|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Golden Places The History of Alaska-Yukon Mining |

|

CHAPTER 14

Denali

Chronology: Denali

| 1889 | Frank Densmore prospected in area |

| 1896 | W.A. Dickey names Mount McKinley |

| 1898 | USGS confirms estimates of Mount McKinley's elevation |

| 1902 | USGS survey |

| 1903 | James Wickersham's report of gold prospects |

| 1904 | Joe Quigley and others prospect the country |

| 1905 | Kantishna Stampede |

| Eureka, Roosevelt, and Diamond founded | |

| 1910 | Slate Creek antimony |

| Sourdough Expedition to Mount McKinley | |

| 1915 | Silver-lead ore shipped; Mount Eielson lead-copper-zinc discovery; first antimony mined |

| 1923 | Alaska Railroad completion |

| 1923-31 | Joe Quigley ships silver-lead ore |

| 1924-65 | Crooked Creek placer operation |

| 1930 | Present park road completed |

| 1935 | Red Top mine worked |

| 1936 | Banjo mine worked |

| 1936-41 | Antimony mining at Stampede Creek |

| 1936-70 | Stampede Mine antimony output totals 3,700 tons |

| 1939-41 | Hydraulic mining on Caribou Creek |

| 1942 | Lode mine closed |

| 1947 | First ore shipments by airplane |

| 1950s-60s | Small Slate Creek revival |

| 1970s | Gold price increase sparks mining |

The Great Mountain

The best known and oldest park in Alaska was established as Mount McKinley National Park in 1917 and later expanded. The Alaska National Interest Lands Act of 1980 added more acreage and renamed the park Denali National Park and Preserve. Encompassing a huge area of the Alaska Range, it includes Mount McKinley at 20,300 feet, the tallest peak in North America, and its two lofty neighbors, Mount Foraker and Mount Hunter.

The Kantishna region, bordered on the south by the crest of the Alaska Range, on the north by the Tanana River, on the east by the Nenana River, and on the west by the lower Kantishna, produced most of the placer gold mined within park borders. But neither the Kantishna nor any other region of the present park attracted the early prospectors of the interior because the area was remote from established transportation routes. One prospecting party crossed from the Tanana River to the Kuskokwim River by way of Croschket and Lake Minchumina in 1889 but found no reason to linger. Frank Densmore, a member of the party, was among the first travelers to describe Mount McKinley in enthusiastic terms.

|

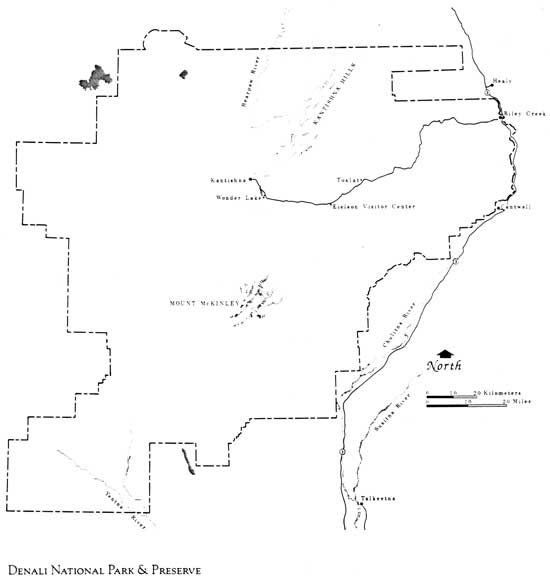

| Map 5. Denali National Park & Preserve. (click on image for a PDF version) |

It was not until 1896 when the great mountain was named by prospector W.A. Dickey. Dickey, seeing it from the Susitna River, estimated its elevation at 20,000 feet. George Eldridge and Robert Muldrow of the USGS confirmed Dickey's guess in 1898.

Once Fairbanks was founded in 1903 as a center for interior mining, prospectors were more willing to venture into the northern foothills of the Alaska Range. Miners based in Fairbanks were only some 150 miles distant from Kantishna, which was well within the range of their wandering.

Systematic exploration of the region began in 1902 with a USGS party led by Alfred Brooks. Brooks and six companions started from Cook Inlet, moved into the interior with a 20-horse pack train, and crossed the Alaska Range through Rainy Pass. Subsequently, the party traveled east along the Alaska Range. They were impressed by the numbers of mountain sheep and other game and cheered by the opportunity for the first exploration of the continent's highest mountain.

