|

YUKON-CHARLEY RIVERS

The World Turned Upside Down: A History of Mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, Alaska |

|

CHAPTER TWO:

WHO WORKED THE CREEKS?

INTRODUCTION

For the most part, recent historical research on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek has been confined to the period after Gold Placers, Inc. and Alluvial Golds, Inc. put dredges on the creeks in 1936 and 1937 respectively. This only covers the last half of the active period of mining here. Previously little information was available regarding the preceding four decades when men and women were prospecting, mucking, poking, drifting and sluicing these creeks and their tributaries. This chapter examines those individuals. Since the records are few and far between, a quantitative examination provides an overview followed by biographies, albeit short ones, on some of the more prominent individuals who lived and worked claims on the creeks.

Examining the various record books maintained by the Circle Mining District recorder resulted in a list of 320 individuals whose names appear connected to claims on Coal Creek, Woodchopper Creek and their various tributaries. Based on this, and other archival information including letters and diaries, along with interviews with miners and their descendants, four groups of individuals emerge. The first group, those who "came early and stayed late" consists of people staking claims early on, generally before 1907. They remained on their claims through the mid-1930s when they sold them to the two dredging companies. Among these are Frank Slaven, John Boyle, Sivert O. Lee, Frank Bennett, John Holmstrum [1] and Bessie Currie [2].

The second constitutes individuals who invested in others to prospect and work their claims. Among these are men such as those from the Dawson Daily News who grubstaked Frank Slaven and James Pendergast on Coal Creek. Their financial backers include: William McIntyre, William B. Reinhardt, Charles B. Settlemeier, Albert Forrest, Harold Malstrom, Richard Roediger and Arthur H. Dever. This group also held several "associated" claims under the name of the "Coal Creek Dredging and Mining Company." [3] Although the Dawson Daily News group would also qualify for membership within the first category of individuals, they are not included because their interests were purely of a financial nature.

There is a chain of claimants, John Holmstrum, Frank Rossbach and George McGregor that extends this first 'group' even farther. Holmstrum was one of the first to stake claims in 1901. He partnered with Rossbach from 1913 to 1923 when he left the country. McGregor then joined with Rossbach working their claims until 1926 when Rossbach returned to Germany. McGregor remained on Woodchopper and the Yukon until the early 1960s when he moved to Eagle. He is also the author of an extensive collection of journals covering most of the period. As a result, McGregor offers the researcher an opportunity to see the workings of Woodchopper and Coal Creek through his eyes.

The last two groups of individuals identified on the creeks include those who came during one of the several rushes to the area, staked claims and never followed through with proving them up or for any number of reasons abandoned them and moved on. The last group includes those who lived outside Alaska and granted power-of-attorney to any of a variety of prospectors and miners who would then stake claims in their names. Although these are similar in nature to those in the second group, these individuals appear to have never come to Alaska, much less worked the creeks. The primarily constitute family and friends of miners working the creeks who likely offered to get their acquaintences in on a "good thing."

It appears that coal claims were the first staked in the drainages. Steamboats were plying the Yukon River bringing passengers and freight from St. Michael on the Bering Sea coast to Dawson. Their primary fuel supply was wood cut during the winter by individuals working as woodchoppers. Steamboats made periodic stops along the river to take on huge quantities of cordwood. Boats traveling upriver would burn upwards of a cord of wood each hour. [4] The transportation companies saw coal as a potential alternative to wood, provided it could be located in sufficient deposits, mined and transported to the riverbank. [5]

On July 13, 1901, Mark E. Bray sold his interests in a coal claim on Snare Creek, located approximately six miles up Coal Creek from the Yukon River, to William Moran. [6] D.T. Noonan and David Petrie witnessed the document. Subsequently this claim changes hands several more times including when it W.W. Chandler, William H. Carpenter, Mary L. Lewis and John Lauchurt relocated it in 1910. [7] It is unclear if any appreciable amount of coal was ever mined from Snare Creek.

Daniel T. Noonan, [8] of Delamar, Nevada, filed the first gold claim on Coal Creek in mid-November 1901. [9] Noonan located his 20-acre claim on the right limit [10] of Coal Creek on August 23, 1901. The same day, Daniel M. Callahan also located a 20 acre mining claim he called "No. 1 Below Discovery on Magnet Hill," also on the right limit of Coal Creek presumably in the vicinity of Noonan's claim. [11] Unfortunately, Noonan is among those who staked claims and did not follow up with them. He disappears from the record after filing an associated claim for 160 acres on Coal Creek in 1902. [12] Among those listed as Callahan's co-claimants are: D.T. Noonan, R.R. Reed, John Linquist, Edward McGrath [13], Sherman Fraker [14], F. Overgaard, Julius Stankus and Dick Shine.

From 1900 through 1948, there were 565 claims filed on the two drainages. The number of claims filed over the years follows a pattern of peaks and valleys. After Noonan and Callahan staked their claims in 1901, ten others recorded claims that year along with 27 more the following year. In 1903 however no claims were recorded. In 1904, people staked nine claims followed the next year by the largest number of claims (95). Then a steady decline takes place until again it bottoms out with no claims staked in 1909. This trend of rising and falling numbers continues with peaks and valleys in the following years: 1910 (36 claims), 1912 (0 claims), 1916 (22 claims), 1924 (0 claims), 1927 (11 claims), 1929-34 (0 claims), followed by a flurry of locations in 1935 (57 claims). This pattern becomes more evident and is explained by comparing the ebb and flow of locations with the various rushes occuring around Alaska as shown in the following tables:

Number of Claims Staked on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek With Corresponding Gold Rush Locations And Major Historical Events of the Twentieth Century

| Historic Event or Gold Rush Location [15] | Year | Claim Filed |

| Fortymile | 1886 | 0 |

| Circle | 1893 | 0 |

| Eagle, American Creek | 1895 | 0 |

| Gold found on Bonanza Creek in the Klondike | 1896 | 0 |

| 1897 | 0 | |

| Nome/Seward Peninsula | 1898 | 0 |

| 1899 | 0 | |

| Subtotal (1890-99) | 0 | |

| Historic Event or Gold Rush Location [16] | Year | Claim Filed |

| 1900 | 0 | |

| 1901 | 12 | |

| Fairbanks | 1902 | 27 |

| 1903 | 0 | |

| 1904 | 9 | |

| 1905 | 95 | |

| 1906 | 32 | |

| 1907 | 44 | |

| Iditarod | 1908 | 10 |

| 1909 | 0 | |

| Subtotal (1900-10) | 229 | |

| Historic Event or Gold Rush Location [17] | Year | Claim Filed |

| 1910 | 36 | |

| 1911 | 19 | |

| 1912 | 0 | |

| 1915 | 6 | |

| World War I begins | 1914 | 16 |

| 1915 | 16 | |

| 1916 | 22 | |

| 1917 | 6 | |

| World War lends | 1918 | 4 |

| 1919 | 6 | |

| Subtotal (1910-19) | 131 | |

| Historic Event or Gold Rush Location [18] | Year | Claim Filed |

| 1920 | 6 | |

| 1921 | 5 | |

| 1922 | 6 | |

| 1923 | 1 | |

| 1924 | 0 | |

| 1925 | 2 | |

| 1926 | 8 | |

| 1927 | 11 | |

| 1928 | 5 | |

| Stock market crashes, Great Depression begins | 1929 | 0 |

| Subtotal (1920-29) | 44 | |

| Historic Event or Gold Rush Location [19] | Year | Claim Filed |

| 1930 | 0 | |

| 1931 | 0 | |

| 1932 | 0 | |

| 1933 | 0 | |

| Gold goes to $35.00 an ounce (troy) | 1934 | 6 |

| McRae & Patty begin acquiring claims for Gold Placers Inc. [20] | 1935 | 57 |

| Coal Creek dredge begins operation | 1936 | 20 |

| Woodchopper dredge begins operation | 1937 | 2 |

| 1938 | 2 | |

| 1939 | 8 | |

| Subtotal (1930-39) | 95 | |

| Historic Event or Gold Rush Location [21] | Year | Claim Filed |

| 1940 | 13 | |

| World War II begins | 1941 | 4 |

| Order L-208 closes gold mines | 1942 | 0 |

| Coal Creek dredge idle | 1943 | 0 |

| Both dredges idle | 1944 | 32 [22] |

| Woodchopper dredge idle | 1945 | 4 |

| 1946 | 4 | |

| 1947 | 5 | |

| 1948 | 4 | |

| Coal Creek dredge idle | 1949 | 0 |

| Subtotal (1940-49) | 66 | |

| Total Claims Filed (1890-1949) | 565 | |

Each time prospectors made a new discovery elsewhere in Alaska, people who had been unsuccessfully working Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek without finding gold in the quantities they hoped, joined the rush to the new diggings in their constant search for the next El Dorado. Other contributing factors in the number of claims being staked included international events such as World War I and the stock market crash of 1929. Following the economic downturn of the Great Depression, raising the price of gold to $35.00 an ounce in 1934 brought new life to the once stagnant region.

