|

YUKON-CHARLEY RIVERS

The World Turned Upside Down: A History of Mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, Alaska |

|

CHAPTER FOUR:

COAL CREEK OPERATIONS

GENERAL ALEXANDER DUNCAN (A.D.) MCRAE

In 1933, General A.D. McRae from Vancouver, Canada decided to venture into gold mining. He saw gold mining as an industry that showed promise for weathering the world-wide economic depression and through his personal investigations determined that because of international tax structures, the best places to mine for gold were British Columbia and Alaska. McRae brought in some of the foremost experts in the fields of geology and mining to assist in his venture. These included: Ira B. Joralemon, an internationally known consulting geologist with decades of experience; Charles Janin, a renowned dredge engineer and expert who worked throughout the world; and Ernest N. Patty, dean of the School of Mines at the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines. Of the four men, McRae was the only one not viewed as an expert in the fields of geology and mining — but then, he was the one financing the operations and he was an expert at managing businesses.

McRae first came into Patty's office in Fairbanks in 1933. Patty described him as a big man who looked "as if he had force and brains." [1] Patty's youngest son Dale describes McRae from the standpoint of a young boy meeting a giant of a man:

He was a large man with a large stomach, but carried himself straighter than any man I have ever seen. At first, he scared me silly because he was so imposing, but then we got to be real friends (I guess because he had no sons) and he treated me like royalty and taught me many things. [2]

McRae was born in 1874 on his family's farm in Glencoe, Ontario. His life would take him from his humble beginnings to becoming one of Canada's financial, business and political leaders.

At the age of 24, in 1898, he had managed to save $1,000. This he invested in a very successful banking venture in Duluth, Minnesota where he turned his small investment into $50,000. Not only did McRae bring new capital back to Canada he also brought his new wife, the former Blanche Howe of Minneapolis, with him as well. They would eventually have three daughters, Blanche, Lucile, and Margaret ("Peggy"). All the McRae women became shareholders in his ventures on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek in Alaska. [3]

Using this new capital, he, along with additional Canadian associates, purchased 500,000 acres of Saskatchewan farmland from the Canadian government for $5 per acre. They increased their holdings by making purchases from railroads and others until they eventually controlled 5,000,000 acres. This in turn they sold for a profit of $9,000,000. By this time, McRae ranked as one of the wealthiest men in western Canada. Through a brilliant business career, embracing such varied interests as lumber, fishing, whaling and land speculation, he showed extraordinary organizing abilities. Applying his organizational skills and business methods to the fields of politics and war brought him even more success. [4]

McRae continued focusing his attention further west. He was hired to oversee harvesting a vast quantity of timber in British Columbia. To accomplish this, McRae established the Canadian Western Lumber Company, one of the largest in British Columbia. [5] As an indication of his business acumen, he formed the company to buy the timber he was supposed to liquidate thus capitalizing on it all the way around. To support his timber operations, McRae built the Fraser River Mill near Vancouver. Here he milled lumber for building way stations and other facilities along the route of the new Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad through northern British Columbia. At that time, it was the largest lumber mill in the world. [6] As a result, McRae was paid to cut the timber while his own company bought it to transport it to his mill where it was milled into lumber to expand his railroad.

In addition to his lumber interests, he established and developed Wallace Fisheries, one of the most important fishing and whaling companies, in British Columbia. Through his innovations, McRae modernized the Canadian fishing industry by financing the first salmon cannery to clean and pack the fish with the "Iron Mike" instead of hand labor. He also financed the first "mother ship" to cut the expenses associated with whaling. In both cases, he saw that others would soon imitate his methods, thus cutting into his large profits, so he sold out after the first few good years. [7]

When World War I broke out, McRae went to Europe as an officer in a Canadian regiment. By the war's end, he had advanced to the rank of Major General assisting Britain's Minister of Information, Lord Beaverbrook. [8] For his services, the British crown offered McRae knighthood, which he declined. [9] For the remainder of his life he was known as his military rank rather than by his own name. Even today, six decades following his death, family and associates still refer to him as "The General."

|

| Figure 1: General A.D. McRae (wearing the dark suit on the right) meeting with members of the Conservative Party, 1930. Mrs. McRae is holding the bouquet. (Photo courtesy of the Vancouver City Archives) |

McRae gravitated to politics after the war. His first large-scale venture in British Columbia was the formation of the Provincial Party, which captured only one seat in the 1924 election but split the Conservative vote so badly that the Liberals were victorious. By 1927, General McRae became a Member of Parliament (MP) representing the Vancouver North district. Apparently forgiven by the Conservatives, he organized the National Conservative Convention and through his efforts over the next three years brought the Tories to power in 1930 with the election of Mackenzie King as Premier. [10] Although this move cost him his seat in Parliament, the following year he was rewarded for his efforts with a lifetime appointment to the Canadian Senate. [11]

McRae was in the habit of bringing the best individuals he could find into his operations. Ira Joralemon described him in 1931 as "well over 50, nearly bald, of medium height and build, and handsome." Several months earlier, McRae had taken a fall on the icy steps of the Parliament building in Ottawa and cracked his skull. Joralemon noted that "he moved carefully [thereafter] but his judgment was unimpaired." [12]

In the summer of 1933, McRae and Joralemon, both convinced that the price of gold would be rising in the near future, met with Ernest Patty to examine properties in Alaska. The pair approached Patty because of his familiarity with most of the mining districts in the Territory through his 11 years of teaching at the College. In addition, he had examined several of the properties that interested them. Patty himself also took an active interest in developing mining operations in Alaska.

After spending time pouring over notes and maps depicting the properties that interested McRae and Joralemon, McRae informed Patty that "If I find a mine, I want you to operate it for me." Patty notes in his autobiography that "I did not know at the time how quick McRae was in making decisions. I just thought it an odd way of saying 'thank you' for the information I had given them." The following summer (1934), McRae and Joralemon were back in Alaska, this time they employed Patty to spend a month traveling with them looking over properties. [13]

During the summer of 1934, McRae, Joralemon, and Patty examined four mining properties in hopes of finding one with enough potential for developing a profitable lode mining operation. These included the following sites:

(1) The Cliff Mine near Valdez. Here, miners had followed the mineralized vein 365 feet down where rich ore lured them to extend a drift out under the sea. While drilling a face, seawater began to seep into the workings. When they foolishly blasted, the sea came rushing in flooding the lower works effectively closing the mine.

The McRae, Joralemon and Patty team thought that with modern high capacity pumps, it would be possible to empty the water from the mine sufficiently to grout the tunnel with cement. After hiring an expert from San Francisco with experience in wet mines, the venture proved a failure.

(2) Beauty Bay, 75 miles west of Seward on Nuka Bay. This site showed low assay values and large quantities of iron pyrite (fool's gold) and some galena.

(3) Ester Dome, near Fairbanks. Here, Patty developed two different tunnels following mineralized veins for use as part of the School of Mines curriculum. Early work averaged about $50.00 of gold per ton. However, before long the vein "pinched out" and the college abandoned the venture.

(4) Quigley Properties at Kantishna. [14] The mines that Joe and Fanny Quigley had been working showed potential as silver mine. McRae invested $40,000.00 in tunnels and surface trenches to explore the extent of the ore body. Unfortunately, although it looked promising at first, the additional work only revealed lower grade ores. This, coupled with the long distances to reliable transportation to get ore to market, ended this venture as well. [15]

After four failures at finding a suitable lode mining property, the group turned its attention to finding an area showing promise as a placer deposit. Patty brought up a tributary of the Yukon called Coal Creek where "pick and shovel" miners had been able to scratch out a "scanty" living for almost 35 years. Patty thought that from signs he had seen on previous visits to the area, with mechanical mining (i.e., dredging) the gold bearing gravels might be mined profitably. [16]

McRae offered something the "pick and shovel miners" did not have -- money, and lots of it. [17] Because of his personal fortune, he was able to bankroll the initial operations at Coal Creek, turning a profit almost immediately. Through McRae's keen business sense, coupled with the high caliber of individuals he had working with him, he expanded the operations into Woodchopper Creek the following year, again turning a profit right from the start. McRae, Patty, Janin and Joralemon pulled off what one mining historian has labeled "an exceptionally well-planned, carefully prepared dual enterprise that showed Alaska dredging at its best." [18]

COAL CREEK OPERATIONS

After examining the four lode mining locations and not seeing anything with promise, McRae, Joralemon and Patty visited the workings at Coal Creek and were favorably impressed with what they saw. Consequently, they optioned several miles of ground from the claim owners.

