|

YUKON-CHARLEY RIVERS

The World Turned Upside Down: A History of Mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, Alaska |

|

CHAPTER EIGHT:

A NEW GENERATION TAKES CHARGE

The choice to appoint Dale Patty as resident superintendent was an excellent one. Summer at the mines had always been a family affair for the Pattys. Beginning in 1935, each summer when the boys finished the school year in Fairbanks, Ernest Patty, accompanied by his wife Kathryn and their three sons, Ernest Jr., Stanton and Dale spent their summers at Coal Creek. This continued for six summer. Suspecting that Alaska was vulnerable to attack by the Japanese before World War II, Ernest Patty moved his family to Seattle in 1940 where he felt they would be more secure. In 1945, at the age of 16, Dale returned to work with the dredges and quickly became familiar with every aspect of their operation.

His first "real" job at the camp came in 1945 when he was hired as a "mechanic's helper." He was responsible for greasing the heavy tractors, a job generally carried out lying on one's back beneath the belly of the mechanical beast, more often than not in oil and grease soaked dirt. For that he was paid $0.91 an hour! [1] By 1950, Dale was an engineer making $425.00 a month. [2] He continued working at the mines until drafted into the Army Signal Corps in 1952. [3] When he returned to the mine in 1954 as resident manager, his salary was $937.50 a month, quite an increase over what he made as a mechanic's helper. [4] Dale's intimate knowledge of the company and its operations advanced his career rapidly as he went from mechanic's helper to winchman to being in charge of thawing (1950), then resident manager (1954-55), general manager (1956-57) and finally vice president and general manager (1958-60). [5]

Dale and Karen Patty continued the family tradition of taking their children to the mines each season. Dale, Karen and their 9-month-old son, Tom, arrived at the camp on June 16, 1954. It was Karen's first trip to the mines, and was quite an experience for a southern California girl.

When the plane landed at the Woodchopper airstrip, Ted and Sally Murray, the accountant and postmistress for the operation, met them. After transferring the Patty's gear, weekly mail and fresh food supplies for the camp to an open bed truck, Dale climbed in the back letting Karen and Tom ride up front. There they met Harry Gingrich, the camp superintendent, who Karen described as "truly grizzly looking . . . and a really nice old guy." [6]

Before their arrival Woodchopper Creek had flooded washing out the only bridge across it. Still flowing deep and swift when the truck reached the bank, Gingrich knew that it could not make the crossing under its own power. They attached a steel cable to a CAT on the opposite bank and slowly pulled the truck across. Karen notes that "during the crossing and from my vantage point inside the truck, I looked down through the holes in the floor-board and saw the foaming water of the creek-turned-river churning beneath my feet and over the floorboards in the truck's cab." [7]

As described earlier, many of the camp buildings could be moved from place-to-place by dragging them on log skids behind a CAT. In 1950, the company decided to concentrate work on Coal Creek for two years, then shift over to Woodchopper for the 1952 and 1953 seasons. When Dale arrived to take over management of the operation in 1954, the crew moved the camp back to Coal Creek where it remained until 1957. What was to become Karen's first home at the mine is best described in her words:

It was a tiny cabin built of Celotex walls and a tin roof. There was a kitchen with a two-burner, kerosene stove and a little sink. No water, but a sink! The little living room had a pot-bellied stove promising a future source of heat. A tiny bedroom held two twin beds more like army cots, a small chest of drawers, and one corner framed off with plywood to create a closet with a curtain to pull across the front of it. Oh, yes -- there were some scattered boxes piled with items that had been on shelves before the move. Then, there was the floor -- linoleum in the kitchen area that had not taken well to the cross-country trip on the log skid and as a result was a series of loosened and curled-up strips. A mess! [8]

Karen looked at Dale, knowing that he was just itching to get down to his dredge. He had known it all his life and after all, he was home again. With Karen's encouragement, Dale bounded out of the cabin and headed down the road like a school kid.

It was not until years later that Dale found out that Karen had sat and cried that afternoon after he left. [9]

The two of them, working with the dredge crew as needed, began slowly to turn their tiny Celotex cabin with its tin roof into a home. One of the first major additions came the next day, which happened to be their second anniversary, but their first one together. [10]

Although Dale gave Karen a lovely ivory and gold nugget necklace, the really important gift came by way of a hole, dug in their backyard by Harry Gingrich at the controls of a CAT. After fashioning a foundation of sorts over the hole, Gingrich and the CAT came rumbling back down the road with a pre-built, but also pre-used, outhouse chained to its blade. A two holer at that! Gingrich retrieved it from Dale's parents' house above Cheese Creek, just for Karen. No longer would they have to cross the road to use the "public" facilities. [11]

|

| Dale Patty (standing) and Harry Gingrich delivering Karen Patty's anniversary present, a two-holer of her very own. (Dale and Karen Patty Collection, photo courtesy of Dale Patty). |

Within a week, Dale was making changes. For almost two decades, the two camps never had the convenience of running water. That was about to change. At the suggestion of Harry Gingrich, Dale ordered a ram pump [12] for the camp and installed it on a small reservoir just below camp. Using some of the hydraulic pipe and hoses from the old thawing points, he rigged up a system to get water to the front of each cabin. Karen got something special. Her little waterless sink had a spigot coming through the wall so that now all she had to do was turn the knob. No longer did she have to haul it from the creek by the bucket full and no more brushing her teeth in a glass of water. This was almost like city living, almost. [13] They also installed water taps in the cookhouse and several cabins. [14]

THE 1954 DREDGING SEASON

Two challenges faced the younger Patty when he assumed the reins of the companies in 1954. First, finding a suitable shipping company to freight the necessary supplies and materials they needed. (The White Pass Route shut down their operations below Dawson when the U.S. Congress had passed the Jones Act. [15] Patty entered negotiations with Hayes Navigation Co. out of Carmacks, Yukon Territory for freighting services from Dawson to Coal Creek. If the negotiations worked out, Hayes would use the same boat and barge as had the White Pass Route the previous year. [16]

Second, the economics of running a placer operation were starting to catch up with the company. The price of diesel oil continued its steady climb upward so that it now cost an additional ten to twelve cents per gallon more for transportation than it had in 1953. Wages, crew size and food costs were a constant concern. Added to this was the fact that the price for replacement parts for the dredges, bulldozers, trucks and other equipment continued to climb. How far could they cut back in order to maintain their profits, yet still have enough crewmen to work the placers?

The following table illustrates this point by presenting operating costs and dredge repair costs for 1952 through 1956:

Table 9-2. Operating and Repair Costs, 1952-1958.

| Year | Company | Operating Costs | Repair Costs |

| 1952 | Alluvial Golds Inc. | $49,420.50 | $23,282.57 |

| 1953 | Alluvial Golds Inc. | 21,266.24 | 29,160.49 |

| 1954 | Gold Placers Inc. | 49,073.92 | 23,521.71 |

| 1955 | Gold Placers Inc. | 55,817.63 | 24,451.31 |

| 1956 | Gold Placers Inc. | 62,765.66 | 29,099.38 |

| 1957 | Gold Placers Inc. | 65,709.46 | 35,470.42 |

| 1958 | Alluvial Golds Inc. | N/A | 42,981.40 |

Over the next seven years, with the price of gold remaining at a regulated $35.00 an ounce, and with the cost of everything else rising steadily, cutbacks were necessary. The first cut was the Assistant Superintendent, then the mechanic's helper, the dredge line mover and several other positions. Finally the company consisted of a vice president/on site manager, a mine superintendent, an accountant, cook, waitress, mechanic, two CAT operators, and three 3-man dredge crews. One of the amazing things about what transpired at this time is the fact that in 1936, when the dredge was first constructed and operations began, the company employed a crew of 75 to 100 men. They were now holding their own with a crew of 17.