| Years | Claims Filed | Percentage |

| 1900-1909 | 229 | 40.5 |

| 1910-1919 | 131 | 23.2 |

| 1920-1929 | 44 | 7.8 |

| 1930-1939 | 95 | 16.8 |

| 1940-1949 | 66 | 11.7 |

| 1900-1949 | 565 | 100.0 |

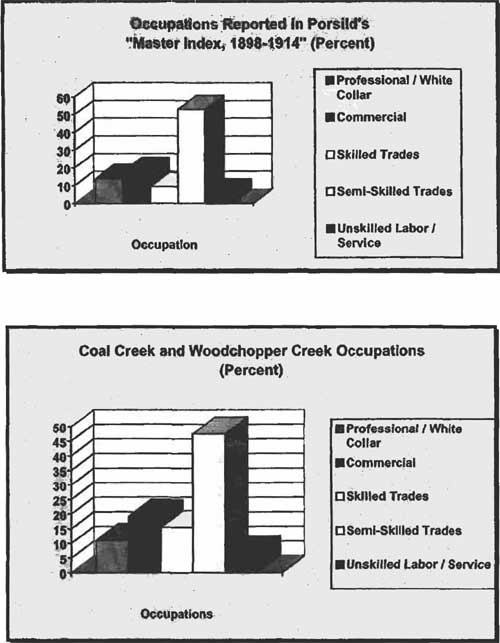

In examining the occupations of those claiming ground on the creeks, it is interesting to note the variety of jobs people reported. Using the classification system developed by Charlene Porsild in her book Gamblers and Dreamers: Women, Men, and Community in the Klondike reveals the following statistical breakdown. Eleven percent of those holding claims on the creeks were involved in professional or white-collar occupations, 19.2% were in commercial activities, 15.5% were skilled, while 47.5% were semi-skilled. The remaining 6.8% fall into the unskilled and service occupations. [23] Comparing Porsild's findings in the Klondike with those on the creeks reveals that Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek are simply microcosms of the demographics associated with the Klondike. The percentages made up of each occupational class for those on the creeks was similar to those reported in the Klondike over time as illustrated by the table below:

| Occupation | Klondike 1901 [24] |

Klondike 1885-1914 [25] |

Coal Creek/ Woodchopper [26] | |||

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | |

| Professional / White Collar | 615 | 9.0 | 1074 | 13.9 | 24 | 11.0 |

| Commercial | 582 | 8.5 | 1368 | 17.8 | 42 | 19.2 |

| Skilled Trades | 1031 | 15.1 | 722 | 9.4 | 34 | 15.5 |

| Semi-Skilled Trades | 2986 | 43.7 | 4093 | 53.1 | 104 | 47.5 |

| Unskilled Labor / Service | 1618 | 23.7 | 446 | 5.8 | 15 | 6.8 |

| Total Workforce | 6832 | 100.0 | 7703 | 100.0 | 219 | 100.0 |

Porsild's Master Index represents a more accurate depiction of the demographics of the Klondike due to the manner Canadian officials conducted the 1901 census. The 1901 Yukon census reveals a fairly high percentage of individuals (23.7%) in the unskilled labor category. These individuals for the most part constitute entertainers, gamblers, criminals, vagrants, manual laborers, and although most may disagree with Porsild's decision to include them here, wives. When looked at over time, this figure drops dramatically to 5.8% in the Klondike. The largest declines are shown in the number of cooks/waiters/bartenders (377 in 1901 down to 49 in the Master Index), domestic servants (108 in 1901 down to 12), manual laborers (247 down to 23) and wives (564 down to 169). This in part is attributed to the community's evolution from a booming mining town to a more stable community with more "traditional" values. Also, many of those individuals who found themselves without claims, without sufficient employment to provide a living, and without the means to support themselves in Dawson either turned tail and returned from whence they came, or joined the throng rushing off to another Eldorado.

One would assume that most if not all of the 565 people who filed claims on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek would consider themselves miners. In actuality mining accounts for less than half as is illustrated by the following tables (n=219). [27]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Turning from a quantitative examination of the people on the creeks, let us now examine who they were on a more personal basis.

THE LADIES OF THE CREEKS

Many people hold the misconception that mining is a man's enterprise. Although the vast majority of those who worked the creeks were male, a fairly substantial group of women held claims either as co-claimants with male partners, or in some cases in their own names. Of the 320 claimants identified through claim location records, 24 were women. Most of these were wives of men who also staked claims on the creeks. In some cases, they were acquaintances or relatives of men who staked claims. In one case, Bessie Currie, outlived her first husband, James H. Currie, later married Emil Olson and continued to own and operate her claims into the mid-1930s.

These women were not strictly wives or housekeepers. There were professional women on the creeks as well. Some managed hotels or restaurants, some operated roadhouses, one even worked at a laundry in Skagway. Two appear to have been practicing the world's oldest profession in Dawson at the time they staked their claims.

These brief biographies offer the opportunity to peer into the world of women who held claims on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek before the dredges came.

BRENTLINGER, FLORA E.

Flora E. Brentlinger, along with her husband Fred Brentlinger, provide interesting insights into the social history of the Yukon and the various Yukon-Alaskan gold rushes. Fred Brentlinger missed the rush to the Klondike gold fields. Instead, he came north as part of the Nome rush. In 1901, he appears in Polk's Gazetteer as a miner in Nome remaining there for two years. There is an eight-year hiatus until he again appears in claim records, in 1910, along with seven others staking a 160-acre placer claim on the main channel of Coal Creek. [33]

|

| An undated photograph of the Roadhouse shows Flora Brentlinger with two unidentified men (circa 1913-1926). The man on the left fits the physical characteristics of Frank Rossbach who had claims on Mineral and Alice Creeks. Frank Rossbach Collection, photos courtesy of Dietrich Rossbach. |

|

| Undated photograph of Flora Brentlinger (circa 1913-26). She and her husband Fred Brentlinger ran the Woodchopper Roadhouse until the early 1930s. |

On July 29, 1911, the Brentlingers purchased a lot in Circle, on the northwest corner of Front and "E" Streets, from William H. McPhee. [34] Within four years, the Brentlingers owned a number of lots in Circle, including the Tanana Hotel and Restaurant that they operated in 1911-12. [35] They continued to become increasingly involved in the business community in Circle with Fred Brentlinger serving as a notary public. [36]

Filing under the names of F.E. and Flora E. Brentlinger, she staked claims on Webber Creek (1915) [37] and Grouse Creek (1916) [38] a tributary of Woodchopper Creek. Her agent, John Cornell who also staked the adjacent claim in his own name, staked the Grouse Creek claim. [39] Her husband filed claims on Coal Creek beginning in December 1910 [40] and continued filing claims on Woodchopper and Caribou Creeks through 1928. [41]

|

| Woodchopper Roadhouse, circa 1913 - 1926. The woman in the photograph is likely Flora Brentlinger with her husband Fred on the right. It is uncertain who the other two men are. However, one may be Frank Rossbach who had claims at Mineral Creek. Frank Rossbach Collection, photo courtesy of Dietrich Rossbach. |

For nearly the next two decades, the Brentlingers are actively staking claims on both Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek. Eventually moving from Circle, they took over the Woodchopper Roadhouse, acquiring it from Valentine Smith who built it in the early 1900s. The Brentlingers passed it on to Jack and Kate Welsh following Fred's death in the early 1930s. [42] From Woodchopper, Flora Brentlinger went to Manley Hot Springs where she, along with C.M. "Tex" Browning, purchased the Manley Hot Springs farm from Frank Manley. They retained the farm until 1950 when Bob Byers, operator of Byers Airways bought it from them. [43]

CHAMBERS, MARGARET

Margaret Chambers resided in San Francisco, California in 1905 when she granted a power-of-attorney to Henry Melzer, of Ironton, Missouri, to stake mining claims on her behalf in Alaska. [44] Eventually, Ms. Chambers moved to Dawson City where she worked as a "servant." [45]

It is interesting to note that recently several scholars have identified several euphemisms used by census takers (and by similarity those compiling information for the R.L. Polk Company in producing the Polk's Gazetteers) for women working as prostitutes. Numerous connections have been made to women listing their official occupations as: dressmaker, housekeeper, and tobacconist, with those practicing the oldest profession. [46] In addition, some women were able to work out good terms and conditions for themselves in the employ of wealthy miners where they performed the duties of housekeeper or servant. [47] This being the case, it is highly probable that Ms. Chambers was in fact a member of Dawson's demimonde.