Several weeks later, Patty returned to Coal Creek with a churn drill and a crew to prospect and evaluate the property. The crew put down a series of drill holes at one hundred-foot intervals across the valley floor, drilling through muck and frozen gravel until penetrating bedrock. These drill lines, spaced one thousand feet apart up and down the valley, gave a three dimensional display of where the gold was concentrated among the alluvial gravel. To check the results from the drilling, they sank several prospect shafts between the drill lines. Combined with promising results from the exploratory drilling, the price of gold went up from $20.67 to $35.00 an ounce, just as McRae had suspected it would.

Based on their findings at Coal Creek, McRae offered to match Patty's university salary and to give him an interest in the mine if he agreed to manage the operation. Patty discussed it with his wife Kay and then tendered his resignation from the college, effective at the end of the 1935 school year. Unfortunately, his resignation resulted in hard feelings on the part of University President Dr. Charles E. Bunnell. Their friendship took three years to heal. [19]

When he accepted McRae's offer of running the operation at Coal Creek, Patty did not realize the full extent of his employer's management style. As it turned out, in Patty's words,

Once [McRae] gained a favorable impression of a man, he handed the job over to him, lock, stock, and barrel. He also stood behind whatever decisions were made. I was unused to such sweeping authority. But by that time, I was in it up to my neck. It was sink or swim. [20]

Based on Joralemon's interpretation of the prospecting and production records that Slaven had dating back to the early 1900s, he estimated that the upper claims contained 1,600,000 cubic yards of gravel, averaging $1.10 per yard at $35.00 an ounce. The uppermost 5000 yards, he estimated contained 800,000 cubic yards averaging $1.98 per yard. At this early stage of the operation, he was not able to provide a good estimate of either the yardage or value of the ground comprising the lower claims. He calculated that, taking into account all the usual expenses associated with a placer mining operation, the properties at Coal Creek had a potential to turn a profit of $1,360,000 over a six-year life. At this point, the group still had not decided on exactly what the best approach to mining the placers would entail. Joralemon suggested using several drag lines (the least expensive means of moving a large amount of gravel) or possibly installing a small dredge. [21] He estimated the cost for draglines at $20,000 each and a dredge approximately $100,000 to $150,000. The advantage of a dredge would be that they could move a much larger amount of material in a shorter amount of time. [22]

During the fall and winter of 1934-35, the group made the decision that the best way for recovering the gold at Coal Creek was to use a dredge. McRae brought Charles Janin, the world renowned dredge expert, to assist with determining what type of dredge would best suit the conditions and size of the operation planned at Coal Creek. The company sent the following specifications to several dredge manufacturers for bids: [23]

|

| Alaska Road Commission (ARC) grader at work on the Coal Creek Road approximately 1-1/2 miles above the Yukon River. NPS Photo, Bill Lemm Collection. |

1. Standard California-type bucket and stacker dredge.

2. 4 cubic foot, two piece buckets, inside and outside lips of manganese steel.

3. Steel pontoons, all welded hulls. The pontoons were to be bolted together for easy take down.

4. All-steel superstructure, mostly bolted.

5. Housing steel frame and corrugated iron, framed in such a manner that an inside lining of wood or other material can be added if desired.

6. Dredge capable of digging 14 feet below water level and carrying a six-foot bank.

7. The draft is not to exceed 3.5 feet, completely loaded.

8. Diesel drive, with alternate quote for a diesel-electric plant to be on board the dredge, purchaser's choice.

9. Dredge to be designed so the ladder may be lengthened to dig 20 feet below water level if so desired at some future time.

10. Single spud, offset from the center.

11. Stacker, canvas covered.

12. Dredge to have 40 hp horizontal boiler, water pump and injector.

13. Quote shall be F.O.B. San Francisco or Seattle.

14. Quote constructed on ground, ready to operate.

15. How long after receiving order, could they make delivery?

While negotiations were beginning for purchasing a dredge, planning continued for building and equipping the camp at Coal Creek. Supplies for the new camp arrived by riverboat at Slaven's Roadhouse on the banks of the Yukon in June 1935. During the next several months, crews constructed a rough road from the roadhouse, eight miles upstream to the camp and a two-mile long ditch along the hillside bringing water to the mining area for stripping and thawing.

|

| Camp No. 1 near the confluence of Cheese Creek and Coal Creek (circa 1941-42). View is to the northwest with the machine shop and parts warehouse visible in the back-center of the photo. The Coal Creek dredge is visible in the distance at the right side of the photo. Frank Hall Collection, photograph courtesy of Frank Hall. |

The camp itself consisted of frame buildings, mounted on skids for moving them from one location to another as the dredging operation moved down the drainage. Even the mess hall consisted of two sections; each mounted on log skids eighteen inches in diameter. Initially, there were a series of four-man bunkhouses, a gold room for cleaning and assaying, an office, a machine shop, and a tractor repair shop.

Activities continued on several different fronts. First, the camp at Coal Creek had to be established, manned, outfitted and work begun on additional drilling to determine the exact boundaries of the placer. Second, bids for a dredge were received, evaluated, and a decision made on which manufacturer would provide the best product for their money. Most of this work took place in San Francisco and Vancouver, with input from Patty in Alaska as needed. McRae, true to his style, hired the best people possible for running his operations letting them do their jobs with very little input or oversight from him.

Five manufacturers submitted bids for a dredge:

| Yuba | $127,000.00 | FOB Seattle |

| Bucyrus | 110,000.00 | FOB Seattle |

| Peake | 88,950.00 | FOB San Francisco |

| Johnson | 86,975.00 | FOB San Francisco |

| Bethlehem | 78,225.00 | FOB San Francisco |

Of the five bids, Bethlehem proposed building a three cubic foot dredge contrary to the request and therefore dropped from consideration. The Yuba and Bucyrus presented their proposals verbally. These proposals were considerably above those of Peake and Johnson. In addition, these bids did not include specifications as to what type, size or style of dredge they offered at the proposed price. Consequently, these bids could not be subjected to a detailed comparison with the others. Janin stated that because of the markedly higher cost for these dredges, the companies were probably offering a heavier dredge than Gold Placers Incorporated requested. The Yuba and Bucyrus bids were thus dropped from consideration also.

Janin noted that:

A comparison of the specifications submitted by Peake Engineering Company and by the Walter W. Johnson Company was made in detail. Peake and Johnson were formerly partners and together developed the small dredge so successfully used in Alaskan and other fields. I think over thirty dredges being built by these parties. The design used by either would closely follow the other. Their FOB prices are very close. Peake figured on a 20 ft. digging depth, which would add about $2700.00 to the Johnson bid, but overlooked the heating plant and wrongly figured on electric motors for screen and stacker drive. The Johnson specifications covered some modern arrangements not covered in the Peake bid, based upon recent operating experience. Johnson also figured a larger hull than Peake. [25]

The Johnson Company submitted a proposed price for the dredge delivered, assembled and in operating condition, at Coal Creek. Janin states that it is "of decided advantage to have a bid from the dredge completed on the property by the [c]onstruction [c]ompany and given a trial run under their direction." Once the machine was up and running, with at least most of the "bugs" worked out, it would then be turned over to Gold Placers Inc. in "thorough operating condition." By taking this route, the company would have the advantage of knowing in advance, just what the completed dredge would cost them, within reasonable limits. Taking this tack eliminated delays caused by adjusting the new dredge. The Johnson Company was experienced in dredge construction and would be able to assemble the dredge in better time than the crew Gold Placers Inc. planned to hire. They also had the incentive of getting the job done quickly. [26]

It appears from Janin's notes that the Peake Company was unwilling to provide a price for the dredge, assembled on-site. His concern here is that the company's interests would end once the dredge parts and materials arrived at Coal Creek, although they were willing to provide an experienced engineer to assist with assembly.