Had the company continued operations after 1960, Patty had plans for cutting the swing and midnight-shift engineers. To accomplish this, they would rework the dredge so the winchman could read the gauges from the winchroom. They would also install shutdown devices in the event that anything went wrong. In addition he was considering cutting the waitress, and since most of the stripping was done, one CAT driver. That would have resulted in a crew of just 13 people, something that would have been unthought of 25 years earlier. [17]

At the end of June, during the first cleanup under Dale's supervision, there were several surprises. First, among coarser then usual gold were two large nuggets, one weighing almost an ounce. Second, was a variety of metal "stuff" including nails, bits of metal, and parts from an old clock. The dredge worked over ground previously occupied by William Beaton's cabin. The cabin had burned, leaving the metal pieces. [18]

In the meantime, Karen was experiencing some "tummy troubles" that eventually prompted a trip to Fairbanks for a check-up. Dale notified his parents to let them know Karen and Tom were coming in for a visit. At that point the camp was no longer using Morse code to transmit between the camp and Fairbanks. They had moved up to a two way voice radio system. Therefore, when he added "Possible family addition," to his message, it went out not only to his parents, but to everyone in the territory with a receiver listening to the "Tundra Topics" that evening. [19] This included everyone in camp who had radios heard it as well. Like any small town, secrets are a hard thing to keep in a mining camp. [20]

During the 1954 season, the dredge worked some unusually rich ground. It worked through the claims originally staked by William Beaton and Nels Nelson in 1907; from just below the mouth of Beaton Pup, to just below that area. [21] Evidence of Beaton and Nelson's early mining included shafts where they had dug down to bedrock and the drifts that they used to follow the paystreak as it meandered. According to Dale, they did much of their drifting in tunnels so shallow that they literally crawled along through the permafrost on their bellies. [22]

|

| Drill crew operating the Keystone drill on Coal Creek (Dale and Karen Patty Collection, photo courtesy of Dale Patty). |

Although the drill testing in the area showed only fair amounts of gold, the actual dredge results revealed some of the richest ground on the creek. Cleanup No. 121 (June 28, 1954) and No. 122 (July 10, 1954) averaged 98.9¢ and $1.029 per cubic yard respectively. Similarly, Cleanup No. 25 (June 30, 1939) -- which contained the results from dredging the ground originally worked by Frank Slaven -- had an average value of $1.03 per cubic yard. [23] How the old-timers were able to locate the pockets of unusually rich ground, without first removing the muck and overburden is anyone's guess.

The ground worked during 1954 was good. It was shallow, averaging 10-1/2 feet deep with firm granitic bedrock below, "perfect for holding gold." The company was making money like it had not for a number of years. So much so in fact that it bothered Dale. He saw the company paying heavy taxes in 1954 and then hurting later. As shown in the following table, the average cleanup for 1954 ranked third overall in the production history of Coal Creek. [25]

Table 9-1: Cleanup Values on Coal Creek, 1936-62

| Year | Total Value of Gold |

Number of Cleanups |

Average per Cleanup |

| 1937 | 152,771.82 | 8 | 19,096.48 [24] |

| 1938 | 261,580.48 | 9 | 29,064.50 |

| 1939 | 354,425.59 | 9 | 39,380.62 |

| 1940 | 290,834.95 | N/A | N/A |

| 1941 | 266,238.75 | N/A | N/A |

| 1942 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1943 | Gold Placers Inc did not operate in 1943. | ||

| 1944 | Gold Placers Inc did not operate in 1944. | ||

| 1945 | 123,130.49 | N/A | N/A |

| 1946 | 136,458.02 | 9 | 15,162.00 |

| 1947 | 158,270.00 | N/A | N/A |

| 1948 | 106,365.00 | N/A | N/A |

| 1949 | Gold Placers Inc did not operate in 1949. | ||

| 1950 | 127,565.32 | 12 | 10,630.44 |

| 1951 | 182,200.89 | 11 | 16,563.72 |

| 1952 | Gold Placers Inc did not operate in 1952. | ||

| 1953 | Gold Placers Inc did not operate in 1953. | ||

| 1954 | 229,124.11 | 9 | 25,458.23 |

| 1955 | 208,154.76 | 10 | 20,815.48 |

| 1956 | 197,001.84 | 9 | 21,889.09 |

| 1957 | 130,553.85 | N/A | N/A |

| 1959 | Gold Placers Inc did not operate in 1959. | ||

| 1960 | Gold Placers Inc did not operate in 1960. [26] | ||

| 1961 | They did not work Coal Creek in 1961. | ||

| 1962 | They did not work Coal Creek in 1962. | ||

With the support of the Board of Directors, Patty made a decision shutting down the dredge on September 19 to keep taxes from devouring their profits. [27] In describing the economics of shutting down early, Patty pointed out that the first $25,000 was taxed by the Federal government at 30%. After that, the tax rate jumped to 52%. To illustrate how shutting down the dredge early actually saved the company a great deal of money, see the following:

| Gross value of gold and silver produced: | $229,602.96 |

| Less depreciation and operating costs: | -160,000.00 |

| Net value (before deducting mint charges): | $68,512.71 |

| 30% tax on first $25,000.00 profit: | 7500.00 |

| 52% tax on the remaining profit: | 22,631.29 |

| Total tax as of 9/19/54 cleanup: | $30,131.29 |

Had the dredge continued working for another four to six weeks, assuming three additional cleanups averaging $29,051.25 (the average value per cleanup of the first eight cleanups), the company would have produced a gross value of $316,756.71. Using the same figures for depreciation and operating costs would leave a net profit of $156,756.71. This would result in a tax liability of $76,013.49.

Although the dredge shut down a month early, management feared that if the crew were let go early they would be impossible to rehire the following season. Because of this, the crew was kept on carrying out "dead work" around the camp that had been neglected for a number of years. [28]

Because the two companies were alternating between the creeks every two years there was a lot of maintenance required to keep the camps in good condition. To accomplish the many tasks facing the crew, Patty divided them into five teams. Each was responsible for a different group of tasks: (1) work on the dredge to get it ready for the 1955 season as well as work on the Woodchopper dredge repairing its pontoons, gearing and rollers; (2) stripping the ground ahead of the dredge; (3) repairing the road from the camp down to the Yukon; [29] (4) construction around the camp including work on the bunkhouses, mess hall and enlarging the General Manager's cabin with the expectation that Dale and Karen had a new addition to their family on its way; and, (5) drilling the remaining three miles ahead of the dredge to determine the scale and location of the pay streak. Taking this approach to accomplishing the work seemed to get a lot more done in the short period of one month. [30]

The ground dug during the 1954 season was well thawed and the gravels were unusually easy to dig. This coupled with shutting down for the season a month early allowed the company to forego re-lipping the bucket line before starting the 1955 season. In his 1954 annual report, Patty announced to the board of directors that, "If the digging continues to be as good next year, the old bucket line should last the full season." This in itself would result in big savings in both time and money. [31]

The average depth the dredge worked during the season was only 10-1/2 feet. At places, the bedrock was less than 3 feet deep, and in some, it reached right to the surface. In order to maintain sufficient water to keep the dredge afloat the crew had to dig these areas down eight feet deep. However, Patty notes in his annual report that some of these high bedrock areas proved to be extremely rich. [32] To prevent having to dig more bedrock than necessary, the area ahead of the dredge was flooded with 3 to 5 feet of water, thus raising the level of the dredge pond. [33]

Always thinking of future seasons, the company had approximately three years of ground stripped and thawed ahead of the dredge. Their plans for the 1955 season included cutting back on the stripping operations on Coal Creek and moving the bulldozers over to Woodchopper. There they would start stripping and thawing in preparation for moving the operations back to that creek in 1958. [34]

THE 1955 DREDGING SEASON

The 1955 mining season for the dredge was by all measure routine. That was not the case for Karen and Dale however. She had given birth to twins. On May 27, Karen and Dale returned to the mines at Coal Creek with their three children, the four month old twins, James and Stephen, and Tom who was now 20 months. According to Karen, "Don Holshizer flew like raw eggs were loose in the plane, he was so careful. He even circled a rain squall and came down unusually slowly so as not to bother the babies." Among the many tasks to deal with upon their arrival at the camp was building something to keep Tom, who was by now mobile, out of harm's way. To do this, Dale used several of the old thawing points, cut them to five-foot lengths driving them into the ground as fence posts. Around these, he hung three-foot high chicken wire to create a 15' x 25' "play pen" alongside the house. [35]

It was as though the 1955 season was a harbinger of things to come. Harry Gingrich, the charismatic superintendent at the mine, became seriously ill. A helicopter, chartered by the General Petroleum Company that was basing some prospecting work out of Coal Creek camp, flew him from Coal Creek to Woodchopper. From Woodchopper, Gingrich flew by plane to Fairbanks where his condition deteriorated to critical. Flo Gingrich, Harry's wife and the camp cook, joined her husband in Fairbanks.