While in Dawson, she granted a second power-of-attorney to Mr. Otis Franklin Jenkins. [48] Her ties to Coal Creek are through two claims filed on her behalf in 1905. Through her power-of-attorney, Henry Melzer filed for a 20-acre claim called "No. 1 Above Discovery" on the left fork of Iron Creek, a tributary of Woodchopper Creek on January 5, 1905. [49] On the same day, Melzer filed for the Discovery Claim on the same creek. With the two adjacent claims, they essentially controlled twice the amount of placer ground (40 acres) as he could as an individual (20 acres).

Later that year, on August 9, 1905, again through her power-of-attorney, Thomas L. Newlands, filed a second claim for Ms. Chambers for the "Hillside No. 4 Above" on the left fork of Colorado Creek, a tributary to Coal Creek. [50] In a case similar to that with Melzer, Newlands filed for the Discovery Claim on Tenderfoot Creek, a tributary to the left fork of Colorado Creek. [51] This gave Newlands and Chambers claims above the mouth of Tenderfoot Creek and adjacent to the mouth of the creek.

DARLINGTON, MRS. HATTIE BELLE McEVOY

The Darlington's presence on Coal Creek and Woodchopper started in July 1905 when Robert H. Darlington filed for a one-half mile square homestead (160 acres) at the mouth of Woodchopper. This property is located on the right bank of the creek, bounded by Woodchopper Creek and the Yukon River. [52] Because of the vagary of the description in the location notice, it is difficult to identify exactly where the boundaries lie for this homestead. However, it is the only homestead filed at the mouth of the creek and as such may well be for the property on which the Woodchopper Roadhouse sits.

|

| Hattie and Darlington next to their cabin on Boulder Creek (n.d.). Samuel Downs Harvey collection, photo courtesy of Leona Beck. |

In November of the same year, Robert Darlington filed a claim on the left limit [53] of Rose Creek, a tributary of Coal Creek. [54] The following year, he filed an additional claim for No. 1 Above Discovery on Woodchopper Creek. [55]

Hattie Darlington was born Hattie Belle McEvoy on January 27, 1881 in Gray's Hollow, Nova Scotia. She married Robert Darlington at the age of 26 on October 27, 1907 while both of them lived in Nova Scotia. After their marriage, the family lost track of the couple. [56]

Hattie Darlington is one of eight co-claimants for the Darlington Association Claim on Coal Creek. The claim, filed on March 22, 1911, lists three Darlington family members as well as Valentine Smith, William Culligan, W.P. Beaton, Nels Nelson and Christ Gableman as co-claimants.

DIETZ, MINNIE

Minnie Dietz and her husband Christ. [57] Dietz are two of eight co-claimants in the Birch Bench Association claim on the left bench of Coal Creek. The association's agent, Jesse U. Powers who actively prospected and mined on Woodchopper Creek, filed the claim. In 1909, when Powers filed the power-of-attorney, Minnie and Christ were living in Tenino, Washington. [58] Also listed as co-claimants are: C.S. Vanderslice, E.M. Gallagher, Alex. Patterson, Ed Grignon, Eugene Powers, W.W. Powers and Christ Dietz. It is assumed that Minnie and Christ Dietz are husband and wife. [59] Although Ed Grignon and Jesse U. Powers were long time prospectors along the upper Yukon River, this is the only claim record in either of the Dietz' name. [60]

FINLAYSON, KATIE

Canadian records indicate that Ms. Finlayson came north on July 20, 1900 when the Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) recorded her crossing Chilkoot Pass and entering the Yukon Territory. She traveled down the Yukon River accompanying scows Nos. 488 and 489 arriving in Dawson City. [61] Two placer mining claims are recorded in the name of "K. Finlayson" in the Klondike, the first in 1900-01 [62] and the second in 1902. [63]

Frank Finlayson and his partner O.S. Clark staked the "No. 4 on Alice Creek" on July 28, 1905. [64] Five years later, Katie Finlayson enters the picture when her name appears with three other co-claimants (Frank L. Finlayson, Frank Jewett and C. Finlayson) on the "Anaconda" and "Boomerang" claims on Woodchopper. [65] On the same day, July 19, 1910, Frank Finlayson filed for an associated 100-acre claim with four others (J.M. Pompal, Louise Pompal, C. Finlayson and Frank Jewett). [66] It is interesting to note that for some unknown reason, Katie Finlayson's name is not among the co-claimants. After the claims were filed in 1910, Finlayson's name no longer appears in historical records leading one to assume that they left the country.

GREATHOUSE, JENNIE

Jenny Greathouse falls into the category of people who had claims filed in their name and did not come to Alaska to work them. She signed a power-of-attorney over to her step brother, Frank Slaven, to file claims on her behalf. She held part of an associated claim, called the Golden Eagle Bench Claim, on Coal Creek as a co-claimant with Slaven and six other individuals. [67] Two different documents proving this were filed with the Circle Mining District recorder in 1935. The first, filed by Frank Slaven on August 16, 1935, shows her living in Santa Cruz, California. The second, filed by attorney L.V. Ray, who worked with Ernest N. Patty for Gold Placers, Inc., was filed on September 3, 1935 and reports Douglas, Arizona as her residence. [68]

|

| Jack Slaven (left), Jenny Slaven Greathouse (center) and Emma Slaven (seated). Frank Slaven held powers-of-attorney for all three of his family members. Photo courtesy of Sherrie Harrison. |

LEWIS, MARY L.

In checking the records for the Circle Mining District, one finds that on August 6, 1910, four individuals: Wallace Chandler, Mary L. Lewis (by her attorney-in-fact Wallace W. Chandler), John Lauchurt and William H. Carpenter (by his attorney-in-fact John Lauchurt) filed for an associated 640 acres of coal lands. The associated claim was comprised of four individual claims of 160 acres each: the Black Diamond, the Ruby, the Enterprise and the Jumbo. [69] Mary Lewis and her partners represent those who came to the North seeking gold and fortune only to find that upon arriving in Dawson City the surrounding areas were already staked. Like many others, they were forced into wage paying jobs to survive and yet remained in the country for many years.

Of the four, Chandler arrived in the Yukon in mid-March 1900 when the Northwest Mounted Police at Chilkoot enumerated him. [70] By 1907, he was working as a clerk at the Floradora Hotel [71] in Dawson City, a position he continued to hold through 1910 when they staked their claims on Snare Creek. [72] William H. Carpenter also worked at the Floradora Hotel in Dawson City in 1910. [73] In Carpenter's case, he performed the duties of a porter.

Mary Lewis, on the other hand, enters the Dawson scene in 1905 when Polk's Alaska Yukon Gazetteer lists her as a resident but provides neither an address nor occupation. [74] Four years later, in 1909, her occupation is noted as selling "cigars", then in 1912, it shows she is selling "cigars and confections." [75]

In her autobiography, Martha Black describes three different groups of women living and working in the Klondike. They were, according to Black:

members of the oldest profession in the world, who ever follow armies and gold rushes; dance hall and variety girls, whose business was to entertain and be dancing partners; and a few others, wives with unbounded faith in and love for their mates, or the odd person like myself on a special mission. [76]

Historians Lael Morgan and Charlene Porsild recently published histories of prostitution in the North. [77] While Morgan's book, Good Time Girls, focuses mainly on biographies of a number of "sporting girls", Porsild's, Gamblers and Dreamers: Women, Men, and Community in the Klondike, undertakes a demographic community study of Dawson and the Yukon. Prostitutes were right on the heels of men seeking their fortunes in the gold fields. In the end, they were mining the miners for their gold.

Dawson provides an interesting study of prostitution and the evolution of community "values." Initially, prostitutes plied their trade from tents and other makeshift shelters. Eventually they became increasingly entrenched operating alongside or in conjunction with saloons and dancehalls. These in turn were intermixed between grocers, banks and assay offices along the main streets. Following a disastrous fire in 1899, Dawson authorities traced its origin to a prostitute's hotel room. They also seized upon the opportunity to move the red-light district further from the center of town. They required all "sporting girls" to relocate to Fourth and Fifth Avenues. As the community continued to grow and stabilize following the mass exodus of argonauts to the beaches at Nome, in 1901 the red light district moved again, this time to a swampy lowland across the Klondike River called "Lousetown." [78]

The NWMP and Dawson authorities found that, trying to force prostitution out of a community only moved it underground. Soon complaints were made of prostitutes and pimps moving back into the town. Instead of having brothels operating openly, they were resurfacing in the guise of cigar stores, candy stores and laundries. [79] As had previously been the case with "cleaning up" sex crimes, authorities made a minimal show of force. When others noticed the lack of prosecuting those moving back into the community, they soon joined the migration.