On August 1, Brooks made camp at the foot of a glacier flowing from Mount Foraker, which he named after Joseph S. Herron, the U.S. Army explorer, then described the grand mountain:

Two days later (August 3) we made our nearest camp to Mount McKinley . . . The next morning (August 4, 1902) dawned clear and bright. Climbing the bluff above camp, I overlooked part of the valley, spread before me like a broad amphitheater, its sides formed by the slopes of the mountain and its spurs. Here and there glistened in the sun the white surfaces of glaciers which found their way down from the peaks above. The great mountain rose 17,000 feet above our camp, apparently almost sheer from the flat valley floor. Its dome-shaped summit and upper slopes were white with snow, relieved here and there by black areas which marked cliffs too steep for the snow to lie upon. [1]

Kantishna Boom

Scenery, however grand, does not bring settlers into any area. They require a means of making a living. Several years passed before good news caused a rush to the Mount McKinley region. The Kantishna stampede of 1905 to a range of hills north of Mount McKinley opened a significant mining district. It had its origin in reports of gold finds made by Judge James Wickersham. Wickersham, after attempting to climb Mount McKinley in 1903, found promising signs after leaving the mountain and staked claims along Chitsia Creek in the northern Kantishna Hills. When he returned to Fairbanks, miners listened to his enthusiastic reports with interest. The following season Joseph Dalton and his partner, Reagan, prospected the basin of the Toklat River with success. Dalton and Stiles returned in 1905 to stake Friday and Eureka creeks. Joe Quigley and Jack Horn, acting on reports from trappers who spoke well of Glacier Creek, prospected there the same season to find paying quantities of gold. By this time Fairbanks was primed for a stampede. The Glacier Creek news inspired a number of miners from Fairbanks, who quickly staked virtually every creek in the region. Most arrived by boat up the Kantishna River and its tributaries or by dogsled after navigation closed in the fall.

Soon proud new towns—Glacier City on the Bearpaw River; Diamond on Moose Creek; and Roosevelt and Square Deal on the Kantishna River and Eureka Creek arose to provide services for the 3,000 rushers. Miners built scores of log cabins in each place, and enterprising entrepreneurs raised buildings for stores, saloons, and hotels. Some miners made good money working shallow paystreaks on Eureka and Glacier creeks, but pay dirt on other creeks—Friday, Glenn, Rainy, Moose, Caribou, Spruce, Stampede, Crooked and Little Moose—was soon exhausted. [2]

Wickersham appointed Lee Van Slyke the U.S. commissioner for the new mining district with headquarters at McKinley. By the time Van Slyke reached McKinley in September, the place had been deserted in favor of the new community of Roosevelt. Miners had relocated because " a good dry trail" extended 13 miles to the mines from Roosevelt, whereas from McKinley it was "a very wet one, a great deal of the way having to wade in water to your knees and waist." About 50 people were busy building at Roosevelt, so Van Slyke decided to stay "and find out all I can about the country." [3]

Just 10 months later things looked very discouraging. Van Slyke asked Wickersham for instructions, taking advantage of the opportunity to send his letter and get a return because a miner was preparing for a round trip to Fairbanks. "It looks as though I am up against it, although I hope not and I still have hopes for a camp here, but there are no prospectors in the field and so many have gone out this summer discouraged that I am afraid we will see no new recruits, and if not it means I will do no business." In the previous few months Van Slyke had only "done $202.95 worth of business and have trusted out $17.50 of that which I will probably never get." He was worried about his family in Washington state. His wife was ill, and he could not afford to stay in Kantishna without a better income. He would have to go Outside where he could earn a living. The only good news was from the discovery claim on Eureka where the miners found "one 43 oz. nugget and one 11 oz. the other day . . . it seems funny that all there seems to be is discovery and #1 on Eureka but it surely will be found in time yet." [4]

Hunter-naturalist Charles Sheldon visited the Kantishna district in summer 1906. He had voyaged from Fairbanks on the small steamboat, Dusty Diamond. The boat left Fairbanks in the evening, arriving at the mouth of the Kantishna River by the next afternoon. In the morning the boat pushed upriver on the sluggish, meandering Kantishna through low-lying, swampy country. From the Kantishna the boat voyaged up the Bearpaw Creek 3 miles to the site of the 1905 town of Bearpaw, now deserted. Returning to the Kantishna Dusty Diamond reached Roosevelt the next day,—"a row of about thirty cabins, including two stores, a saloon, and a sawmill—on the southeast bank of the Kantishna thirty miles above the mouth of the Bearpaw." The population of eight residents was preparing to abandon the place. From Roosevelt Sheldon and his guide, Harry Karstens, took a pack train to Eureka over a rough 30-mile trail. The journey involved three days of tough travel, "the horses constantly bogged and lost their packs." [5]

It was a relief to reach Eureka, "consisting of about twenty tents and a few cabins," on Moose Creek at the mouth of Eureka Creek, where the original gold discovery had been made. At the time Jack Dalton had 15 men working on the few hundred feet of rich ground he had claimed. The gold was reached at three to four feet, so digging was comparatively easy. The miners shoveled the gravel into a trough where it was washed, leaving the gold in riffles at the end of the trough. Dalton paid his miners $15 a day plus board. By summer's end he had exhausted his claims.