Harry Gingrich passed away a week later. He was one of the few men who had been with the company since its beginning in 1935. [36] Dale commented that with Harry's death, his world appeared to come crashing down around him. "Not only did I lose one of my best friends and teachers, but more importantly the mine lost the finest superintendent that it could possibly have had." [37]

Bill Finnigan, assistant mine superintendent was promoted to replace Gingrich. Although he lacked the experience of Gingrich, Finnigan tried to run the operation as best he could.

The dredge started work on June 5th, almost two weeks later than usual. This was due in part to a very late spring leaving the gravels frozen until June 2nd. In addition, when the crew floated the dredge off its winter storage shelf, they found trouble with the pontoons which required three days to repair. The overall record for the year was somewhat depressed. The dredge ran for a total of 138 days working at 97.5% efficiency. During that time, it processed 355,600 cubic yards of gravel that averaged 54.4¢ per cubic yard, down from the 75.3¢ the season before. [38]

This was the last season either of the dredges broke the $200,000.00 mark for seasonal production. In 1955, the Coal Creek dredge recovered $208,643.02. After the close of the season, between $8,000 and $10,000 dollars remained frozen in the side sluices that would be recovered the following year. [39]

One point that Patty made to the Board that fall was the fact that although the company's production was down by nearly $21,000 from the previous year, their "operating costs were also substantially reduced." [40] Two things affected their operating costs. First, the company purchased a new International TD-24 bulldozer at a cost of almost $30,000, including freight. [41] According to Patty, the new TD-24 was capable of doing the work that had previously taken two or three TD-18s to accomplish. They planed to use the TD-24 almost exclusively for stripping. Moreover, because it could handle so much more, they were able to get by with only one CAT driver. The second driver transferred to the position of shoreman. This would enable him to use a TD-18 to accomplish any bulldozer work that might be necessary around the dredge, the pond and the camp such as building dikes in front of the dredge to raise the water level. This CAT was also used for moving dredge lines and hauling. [42]

In late 1955, the company fabricated a rectangular steel tank to fit on the Athey wagon. [43] It measured roughly 12' 6" wide and 5' high, and held approximately 2,500 gallons of diesel oil. From that time forward, they hauled all diesel fuel using the Athey wagon. The decision to build the tank on the Athey wagon was a good one. When in 1958 the company moved the operation to Woodchopper, they added almost 12 miles to the trip. Hauling fuel in barrels, with trucks, would have been a huge undertaking because the road from the camp at Beaton Pup along the hillside to Slaven's Roadhouse was no longer passable with heavy equipment. [44] Begining in 1957 access from camp to the river for supplies, etc. was via a route that followed Coal Creek, on the right limit.

The problem of transporting supplies and materials continued to plague the company. To remedy this, in part, they reached an agreement with Standard Oil Company of California to purchase two 2500-gallon storage tanks and one 5000-gallon tank. [45] Under the terms of the deal, Gold Placers Inc. would pay half of the cost of the tanks over a five-year period and Standard Oil would pay the other half. This enabled them to cut their freighting costs from one cent per pound to three-quarters of one cent per pound. In addition, the company realized a substantial saving because it no longer needed to back haul empty barrels at one dollar per barrel. In order to receive these benefits however, the company had to agree to buy only Standard Oil products for the next five years, "provided the mines are operating." [46]

One of the other low points of the 1955 season was an accident that occurred at Slaven's Roadhouse. Several crewmen, including the aging Phil Berail who, like Gingrich had been with the company from the beginning, were riding in the back of the truck. Dale was driving. Patty called to the men to be careful and stay put because he was going to pull the truck forward. Berail either failed to hear the warning or failed to heed it. He started to jump off the truck as it started to move forward and stumbled hitting the ground hard. This time after he got up and tried to tell the others that he could walk back to his cabin no one believed him. They took him immediately by truck to Woodchopper and then flew him into Fairbanks where he was hospitalized for a fractured hip. [47]

The outlook for 1956 was strong. They had retained three quarters of their crew from 1954 to 1955 and they hoped to have them back again in 1956. But Patty notes in the annual operating report that although the company carried a good inventory of supplies and spare parts, there would be a "considerable amount of work to be done on the screen, digging ladder, pontoons, and diesel engines next spring." [48] During the time that Dale ran the mimes, the company never needed to borrow money. As is the case of most small companies, the secret to success is a positive cash flow.

|

| Creek Camp No. 3 (c. 1954-57), located on Beaton Pup. The Patty's house is located at the lower right of the photo. Other prominent structures include the assay office (left center, behind the birch tree), mine manager's office (to the right of the assay office), mess hall (right center of the photo), "bunkhouse row" angles away from the mess hail to the left rear of the photo (Dale and Karen Patty Collection, photo courtesy of Dale Patty). |

THE 1956 DREDGING SEASON

As Patty predicted, the 1956 season began on Coal Creek with five weeks of maintenance work overhauling the dredge. Spring arrived early that year so the crew rushed repairs to get the dredge into production as early as possible. The dredge began working on the afternoon of May 26, nearly two weeks earlier than in 1955. The company hoped to get a full 150 days into this season, but cold weather forced them to close on October 14, after only 141 days.

During the season, the dredge worked 358,000 cubic yards of gravel that averaged 55.3¢ per yard as compared to the 58.9¢ per yard the previous season. The production for the year was valued at $197,479.03, also below that of the previous season. However, one advantage of the early cold, Patty estimated between $7,000 and $9,000 of gold remained frozen on the dredge in the black sand. They would recover this and send it to the mint the following spring. This practice generally carried the company through the initial startup phase of the next season, until the first cleanup. Consequently, they would not have to borrow any money from the bank to get the next season going. [49]

Operating the dredges at Coal Creek and Woodchopper had been a tenuous balancing act since WW II. By early June, two men had already left Gold Placers Inc. taking construction jobs in Fairbanks and on the DEW Line. These jobs at twice or more what they were earning on the creeks, tended to draw off the best people and they were virtually impossible to replace. In late June, four older employees, including Flo Gingrich (widow of Harry Gingrich the former superintendent), Les Gingrich (brother of Harry Gingrich and chief engineer on the dredge), Tim Timmerman (a CAT driver) and Jim Peterson threatened to leave if Bill Finnigan were not removed from his job as superintendent at the camp. Patty tried his best to convince them to change their minds and stay. He was able to get them to give him two weeks to solve the problem. He finally relented allowing them to leave, after all, he was the manager and was not going to be pushed into making any rash decisions, on anybody's part, especially his. It was a decision made on "Who was going to be the boss of the operation." [50]

In August, Patty found Roy Nay, a winchman, sitting on the steps of one of the bunkhouses. From a distance, he found nothing seemed out of the ordinary, except for the rifle lying across his legs. Upon investigating, Roy was rambling on, having a nonsensical conversation with himself. Dale decided that something was definitely wrong. Because of the weapon on Roy's lap, Dale took his own rifle, carrying it in a relaxed, non-threatening manner, ever vigilant of the potential danger and ready to use it if need be, he approached the seated winchman.

Slowly walking up to him, Dale called out "Hi Roy, how are ya?"

Dale continued talking to him as he approached closer and closer until finally he was standing right in front of the man. The winchman made no resistance as Patty took his rifle out of his hands and said; "Now Roy, you're going to have to go into town."

Nay replied simply, "Oh that's fine Dale. I'll go into town."

Patty, in later reminiscing about the scene stated "I never had a plane here so fast in my life." [51]

Although it seemed like the company was falling apart around him, Dale noted in the Operating Report to the Board of Directors, "the majority of the work was carried on by a few men who were more experienced and they turned in a very good job." It was impossible to replace Nay as winchman. Because of this the two remaining winchmen worked longer shifts making up for the missing man. Patty also worked a minimum of four hours at winching each day in addition to his regular duties to take up the slack. [52]

Patty discussed the problems of hiring qualified, experienced individuals in light of the economy of the day, in his report to the Board of Directors. He also suggested that the remaining winnchmen "be offered a raise in pay, based on seniority, to try and insure they remain with the company." [53]

Life at the camp was anything but dull. One day, the camp dog named Keeno was runing loose when he ran into a porcupine. As is generally the case, Keeno came out of the encounter with a face full of quills. After diner, a group of men tried to pull the quills out with pliers and the frightened dog just about went wild. Susie Paul [54, a native from Eagle who drove one of the CATs, took him quietly aside and the dog laid perfectly still for him while he pulled them all out, even those inside his mouth. [55]

Keeno was not the only "pet" living at the mine. Les Gingrich worked all summer as the chief engineer on the dredge. The highlight of his season actually came when the last of the crew left the mine each fall and he then took on the mantle of winter caretaker. Dale Patty tells of him complaining about never seeing the sun from mid-November until mid-February. His only company was "a couple of dogs he never used and a cat named Bozo." [56]

Bozo was probably the most unusual cat in the world. The Patty family got the cat in 1938, and according to Dale:

He was tough from the start. One time in 1939, I heard a big husky yelping in front of our home in Fairbanks. I looked out the window and here was Bozo, on the dog's back, claws dug in, riding the Husky down the block.