A number of changes to the original specifications were submitted to the Johnson Company who then submitted a revised proposal showing these changes and adding an additional $1200.00 to the original bid. Janin notes that the changes resulted in a change in the hull design that cut $2700.00 from the cost, thus an overall savings of $1500.00. In the end, the cost of the Johnson Company dredge, built on-site at Coal Creek, would be $143,000.00.

In order to have a solid basis on which to compare the remaining bids, Janin enlisted the services of George Dyer, whom he calls "an experienced dredge constructor with considerable Alaskan experience." [27] McRae asked Dyer to estimate the cost, taking the initial Johnson bid of $86,975.00 for the dredge, and provide an approximate cost for the dredge, constructed on-site. His figures showed the following:

| Johnson bid FOB | $86,975.00 |

| Freight, estimated | 24,450.00 |

| Construction | 30,000.00 |

| Contingencies | 5,000.00 |

| Total | $146,425.00 |

Dyer provided the following figures for a crew to assemble the dredge, based on three months work. He commented that "if this work runs into the winter it will cost more for several reasons" but failed to elaborate on what these reasons were.

| Position/Title | Cost per Month |

Cost for 3 Months |

| Engineer manager | $1,000.00 | $3,000.00 |

| Assistant (will also be book keeper) | 150.00 | 450.00 |

| Diesel mechanic | 200.00 | 600.00 |

| Diesel mechanic helper | 150.00 | 450.00 |

| Head carpenter | 180.00 | 540.00 |

| Second carpenter (2 men @ $150.00 ea.) | 150.00 | 900.00 |

| Caterpillar man | 180.00 | 540.00 |

| Cook | 180.00 | 540.00 |

| Cook's helper | 60.00 | 180.00 |

| 20 laborers at $150.00 or $5.00/day | 9,000.00 | |

| Travel expenses for seven men | 1,400.00 | |

| Food for thirty men. 90 days at $1.50/day | 5,000.00 | |

| Total approximately | $22,500.00 | |

Dyer's figures included the cost of constructing the camp (including boardinghouse, cooks' quarters, office and manager's house, bunkhouses and bathhouse, storage facilities, tool room and shop). They also took into account tools, caterpillar tractor with a bulldozer, a self-dumping scraper and camp equipment making an approximate total of $35,000.00. The company could purchase additional supplies of hardware, tools and spare parts for the machinery as needed. Janin suggested the Northern Commercial Company, the great northern supplier, as the source for "ordinary supplies." [28]

Based on Dyer's figures, Janin determined that the Walter W. Johnson Company bid of $143,000.00 was the best they would find. As a final note, Janin states that, "It is possible to have the dredge completed on the property by the end of the present season (1935) if the order for the dredge is placed immediately, and no unforeseen delays occur, by strikes, etc. The cost of construction would be higher and there would be little advantage in having the dredge completed at the end of this season as compared to having it ready to start about the 10th or 15th of June next year."

The price for the dredge from the Johnson Company only included the cost of freighting the pieces from their shops in San Francisco, via Skagway and Whitehorse to the riverboat landing at Slaven's Roadhouse. It did not include the cost of getting the parts from the Yukon River to the assembly point. Janin notes that "hauling materials from the mouth of Coal Creek to the property is a serious [problem] during the summer months; according to Patty a road costing upwards of $45,000.00 would have to be built and proper hauling equipment purchased." [29]

Janin realized the savings that could be had by arranging to have the dredge parts delivered to the mouth of Coal Creek during the summer of 1935. Here, they could be stored until winter when the ground froze sufficiently to allow hauling them to the site at a greatly reduced price. In addition, this would put the parts at the right location for beginning construction as soon as weather conditions permitted, possibly as early as April 1st.

The Johnson Company agreed with Janin's proposal and claimed they could have the dredge in operating condition by early June. In order to meet this time schedule, a camp would have to be built during the summer of 1935, food supplies brought in that summer or fall and kept over the winter for the construction crew. To keep the food supplies from freezing, a suitable storehouse was required as well as living quarters for a watchman.

Janin continued with his recommendation of putting the camp buildings on skids thus facilitating moving them to new locations as the dredge traveled up and down the creek. He also recommended that it would be a good idea to have an experienced dredge operator visit the site during the summer of 1935. This would assist with siting the camp and dredge pit, as well as starting preparations for stripping and thawing the ground. This too, he claimed, would make for considerable savings in both time and expense.

Stressing the importance of obtaining the services of a good dredge operator, Janin recommended they consider George Dyer, the same man who provided the estimates for comparing the various bids, for the position. Janin stated that he felt Dyer "would be acceptable to the construction company (the Johnson Company), and would be an excellent man to have in charge of the property afterward." He continued reiterating that Dyer was "an experienced dredge constructor and operator, and was manager at the Fairbanks Gold Dredging property for two years. He is available at present for work of this character." [30] In the end, the Johnson Company provided their own foreman, Sam Palmer, to assemble the dredge.

McRae and Patty went to San Francisco and negotiated the final contract for the dredge with the Walter W. Johnson Company (See Appendix I). One of the more innovative differences between this dredge and others working in the North at the time was the metal "pontoon hull." This new design marked a radical departure from traditional dredge building. Previously, dredges were large wooden-hulled barges supporting the working superstructure and dredge machinery. These were more susceptible to the stresses and strains associated not only with digging, but also with the action of the ice during the winter that could literally crush a wooden hull. [31]

Once Gold Placers, Inc. let the contract to the Johnson Co., they again focused attention on the camp at Coal Creek. Johnson's company agreed to supply many of the heavy tools required to construct the dredge including a drill press, lathe and electric welding outfit. Once the dredge was completed and successfully through its two-week trial run, the Johnson Co. would make these tools available to Gold Placers Inc. at a reduced price of fifty percent of what they cost new — quite a bargain. Any large-scale mining operation required the services of a blacksmith for fabricating and repairing parts. Gold Placers Inc. had what Patty described as a shop with a "good large hearth forge, anvil, and an assortment of customary blacksmith tools -- also a fair assortment of iron of various dimensions." Patty also wrote that they had purchased an acetylene "presto welding outfit" that would be available for the Johnson crew, but cautioned that they should plan to ship the necessary tanks of oxygen and acetylene for using it. [32] In addition to building the infrastructure of the mining camp, they made preparations for the dredging operations expected to begin the following season.

The Coal Creek dredge was built in San Francisco then dismantled and crated for shipment to Alaska. Careful consideration was necessary however, because once the parts, almost four hundred tons of them, were shipped to Skagway they would then be loaded onto the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad for the trip to Whitehorse. The company had to measure each tunnel along the railway to ensure that the crates would clear. From Whitehorse, the parts were loaded onto a barge and pushed by a sternwheeler downstream to the mouth of Coal Creek. [33] Upon arriving at the landing at Slaven's Roadhouse, the crew realized that the riverboat did not have equipment sufficient to handle the weight of the cargo. The challenge of off-loading was monstrous, but as was the case in many Alaskan ventures, it was not insurmountable. [34]

|

| Unloading the dredge pontoons at Coal Creek. The man facing the camera (in the overalls) is Frank Slaven. His roadhouse is visible on the high bank at the upper right. Note the tripods that supported a telephone line which allowed the crew on the beach to communicate with the camp approximately 7 miles up Coal Creek. George Beck Collection, photograph courtesy of Max Beck. |

Once the parts were delivered to the mouth of Coal Creek, they were placed on the bench above the river where they would remain until October when the ground was sufficiently frozen to haul them to the construction site. The very large pieces were put on skids to prevent them from freezing to the ground. In order to facilitate construction the following spring, Patty requested a diagram from the Johnson Co. to allow him to "site" the parts around the dredge pond. [35]

STRIPPING AND THAWING OPERATIONS

The unique climatic and ecological conditions facing placer miners in Alaska requires them to carry out a complex stripping and thawing process before beginning actual dredging operations. At the new Coal Creek camp, cat skinners [36] used bulldozers to strip away the trees, brush and tundra that formed an insulating "blanket" over the surface. This exposed a shiny, black surface of frozen "muck" varying in depth between six and twenty-six feet. The gold bearing gravels lay below.