By 1907, what had previously been enforcement by benign neglect became much more vigorous with pressure coming from the federal government in Ottawa. The Floradora was one of the very few dancehalls still operating. With greatly reduced business, the hotel employed approximately 15 women, without a liquor license. [80]

In 1911, the superintendent of police reported to the commissioner of the Yukon that there were still some women in town who, "under the guise of dress-makers and keepers of cigar stores are said to be carrying on prostitution, but they are quiet, make no display on the streets, and except by reputation no one knows to what class they belong." [81]

Ms. Lewis represents the Dawson City demimonde, a part of a rather stratified order within the "entertainment" community. Unlike Ms. Black, she fell into the category of 'members of the oldest profession in the world.' She in effect was a prostitute who operated her "cigar and candy" store right in the heart of the city on First Avenue. [82]

MONGRAIN, LUCY

Like many of the claimants in the records for Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, Lucy Mongrain appears only once. Her attorney-in-fact, Charles E. Mongrain filed a 20-acre claim location for "Bench No. 2 Coal Creek", on May 1, 1907. [83] Over the two previous years, Mr. Mongrain had also located claims "No. 4 on the Left Fork of Colorado Creek" (1905) [84] and "Bench No. 1 Above Boulder Creek" (1906). [85]

Charles E. Mongrain left Dawson in 1903 bound for Coal Creek in Alaska. [86] In 1907 he was living in Circle listing his occupation as "miner." [87] Following 1910, he returned to the Klondike staking several more claims through the early 1920s. [88] There is no indication of when, or if, he left the country. It appears that Mrs. Mongrain did not accompany him to the Northland.

MURPHY, MRS. FRANK J.

Frank J. Murphy registered scow No. 1672 with the NWMPs at Lake Bennett on May 28, 1898. [89] Shortly thereafter, he filed locations for placer claims in the Klondike. [90] It appears that Murphy was not successful at his mining ventures. By 1905, he had taken a position as the manager of the Northwestern Trading & Transportation Company (NWT&T Co) on Bonanza Creek outside of Dawson [91] Two years later he moved to the North American Transportation Trading Company (NAT&T Co.) in Dawson where he worked as a salesman. [92] Moving up in the company, he was clerk in 1909-10 [93] and finally deputy manager of the Dawson operations in 1911-12. [94]

It appears that the Murphys confined their livelihood to Dawson. However, they, like many other Dawson businessmen were involved with claims on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek. On October 20, 1910, claim notices list Mr. and Mrs. Murphy, along with N.J. Donnihaugh, Alex Campwell, B.J. Rise, Urnie Parsens, M.C Hagerdy and L. Darlington as co-claimants on two 160-acre claims on the left limit of Coal Creek. The claims were located on September 22, 1910 and October 3, 1910 respectively. However, none of the co-claimants filed the location notices. This honor goes to J.D. Dyke, their attorney-in-fact. [95]

These are the only claims in either Murphy's name. Given the business and managerial nature of Frank Murphy's occupation, it would be safe to deduce that the eight co-claimants were grubstaking Mr. Dyke's prospecting. As is the case later described with Frank Slaven and the Dawson Daily News group who grubstaked his efforts.

OLSEN, BESSIE CURRIE

Bessie Currie Olsen [96] was one of the people who came early and stayed late on the creeks. She and her first husband, James H. Curie, staked their first claims in September 1904 on Iron Creek, a tributary of Woodchopper Creek. Over the next several years she staked additional claims on Mineral Creek (1904), Alice Creek (1905), another on Mineral Creek (1906) and one on Woodchopper Creek proper (1906). Following the death of Gus Abramson in 1931, Bessie Olsen bought his claims from his estate. [97] In 1935, she staked yet another claim, "No. 2 Below Kodiak," on Woodchopper Creek.

During the 1930s, it is not entirely clear if she was at her claims or simply hiring others to work them for her. George McGregor, writing to his former partner Frank Rossbach in 1933, comments that "There is a fellow up here now that [Mrs. Olsen] sent up." [98] Whether she was at the claims or not, Mrs. Olsen is among the group of sourdoughs that staked claims and stayed with them for almost three decades.

PATTY, KATHRYN S. (ALSO PATTY, MRS. E.N.)

Kathryn Patty is the wife of Dr. Ernest Patty. She spent summers at the camps during the early years that it operated before World War II. [99] Historical records list her as the claimant for a number of claims on Coal Creek, Woodchopper Creek and Weber Creek. The name listed on the claim notices varies from Kathryn S. Patty to Mrs. E.N. Patty.

PAUL, LUCILE C.

Lucile C. Paul was the second of three daughters of Alexander Duncan and Blanche McRae. The McRae family figured very prominently in both the financial backing of the two dredging companies as well as being named claimants in work done in anticipation of expanding the operations in later years.

POMPAL, LOUISE

In July 1910, Louise Pompal, along with her husband Joseph M. Pompal, were co-claimants in a 100 acre associated claim on Woodchopper Creek, two and one half miles above Caribou Creek. [100] Mr. Pompal was also a co-claimant in a second 80-acre associated claim on Woodchopper Creek, one half mile above Mineral Creek. [101] The reason why Mrs. Pompal is not included in the second claim is not clear from the records. In August of 1910, Joseph Pompal granted his power-of-attorney to William J. Julian of Dawson. At the time, Pompal listed his residence as "District of Alaska." [102]

ROLAND, ANNA

Anna Roland's name enters the picture in 1908 when James Roland, serving as her attorney-in-fact, files for the Discovery Claim on Deer Creek, a tributary of left fork of Colorado Creek in the Coal Creek drainage. [103] This is Anna's only recorded claim. Like many other women appearing in claim records, there is no information showing that she ever came to Alaska.

ROLAND, LILLA

Lilla Roland's name appears in claim records for Ida Creek, a tributary of the left fork of Colorado Creek. On June 19, 1905, her attorney-in-fact, Joe Williams filed a claim with the Circle District Recorder for 20 acres of placer ground called "No. 2 Above Discovery on Ida Creek." [104]

On the same day, Williams, again acting as the attorney-in-fact, filed claims for James A. Roland and Harry Roland for the "No. 1 Above Discovery on Rose Creek" and the "No. 6 Above Discovery" on Colorado Creek. [105]

Of the three individuals, only James appears in any record as having actually been in Alaska and the Yukon. The first mention of him comes in the late 1890s when records list him as a claimant in the Klondike. [106] By 1907, James had moved to Circle where he worked supplying fuel to the community and surrounding camps. [107] He remained in Circle for the next five years returning to his former occupation as a miner. [108]

SELIGMAN, MARGARET MCRAE

One of General Alexander Duncan (A.D.) McRae's three daughters. She married New York financier Walter Seligman who owned 500 shares of Gold Placers Inc. and Alluvial Golds Inc. stock. [109] According to Glen Franklin, Gold Placers, Inc. accountant, Mrs. Seligman spent very little time on the creeks and making only a few trips to the camps. [110]

SLAVEN, EMMA

Frank Slaven filed a number of claims by using powers-of-attorney from his family, as in the case of Jenny Greathouse. Emma Slaven was Frank's step-mother and Jenny's mother (see photo on page 26). On August 16, 1935, she granted her power-of-attorney to Frank Slaven. [111] At the time, she, along with Flora Slaven, [112] J.C. Slaven [113] and Jennie (Slaven) Greathouse [114] lived in Santa Cruz, California. No claims were located in her name on either Coal Creek or Woodchopper Creek; however, Slaven did file claims through these powers-of-attorney in the Ben and Sam Creek drainages.

TOUPAIN, CARRIE

Carrie Toupain and her husband George F. Toupain were among those who came to Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek by way of Dawson in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Clary Craig, the Dawson post office worker who maintained detailed records on when people left Dawson bound for other places, lists Carrie Toupain as leaving for Circle on August 30, 1900. [115] Her husband, George apparently made the move with her since he granted a power-of-attorney to J.E. Kinalley listing his residence as Circle City, Alaska on November 12, 1901. [116]

Polk's Alaska-Yukon Gazetteer lists George Toupain living in Dawson and working as a miner in 1901 and 1902. [117] In 1904, George grants a second power-of-attorney to Alfred Johnson of Circle to stake mining claims on his behalf. [118] Three years later, the couple lived in Circle where they operated a saloon and restaurant business. [119]

The year 1905 represents a minor rush in claim staking on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek when a total of 95 different claims were staked (representing almost 17% of the total claims staked on the two creeks.) This is the highest number of claims staked on the creeks from 1901 through 1949 (n=565) (See Appendix II). The Toupains are part of this rush of individuals moving from Dawson to Circle with claims staked in their names along the way. Although neither Carrie nor George located claims in their own names, on June 9, 1905, Frank Sawyer located the "No. 10 Above Discovery" on Rose Creek in the name of George F. Toupain. [120] On the same day, he located the "No. 3 Above [Discovery]" also on Rose Creek in the name of Carrie Toupain. [121]