In 1939, some person beat the cat with a club and we [thought] he would die. He was really beat up. My mother fed the cat with an eyedropper for about 2 weeks. The cat recovered, but one eye was gone.

Then in 1940, we decided to move to Seattle. What to do with the cat? Dad decided to take it to the mine. I am sure he [thought] the cat would live a very short time out there. When I came back in 1945, he was there, but would have nothing to do with me. He was the biggest, most independent animal I have ever known. He ate what he wanted and was no one's friend during the summer.

I am told by Les Gingrich, that during the winter, when he lived with Les, he was often attacked by wolves. He would get on the wolf's back and ride him all over camp. Finally in about 1953, the wolves figured him out and a pack attacked him and killed him.

What a cat. I guess this cat is a little bit like the old timers that settled those creeks. [57]

While the men at camp spent their days and nights working on the dredge, moving muck with CATs and any of a dozen other heavy jobs, Karen Patty, with her three young boys worked every bit as hard as any man on the crew. She describes her daily routine in her unpublished memoirs as:

Dale brings pancakes and a pot of coffee back from the cookhouse at 6:30. I get up and eat, usually before I get the boys up. Get stove going and water for wash heating. (I tried washing every other day, but it was no good).

I had to get a fire going in the pot-bellied stove in the middle of the living room, no matter how hot the day might prove to be, as well as a fire in the small kitchen stove. On both stoves I put buckets of water, somewhat overhanging the stove surfaces.

Then I got the boys up, fed them, got them on and off the toidy seat (potty) -- always a gamble as to whom to put on first and who could wait the longest before I had a nasty diaper to contend with. Soon as possible, I got them all out in the yard.

Did the dishes, then assembled the table (used their feeding table with the seat folded down out of the way in the center for this), the washing machine (a 7 gallon machine ordered from Montgomery [Wards]), a box to hold rinse water, the tub and 7" hand-wringer, and the clothes for washing. While loads went thru, I made beds and cleaned the house. The washing machine would hold 7 diapers at a time -- this was long before the days of disposable diapers. By the time the clothes were hung out on the line (on dry days) and all the washing equipment was put away, it was just in time to get the twins in to change them and wash them up before feeding them here at the house. Then we all went down to the cookhouse for lunch. The twins were in their teeter-babes [58] and fed tid-bits by Flo.

Back to the house to put the twins to bed. When Dale was in the area, he would play with Tom and put him down for a nap in our bed. Usually the twins were up first and put out in the yard, followed by Tom.

Late afternoon, I always "dressed" for dinner, got the twins in for their dinner; then we all went [to the cookhouse] for our diner. Afterwards there was pandemonium as the boys played in the house. At 7:00 pm, it was finally bath time and then bed for the boys at 7:30, when we were lucky. [59]

The labor problems on Coal Creek had a profound affect on both creeks. Because skilled crewmembers were so difficult to find the company paid little attention to stripping or thawing on Woodchopper. The problem with several thousand feet of ground ahead of the Woodchopper dredge was that the ground thawed naturally and thus was never drilled. In thawed ground, the drill crew must place casings in the hole to keep it from caving in on itself. Frozen ground eliminates this need. Even with the use of casings, the results are questionable. [60]

Likewise, they delayed repairs to the Woodchopper dredge pontoons because work on the Coal Creek dredge was more pressing. [61] The pay streak pinched down to a narrow area of the creek. Consequently, the dredge moved rapidly downstream to a point where, by the end of the season, it passed the last reliable drill line put in before 1956. From here, it went into an area where the drilling showed poor results. At the close of the season, there was one more line, approximately 2,000 feet below the dredge but the results of this line were poor. The company hoped that by the end of the 1957 season there would be a good estimate of how many dredging seasons remained on Coal Creek. This is one of the first times the anual operating reports considered that the end of the paystreak and thus the end of the mine was near at hand. [62]

As an example of the difficulty the company had attracting experienced crewmen, they were unsuccessful at trying to hire a driller before the start of the 1956 season. In their desperation, they decided to train a man for the job. A former employee, who was working in Fairbanks agreed to come to the mine for a week at the end of June to serve as a trainer. After getting the new employee trained so that drilling could begin in early July, the man quit in late July. He left for a higher paying job on the DEW Line. They promoted the drill helper to driller where an experienced paner trained him to do the job. By the time he was competent at the job, they wrote off the first line put down as "practice." When they put down a second line, 500 feet below the previous one, more problems cropped up. First, the drill clutch broke. The crew repaired it temporarily and ordered a new one. Before the new clutch arrived, the temporary repairs gave out and it failed a second time causing damage to the engine bearings. Three weeks later, the new parts arrived. [63]

|

| Keystone drill in operation on Coal Creek (Dale and Karen Patty Collection, photo courtesy of Dale Patty). |

With the clutch repaired, work continued for only a short period until the bit jammed at the bottom of a 37-foot hole. Try as they did, the crew could not work it loose. They borrowed a second bit from another mining company and drilled a new hole along side the first in an attempt to break the bit loose. Unfortunately, the season ended before they could free the bit. The crew felt certain that with the next season the bit would come out without much difficulty. [64]

An overall feeling of despair started creeping into the annual reports beginning in 1956. The company was plagued with an inability to compete against the high wages being offered elsewhere. The value of the ground the dredge was working was steadily declining to where it was only slightly higher than 50¢ per cubic yard. The company had seen lean gravels in the past and always seemed to work through them to richer ground. Now, with the price of gold still frozen at $35 an ounce, ever increasing problems with hiring and keeping experienced crews, the end was relentlessly creeping into view.

THE 1957 DREDGING SEASON

The 1957 season brought with it more problems for the Coal Creek operations, even before the crews arrived in the spring. Alaska's weather is fickle at best. Rarely are winters, or summers for that matter, consistent. At some point during the winter of 1956-57, Interior Alaska temperatures rose rapidly from -20° F (-28.8°0C) to +40°F (4.4°C) in the space of a few days. This chinook [65] brought with it heavy rains in mid-winter. The melting snow sent a flood surging down Coal Creek washing out the dike in front of the dredge. This released the water under the ice in the pond that was insulating the already thawed gravels. When the temperatures turned cold again, a large glacier filled the dredge pond covering the exposed gravels. Consequently, the frost penetrated, this time deeply. Because of the amount of ice before the dredge, both in the pond and covering the gravel, the crew was eight days late getting it into operation. They spent the first three weeks of the season fighting the heavy frost in the gravel. Dale Patty commented that, "at times the dredge felt like a bucking horse beneath your feet as it hit pockets of frozen gravel." [66]

In addition to the freakish winter weather, labor problems continued to plague the company. During the winter, injuries hospitalized their best winchman and prevented him from returning for the season. The other two winchmen decided to go into construction work because of the higher wages. This meant training three new winchmen. The problem was compounded by the fact that every year there were fewer and fewer dredges operating, so experienced dredgemen were hard to come by. One of the new winchmen had some previous experience, but it was not up to the level of the people the company was able to hire in the 1940s and early 50s. [67] After losing the third winchman, Patty was filling in with a four-hour shift from 4 pm to 8 pm, after working his regular duties as manager. This meant the other two winchmen only had to work 10 hours a day instead of 12. At that time, it was impossible to hire additional winchmen. No one was around although most of the dredges had already shut down. [68]

The dramatic drop in the amount of gravel dredged reflects the inexperience of the winchmen. During the period from 1952 to 1957, the dredging season lasted an average of 138.6 days. During that time, they processed an average of 346,533 cubic yards of placer material. In 1957 however, during the 140 day season, only 305,200 cubic yards was processed. This was nearly 14% less for roughly the same length of season. Experience still counted and experienced winchmen were impossible to find.