A series of hydraulic nozzles (called "giants") removed the muck by spraying high-pressure water brought from the hillside ditch. The water first thawed, then washed away much of the muck. Patty estimated that, each day, the summer sun was capable of melting approximately four inches of muck that was then swept away by the water. He further noted that during these operations Coal Creek below the stripping area ran black with the ancient sediments. Within a few weeks the frozen gravel began to show.

|

| Using a hydraulic giant to thaw and strip away the "muck" that covers the alluvial graver on Coal Creek. Everett Hamman Collection, University of Alaska-Fairbanks. |

This permanently frozen gravel (called "permafrost") was as resistant to working as reinforced concrete. During the first operating season (1935), Gold Placers Inc. relied upon steam thawing to prepare the ground for dredging. This involved driving steam points, sections of pipe with a chisel point connected to high-pressure steam hoses, into the permafrost. Steam escapes through the point, thawing the surrounding gravel. Over the winter of 1935-36, [37] the company contracted with several local woodcutters to cut and stockpile approximately 250 cords of wood needed to fire the 40 horsepower boiler they used during their first season. [38]

Thawing operations came under the jurisdiction of the dredge master, Fred Obermiller, based in part on his years of experience with operations at the Fairbanks Exploration Company. When the dredge started working the steam-thawed ground, initially Patty reported conditions as "nearly perfect." His optimism was short-lived when the dredge struck ground that had re-frozen over the winter. Patty noted in the company's first annual operating report that: "The steam thawed area embraced 18,000 cubic yards and cost 34 cents per yard . . . and proved worse than useless. This steam thawing, when successfully done, is very expensive and will not be attempted in future seasons." Because steam thawing proved to be such a failure, Patty turned to using cold water, drawn from Coal Creek, above the mining area, for thawing the frozen gravels. [39]

Cold water thawing is similar to using steam, except that, as the name implies, cold water is used. As soon as the stripping crews were finished and moved on to new areas, the thawing crews moved in with their lines of hydraulic hoses, pipes, and thawing points. Cold water points consist of a ten-foot length of heavy gauge pipe, seven-eighths of an inch in diameter, with a hardened chisel point welded to one end. The upper end had threads for connecting a hose or additional sections of pipe as the pointman drove it deeper and deeper into the gravel. Water, under pressure, flowed through the pipe where it slowly seeped into the gravel through two holes on either side of the point. As the ground slowly thawed, the points were driven deeper and deeper into the gravel continuing the thawing process. Patty estimated that water flowing into the pipes from the hillside ditch had a temperature of approximately 45 degrees. When it flowed out of the ground around the thawing points, it had cooled to roughly 35 degrees. Thus, the water transferred approximately 10 degrees of "heat" to the ground facilitating the thawing process, all at a minimal cost to the company.[40] By mid-July (1935), sufficient ground was thawed to allow dredging operations to begin with estimates that by the end of the summer, sufficient ground would be stripped for "one or two years ahead." [41]

In 1936, they started driving the first 250 cold water thawing points on May 18. Within two weeks, on June 1, all of them were on bedrock and, as Patty noted "doing good work." An additional 250 points were on hand. The flanged feeder pipe to supply them was due on the first down-river boat from Whitehorse on June 5th. Unfortunately, the White Pass and Yukon Route failed to load them on the first boat, although they made arrangements months in advance. Instead, the pipe was loaded on the steamer Klondike that sank, taking Gold Placers' supplies with it. The company placed a duplicate order that arrived in late July. In addition, they salvaged some of the original order from the wreck. [42] An additional order of points arrived in August, and a final order for 250 more points arrived late in the season that would go into service in 1937, giving the company nearly 1000 points for thawing.

Unlike steam thawing, water thawing proved so successful that throughout the 1936 season, with the exception of the steam thawed ground that re-froze, the dredge was never bothered by frost in water thawed gravel. This showed the method reliable and thorough as well. Its use at Coal Creek was the first in the Eagle-Circle mining districts.

The company kept careful records to enable confidently replicating their successes elsewhere. [43]

Occassionally, much to the amusement of the crew, General McRae would walk around the operation when visiting the camp. Several times while crossing the thawing fields, the surface appeared solid, when in fact it generally had a frozen "crust" over the thawed gravel below. More than once McRae's weight caused the gravel to give way sending him waste deep into the cold water below. Reports have it that the General always took it in stride and made a joke of it, although it must have been an extremely cold joke. [44]

Because of the problems associated with getting the points and feeder pipe delivered, there was not sufficient ground thawed ahead of the dredge to operate for the entire season. Because of this, the dredge shut down on October 5, 1936, a full month ahead of schedule. [45]

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO "FEED" A DREDGE?

One of the points that could easily be overlooked, or at least miscalculated is how much fuel would be needed to operate the dredge once it was assembled. Again, owing to the good planning on the part of Gold Placers Inc., this question was posed to the Walter W. Johnson Co. who supplied the following advice: "The dredge would be powered by two Atlas engines, one to power the digging ladder, winches, screen, etc. and the other to power the pumps." These engines combined used approximately 180 gallons of fuel each day. The company engineer, A.P. Van Deinse, recommended, with an estimated startup date of June 10, 1936, that a fifty-day supply of fuel would amount to about 9,000 gallons. An additional 1,000 gallons would be needed for the various tractors. He figured that the 10,000-gallon supply would be sufficient to get the company through early August. This would give them the opportunity to have fuel shipped via barge from Dawson for the end of the season and the beginning of the next, until the Yukon was again open to navigation. In addition to the diesel fuel to power the engines, Van Deinse restimated that the Atlas engines would each use approximately one barrel of lubricating oil per month. He recommended that they order seven barrels to cover both engines and the tractors. [46]

He addressed the company's needs for fuel and oil as requiring a "liberal supply of diesel fuel and engine oil . . . and a large number of container[s] or drums for this material bought unless arrangements can be made with the oil company for rental of drums or purchase of material in non-returnable drums. These latter cost about $1.50 each as compared to $8.00 or more for the heavier drum." [47]

One element that made building a new dredge in Alaska something different from that in the California gold fields was the short navigation season on the Yukon. Throughout the correspondence between Gold Placers Inc. and the Walter W. Johnson Company, the need to have the parts for the dredge shipped before the last boat left Dawson was imperative. On July 6, 1935, the issue began to take on serious overtones when Joralemon wrote to Janin expressing his concerns:

Are [Walter W.] Johnson and [A.P.] Van Deinse trying to get out of a winter trip to the Yukon and of winter construction? It certainly seems so, from the fact that the pontoons, which must be there at the start of construction, are the last things on the shipping schedule and are not even fully designed yet. Unless they make this year's last boat, the darned dredge won't be running until September of next year — and Johnson will make a lot of money by building it in the nice summer weather. It was a big mistake to have the penalty so small. [48]

The General (McRae) suggests that we see both Johnson and Van Deinse together before I go North. I'll be in the office all day Thursday, the 11th, and can see them any time you make the appointment. Meanwhile let's think of all the arguments we can think of to make them come through. Doesn't the contract make it possible for us to insist on having their crew at the property in March whether the pontoons, etc. arrive or not? [49]

It is unclear what brought on Joralemon's sudden concern over the shipping dates. On August 9, Van Deinse wrote to Patty informing him that "all material for the dredge will have left San Francisco" with the exception of sixty percent of the superstructure. The company had difficulty in receiving the raw materials from eastern manufacturers but expected it to arrive the following day (August 10). With an anticipated 12 days needed to fabricate the parts, they would ship them as soon as possible. [50] Apparently, there were a number of concerns on the part of Gold Placers Inc. over shipping various parts as illustrated in several pieces of correspondence between McRae, Joralemon and Janin in late August. In the end, they postponed the contracted startup date by two weeks, until June 15, 1936. McRae wrote to Janin that he appreciated his "desire not to disturb the contract with Johnson until everything was in transit." He notes further that the shipments should be "followed up so there would be no unnecessary delay at transfer points — Seattle and Skagway. It is quite a relief to me to know that this shipment is all in transit." [51]