WELCH, MRS. JACK (KATE)

Following the death of Fred Brentlinger, his wife Flora sold the Woodchopper Roadhouse to Jack and Kate Welsh. The two must have made an interesting couple. According to George McGregor in writing to his former partner, Frank Rossbach: "A fellow by name of Jack Welch and his wife runs the roadhouse now, or at least she runs it, she is certainly the boss. Welch himself is a pretty good fellow. But different with her. She also has the post office." [122]

Ernest Patty, who later managed the dredging operations on the two creeks described Jack as having a "rawboned frame, his swarthy face, and the cast in one eye which gave him a menacing look [that] would have made an excellent movie heavy." Mrs. Welch on the other hand was "a small, hard-working woman, very proud of Jack." [123]

The story of Jack and Kate is a very touching one that stands out in the annals of Yukon Klondike history. Like many of those living along the extended community that accounted for almost 250 miles stretching between Dawson City and Circle, Jack was active in businesses on several fronts. On one, he and his wife ran the Woodchopper Roadhouse where travelers could get a decent meal and place to sleep. On the other, Jack held the winter mail contract between Woodchopper and Eagle. He would run his team of huskies through the roughest weather to see that the mail got through. Kate served the tiny community of about a dozen trappers and prospectors at Woodchopper as the postmistress from 1932 to 1936 when it was moved to the camp at Coal Creek. It appears however that she was a little over zealous in finding out the local news. When McGregor wrote to Rossbach, he gave fair warning that if "you write to me again and have any sealing wax handy please seal the letter with it." [124]

It is unclear just how many years the Welchs had spent in the North Country. No record has been located for when they arrived. Eventually the isolation and old age possibly combined with Jack's apparent problem with alcohol [125] began to take their toll. By the late 1930s, airplanes were replacing dog teams for carrying mail and Jack lost the contract. During the early years that the dredges operated on Coal Creek and Woodchopper, Patty would hire Welch for emergency trips with his boats but they saw Jack less frequently as time went on. [126] After World War II broke out, most of the people living along the Yukon moved to Fairbanks taking advantage of the high paying jobs afforded by military contracts. The Welchs stayed on at the roadhouse.

Spring on the Yukon can be an exciting time. As the ice begins to break up and move out it frequently jams in the narrower sections of the drainage. This was the case one spring when a huge dam piled up in Woodchopper Canyon, five miles below Coal Creek. Ernest Patty, who along with Jim McDonald from the Alluvial Golds Inc. camp, spent the night in a cabin located at the mouth of Coal Creek, described the break up as:

At about three o'clock in the morning, loud crashing sounds woke us up and we jumped out of bed. The river had gone wild with the crushing force of the breakup. Normally the Yukon, at this point, is less than a quarter-mile wide. While we slept, the water level had risen fifteen feet. Rushing, swirling ice cakes were flooding the lowland on the opposite bank, crushing the forest of spruce and birch like a giant bulldozer. Before long ice cakes were being rafted up Coal Creek and dumped near our cabin.

Then at the same moment we both turned and look at each other. The rapid rise of the river could only come from a gigantic ice dam in Woodchopper Canyon, some five miles downstream. Jack Welsh and his wife lived in that canyon. Their cabin must be flooded and probably it had been swept away. There is no way of knowing if they had been warned in time to reach the nearest hill, half a mile from their cabin. No outside help could possibly get to them now. [127]

As it turned out, the howling of their dogs awakened the Welchs. They found ice water covering the floor of the roadhouse. Jack ran outside and cut the dogs loose allowing them to reach higher ground on their own. Some made it. Some did not. Jack returned with his boat intending to take his wife and make a run for higher ground himself At that point, the bottom floor of the roadhouse was under water and the second floor already awash. As huge cakes of ice slammed against the outside walls, Welch tied the boat to a second story window deciding that it would be better to stay with the cabin until the very last moment because the ice could crush his boat. Jack used a pole in an attempt to deflect ice cakes from hitting the cabin. [128]

As they waited, the water and ice continued to rise higher and higher until it finally stopped and slowly began to drop. This meant the ice dam was beginning to break. Now the ice cakes were coming with increased frequency and force. In the end, both the roadhouse and the Welchs survived. Years later, Ernest Patty noted that "perhaps it would have been more merciful if they had been swept away."

The terror these two elderly people experienced left deep scars. Neither fully recovered from this night of rising floodwaters and crashing ice. Consequently, Mrs. Welch became bedridden. As time passed, people began to comment that Jack was "getting strange." [129]

One frantic night, Jack had a nightmare that the German Army was marching down the ice of the frozen Yukon. He awoke in a cold sweat, trembling. Babbling like a child, he asked his wife, "If they come, will you protect me?" [130]

Later in the night, he grew silent and she thought he had dropped off to sleep again. Once again she heard his voice as he said "I know what's wrong. I'm losing my mind. I'm better off dead. I am going to shoot myself." He rose out of bed and despite his wife's pleas; he dressed, took his rifle and walked outside. A few minutes later he came back in and laid down on the bed reporting "I can't do it. I lost my nerve." About an hour later, he got out of bed again announcing that he "got my nerve back."

As he left the cabin, Mrs. Welch forced her crippled body out of bed and began dressing when she heard a shot. Jack stumbled back inside. He had shot himself in the side, but the bullet had missed his heart. She helped him into the bed, took the rifle so he could not make another attempt. With the aid of two canes hobbled two miles over a winter trail to the cabin of their nearest neighbor, George McGregor.

McGregor hitched up his dogs, placing Mrs. Welch in the sled they returned to help Jack. After giving him first aid, McGregor loaded Jack into the sled making a run up Woodchopper Creek to the mining camp where the winter watchman sent a radio message to Fairbanks. Several hours later a plane arrived and took Jack to the hospital in Fairbanks.

Within a month Jack was up and around again. Nevertheless, the shock was too much for Mrs. Welch. She lingered on for a short time after Jack left the hospital until her tired, old heart finally gave out.

After his wife's death, Jack refused to accept it. He did not attend the funeral, clinging to the idea that she was waiting for him at the roadhouse. When he did not find her there, he went to the dredge camp asking the men if they had seen her, insisting that she was "hiding from me." [131]

Patty tried explaining the situation but could not reach Jack. After he left, they radioed the U.S. Marshal's office in Fairbanks requesting that they come and take him to the hospital.

The next day both Jack and his boat had disappeared.

Over the next few weeks, word started trickling back from villages along the lower Yukon of a mysterious elderly white man sitting in a small boat drifting down the river. Passing boats tried hailing him with no response. Finally, reports came from some Natives hunting on the Yukon delta of a man standing in a boat, shielding his eyes against the harsh western sun, looking out to sea. Jack and his boat floated out into the Bering Sea. They were never seen again. [132]

After Mrs. Welch's death and Jack's disappearance, the Woodchopper Roadhouse was left to the elements. Presently it lies in ruins, the roof caved and the upper story fallen in. Every several years the low-lying area on which it stands is flooded as the Yukon River goes through its annual breakup.

The Gentlemen of the Creeks

MARTIN ADAMIK

According to the 1920 US Census, Martin Adamik [133] was born in Hungary in 1879. He immigrated to the United States in 1906. People who knew Adamik refer to him with one simple adjective, "gentleman." [134]

Like many of the early miners on Coal Creek and Woodchopper, Adamik located claims in both drainages. However, his main activities focused on Coal Creek along Boulder and Colorado Creeks (tributaries approximately 4-1/2 and 7 miles respectively up Coal Creek from its confluence with the Yukon River). In addition, he held claims on several small tributaries of these. His residence cabin is located at the mouth on Boulder Creek. It remains standing. Two claimants inhabit it seasonally today. [135]

It is uncertain when Adamik arrived in the country along the upper Yukon. The first record of his activities comes in 1910 when he, George W. Powers and G. Petrina filed an association claim for sixty acres of placer mining ground on an un-named tributary of Coal Creek. The group named them the "Sun Rise Claims." [136] Four years later, on October 5, 1914, Adamik located an individual claim for twenty acres on Woodchopper Creek that he named simply "Martins" claim. [137] In 1915 and 1916, Adamik filed for two additional claims, one on Rose Creek, a tributary of the left fork of Colorado Creek, and the second on Boulder Creek. [138]

Ten years later, on September 7, 1927, Adamik filed a "Notice of Grouping" with the Circle Mining District recorder. With this, he claimed ownership of the following claims: "No. 1 Smiths on Coal Creek," "Boulder Association," "Number One on Boulder," "Number One on Big Boulder," and the "No. 1 Bench on Coal Creek." Although records do not show how he accumulated these claims, under the mining laws at the time, he was able to consolidate them into a single group specifying that "all assessment work may be performed at a point or points on any of said claims if in the Judgment of the undersigned said work will inure to and be for the benefit of all of said claims as a whole." [139] In other words, he was able to do assessment work on any or all of the claims at the same time maintaining the validity of all the claims.