When the 1954 dredging season is factored out the differences between seasons becomes even more dramatic: [69]

| 1952-56 Averages (Excluding 1954) |

1957 | |

| Length of Dredging Season | 144 days | 140 days |

| Yards Dredged | 367,250 yd3 | 305,200 yd3 |

| Average Yards per Day | 2550.35 yd3 | 2180 yd3 |

According to people who worked on dredges, you became accustomed to their constant noise so that you did not even notice the continuously rumbling din in the background. At least you did not notice it until it stopped. Then you knew something was wrong. If it stayed quiet for a long period, something was really wrong.

At about 8:00 in the evening of June 22, the first thing people noticed was the silence. Then the camp suddenly filled with a commotion of trucks and men runing about gathering pumps and hoses. This could mean only one thing. The dredge was going down. [70]

Earlier that morning, the crew replaced the original bucket chain with a heavier one. To counter-balance the additional weight on the digging ladder, the crew added water to the rear pontoons. The winchman was digging too heavily causing the bow of the dredge to rise and the stern to sink deeper. At the same time, Virgil Wasser, one of the crewmen, had been checking the pontoons leaving the hatches open as he went from one to another. [71] Water rushed over the stern filling the open pontoons. A large bolt broke between two pontoons allowing them to fill rapidly with water compounding the problem. The dredge began to list to the port side. The quick thinking of the engineer averted major damage when he shut down the diesel engines before they went under water. [72]

When the men from the camp arrived at the scene, they found it almost supernatural. The night was pitch black. Although with the diesel engines shut down, the light plant was still above water produced electricity for the lights now shining beneath the dredge pond. Every now and then something would slide off one of the workbenches or fall from an upper deck clattering on its way to the bottom. Dale Patty commented that it was "eerie." It sounded "just like a ghost was out there throwing things." [73]

Several years earlier, late in the season, the Woodchopper dredge suffered a similar fate when the winchman applied the brake too quickly and too hard while swinging it back for another pass at the face. The sideways force of the digging ladder caused the dredge to tilt to the starboard side. Normally it operated with less than a foot of freeboard. [74] The top heavy nature of the Walter Johnson dredges carried it further and further to the right until water rushed over the side of the hull filling the right pontoons. This just exasperated the tilt and the dredge went over, almost onto its side. [75]

In both cases great care was necessary so as not to capsize the boats. Had either dredge rolled, the damage done could have been tremendous. Probably the only thing that prevented the dredge from rolling over on its side was the sand at the back of the dredge that kept the stern more level. [76]

Carefully surveying the situation, Patty chose a point and directed the CAT driver to carefully cut through the dike lowering the water level in the pond. In the case of the Coal Creek accident, they only had to drain about five feet of water letting the dredge settle onto the bottom. [77] Using every pump available between the two camps, they pumped out the pontoons and the reflooded the pond. After draining, cleaning and reassembling the diesel engines, the dredge was back in action within 35 hours of sinking. At the same time, Patty took advantage of the down time to carry out a cleanup. [78]

Righting the Woodchopper dredge posed a greater problem. The dredge face was nearly ten feet higher than that at Coal Creek and the pond was considerably deeper. Ernest Patty was at the camp at the time and directed the operation to re-float the dredge. Taking a level, Patty went downstream and found the point where the water would just drain out of the pond. He had the CAT driver cut a drain below the dike. When that was completed, he breached the dike allowing the water to flow out lowering the pond. After calculating the drop of the valley in front of the dredge, the fall of the creek was not sufficient to drain the pond. Roughly two feet of water remained on the starboard side of the bow deck after the dike was broken, with the dredge deck still below water. [79]

Patty ordered cofferdams [80] to be built that would fit over the pontoon hatches. They painted heavy pitch on the bottom of each cofferdam before positioning it. This sealed the bottom to the deck leaving the top of the dam above water. Carefully, working in sequence, they pumped some water from each pontoon, then repeated the sequence. If they took too much water out of any given part of the pontoons at one time, the result would be to wrench the hull, possibly compounding the problem by pulling bolts, etc. Slowly the dredge began to right itself until finally the pontoon hatches were above water and the cofferdams removed. The dredge was again on an even keel. In this case, it took three days until the dredge was again upright. [81]

|

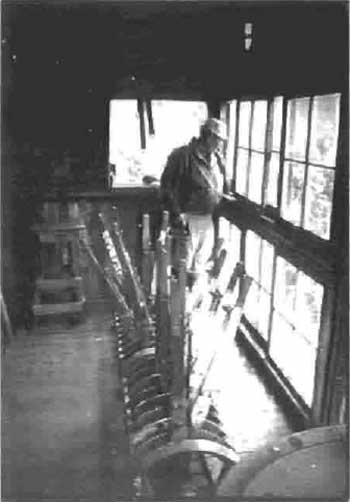

| Dale Patty (right) and Ted Murray (left) placing a retort vessel into the furnace to drive the mercury off the gold amalgam (Dale and Karen Patty Collection, photo courtesy of Dale Patty). |

Not only did the dredge cause a great many problems during the 1957 season, so did the CATs. It was not unusual to find one of the big tractors out of commission for a day or so, either due to general maintenance or outright breakdowns. However, this season they seemed to have more than their share of problems.

By this time, the company was working with two International Harvester TD-18s and a new TD-24. The company purchased the TD-24 in 1955 as a replacement for one of the aging TD-18s. The company expected the larger and more powerful bulldozer to pay for itself within a few years through significant savings in labor and material costs. According to that year's anual operating report, the first year alone the company saved "thousands" of dollars on materials that would have been required to maintain the ailing machine it replaced. However, by late in the season, problems with the hydraulics that operated the new bulldozer's blade forced the stripping operations to slow considerably. International Harvester promised to send a representative out the following spring to get the new machine back up and runing before the start of the mining season. [82] This was only the begining of what Karen Patty later came to call "The Farce of the Cats." [83]

The International Harvester representative did come to Coal Creek early in 1956 and worked on the troublesome TD-24. When he left the machine was working. Soon thereafter, the old problems started cropping up again. By July, the bulldozer was already stuck in the mud. Two months later it started exhibiting more mechanical problems. The men started tearing it down and rebuilding it on September 5. They replaced the clutch on September 10 and an equalizer spring on it by mid-month. It was finally back to work by the 28th, almost too late since the dredge shut down for the season on October 16, 1956. [84]

By late May in 1957, the TD-24 was down again, along with one of the TD-18s. Before they got them back up and working, the remaining TD-18 that was supposed to be working with the drill crew downstream on Coal Creek limped back to camp. Having all three CATs down so early in the season was a serious problem, especially since the water was runing high in the valley. Later the same day, the light plant went down. It was not a good day at the camp. However, as was generally the case, by pulling together and tackling the problems head-on, one of the CATs was running after diner, and the lights came back on soon after. [85]

The next month, almost four weeks to the day, the blade on the TD-24 again decided to stop working. Also, Susie Paul's TD-18 was stuck in the creek. Dale and Paul got the TD-24 back on its tracks and headed down to pull the TD-18 out of the creek. As he tried to run to help, Dale's feet sank deep into the soft, sticky mud. His momentum carried him forward and "SPLAT' he fell face first into the muck. The air temperature was about 20 degrees above zero and the muck was about 33 degrees. After pulling himself free from the cold, wet ooze, he stayed for over an hour until they could get the TD-18 out of the muck. [86]

The International Harvester Company sent a representative out to the mine three times to attempt to fix the hydraulic system for the bulldozer blade. They finally had to re-engineer the pump. After that, the TD-24 worked perfectly, except for normal maintenance problems, until the company shut down in 1960. [87]

The season was as hard on the people at the camp as it was on the machinery. In June, Jim Patty, one of Dale and Karen's twin sons, let out a howl from the bedroom. Karen ran to investigate finding his thumb caught in the hinge side of the door. Camp first aid was not enough to repair the damage so they ordered a plane to take the family to a doctor in Fairbanks. Woody Clyburn cut his hand severely enough to require medical treatment, again in Fairbanks. Susie Paul, the CAT driver was periodically plagued throughout the summer with a serious rash on his face and neck. He went to go to Fairbanks for treatments following which Dale Patty added another hat to his already overburdened repertoire of tasks when he had to play the role of doctor giving a shot every night after diner. The shots did not cure him and Paul had to fly to Fairbanks again. At the end of September, one of the engineers was stricken by terrible stomach cramps that required a plane to come to camp to take him to Fairbanks. Paul came back to camp with the plane. As it turned out, he had been suffering with pleurisy, pneumonia AND yellow jaundice for most of the summer. [88]