By the time the last steamer had gone downriver for the season, Patty notified the Walter W. Johnson Co. that all the parts "at least those that can be identified as belonging to the Coal Creek Dredge, have arrived at Coal Creek." He pointed out that it is "impossible to make an absolute check on account of the way much of this equipment is billed; for example, a way bill may read '1 bundle of mining machinery' or '1 sling of mining machinery' without referring to specific items." [52]

Patty further pointed out that: "Some of these bundles [were] broken in transit and the White Pass people have had considerable trouble in sorting out these broken bundles to know just what belongs to the Coal Creek dredge. For future shipments it would be a good plan — and a great help — if some distinctive stripe were painted on each crate and on each piece of pipe or casting." In referring to the actions of the White Pass personnel, Patty commented that: "The White Pass people have been duly impressed with the importance of getting all of the material on the ground this fall and they have co-operated with us very well. On the last shipment, they adopted the policy of leaving any doubtful equipment at Coal Creek. So we may find in the spring that we have some orders there that belong elsewhere." [53]

By December 1935, the operation at Coal Creek was well underway and heralded in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner under the headline: "NEW MINING CO. STARTS BIG WORKS." Among the innovative developments at the new camp was manner of constructing the ditch to bring water from the headwaters of Coal Creek to the dredging area. In this case, the News-Miner reported that this was the first time a tractor and bulldozer constructed a ditch, resulting in "very low costs." In addition, the U.S. Signal Corps installed a radio station that provided weather reports twice daily and proved valuable for emergency communications. [54]

The Alaska Road Commission entered a cooperative agreement with Gold Placers Inc. for seven miles of right-of-way for a permanent road from the landing at Slaven's Roadhouse up to the new camp. The camp crews undertook a good deal of the work during the summer and would continue working the following year.

Among the individuals employed at Coal Creek camp were: Fred Obermiller of Fairbanks, formerly with the Fairbanks Exploration Company, serving as dredgemaster; Charles Murray was the general foreman for the project; Phil Berail as hydraulic foreman; Eugene Moore was in charge of the engineering work. In Woodchopper Creek, Charles Herbert was engineer-in-charge of the prospecting work with Tom Radovich as shaft foreman. [55]

|

| Hauling dredge parts from the Yukon River to Camp No. 1 where the dredge was assembled. Beck is driving the tractor pulling the spud. The sled on which the spud is lying is currently located near the Coal Creek airstrip. George Beck Collection, photograph courtesy of Max Beck. |

CONSTRUCTING THE COAL CREEK

DREDGE

Hauling the dredge parts and equipment 6-1/2 miles upstream to the dredge pond began on March 6, 1936 and was completed within two weeks. Two tractors, each pulling two sleds, moved approximately 350 tons of materials. Construction began on April 8 and was completed on June 18, 1936 "except for some missing equipment, which failed to arrive on the first down-river boat." [56]

Many people living along the Yukon River during the 1930s sought out whatever jobs they could find to help bring in a little cash. W.E. "Bill" Lemm [57] had come to the country in the early 1930s at his brother's request. After he arrived, they built a cabin on the Tatonduk River [58] above Heine Miller's camp. While living there, he and his brother spent their first winter (1934-35) cutting cordwood, on a contract to Miller, for steamboats plying the Yukon. The next summer, they moved into Eagle where they gardened and worked for the Alaska Road Commission.

|

| Metal are assembled forming the pontoon hull are assembled on the frozen surface of the construction pond at Camp No. 1. NPS photo, Bill Lemm Collection. |

During the late winter-early spring of 1936, Lemm heard about the operations at Coal Creek and decided to apply for a job. He walked from Eagle to Coal Creek, covering a distance of approximately 110 miles in only 3 days! When he arrived, he found a number of men "batching it" [59] at Slaven's Roadhouse and decided to throw his lot in with them. Each of the men had assigned chores including cooking, cutting firewood, hauling water, etc. According to Lemm, you quickly learned that if the food was not particularly to your liking, you kept your comments to yourself or you pointed out that it in fact was "just the way I like it." Or the next day you would be the cook.

From Slaven's, Lemm walked up to the new camp and talked with the camp foreman about a possible job. The only thing available at that time was cutting wood. Lemm had a good bit of experience with this and jumped right into it. After that, he spoke with Sam Palmer, the Walter W. Johnson Co. engineer in charge of construction. Palmer in turn sent him to the cook to see if there was room in the camp for him. Seizing the opportunity, Lemm went to the cook and informed him that he would be there for dinner. The cook, Frank Estrada, "Well we've already got enough in here now," to which Lemm responded that "There's always room for one more." Consequently, Lemm talked himself into a job. [60]

When Lemm arrived at the camp, work on the dredge was just beginning. The crew dug and filled the dredge pond the previous year. The ice provided a flat surface for constructing the dredge. [61] First, they positioned and bolted together the pontoons. After accomplishing this, the superstructure began to take shape.

Lemm was assigned to what he called the "bull gang" working with the steel superstructure. Although he freely admitted that he had no experience with steel, he was apparently a quick learner. When he set a five-foot long crow bar on top of a steel cross member, another crewman, a "big burly fellow of a guy" also named "Bill," saw it and quickly pointed out that "I don't want you EVER to put a bar up like that. If another piece of steel hits that and deflects it, it could go right through a man!" Several days later another worker laid a bar in a similar manner and Lemm received the blame for it. When "Big Bill" came over to Lemm yelling "I told you not to put that bar up there and I have a damn good notion to fire you!" Lemm responded, "Don't jump all over me. I didn't do that. When you told me not to, I won't!" After that, "Big Bill" backed off and never said a word. [62]

Apparently, this confrontation with Lemm standing up for himself raised "Big Bill's" confidence level in him tremendously. Later, when other members of the crew provided their input into how to do something, "Big Bill" would quickly point out "What the hell do you know about it? I'm the boss of this job!" Then, he'd go over to Lemm asking for his opinion and if it was sound, generally responded "That's a hell of a good idea. Let's do it" [63]

Assembling the dredge superstructure was similar to building a modern steel-framed building. Each pre-fabricated piece had the appropriate holes drilled for assembling it machined into it in San Francisco. As they lifted each piece into place, one worker aligned his end using a "spud wrench." [64] The first person to get their wrench in had the easier time. The second generally had to do a lot of leveraging and wrestling to align his end. On one occasion, Lemm consistently beat his partner, Ray, to the punch. Because of this, Ray had to work more than Lemm and he took it quite personally. After the dredge was completed, the crew got some time off to go to Fairbanks. After a night of heavy drinking, something that the crew tended to do every time they went to town, Ray drunkenly informed Lemm "I'm gonna clean your clock for ya!" Lemm was always one for getting out of tight situations using just his wits. He told Ray "... that's all right if you want to do that, but can't you wait until tomorrow when we're both sober?" Apparently, after sleeping it off, the issue never came up again. [65]

Working on assembling the dredge was not without its share of danger. In one instance, a crewman pulled a long wooden 2x8 from between two cross members. The weight of the opposite end, once it cleared the first beam, caused it to drop rapidly pulling the end out his grasp. It fell to the deck, striking another worker squarely on the head. As it turned out, the man it hit was one of the engineers on the job. According to Lemm, "he sagged and went down and pretty soon we got him to and he was all right. It didn't hurt him but outside of that he had a little bit of a headache." In this case, he was lucky. The blow could very well have killed him.

|

| Superstructure beginning to take shape on the Coal Creek dredge. George Beck Collection, photograph courtesy of Max Beck. |

In another incident involving objects falling, Lemm was working on the deck when a compressed air can fell down, narrowly missing him. Next, a file came crashing to the deck. Finally, a wrench came down from above. That was as much as he was going to tolerate. Climbing into the girders, he informed the bumbling worker to "Get the heck out of there and get someplace else if you're going to drop the damn tools and things." [66]

The heavy machinery and parts of the dredge required heavy equipment to move them about. Caterpillar tractors were used to haul parts from place to place, blocks and tackle were used to hoist pieces into place, and occasionally extra-ordinary means were required to accomplish the tasks at hand. One day, it was necessary to remove the big main drive gear, called the "bull gear." [67] This gear supplies the force operating the entire dredge, including turning the bucket chain and screen. The gear fits on a shaft. A key and keyway in both the shaft and gear hold it in place. Once put in place, it is virtually impossible to get apart, unless you use a little "applied force."

