the figure had a potential to rise as high as $30,000. [15] Alfred H. Brooks, also of the USGS, reported the same year that the majority of this production came from Woodchopper Creek. [16]

Several years later, the drainages between Woodchopper Creek and Fourth of July Creek held enough promise for mineral development that L.M. Prindle and J.B. Mertie, Jr. of the USGS prepared a special report on the region for the Mineral Resources of Alaska: Report on Investigations in 1911. The authors provide a detailed description of the region, concentrating on each creek. In it, they also discuss the geological history of the area and provide educated predictions on the source for the mineralization. In their description of Coal Creek, they erroneously state that gold was discovered here first in 1910. In their description of recovered gold, they note that "pieces worth $12 to $14" had been found — and this was all during the work before actually beginning mining operations. [17]

Prindle and Mertie found the paystreak in Woodchopper Creek to be even better than that in Coal Creek. They estimated it actually consisted of two parallel channels twelve to fourteen feet wide, with a possibility of a third channel eighty feet wide. After removing the over-burden, which varied up to 30 feet thick, the paystreak averaged 1-1/2 to 4 feet thick. Here, the gold was "course," with the largest nugget found having a value of $30. Miners on Woodchopper reported their gold had values ranging from $19.09 to $19.30 per ounce. [18] According to Prindle and Mertie, "these were the highest values found in the Yukon Province." [19]

By 1912, the USGS reported that "from seven to fourteen men were engaged in mining on Woodchopper Creek," primarily on its tributaries: Mineral Creek, Iron Creek and Alice Gulch. Coal Creek and its tributaries Boulder and Rose Creeks had between ten and twenty men "either prospecting or mining." That year, there were also a few men, mainly prospectors, working on "Sams Creek" and some on Fourth of July. However, the report does not provide production figures. [20]

The following year, there were ten men working on Fourth of July Creek. Others were preparing to begin work "whenever the water supply was adequate." Reports from early in the season showed that Woodchopper Creek held promise as a "better producer than ever before" with twenty men working the creek and its tributaries year round. Coal Creek operations continued to be small scale with "six or eight" men mining on it. [21]

The values associated with the placer at Coal Creek varied considerably from claim to claim. Ira Joralemon, an internationally known geologist who examined the Coal Creek claims in the early 1930s, reports that Nelson and Beaton, after working approximately 50,000 square feet of bedrock, averaged approximately 75 cents per square foot. This is after removing the overburden to get to down to the paystreak lying at or near bedrock.

|

| Early mining camp on Coal Creek. This is likely Frank Slaven's claims and operation. Note the gin pole on the left for hauling paydirt out of the ground and the two cabins on the right. Frank Slaven Collection, courtesy of Sherrie Harrison. |

Reports state that Slaven's claims, on the other hand, averaged $1.14 per square foot in 1914. All of these claims were said to be "unusually rich." 22]

Several years later, Brooks reported that there were "about 10 mines operating and 25 men employed during the summer of 1914" in what he called the "Woodchopper Creek region." These included ten camps operating in the winter, primarily on Coal Creek. That year, preparations were made to install a hydraulic operation at the mouth of Mineral Creek in the Woodchopper Creek drainage. In 1914, the entire Circle district produced $215,000 worth of gold, an increase over an estimated $175,000 produced the previous year. [23]

The first dredge to work in the district worked on Mastodon Creek, southwest of Circle. It came from Dawson in 1911. The operators found it entirely unfit for further service and dismantled it in 1914. Miners brought a second dredge to work on nearby Mammoth creek that year with expectations that it would be in service during the entire 1915 season. The dredge specifications as reported by the USGS closely resembled those for the dredge eventually put into service on Coal Creek. It had 3-1/2-foot buckets [24] and a close-connected line. Powering the dredge were one hundred seventy-horsepower steam engines, with an estimated daily capacity of 2000 cubic yards and capable of digging ground twelve to sixteen feet deep. [25]

|

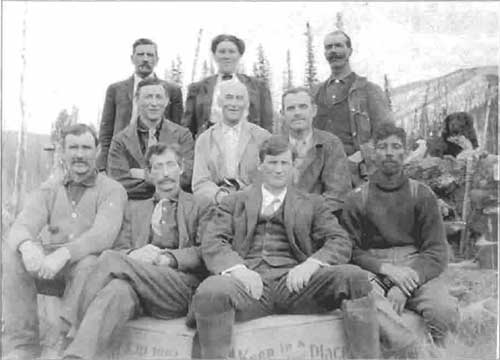

| "Those Came Early and Stayed Late, the Miners of Coal Creek." This photo was taken by Walter Harvey in August 1927 while he and his father Samuel Downs Harvey retraced Sam's trek from Indiana to Coal Creek. Back: Nels Nelson, Hattie (Mrs. Robert) Darlington, George Davis. Middle: Robert Darlington, Samuel Downs Harvey, Jack Boyle. Front: Charles Boyle, William P. Beaton [26], Frank Slaven, Charles Armstrong. Frank Slaven Collection, courtesy of Sherrie Harrison. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

yuch/beckstead/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 10-Feb-20012