In July, Dale Patty wrote to the Board of Directors informing them of the increasingly obvious fact that the operations would have move to Woodchopper in 1958. Among the reasons he cited were the continuing problems with the CATs (the TD-24 was down for five of the 12 months the company owned it). Moreover, that summer, the serious lack of rain put the stripping operations at Coal Creek behind schedule. It was obvious that they really needed to have crews at both camps, but the reality of the situation and the consistently low price paid for gold made the thought of having a second crew unfeasible. On the other hand, making a move over the hill to Woodchopper posed a variety of problems. Including the fact that the machine shop had no machinery in it. It was all at Coal Creek. Many parts of the Woodchopper dredge had been removed and put on the Coal Creek dredge to keep it running. And the cabins at Woodchopper were few in number and in serious need of repairs. [89]

The end of the season brought with it less than stellar results. As shown by the following tables, Gold Placers Inc. had its third worst year in 1957 with a total production of only $130,874.44 in gold and silver. Four things were to blame. First, the average value per cubic yard had dropped from 55.2¢ in 1956 to 41.8¢ in 1957 or a drop of 13.4%. Second, the paystreak at this point began breaking up into two strands with very little gold in the middle. Company management had to decide what the best way to approach the problem would be. Third, the combination of labor problems, with experienced crews leaving, and training inexperienced crews on the job led to reductions in the quantity of gravel dredged. Finally, the continuing problem with the machinery ranging from the dredge sinking to the "Farce with the Cats."

Figure 8-1: Operating Costs, 1952-5 [90]

| 1952 Alluvial Golds Inc. |

1953 Alluvial Golds Inc. |

1954 Gold Placers Inc. | ||||

| Costs | Cost / Yd3 | Costs | Cost / Yd3 | Costs | Cost / Yd3 | |

| Shutdown, Airport, Camp | $4,912.09 | 0.0140 | $5,220.84 | 0.0128 | $10,978.75 | 0.0360 |

| Stripping, Thawing, Prospecting | 15,146.84 | 0.0432 | 17,440.13 | 0.0427 | 28,236.14 | 0.0926 |

| Dredge Operations | 49,420.50 | 0.1412 | 21,266.24 | 0.1502 | 49,073.92 | 0.1609 |

| Dredge Repairs | 23,282.57 | 0.0665 | 29,160.49 | 0.0715 | 23,521.71 | 0.0771 |

| Subtotal: | 92,762.00 | 0.2649 | 67,866.86 | 0.2772 | 111,810.52 | 0.3666 |

| Administrative | 23,822.43 | 0.0681 | 37,911.69 | 0.0929 | 41,529.37 | 0.1362 |

| Depreciation | 5,728.77 | 0.0164 | 5,616.55 | 0.0138 | 5,602.66 | 0.0184 |

| Total Costs: | 122,313.20 | 0.3494 | 111,395.10 | 0.3839 | 158,942.55 | 0.5212 |

| Value of gold and silver: | 149,634.79 | 173,895.59 | 236,664.23 | |||

| Less Costs: | -122,313.20 | -111,395.10 | -158,942.55 | |||

| Profit/Loss: | $27,321.59 | $62,500.49 | $77,721.68 | |||

| Yards Dredged | 350,000 | 408,000 | 305,000 | |||

| Days Dredged | 142 | 156 | 116 | |||

The company knew from their previous drilling that they would run into an area of low values during the end of the 1957 season. The dilemma was that the company could not work both limits because the center section was so barren that it would dilute the values to a point wiping out any profit. The company made a decision to cast off the higher valued, but narrower streak on the right limit. Instead, the crew concentrated on the left limit where they estimated there was approximately 220,000 to 250,000 cubic yards of material they could work at a profit. This led the way to richer ground further down the creek. [91]

Figure 8-2: Operating Costs, 1955-57 [92]

| 1955 Gold Placers Inc. |

1956 Gold Placers Inc. |

1957 Gold Placers Inc. | ||||

| Costs | Cost / Yd3 | Costs | Cost / Yd3 | Costs | Cost / Yd3 | |

| Shutdown, Airport, Camp | $ 5620.14 | 0.0158 | 5,192.20 | 0.0146 | $ 7,491.36 | 0.0268 |

| Stripping, Thawing, Prospecting | 23,898.96 | 0.0673 | 27,888.01 | 0.0783 | 15,965.44 | 0.0570 |

| Dredge Operations | 55,817.63 | 0.1572 | 62,765.66 | 0.1763 | 65,709.49 | 0.2349 |

| Dredge Repairs | 24,451.31 | 0.0689 | 29,099.38 | 0.0817 | 35,470.42 | 0.1267 |

| Subtotal: | 109,788.04 | 0.3092 | 124,945.28 | 0.3509 | 124,636.71 | 0.4454 |

| Administrative | 39,743.29 | 0.1120 | 39,284.78 | 0.1100 | 40,623.35 | 0.1451 |

| Depreciation | 19,148.36 | 0.0539 | 19,870.13 | 0.0558 | 20,244.86 | N/A |

| Total Costs: | 168,679.69 | 0.4751 | 184,100.19 | 0.5167 | 185,504.92 | 0.5905 |

| Value of gold and silver: | 207,575.56 | 196,469.31 | 130,874.44 | |||

| Less Costs: | -168,679.69 | -184,100.19 | -185,504.92 | |||

| Profit/Loss: | $ 38,895.87 | $ 12,369.12 | $ 54,630.48 | |||

| Yards Dredged | 355,000 | 356,000 | 305,200 [93] | |||

| Days Dredged | 138 | 140 | 140 | |||

By the end of the 1957 season, the company decided operations would shift back over to Woodchopper in 1958, in part due to the decline in values in the gravel in the lower Coal Creek valley and the fact that gold still remained valued at $35.00 an ounce. The annual operating report for 1957 notes that testing carried out on the ground below Pendergast Creek added almost a million dollars to the company's gold reserves on Coal Creek. However, until the price of gold rose, getting to it would be difficult. Consequently, they placed the Coal Creek dredge on a gravel shelf with no dikes below it to impound water. Here, sitting high and dry, it would be safe from glaciers and floods until, and if, the company moved back to Coal Creek. [94]

Although the company operated at a loss in 1957, they were still able to pay a small dividend of $10,000 divided amongst the shareholders by carrying some of the loss over to the following year. [95] When the dredge shut down in mid-October. Nobody realized that this would be the last time the Coal Creek dredge would operate with either Gold Placers, Inc. or the Patty family at the helm.

THE 1958 DREDGING SEASON: WORK SHIFTS TO

WOODCHOPPER CREEK

Dale Patty, Suzie Paul and Harry David arrived at Woodchopper at the end of March, to start preparations for moving the operation from Coal Creek back over the hill to Woodchopper. They also needed to move four buildings from Coal Creek to the other camp, including the Patty's house.