In order to drive the key back out, the foreman used a quarter of a stick of dynamite, placed behind the key with mud packed around it. After informing the others, "I'm going to light this and I want everybody to watch this thing (the key) so we don't lose it. It's the only one we've got." After the explosion, one crewman simply walked over and picked up the key. The charge was not sufficient to damage the gear, just enough to force the key out, breaking the gear loose.

Fortunately, in 1992, Bill Lemm accompanied Yukon-Charley Superintendent Don Chase on a trip down the Yukon during which Lemm reminisced about much of his life on the river and at Coal Creek. In a letter sent to Chase after the trip, Lemm provided the following list of individuals who worked at Coal Creek, along with their jobs around the camp: [68]

| Chuck Herbert [69] | Surveyor and engineer |

| Fred Obermiller | Dredge master and overall foreman |

| Pearl Nolan | Winchman |

| James McDonald | Cat driver and winchman |

| Bruce Thomas | Point boss |

| Phil Berail | Hydraulic boss |

| Bert Kellogg | Machinist |

| Jack Ellis | Cat skinner |

| Harold Hall | Ditch walker |

| Glen Franklin | Bookkeeper and timekeeper |

| Bill Lemm | "Cat driver, freight hauler and it seems I got myself into doing many things such as cutting wood with a buzz saw attached with [a] power unit on [a] cat, helped pour gold bricks if I was handy, even to build [the] portable cookhouse for the drill crew for the Charlie (sic) River test crew." |

Life at Coal Creek camp had its humorous side as well. Fred Obermiller, the dredgemaster, lived in Fairbanks. His wife was expecting a baby while he was at camp. When she had it, Fred got word via the radio the US Signal Corp. installed at the camp. Later a plane flew over dropping a box of cigars with a small parachute attached. Cigars were not the only things falling out of the sky before making the airstrip. The postal service handled mail delivery to the creek the same way. The plane from Fairbanks would fly over; bank down low and as it passed overhead and the mailbags fell to the ground. One day, one of the bags landed somewhere and to this day has not been found.

One time when the camp ran out of fresh meat, they radioed Fairbanks requesting that a quarter of frozen beef be flown out. Making a pass down the Yukon River, the plane banked onto its side. The beef simply slid out the open door free-falling to the gravel bar below. Because it was frozen, the fall and subsequent landing had little effect on the meat, except that it would occasionally break a leg bone. However, Lemm noted that, "Boy it would bounce like a football. Then we would go pick it up. There'd be a few rocks in it because it bounced pretty good, but that didn't hurt anything." [70]

|

| Charley River drill crew. The only two men identified in this photo are Chuck Herbert and Leonard Stampe. Unfortunately which ones they are was not recorded. NPS Photo, Bill Lemm Collection. |

While getting the camp at Coal Creek up and running, Patty continued to examine other drainages in the vicinity for possibly expanding their operation. For years, the USGS had been noting the potential for gold production on Woodchopper Creek, immediately west of Coal Creek. In Patty's estimate, the company could realize a considerable profit, with somewhat reduced startup costs because of the proximity of the two creeks by operating from a central location. The night after the first cleanup at Coal Creek, Patty, feeling both optimistic and confident with their initial results, decided to suggest branching over to Woodchopper to McRae. Typical for his management style, McRae slapped Patty on the back and said, "When you're winning, always crowd your luck." [71]

Consequently, McRae, Patty and the other directors of Gold Placers Inc. formed a second company, Alluvial Golds Inc. operating on Woodchopper Creek. Although run as two separate entities, both had the same management structure and most of the same personnel. Ira B. Joralemon conducted extensive reviews of the mining records for the Woodchopper Creek properties coming up with an initial report showing that the drainage had a potential of 2,690,000 cubic yards of mineable gravel, averaging $0.74 per cubic yard. Once again however, Joralemon thought the best way to recover the gold would be by using draglines rather than a dredge. However, he did note in his report that if it were possible to buy a "second hand dredge that will dig to 30 feet very cheaply within the next year, it may be better to eliminate the drag line." [72]

Joralemon estimated that it would take an initial capital outlay of $140,700 to acquire options on the Woodchopper Creek claims and get Alluvial Golds Inc. up and running. Patty began looking around the Interior for a used dredge and located one on Fish Creek, near Mastodon Dome (one of the old Berry Brothers dredges). Upon evaluating its condition, it proved to be a "pretty unwieldy plant" but according to McRae, it "might be interesting for Woodchopper Creek if the price is right." It appears that either the price was not right or moving the dredge would prove to be a much greater task than expected. They dropped the dredge from consideration almost as fast as Patty found it. [73]

POSTAL SERVICE ON THE CREEKS

Throughout history of the Yukon River, the United States Postal Service has provided more to the miners in Alaska then simply a means of getting an occasional letter from back home. It also served as a conduit for supplies from such companies as Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck & Company. In addition, miners used the postal service to ship their gold. Each shipment being insured up to $1,000.00. [74]

The post office at Woodchopper Creek opened on April 30, 1919 with Fred Brentlinger as postmaster. Due to a decline in the needs of the area miners, it was discontinued on October 15, 1923 and moved to Circle. [75] Following the resurgence in mining activity in the early 1930s, the Postal Service appointed Mrs. Kate Welch, wife of the owner of the Woodchopper Roadhouse (Jack Welch), postmaster on February 24, 1932. She assumed the position in mid-August holding it until the end of August 1936 when the post office moved to Coal Creek and became associated with the mining camp directly. [76]

The crew constructed a building specifically to house the combination Coal Creek Post Office and radio station. Clyde A. Cobb served as the original postmaster. Although appointed on the postmaster position on April 15, 1936, he did not assume the responsibilities until the following August. Glen D. Franklin, who took over the responsibilities in May of 1938. replaced him. Franklin worked for Gold Placers Inc. as the company accountant at the time. [77] Phil Berail, who worked as the hydraulic foreman at Coal Creek under Gold Placers Inc., and who had previously been a miner and trapper from the upper Charley River area, was named postmaster in February of 1943. He served, at least on paper, for the next two months. There are no records of who succeeded Berail until May 31, 1945 when the office again closed and moved to Circle.

Following World War II, the government re-established the post office at Coal Creek on May 16, 1946. Mrs. Sarah A. (Sally) Murray, wife of the Gold Placers and Alluvial Golds accountant (Ted Murray) was appointed postmaster. During the time Mrs. Murray served, the post office would move back and forth between Coal Creek and Woodchopper depending on which camp was serving the dredge operations each year. She held the position until July 22, 1961 when the office was transferred to Fairbanks and the Coal Creek post office ceased to exist altogether. This coincides with the time when operations on both creeks ceased and the dredges shut down. [78]

DREDGE OPERATIONS AT COAL CREEK

Under the terms of the contract, the Walter W. Johnson Co. would provide a trial run of at least two weeks. During this time the various "bugs" would be found and worked out before turning the dredge over to Gold Placers Inc. On July 1, 1936, as Ernest Patty describes it:

Finally, we were ready to go into production. The construction pond itself was flooded to float the dredge. Its two diesel engines began coughing; the winchman moved the dredge out of the construction pit and the bucket line started to revolve and bite into the gravel.

It was a great moment to hear the thump of the first gravel falling into the hopper. As it cascaded from the hopper into the big revolving screen, I could see the finer gravel, which would be sand and gold, dropping through the slots in the screen and onto the gold-saving sluices.