By the mid-1930s, people described Adamik as an old man. Most likely because at the age of roughly 56, his chosen course in life had weathered him considerably. [140] To a young boy like Dale Patty, he must have seemed ancient. In addition, living alone in his little cabin made him seem even more exciting. Patty describes him as "a total loner" with one very distinguishable characteristic; he talked "like a machine gun. When you came to his house, he'd talk to you all day long, like a machine gun." [141]

As a young boy, growing up at the mining camp, Patty made it a point to visit Martin three or four times a year. In describing one such visit, he notes that:

You walked in that [cabin], he was usually lying in bed or sitting in a chair [with] a beautiful garden outs back, immaculate. Weeded and so forth. And he had a little sluice box about 500 yards up that valley there. He would use it to get just a little bit of gold to buy what he needed and the rest of it was either by a moose or by the garden. You walked into his house and he had this thick, thick Austrian accent. And the machine gun would take off. [142]

While Patty describes it as a thick Austrian accent, Glen Franklin, the accountant and bookkeeper for Gold Placers Inc. and Alluvial Golds Inc. explained that Adamik learned to speak English by reading Shakespeare. Because of this, his speech always had a slight Shakespearean twist to it, in addition to the thick Germanic accent. [143]

During the time he worked for Gold Placers Inc, Franklin and his wife would occasionally walk over to Adamik's cabin in the evening spending time visiting. One fall, when the company closed up the camp for the winter, they took a small radio over to the lonely little cabin to keep Adamik company over the long, cold winter. At first, Adamik tried to tell them that he did not need it. He eventually relented and said his good-byes to the couple, who just happened to have ordered a new battery because they knew they would be leaving it with Martin for the winter. [144]

The following spring, when they returned to Coal Creek for the new mining season, Franklin dropped in on Adamik to see how he had faired the winter. Much to his surprise, Adamik was jubilant and bubbling with excitement about "the man talking in the box." Adamik shared his disappointment however because even though he tried talking to him, the "little man never answered" back.

The few people still around who remember Martin Adamik, describe him as a kind, quiet, unassuming, gentle old man. A meticulous individual, people remember visiting Adamik's cabin with his immaculately cared for garden surrounding it. Adamik eked out a meager living from his claims, taking only enough gold to buy the supplies that he could not either grow in his garden or get from the land by way of an occasional moose or caribou. [145]

The sad end to his story came in 1958 when Dale Patty and several members of the mining crew returned to the dredge camps for another season. On April 9, 1958, Patty, Suzy Paul and Willie Juneby landed at the Woodchopper airstrip. The company already had plans to work the ground on Woodchopper for the season letting the Coal Creek dredge stand idle. The men prepared the big International TD-24 tractor with its dozer blade along with a sled to haul supplies and headed up and over the road toward Coal Creek camp. Within 3/4 of a mile from their destination, the tractor coughed, sputtered, and stopped. It had run out of fuel. This forced the men to walk the remaining distance to the camp through waist-deep, heavy, wet snow. Patty broke trail for the first 300 yards after which they alternated as they slowly made their way downhill. Finally arriving at the mess hall, Patty reported that it was "the greatest thing I had ever seen." [146]

The men then carried half-full five-gallon buckets of diesel fuel back up the trail to the stranded tractor. They continued ferrying fuel back to the tractor until almost 1:00 in the morning when fatigue finally forced them to stop for the night. Reluctantly they drained 50 gallons of water from the tractor's radiator to prevent it from freezing in the sub-zero temperatures. [147]

The next morning the men carried an empty drum up the trail to the tractor to use to melt snow to replace the water they drained the night before. Finally, after much work and many trips back and forth through the deep snow, the tractor coughed back to life and they continued on their way.

Upon arriving at the camp, they first topped off the tractor's fuel tank, then set out across the valley to Adamik's cabin at the mouth of Boulder Creek to make sure he made it through the winter. In Patty's words:

When we walked into the place, Martin was in bed and he was looking bad. But he was talking. The machine gun started again. This went on for an hour, hour and a half; I didn't keep track of the time.

And then, I'll never forget this as long as I live, he looked up to me and said, "Dale, I think I'm through talking now." And he was dead. He was dead. [148]

Sitting in the small cabin, in the dead of winter, with his lifelong friend's body, Patty had to make some decisions about what to do next. Hoping to find instructions Martin may have left for just such a situation, a brief search of the cabin proved fruitless. [149] Finding none, they took matters into their own hands.

Winter on the Yukon is not a time when one can easily dig a grave. Therefore, Willie Juneby sewed Martin's body into a piece of canvas as a burial shroud. Suzy Paul went back out to the tractor and cut a shallow trench in a snow bank. They then laid Martin's body in the snow piling it on top to help keep him cold. On a small knoll nearby, Suzy then took the tractor and using the blade, pushed the snow off the ground and started to dig a grave into the frozen soil. Each day, after working at moving buildings and machinery from the camp at Coal Creek across the hill to Woodchopper, Suzy went back over to the little cabin on Boulder Creek. There, he dug a little deeper as the sun slowly melted the exposed soil. He finally reached a depth of about eight feet into the frozen earth. Then, Dale, Willie and Suzy all went back over to the cabin, dug Martin's body out of the snow, and placed him in the grave. After filling it in with frozen dirt, they piled rocks high on top to keep the wolves away. [150]

Martin Adamik, the Hungarian miner who spoke like a character from a Shakespearean play, had come to the creeks before 1910. He lived a life of solitude for almost fifty years in his little cabin at the mouth of Boulder Creek. Now, from his grave nearby, he remains in silent vigil over his claims.

BERAIL, PHIL

Phil Berail came north in 1904 [151] at the age of 24. Initially settling in the Dawson area where he worked until August 14, 1908 when he left bound for St. Michael on the Bering Sea [152] Three years later he was working as a logger for the Copper River Lumber Company in Valdez. [153] He eventually migrated back to the upper Yukon River where he prospected, mined and trapped the country between Eagle and Circle, primarily throughout the upper Charley River area for the next five decades. Today, historians credit Berail with building a number of cabins on tributaries of the Charley River. Among them are several line cabins figuring prominently in the survival story of Lt. Leon Crane, a U.S. Army Air Corps aviator who survived a mid-winter crash and walked out of the country almost three months later. [154]

Statements like: "He was the toughest man I ever knew. He was tough as nails," [155] or "He was so tough you couldn't kill him with a club," [156] are often used to describe Berail. Apparently immune to physical discomfort, Dale Patty once stated that Berail "must have had all his nerves disconnected at birth." [157] Dale's father Ernest Patty, who first hired Berail as the hydraulic foreman at Coal Creek, once described him as, "completely disdainful of danger or physical discomfort. When the weather turned cold, his crew was all bundled up. Phil would be working with them bare-handed, his shirt open over a mighty chest." [158]

There is little information regarding Berail's life on the Yukon before the mid-1930s when the dredges were put on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek. Ernest Patty hired him as hydraulic foreman for the Gold Placers Inc. mining operations. [159] He was in charge of the ditch, the various pipes and water systems used to wash the muck from the overburden. He also served as the winter caretaker for the operations for a number of seasons. [160]

Berail kept his dog team at the camp basing some of his trapping out of Coal Creek. Each winter after the crews shut down the operation for the season, he would lash a small outfit of grub and supplies on his sled and head up the canyon toward the headwaters of the Charley River where he would spend most of the winter. He returned to the mining camp on occasion to make sure everything was intact. The next spring, when the crews returned for another season they would often be overheard saying to one another "I wonder if Phil made it through the winter?" And just like clockwork, Berail would appear in camp, "grizzled and weather beaten, but exuberant." Ernest Patty notes that "seeing him come along the trail with his dog team, he always reminded me of a figure straight out of some northern myth." [161]

Hard work was something that Berail never thought about twice. In his book, North Country Challenge, Patty mused that "The first year I made the mistake of suggesting that he take a couple of days off to rest up. The disdainful look he gave me would curl your toes, and the next morning he set such a pace at work that his crew, softened by a winter of idleness, could not keep up." [162] Years later, Patty's son Dale had taken over managing the mines. He tells several tales of Berail and injuries he sustained at the mines.

One day Phil came into the camp office holding his hand against his chest wrapped in an old oily, dirty rag. Dale asked what had happened. Berail told him he had cut his finger. Patty took his hand and slowly unwrapping the piece of cloth found that not only had he cut his finger, he had cut it off!

Trying to convince Berail to let him call an airplane to take him to the hospital in Fairbanks proved futile. He would have nothing to do with it. Instead, he said, "I have a clean rag over in the cabin. I'll just wrap that around it and it will be all right." Patty was able to get him to compromise into letting him put some antiseptic on the wound and bandage it properly. Shortly afterward, Berail went back to work!