When they arrived at camp, the winter watchman Les Gingrich, the brother of former superintendent Harry Gingrich, joined them. During the summer, Gingrich worked as the chief engineer on the dredge. Dale describes Gingrich as a loner, "The exact type, as the early prospector who came to these creeks in the early 1900s and lived a life alone." [96]

Before landing on the Woodchopper airstrip, Patty had the pilot make several passes between Coal Creek and Woodchopper in order to find the best route for the CATs to take moving the buildings. They knew ahead of time that the road between the two camps was too narrow in places and thus would not provide a feasible route. The previous summer, David Hopkins of the US Geological Survey, [97] used Coal Creek as a base of operations for conducting a study of the area. He brought with him aerial photographs of the drainages that he and Dale used with stereoscopic glasses (providing a three-dimensional effect) to search for the gentlest pass over which to move the camp buildings the next season. This saved a lot of legwork as well as trial-and-error in the end. They eliminated Pendergast Creek along with Little Snare Creek. The two remaining routes were either Snare Creek, about a mile above the camp, and another, six miles farther up Coal Creek that dropped down into Mineral Creek (a tributary of Woodchopper Creek) on the other side. [98]

Dale and Harry Patty took one of the bulldozers to clear the snow from the road between the two camps. After coming over from Woodchopper, at a point within a mile of Coal Creek camp, the tractor ran out of fuel. Jumping off into waist deep snow, the trio had to hike the rest of the way to camp through heavy, wet snow. The next morning they hauled diesel fuel, in five-gallon buckets, back to the dormant tractor. After getting it back up and running, they decided to cut a path over to Martin Adamik's cabin to see how he had faired the winter. [99]

When they arrived at his cabin, they found him lying in bed, looking poorly. True to his nature, as soon as the trio entered he started his non-stop talking, continuing for about an hour. At that point, he turned, looked at Dale, and said "Dale, I'm through talking now." With that one simple statement, he closed his eyes and died. [100]

Over the course of the next several weeks Susie Paul used a bulldozer to excavate a grave on a small rise not far from Adamik's cabin. The men then retrieved his body with its canvas shroud from its temporary resting-place in a snow bank and laid Martin Adamik to rest above his beloved creek. [101]

The company had constructed most of the buildings at Coal Creek on log skids with the intention of using a CAT to drag them from place to place. However, those they needed to move to Woodchopper did not have skids on them. Among these was the house the Patty family lived in, Karen's "tiny cabin built of Celotex and a tin roof." [102] Because of the additions added over the seasons, the crew had to divide it into pieces in order to move it.

The men made two large sleds out of logs, bolted together, to support the buildings. Each structure was then jacked up and the sled positioned beneath it. One CAT pulled the sled with the other following behind to slow its downhill progress preventing it from over-running the tractor ahead.

They moved four buildings to Woodchopper camp followed by most of the supplies and inventory of replacement parts. Even at that, Patty commented, "It seemed all that sunmer we thought of something else we [needed] from Coal Creek." He continued with, "This was a new adventure in my life, and I learned an awful lot about moving and about people." [103]

Getting the dredge up and running took a lot of work. It had sat idle for the previous four seasons and much of its machinery had been "robbed" and taken to Coal Creek to keep that dredge running. [104] Now, all of it had to be removed from the Coal Creek dredge and brought back to Woodchopper. Compounding the problems was the fact that over the winter the Coal Creek dredge had been "glaciered in" when floodwaters coming down the creek froze covering the hull. There was two feet of ice on and above the deck at the bow and nearly four feet at the stern. The ice entombed the two diesel engines, the pumps and most of the tools on the dredge. Even if the company had wanted to work Coal Creek that season, it would have been nearly impossible to start until well into June. [105]

One advantage that the crews had on Woodchopper over Coal Creek was that the stripping operations had continued for the previous four years without the dredge operating. Unlike the situation on Coal Creek where low water years and breakdowns on the part of the CATs had put the stripping operations way behind schedule, the Woodchopper dredge had several years of stripped ground ahead of it. In addition, the depth of the gravels on Woodchopper was greater than that on Coal Creek, thus the forward progress of the dredge would be slower.

The Woodchopper camp had not been used since 1953. One of the first things the crew did was to put in a water system similar to the one at Coal Creek using a ram pump and the old hydraulic hoses to get water to each of the cabins. This made life much more livable for everyone.

The company used a great deal of wood to heat the cabins and mess hall, in addition to a huge amount used during the last month of the season to fire the boilers on the dredge. They also had difficulty in keeping someone at the camp over the winter to cut cordwood. To remedy this problem they decided to replace the old wood-burning stoves with new oil stoves at Woodchopper. They ordered heavy gauge steel, fashioned a rectangular tank capable of carrying 2,500 gallons of diesel oil, and placed it on top of the they wagon. [106] By this time, the road from Beaton Pup to the Yukon River was almost impassable. To get the CAT and wagon with its attached oil tank to the holding tank on the riverbank where the company's supplier dropped off shipments, the CAT followed the road from Woodchopper, over to Coal Creek and down to the camp at Beaton's Pup. From there, they would follow the tailings to where the dredge sat and then over the stripped ground as far as they could. At that point it was only a short distance through the creek to the Yukon. The lower road at Coal Creek follows roughly this same route, even today. From there, the CAT retraced its tracks back to Woodchopper where the first stop was the dredge. After filling the dredge tanks with diesel oil it went on to the camp where the various fuel tanks were filled. By this time, only sixteen crewmembers worked at the camp. This was a great reduction from the original 75 to 100 at the camp in the 1930s. Dale Patty, the company manager, took on the task of driving the CAT and Athey wagon to the Yukon hauling the nearly six tons of oil back to Woodchopper. According to Dale, "Everyone had to do many jobs. Hours were not important. I averaged 15 to 16 per day, 7 days a week." [107]

|

| Woodchopper dredge operating near the mouth of Mineral Creek (Dale and Karen Patty Collection, photo courtesy of Dale Patty). |

The dredge started production on June 2, 1958. Out of 142 days in the season, the dredge was in operation for 94.4% of the time during which it had processed 372,000 cubic yards of material. The last time the dredge operated (1953) it processed 381,000 yards. Prior to 1953, the average processed was 350,012 yards (Max = 413,191 Min = 199,500). The increased efficiency was due in part to re-setting the water jets in the screen, processing more material as it flowed through the dredge.

As with the Coal Creek dredge, the Woodchopper dredge was beginning to show its age. During the 1958 season, a weak point exposed itself in the screen drive. It broke three times until the crew finally re-engineered what turned out to be a manufacturing flaw. A little Alaskan ingenuity and a little extra welding solved the problem.

Another modification made to the dredge that saved a great deal of time, effort and money was to change the screen by using new plates that were 50% thicker than the original. The tumbling and grinding action of the gravel as it moved down the length of the screen wore the metal down rapidly. It was replaced, generally once a season, when it reached approximately 1/2" thickness. For the most part, this was required each year. By using the thicker material, the crew estimated that they could get two, if not three years use of it. This would save money in both materials and shipping charges in addition to the maintenance costs associated with down time installing new screen sections. [108]

For the first time since World War II, in 1958 Alluvial Golds Inc. and Gold Placers Inc. did not have a problem hiring or holding men to work on their crew. There was a recession going on in the rest of the country that was attributed in part to the success that mining companies in Alaska were having. The outlook for 1959 was equally bright. [109]

In the "General Statement of the Annual Operating Report," Dale Patty mentioned that a second bright spot for the season lay in rumors that the price of gold, which had been held at $35.00 an ounce for many years and might go up. If this happened, the company would have a number of productive years to look forward to. If not, the end seemed to be looming very large before them. [110]

On the low side, the final accounting for the year was not good. Even with a total output of $161,457.18, the bottom line for the season was in the red. This was due in part to a rapid decline in values beginning in September. During the first part of the season, they were running at about 50¢ a yard. In early September, they dropped precipitously to 36¢ a yard. Finally, with cold temperatures coming on hard and fast at the end of the season, the crew was forced to leave an estimated $3000.00 of gold frozen on the dredge until the following spring. [111]

The annual report to the Board of Directors, presented by company president, Ernest N. Patty describes how, although the bottom line for 1958 was in the red, the company should continue to operate in 1959. He explains that the extraordinary expenses associated with bringing the Woodchopper dredge back on line, and the additional maintenance costs to rehabilitate the Woodchopper camp after four years of virtual abandonment, would not be repeated the next season. In addition, the crew left the dredge in very good shape at the end of the season, which would equate to minimal work needed at the beginning of the next season. In his opinion, the company should continue to operate another year and evaluate their position again at the end of the season. This is the first time that any real discussion about the possibility of ceasing the operations at Coal Creek and Woodchopper appears in the company records. [112]

Figure 9.2: Comparison of Operating Expenses (1956-59) [113]

| Gold Placers Incorporated | Alluvial Gold Incorporated | |||

| 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 (Estimated) | |

| Dredge Repairs | $29,099.38 | $35,470.42 | $42,981.40 | $7,000.00 |

| Camp Maintenance | 2,439.99 | 2,234.13 | 10,964.82 | 8,000.00 |

| Shut-Down Expenses | 1,590.00 | 1,599.93 | 3,558.95 | 2,000.00 |

| Administrative Expenses | 40,623.35 [114] | 40,628.35 | 39,935.34 | 40,000.00 |

| Totals: | $73,52.72 | 79,932.83 | 97,440.51 | 57,000.00 |

Several factors were coming together having a profound influence on the company's future. First, the values of gold in the gravels ahead of the dredge were decreasing. Although some areas tested held higher values, to get the dredge to them meant cutting a path through either already dredged ground or that with very little gold. Second, with the price of gold still frozen by the Federal government it was harder and harder for the company to turn a profit, especially with marginal values. The company figured the break-even point for the operation was 35¢ per yard. If values dropped below that, they were simply throwing money out the back of the dredge. If they stayed above that, they could at least cover expenses, possibly making a profit. The decision on whether or not they could continue to operate hung precariously on what happened to the price of gold. [115]