Although viewed with great anticipation, the initial start-up led to discovery of a series of problems resulting in essentially the first two weeks being a "total loss." [79]

Patty blamed this on the fact that ground thawed during the 1935 season partially refroze, as discussed earlier. In addition, Sam Palmer, while being a competent engineer when working at the Walter W. Johnson company headquarters in San Francisco, apparently was not up to the task of supervising on-site construction by himself. He went strictly "by the book," which in turn required making numerous adjustments and alterations to the machinery. [80]

Perhaps the most serious problem involved the uneven way the dredge floated in its pond. The original specifications called for a minimum freeboard (the distance from the deck to waterline) of two feet. When the dredge was first floated, in its working configuration with the spud down, bucket chain loaded, resting just off the bottom, Patty was shocked to see that the freeboard varied from 8-1/2 inches at the starboard bow (right-front) to 28 inches at the starboard stern (right-rear). The port (left) side ranged from 10-1/2 inches at the bow to 25-1/2 at the stern. Because of this, they added almost thirty tons of ballast (dead weight) to the stern of the boat leveling it out. [81] In a letter to Janin on July 29, McRae said the "Dredge looks more like a ship now." [82]

This problem perplexed the operators for quite some time as they adjusted and re-adjusted the ballast between the pontoons. It also infuriated company management leading to a number of terse letters and telegrams sent back and forth between Coal Creek, Fairbanks, Vancouver and San Francisco. In order for the dredge to work properly, it was necessary that it float nearly level to obtain the correct flow over the sluices and gold saving tables. If the bow sat too low, there would not be enough water flowing over the sluices to carry the gravel and lighter materials off. If the stern were too low, the water would wash all but the largest pieces of gold off with the waste material.

In addition to the potential loss of gold through the sluices, the costs associated with taking the ballast off the boat at the end of each season, replacing it the following spring, meant losing additional profits. For safety purposes, the company planned to remove the bucket ladder and drain the pond each fall allowing the dredge to sit on solid bedrock. In order to accomplish this, it would be necessary to remove all 30 tons of ballast each fall, replacing it again in the spring. If this was not done, when the pond was filled, the lack of counter-weight provided by the bucket ladder (which would not be loaded at the time, thus reducing the weight on the bow even further) would allow the bow to float faster and higher than the stern possibly leading to the dredge swamping at the stern.

In addition to the ballast problem Patty noted several other minor problems making requests to ensure the Walter W. Johnson Co. did not repeat them in designing and equipping the Woodchopper dredge. Among these were supplying a sufficient number of spring, or lock, washers. Dredges, by their nature, vibrate tremendously when operating under load. According to McRae, it was necessary for the crew to go throughout the boat, re-tightening nuts and bolts after operating only two weeks. The original order included what the company believed to have been an ample supply of extra nuts, bolts and miscellaneous hardware for the dredge after it was in operation. Because of the number of missing pieces during construction, the crew was required to use most of its inventory leaving few parts for repairs. Finally, according to McRae, wood supplied for the dredge was not seasoned properly. This resulted in warping and splitting. [83]

One of the more confounding problems encountered with the Coal Creek dredge was insufficient water flow in the screen to wash the mud, sand and gold from the gravel as it moved down the machinery. [84] They considered several options, among them, adding additional nozzles on both ends of the screen, possibly including more down the center. The company sent numerous letters back and forth between Coal Creek and San Francisco posing questions, possible solutions, and making recommendations for modifications to the plans for the Woodchopper dredge. The problem seemed to continue regardless of how much they increased the speed of the pumps. In addition, when the pump speed was increased, the engine driving the pumps began vibrating badly. In general, it just plain did not work as it should.

|

| Atlas diesel engines under construction on tne main deck. The engine to the left ran the pumps while the engine in the background ran the bucket line, screen, winches and stacker. George Beck Collection, photograph courtesy of Max Beck. |

Finally, after several months of trial and error, Patty ordered the diesel mechanic to disassemble the engine to see if there was some internal problem hindering its performance. Upon inspecting the intake manifold, the mechanic found a variety of desiccated meat, bones and other pieces of debris blocking the airflow. Thus, the engine simply could not breathe.

In trying to determine the source of the blockage, Patty noted in the letter accompanying the material to the Walter W. Johnson Co., that they were too large to have been dragged into the manifold by a rat. They appeared to be part of someone's lunch. There was no chance of sabotage at Coal Creek because the crew installed the engines as received. Most likely, someone dropped them into the engine during assembly at the Atlas plant. [85]

After reassembling the engine, the pumps worked as originally anticipated. The water flow through the screen was sufficient to provide good washing. Materials moved through the dredge without additional modifications. [86]

Between the problem with ballast and the pumps, it appears that a rift was developing between the partners in the Coal Creek enterprise. Patty, on-site at Coal Creek was frustrated with the many problems he was encountering. Joralemon, who had very little experience with dredges before entering the venture with McRae, expounded on each problem he received from Patty, forwarding his rendition on to Janin. McRae for the most part simply stayed in the background and let his managers deal with the problems as they arose. Finally, in a tersely written letter to Joralemon, Janin suggests that they get together in San Francisco, in an "executive session" with Walter W. Johnson himself. He stated that Johnson had incorporated most of the changes Gold Placers Inc. had requested for the Woodchopper Creek dredge. From that point on, he proceeded to lambaste the problems about which Patty complained.

First, he stated that, "It seems to me that the dredge master knows not too much and because he was once a winchman on an F.E. dredge thinks the little Coal Creek dredge should have all the doodads the former had. As one cost $460,000 for the 6 ft. and over $600,000 for the nine, it is hardly fair to expect a little $143,000 dredge to have the same."

He continued, "Another thing: -- if the [diesel] man Van [Deinse] had selected for the work gone on and been engaged by the Company (Gold Placers Inc.), there would have been no hasty conclusions re the engines and pumps. How meat and bones got into the manifold is beyond me, prehaps (sic), sabotage at the plant, I should have thought it would have a smell — perhaps someone was killed and ground up into sausage, there are still missing persons being hunted for down here?"

Finally, in addressing the ballast question, he pointed out that the big Yuba dredges required 145 tons. He personally put over 100 tons on a Lena dredge. In his opinion, thirty tons on a small four-foot dredge like Coal Creek was not out of the ordinary. The only thing Janin could fault the manufacturer for was not sending either Johnson himself or Van Deinse, his chief engineer to visit the dredge when it was almost completed for a final check. This would have "provided not only an expert who really knew the business but of some one in authority, to make immediate adjustments necessary on the ground." It is interesting to note that Janin summed up the letter with "I wouldn't show this to Patty, but it is OK to let the General see it." [87]

As previously mentioned, Joralemon's experience with dredging was limited, primarily to operations in the California gold fields. At Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, unlike California, the gold tended to be in large chunks or nuggets. In observing the action of the pebbles flowing over the riffles on the gold saving tables, he noticed that they moved too rapidly for the gold to settle sufficiently to be caught by the mercury in the sluices. To test his theory, he had one of the mechanics make an "artificial nugget," one-half inch in diameter from heavy solder. He attached a thread to the "nugget" so he could watch its progress through the riffles. When dropped onto the table, the water easily carried it down and out the tail sluice.

To remedy this problem, he devised a "nugget trap" consisting of nothing more than pieces of 1x4 cut long enough to fit across the table. When installed, this caused the water flow to hesitate just enough to allow the larger nuggets to fall to the bottom while the waste material flowed over the top of the dam. In order to test the trap, they installed it on only one table. The first day, Joralemon's "nugget trap" succeeded in recovering $50 worth of gold that otherwise would have been lost. Based on this experiment, the crew immediately made "nugget traps" for the other seven tables. Although results varied from table to table, the traps accounted for a considerable part of the total gold recovered. In summing up his modifications, Joralemon called it the "[greatest] return from an investment of a few cents for the 1x4s." [88]

During the 1936 season, a second penstock was constructed further upstream from the original one. Beginning the next season (1937), water diverted by the upper penstock would be used for stripping operations, water from the lower penstock would be used for the thawing operations.