A second episode found Dale working in the office again when Berail came in clutching his arm to his chest again. This time, Patty noticed what appeared to be an extra "bend" in the lower arm that should not have been there. When asked what happened, Phil replied in his gruff, gravelly voice, "I guess I broke my arm." Again, Dale tried to convince Berail to allow him to call in a flight from Fairbanks to fly him to the hospital so he could get it set and properly cared for. Typical for Berail, his comment was "Hell no, it's just a little break an it will be fine in a week!" Again, Berail would have nothing to do with it. [164]

He went back to his cabin, got a piece of cloth, fashioned a sling to support his injured arm and went back to work, again! Several days later, the sling was gone and Phil was back at work. This injury never healed properly. From that time forth when Phil drank a cup of coffee, he used both hands to lift the cup. [165]

Not only was he physically tough, Berail could also drink with the best of them. In fact, he could handle his liquor better than the best of them. One night, Glen Franklin, the company accountant and postmaster at Coal Creek, went down to Slaven's roadhouse to meet the steamboat and retrieve the mail. He returned to the camp at around 2 o'clock in the morning to find Berail waiting anxiously for a package he was expecting. The package contained a bottle of rum. Not just any old type of rum however. Berail had a special liking for 180 proof rum!

Not wanting to appear un-hospitable, Berail invited Franklin into his cabin for a drink. Taking two "generally clean" glasses off the shelf, he poured each a healthy "snort." Berail picked his up, put it to his lips and drank it down as though it was nothing more than a glass of water. Franklin, figuring it could not be all that bad, took a healthy swallow and just about gagged. He was certainly not used to drinking the same way the old timers were. [166]

Berail was one of those men who lived all his life on the creeks, did not see a need for anything new, and especially did not need help from the government. The first time he saw the company was deducting social security taxes from his paycheck he stalked into the office demanding to know what "this social security monkeyshine" was all about. Ernest Patty explained the new law to him.

"I don't want it," he said.

When he found that the law demanded the deduction he stormed out, tossing over his shoulder, "We're getting to be a nation of damned softies." [167]

Phil Berail worked for Gold Placers, Inc. and Alluvial Golds Inc. until August of 1955. By this time, he was 76 years old, well past the time when most men retire and start to enjoy a more leisure lifestyle. That month, while riding in the back of the company's 2-1/2 ton truck down to Slaven's Roadhouse to pick up supplies, Dale Patty, who was driving the truck, told his riders that he had to pull forward and they should stay put. Phil either did not hear the warning or with his usual stubbornness chose to ignore it and jumped out of the truck just as it started to move suffering a severely fractured hip as a result. [168]

This time there was no way that Berail would be able to say, "just leave it alone and it will be all right." They summoned a plane from Fairbanks. Dale drove Phil over the hill to the Woodchopper camp to meet it. Patty later commented that owing to the type of man Berail was, "If we had left him alone, he would have probably walked the six miles to [Coal Creek] camp." [169]

Considering it is approximately 12 miles from Slaven's Roadhouse to the Woodchopper airstrip, all on a rough dirt and gravel mining road, in a heavy truck with stiff suspension, the pain must have been excruciating.

By this time, Phil was no longer living at the camp full-time. He had a cabin at Fortymile, a mile or two upstream from the confluence of Eureka Creek and the Yukon River, on the right bank, approximately 10 miles downstream from Woodchopper Creek. [170] Following Phil's injury, someone from the camp had to go down to pull his fishwheel out of the river so it would not be destroyed by the ice. They also had to get his cabin in shape for fall and care for his dogs. Dale Patty informed his wife Karen that he would be going down river with a flat-bottomed boat to take care of it.

Fall days on the Yukon are short and by that time of the year, generally cold. Karen Patty, in her autobiography comments:

I didn't like the idea of [a] small boat, heavy clothes, jumpy dogs (strangers to the men), and the river. Dale and Tim [171] left after 10:00 am, not giving them much time to return before darkness. They couldn't (safely) run the boat after dark. [172]

The two men arrived at Berail's camp and set about pulling the fishwheel from the river and preparing the cabin for winter. Then they had to deal with the dogs. This was not a task that Dale looking forward to undertaking. Many trap line dogs of the day had mean tempers and were not used to having strangers working with them. Berail's dogs were not at all happy about having strangers working around their camp. The possibility that they just might have to shoot the dogs rather than take them back to camp had crossed the men's minds. [173]

Instead, they had an idea. The dogs looked hungry so if they fed them then maybe they would settle down. Berail, like everyone else working a fish camp along the river, dried his salmon to preserve it. When eaten, dried salmon reconstitutes and swells. Therefore, Dale and Tim fed the dogs dried salmon. And fed them. And fed them. They fed the dogs all they could eat and then gave them some more. [174]

Dale gave his .30-06 to Tim with orders that if anything happens, shoot the dog! Then he moved in with a leash to take the first to the boat. Luckily, their idea about feeding them worked. They were so full they could hardly move. Taking the first dog to the boat, Dale tied it with a line so short it had to lie down on the bottom. They put the second aboard and tied it the same way, then the third. Finally, they were ready to head back to Coal Creek. [175]

Karen Patty continues with her description of the day:

After dinner that night, I put all 3 boys to bed. [176] I was concerned because it looked like they couldn't possibly make it home today. Sally [Murray] [177] came to the house to tell me not to worry. About 8:30, pitch dark, I heard the noise of the big truck coming back from the beach. Was I ever glad to see Dale! [178]

All those involved were happy that the incident was now behind them. They gave the dogs to the Paul family who lived at Snare Creek for their use during the coming winter. Later Dale noted, somewhat in relief, "I always wondered what would have happened if one of those dogs got loose on the trip up river." [179] Luckily, the men did not have to find out.

Berail came back to work at the mines after spending the winter season recuperating. Several years later when the dredges closed down, he moved to Circle where he continued to live until the winter of 1960 when he was admitted to St. Joseph's hospital in Fairbanks. [180] Phil Berail passed away on January 22, 1961 at the age of 82 after having spent 57 years in Alaska, most of it living the life of a prospector, miner and trapper. [181]

SAMUEL DOWNS HARVEY

Samuel Downs Harvey was one the thousands and thousands of people from around the world who left their jobs, their families, and their homes to join the great gold rushes to Alaska and the Klondike gold fields in the late nineteenth century. Harvey hailed from New Castle, Indiana where he had lived since his birth in 1854. Prior to leaving for the gold fields, Sam worked as a clerk in a hardware store. When he headed north, he left behind a wife Elizabeth "Libbie", and three children: Augusta "Gussie" May, Walter Benjamin, and Ruth Ada.

Sam grew up hearing stories about the California Gold Rush of 1849. In fact, his uncle Sam Downs, his namesake, came back with enough gold to buy a farm and build a nice brick house in Hillsboro, Indiana. When news of the gold strikes in Alaska arrived, Sam wanted more than anything else to go after it and to be able to build a comfortable home for his beloved wife and children.

|

Leaving home in 1895, Harvey set out on an expedition that was to last for only a couple of years at most. Little did he know that he would be gone for twenty-seven years instead. Traveling through Chicago and Seattle, he finally landed in Juneau where he obtained a grub stake on Gold Creek, immediately east of the town.

According to family records, Harvey was headed back to Indiana in either late 1897 or early 1898 when he received a letter, posted from Indiana many months before, informing him of the death of his beloved wife Elizabeth the preceding October. The letter continued telling him that his son Walter and daughter Ruth were in good hands (his daughter Augusta had married in December 1897) and the family property "had been disposed of." Several years later, in a letter to his family, Sam wrote: "Dumb with grief, I decided - in a moment - turned on my heel - in a sand spit at Dyea Harbor, where I had gone to take passage south, - turned my face northward - not knowing where - but believing that you children were better placed than anything I could do for you." With that, Sam Harvey joined the rush to the Klondike.

On June 9, 1898, the North West Mounted Police registered Harvey and three companions: G.W. Wilkenson (Pittsburgh, PA), M. Seger (Pittsburgh, PA) and William Moier (San Francisco, CA) as the occupants of boat #13030 before they headed down Lake Bennett on their way to the gold fields. Like many who ventured to the Klondike, upon their arrival Sam and his companions found all the ground already staked.

Soon after word reached Dawson announcing that gold had been discovered on the Seward Peninsula on the western coast of Alaska. Harvey and at least one companion, a man by the name of William Speddy, headed down the Yukon River and joining the Nome gold rush. Although Sam's letters to his family mention finding some gold, they tend to be more descriptive of the prices, people, and conditions at the new camp. Apparently, once again, Harvey failed to strike it rich in Nome.