THE 1959 DREDGING SEASON

In 1959, with operations back at Woodchopper, the crew got the camp and dredge up and running. Upon his arrival at Woodchopper, Dale Patty once again found labor problems. The company was already on their third waitress in the kitchen and the season was not even a month old. However, the new cook, Goldie Mortimer, whom Karen Patty describes as "a small and wiry worker," kept the crew amused with her constant malapropisms. When telling of a new shower cap she received from her daughter she described it as "It had two layers of plastic and was all filled with Seagram's." (It had sequins floating in liquid between the two layers of plastic.) [116]

Several years earlier, Ernest Patty commented that "No matter how skilled the management, they cannot put the gold in the ground." [117] The 1959 season brought with it a major downturn for Alluvial Golds Inc. and its sister company Gold Placers Inc. For the second year in a row, the companies operated at a loss. The primary reason for this was due to the gold recovery averaging nearly 20% less than the drilling estimates. Consequently, production figures for the season were only $124,874.00. Although this was not the lowest in the history of the two dredges (see Appendix D), when taking the greatly increased operating costs into account, it was truly a disappointing year.

The highlight of the year was entry of Alaska into the Union of States as the forty-ninth state. Even a remote mining camp nestled above the Yukon River got into the celebratory action on July 4.

Following breakfast, the whole camp was summoned to what has been labeled the "Woodchopper Flag Raising Ceremony." Everyone who could be spared was present -- Louise Paul with her five children and grandson, the Patty family with their three sons, Ted and Sally Murray, and an assortment of the worker crew. As Sally, with help from the Patty boys, hoisted the new forty-nine star flag to the top of the flagpole, Dale, ever mischievous behind his cool managerial demeanor, "tossed a large, economy sized firecracker to herald the new flag." As the explosion reverberated down the valley, Karen Patty later wrote that it was "Quite a site to see both the flag and poor Sally flying from the flagpole by the ropes." [118]

By the end of the 1959 season, Dale Patty realized that the era of gold mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek was fast coming to an end. Looking forward to completing work on his MBA from Stanford during the winter quarter of 1961, he decided that he wanted to move on to a different career path. At the annual Board of Directors' meeting, he announced his resignation from the company effective at the end of the 1960 season. He based his decision, in part, on the fact that the economics of mining gold on either of the two creeks had become nearly impossible. [119]

In his "President's Report to the Directors," Ernest Patty painted a gloomy picture at best. After stating that the company operated at a "serious operating loss" during the season, he elaborated that the values in the gravels averaged roughly 20% below the drilling test results. Therefore, the company's gross production was $60,800.00 below their normal expectations. He stressed that throughout the company's history, the drilling results and actual recovery were very close on the average. The 1959 season however was the exception to the rule. [120]

Although the ground that would be dredged during the 1960 season was adjacent to Mineral Creek, a rich tributary of Woodchopper, the fact that the undredged gravel lay next to some of the less valuable ground already dredged did not sit well with management. Patty stated that "The best assumption we can now make is that the area now stripped and ready for dredging next year will not be any better then the 1959 ground." [121]

Ernest Patty laid three alternatives before the Board of Directors:

First: Suspend operations indefinitely and wait for the price of gold to rise. This he stated was not something likely to happen within the next decade. The objections Patty saw to this course of action included the fact that the company would need to employ a watchman at the properties during the summer months to avoid theft and damage. They would need to do annual assessment work on the claims to maintain their validity. Shutdown costs would be in the neighborhood of $5000 to $7000 and would cover both camps. The company would also need to have someone on staff, willing to work without pay, to keep up with required government paperwork. Because the costs of getting the camps back into operation were bound to increase each year, Patty observed that unless the price of gold increased soon "the dredges will not produce again in our lifetime." [122]

Second: the company would run a salvage operation on Woodchopper Creek to use up the remaining supplies and already prepared ground ahead of the dredge. Patty notes that there would be minimal expenses to carry out such a plan, particularly since most of the fuels and lubricating oils necessary for running the operation were already on hand. There was also a fairly complete supply of spare parts for the dredge, including screen plates, wire rope, and diesel engine parts. The only expenses he foresaw, in addition to salaries for a reduced crew, were food and spare parts for the trucks and tractors as needed.

Dale Patty had agreed beforehand to take half a shift as winchman in addition to his duties, as had the dredgemaster. This would eliminate one winchman from the crew. Ted Murray, the long-time company accountant, agreed to work a night shift as an engineer. Because of the reduced crew size, they would not need a waitress to assist with mess duties, thus eliminating another person. Because the dredge would be operating in a salvage mode, it would not be necessary to have a fulltime welder on the crew. Patty suggested hiring one for the first month for any necessary repairs at the beginning of the season then laying him off for the remainder of the season. [123]

The one objection to this plan was that if the company failed to cover expenses, they would be in a more serious financial situation than they were at the end of 1959. In one of the few times Patty took a chance at predicting the odds of success, he wrote, "I feel that there is at least a 75% mathematical chance that the plan will succeed." [124]

Finally, Patty's third alternative: "Attempt to sell both operations at bargain prices." In this case, he cautioned the Board because he did not know where, or even if, a cash buyer could be found. The U.S. Smelting Refining and Mining Company based in Fairbanks [125] would not be interested as he had heard rumors that they too were in salvage mode for their properties. Over the previous several years, they had already idled several of their big dredges.

A second option under this plan would involve enticing new capital to invest in Alluvial Golds, Inc. and Gold Placers, Inc. but doing so would involve giving up control of the company to "outsiders." Patty states that "Rather than this I would prefer an outright sale at salvage prices."

Finally, he presented the idea that if they could sell the operations for $50,000 under this plan, and retain their investment portfolio, it would give the surest and most prompt return to the company's major stockholder Mrs. McRae. [126] He said that having "cash-in-hand would be better than the inherent risks of mining and future dividends." At last, the end was clearly in sight and everyone knew there was really no way to avoid the inevitable. [127]

When the 1959 season came to a close, the final accounting was not bright. The Woodchopper dredge recovered only $124,186.38 in gold for the entire season. This was down over 25% from the 1958 season. With returns like this, it was virtually impossible for the company to continue operations beyond the following season. [128]

THE 1960 DREDGING SEASON: AN ERA COMES TO AN

END

In describing the 1960 dredging season, Dale Patty had few comments other than labeling it "My worst year at the mine." If things could go wrong, they did during that season.

The ground the dredge operated in was marginal at best. The drill tests showed that it was barely worth dredging and the actual results were even lower. For the most part the values were at 40¢ or less per cubic yard. If they held, the company would make a minimal operating profit. If they fell, even slightly, they would operate at a loss for the third season in a row. [129]

Throughout the years, Ernest Patty had always talked about the possibilities of working Mineral Creek. It was one of the first creeks staked in the early 1900s and had all the appearances of being valuable ground. The only problem, the company had overlooked drilling beyond its mouth so they had nothing solid on which to base their conclusions. The values at the mouth however looked promising averaging almost 85¢ per yard. If the Board of Directors were to decide to continue working on Woodchopper, Patty recommended that they put in a small operation using a single CAT and a diesel shovel. The geology and terrain made it impossible to get the dredge very far up the creek. [130]

Because things looked worse than gloomy below the dredge toward the Yukon the company decided to turn the dredge around and move upstream for the mouth of Mineral Creek as quickly as possible. The company expected to see higher values in the gravels there. Finding this not the case, they turned again and headed downstream, digging only enough gravel to float the dredge. By the end of the season, they had reached roughly the same place it had been at the end of the 1958 season. [131]

The problem of holding on to the experienced crew continued to plague the camp. Midway through the season one of the winchmen quit. Dale did not attempt to replace him instead assuming the winchman's duties on top of managing the camp and hauling fuel oil. [132]