After running continuously for just over two weeks, they shut the dredge down and the crew started pulling the riffles out of the gold saving tables. Patty described the crew's demeanor as:

Nobody said a word. We were all too keyed up. I had not felt the same stomach-gripping tension since my college days when I used to wait for a report on final examinations. [89]

The first cleanup was a rather joyous event at Coal Creek. General McRae, accompanied by his daughter, came to the camp for the occasion. Although in the end, Patty called the first seventeen days of operation a "total loss." When put into perspective, the dredge was new, the crew new and there remained many "bugs" to work out. Patty rationalized that "about two-thirds of this [poor performance] can be charged to the failure of the steam thawing and one-third on account of adjustments and alterations on the dredge." [90] The initial cleanup would be the decisive test of their investment. As Patty described it, "It would show whether we had the wrong pig by the tail." [91]

After collecting the amalgam from the sluices, they took it to the gold room in the assay office. There it was heated in a process called "retorting." At this point, the heat evaporates and drives off the mercury, leaving behind the gold "sponge." The mercury was recovered, by distilling the vapor, for continued use in the sluices. The assayer then melted the gold sponge in a furnace where the impurities floated ("slagged") to the top and the molten gold was cast into bars.

During the first several weeks, the dredge dug 30,300 cubic yards of gravel producing 597.420 ounces of gold bullion having a value of $18,578.24, an average of $0.62 per cubic yard. For the remainder of the season, the dredge processed an additional 165,000 cubic yards of gravel recovering a total of 3,896.74 ounces of gold valued at $122,092.29. [92]

Subsequent cleanups illustrate an increase in value to a high of 74.2¢ per cubic yard, followed by a steady decline down to 38.5¢ per yard which was considerably less than the first cleanup. As the operation continued, additional cleanups reflected the company's prospecting estimates almost exactly. Patty noted in his annual report that: "It is significant to note that the first three cleanups checked the prospecting exactly. This is exceptional for it is the experience of dredging companies that it generally requires three seasons of dredging for the law of averages to work out." [93]

Overall, the year's production proved successful with 204,800 cubic yards of material passing through the dredge. The dredge recovered almost 3,500 fine ounces of gold with a value of over $121,000.00. Since dredges are "cleaned up" every few weeks rather than daily, it is impossible to know just what the daily production figures may have been for the dredge. The first cleanup took place on July 29, 1936 after operating for 29 days. If Patty's comments about the first seventeen days are in fact accurate, the dredge was VERY successful during the final twelve days. Over the next three years, the dredge averaged slightly more than $23,000.00 per cleanup. The final two cleanups in 1938 skew the average considerably because the dredge worked unusually rich ground during October of that year. [94]

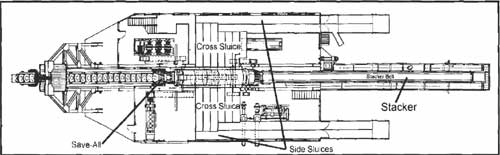

There were a number of design changes made during the first season. Among these: (1) extending the 'save-all' sluice to catch a greater amount of the spillage coming from the buckets; (2) replacing the upper section of the screen with one having larger openings to ensure more material was passing over the gold saving tables (sluices); (3) installing a "retarding ring" at the lower end of the screen to slow down the material passing through the screen allowing it to be washed more thoroughly; (4) installing a small grizzly and an additional sluice between the end of the screen and the stacker belt; (5) installing permanent nugget traps based on the temporary ones devised by Joralemon; (6) adjusting the riffles on the gold saving tables (sluices) and adding some larger riffles to slow the progress of materials as they washed down — similar to the nugget traps at the top; and finally (7) lengthening the stacker so material was carried farther astern before being dumped into the dredge pond. All of these improvements would be in place before the 1937 season and requests made in the specifications for the new dredge at Woodchopper Creek. [95]

As a dredge processes gravel, the gold accumulates in different sluices at different rates as illustrated in the following table, based on the 1936 production figures for the Coal Creek dredge. In this case, the sluices located directly below the screen captured over ninety percent of the gold immediately after falling onto them. The remaining ten percent settled out as the material continued down the cross and side sluices before passing out of the dredge with the finer tailings. [96]

| Sluice Location | Total Ounces of Amalgam [97 Recovered |

Percent of Total [98] |

| Upper Screen Sluice [99] | 3,471.10 | 66.4 |

| Lower Screen Sluice | 1,249.50 | 23.9 |

| Cross Sluices | 220.27 | 4.2 |

| Side Sluices (long) | 26.95 | 0.5 |

| Nugget Sluice [100] | 185.06 | 3.5 |

| 'Save-All' | 77.97 | 1.5 |

| Total | 5230.95 | 100.0 |

|

| Figure 2: Location of the various sluices on the Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek Dredges |

Perhaps one of the highlights of the year's operation was the fact that after properly adjusting everything and remedying the problems with frozen ground the dredge exceeded its guaranteed average digging rate of 2400 cubic yards per day by one hundred yards. This attested to the quality of the product produced by the Walter W. Johnson Company. On the down-side however, Patty noted that it fell short of the estimated 3000 cubic yard capacity Johnson predicted the dredge was capable of digging. [101]

COAL CREEK ROAD CONSTRUCTION

The placer area at Coal Creek extends from the Yukon River, approximately seven miles upstream. Gold Placers Inc. located its camp near the upper end of the placer so their facilities would be near where the dredge was operating. As the dredge moved up and down the creek, the crew moved the camp buildings from time to time as well. Constructing them on skids helped accommodate this.

The camp itself was first located approximately seven miles from the Yukon River. From the beginning, the logistics of getting equipment, supplies and men from the river to the camp caused problems because of a lack of a quality road. They hauled the parts for constructing the dredge overland after the ground froze and had a covering of snow.

During the 1936 season, Gold Placers Inc. constructed one and a half miles of "automobile truck" road from the camp, working downstream toward the Yukon River. The Alaska Road Commission (ARC) surveyed a right-of-way for the remainder of the road and a cooperative agreement was entered into between the company and the ARC to complete the road. Under the terms of the agreement, the ARC supplied a crew of men paying their wages and transportation. It also furnished a dump truck for moving road-building materials. Gold Placers Inc. supplied "subsistence" for the camp and a tractor with a bulldozer and a driver. [102]

The ARC crew arrived on June 14, 1936 and worked through the middle of October. The first two miles of the right-of-way, from the Yukon River, crosses frozen muck with numerous ice lenses. [103] After stripping the muck the ice began to thaw creating many problems associated with the deep mud. The only way to maintain a road over this portion was to corduroy [104] the entire stretch, covering it with a layer of crushed rock. [105]

The six and one half mile long Coal Creek road was completed to within one half mile of the Yukon River during the 1936 season. The ARC agreed to have its surfacing crew return the following year to complete the work and make any necessary improvements. Patty reported the cost of constructing the road as slightly less than $3500.00 for the season. [106]

The next season (1937), the ARC provided a crew and dump truck under the same agreement as the previous year. They completed the remaining one half mile of road to the Yukon River. Gold Placers Inc. constructed a bridge over Coal Creek and made minor repairs to the remainder of the road.

It was evident that without major changes, the two miles of road leading to the Yukon River would become unusable. The ice and soil conditions could not stand up to the heavy truck traffic. Even heavy corduroying soon deteriorated. Patty stated that the only way to bring this up to useable standards would be to have a heavy surfacing of gravel or "slide rock." The company again put in a request for the ARC to supply a crew and truck to work on the road in order to put it in "permanent shape." During 1937, the company spent $1500 on the road, bringing the total over the three years (1935-37) to $5703.47. [107]

By the end of the 1939 season, with the continued assistance from the ARC, Gold Placers Inc. constructed and surfaced seventeen miles of road from the landing at Slaven's Roadhouse up Coal Creek crossing the ridge to Woodchopper Creek. According to Patty, the road was in constant use throughout the summer. Most of the camp supplies and materials were hauled by truck. This virtually eliminated the need to haul anything by tractor further cutting transportation costs. However, the lower two miles of road required expending almost ninety percent of the total labor allocated for road construction during the entire season. Even at that, he calculated that it would be yet another season of work before this section became permanent. Overall, in 1938, they company spent $2761.26 on road construction and repairs. [108]