Reports continued to come of good gold placers along the upper Yukon River, particularly between Dawson and Circle, Alaska. Sam left Nome heading back to Dawson in 1901 stopping for a time in Circle City. Eventually, he was among the first people to file claims in the drainage when, on August 7, 1902, he filed for the No. 2 claim on Alice Gulch.

Over the next nineteen years, Harvey's hard work provided good care for his children who eventually attended college. At the time, a college education for anyone was considered outstanding, but to have all three of his children graduate was quite an accomplishment. His two daughters, Augusta and Ruth became teachers and his son Walter a medical doctor.

Sam left the creeks in 1923 returning home to Indiana and his family. Four years later, at the age of 73, he and Walter embarked on a summer-long expedition back to the gold fields. The two men met in Chicago and from there traced Sam's original trip to the Klondike and on down the Yukon to his camps on Woodchopper Creek and Coal Creek. On the way, Sam introduced his son to the colorful figures he had known during his gold rush days, shared sites and experiences that few in the Lower 48 could imagine. From there, they went to Circle and on to Fairbanks, Alaska where, unfortunately for the reader, the narrative ends. [182]

JOHN HOLMSTRUM

When word of the gold discoveries in the Klondike hit outside newspapers, men and women from around the world dropped what they were doing and flocked to the Yukon River. Among them was a twenty six-year old Swedish man by the name of John Holmstrum who arrived with the Klondikers of 1898. [183]

According to the 1910 US Census, John Holmstrum was living and working claims on Mineral Creek, a tributary of Woodchopper Creek approximately four miles upstream from its confluence with the Yukon River. By this time, he had been in the country for over ten years. Holmstrum staked his first claim on Mineral Creek, a tributary of Woodchopper on November 27, 1901 when he filed for twenty acres of placer ground naming it "No. 2 Above Discovery." [184]

Over the next decade, Holmstrum continued to stake claims on Woodchopper Creek including when on December 1, 1910 he, along with M. McLeod, Dan Crawley, E. Vass, William F. Stair, Charles Boyle, John Corcoran, and W. Lewis filed notice claiming 160-acres. Located approximately one mile below the confluence of Woodchopper and Mineral Creeks, they named it the "Mineral Association." [185]

In 1913, while on a trip to Dawson, Holmstrum happened to meet a young greenhorn by the name of Frank Rossbach who was working as a bartender in the Occidental Hotel. Apparently Holmstrum had already heard about Rossbach and knew he was looking for a mining claim. Swedish born Holmstrum hit it off with young Rossbach who had left his native Germany several years earlier.

Holmstrum had a problem with alcohol. He enjoyed it excessively much. Rossbach on the other hand, was a teetotaler. Holmstrum invited Rossbach to be his partner with his claims on Woodchopper Creek in exchange for his help getting him off the booze. Rossbach agreed to the offer and the two men set off down the Yukon toward a partnership that would last for the next decade. [186]

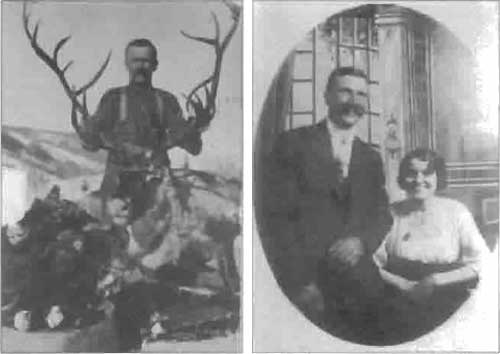

|

| Left: John Holmstrum (undated photo taken between 1913 and 1923). Photo courtesy of Dietrich Rossbach. Right: John Holmstrum and his wife in Sweden after he left Woodchopper (circa 1924-35). Photo courtesy of Dietrich Rossbach. |

The following year, Holmstrum filed on the "Comet" claim on Woodchopper northeast of the "Discovery" claim at the mouth of Iron Creek. He and Rossbach made the discovery and accomplished the necessary location work between November 6 and December 10, 1914. During that time, they successfully excavated two shafts, each nineteen feet deep, to bedrock where they encountered the paystreak. [187]

Holmstrum decided to leave the country in 1923 returning to his native Sweden where he eventually married a woman from back home. As evidenced through letters now in the possession of his partner's family, he stayed in touch with his friends from the creeks over the years including sending photographs of he and his wife. [188]

GEORGE McGREGOR

George McGregor was born in Missouri on November 23, 1887. He enlisted in the US Army on September 26, 1918 during the latter days of World War I. While he was in boot camp the war ended and he was honorably discharged on January 9, 1919. According to information located at the Eagle Historical Society and Museums, he came to Alaska right after his discharge. [189] His cabin on the Yukon River is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Yukon-River Lifeways thematic nomination.

Upon his arrival in the country, McGregor partnered up with Frank Rossbach on Mineral Creek. When Rossbach left for Germany in 1926, McGregor remained to work their claims. In August of 1927, Sam Harvey notes in his "Alaskan Travelogue," that McGregor's "partner" had returned to Germany to find a wife and was expected to return to the creeks.

George McGregor left his cabin on Mineral Creek in the late 1930s after he sold his claims to Alluvial Golds for their dredge. He moved into a new cabin on the banks of the Yukon River between the mouths of Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek. He kept a diary that, although each entry is almost cryptic in it's simplicity, when taken as a whole, the reader can see the cycles of the seasons as they pass by year after year. McGregor was one exception to the many other miners in the area who frequently made trips to Circle or Eagle. Through his diary he only records one trip to Circle in nearly 30 years!

But he does record seeing others who lived in the region making trips up and down the Yukon on their way to town. [191]

McGregor left the creeks in July of 1954 and moved to Eagle. After spending several years in Eagle some serious "sores" developed on the bottom of his foot. When the injuries failed to heal, friends convinced him to see a doctor in Fairbanks. The doctor wanted to amputate. He said "No. I want to die with my feet." He then went to the Veteran's Hospital in Vancouver, Washington where again the suggested treatment was amputation of the foot. Again, McGregor refused and said, "Fix me up the best you can so I don't suffer." The doctors did the best they could and he moved into the Wilcox Boarding Home in Vancouver.

In the afternoon of March 4, 1966, at the age of 78 years, George McGregor's heart gave out and he too crossed his last summit. He is buried in the Willamette National Cemetery in Portland, Oregon. [192]

|

| George McGregor (circa 1913-26). Frank Rossbach Collection, photo courtesy of Dietrich Rossbach. |

FRANK ROSSBACH

Frank Rossbach took a circuitous route from his native Germany to get into the country along the upper Yukon. Born in 1891, he worked as a baker's apprentice as a young man. After working for several years he decided that he was not cut out for a sedentary lifestyle and wanted more adventure out of life. Making his way to Hamburg, he hired on as a cabin boy on a tramp steamer setting off to see the world. [193]

From Hamburg, Rossbach circumnavigated the globe, not once, but twice. His children remember him telling of his adventures in such exotic places as Japan and Borneo. During his second trip around the world, while docked at Tacoma, Washington, Rossbach heard stories of the gold fields in Alaska and the Yukon. Still seeking more adventure, he approached the captain of the ship with a request to be paid off and allowed to "jump ship." The captain explained that normally the company paid the crew at the end of the voyage when they returned to their homeport. Since Frank was apparently serious about his desires and had been a good employee to that point, the captain made a deal to pay him and let him remain in Seattle when the ship set sail if he could find someone to replace him. [194]

|

| Frank Rossbach (circa 1913-26). Frank Rossbach Collection, photo courtesy of Dietrich Rossbach. |

Rossbach spent several days, and nights, scouring the saloons on the Tacoma waterfront trying to find someone willing to take his place on the steamer. Eventually he succeeded. The captain paid him in full for his services. When the steamer set off into the Pacific, Rossbach was setting out on yet another new adventure.

Because he did not have enough money to pay for his passage to Alaska, Rossbach worked as a short order cook for a while. Eventually able to buy a ticket north, he set out for a trip through the Inside Passage to Alaska. He landed at the gold rush port of Skagway having arrived almost a decade after the great rush of 1898-99 but still finding many of the same sites that greeted the earlier argonauts.

Rossbach made his way from Skagway to Whitehorse walking the rails of the White Pass & Yukon Railway instead of buying a ticket. After arriving at the northern terminus, he joined up with several others building a boat and floating down the Yukon finally arriving in Dawson City in summer of 1913.

In Dawson, Rossbach was successful at getting a job as a bartender in the Occidental Hotel. There he had the opportunity to meet some of the old timers who had come north with the Rush of '98 and heard their tales of climbing the Golden Stairs of Chilkoot Pass.

Unfortunately for Rossbach, as well as most of the others who arrived in the Klondike after the initial gold discoveries, all the ground around Dawson was either already staked, under the control of large mining companies or plain worked out.