Sheldon was curious about the social life of miners at Eureka. He could understand that distance and remoteness prevented the maintenance of the usual saloon and gambling establishment, but suspected that these pleasures would be available in some form. "And sure enough," he observed,

it flourished in a large tent occupied by a single individual who, early in the summer, had left Fairbanks and penetrated this wilderness, to remain alone and absorb a large share of the miners' wages—the greater part of which in every mining camp in the northern country has fallen into the grasping hands of her kind.

After a day in Eureka, Sheldon and Karstens continued on up Moose Creek, enjoyed the view of Wonder Lake below them, then reached a good viewpoint of Mount McKinley. No other mountain he had seen, including those in the St. Elias Range—"one of the most glorious masses of mountain scenery in the world," compared to Mount McKinley.

Sheldon returned to Eureka to find that all but two or three miners had left for the winter. He commented favorably on the hardy miners who had carved out several communities the year before "with the mighty force and vigor of the pioneers of our race—the men who break the wilderness." Alaska's miners, Sheldon believed, faced difficulties unknown to pioneers on earlier frontiers: "He must face and conquer more serious conditions—those of a barren country, intense cold, long winter darkness, and still more, the danger of starvation and disease."

The district declined sharply after 1906. By winter of that year Roosevelt, Square Deal, and Diamond were deserted. Glacier survived with a few miners because it was near the creeks. Production was only about $15,000 in 1907 and the same in 1908. Future profits depended upon using heavy equipment. Large amounts of money and a freight road were needed but not forthcoming. Transport on the rivers and creeks in summer was uncertain because of low water conditions. Alfred Brooks of the USGS observed that "for the present the outlook for mining does not seem hopeful." Although a recording office was established at Eureka in 1909, it did not seem necessary. Production that year was only $5,000; in 1910 it was $10,000. [6]

In 1911 only 20 miners were working in the district on Glenn, Bearpaw, Eureka, and Moose creeks. Gold production between 1910-1919 was between $15,000 and $30,000 each year. All the mining was open-cut ground sluicing when water levels were highest.

The Sourdough Expedition

What made the 1910 season famous was one of the most celebrated sabbatical ventures in the history of mining. It came about through discussions among Kantishna miners wintering in Fairbanks in 1909-10, enjoying the amenities of Bill McPhee's saloon. As workers in the awesome shadow of Mount McKinley, they took more than a passing interest in the alleged climb of the mountain by Doctor Frederick Cook, then being denounced for claiming to have reached the North Pole. The Explorers Club of New York determined that the mountain record had also been faked. Herschel Parker and Belmore Browne, members with Cook of the 1906 expedition, had abandoned the mountain's ascent near season's end, then Cook returned with one packer to claim a successful ascent. Cook's book about the climb appeared in 1908. His packer confessed to the fraud in fall 1909 amid the North Pole clamor.

Mining prospects did not look too bright for the 1910 season, so the boys decided to show what Kantishna miners could do. Doc Cook was a fake, but they were not, and the great mountain should be conquered by sterling local men. Bill McPhee provided $500 for expedition expenses. It was not enough money for fancy mountaineering equipment, but the Sourdough Expedition, as they were called, did not need such stuff.

They decided that the Muldrow Glacier was the best approach and struggled upward for days, hacking steps and bridging crevasses. At the head of the glacier (11,000 feet), Tom Floyd quit. Pete Anderson, Bill Taylor, and Charles McGonagall struggled on. McGonagall quit on April 10, after a storm's fury delayed their ascent. The others kept on to the summit, dragging a 14-foot spruce pole which they erected to fly an American flag. They hoped that friends in Fairbanks would be able to see the flag, but Fairbanks, of course, was not that close.

After their feat the miners went back to work. They were not literary men and did not try to capitalize on their record by placing magazine articles or giving lectures. Folks in Fairbanks knew, and that was enough for them. Some folks in Fairbanks doubted their success until Archdeacon Hudson Stuck climbed the higher south summit in 1913 and saw the sourdough's flag on the north summit.

Conditions in 1916

In 1916 Stephen Capps of the USGS investigated the Kantishna region to report on the current mining and future prospects. He marveled at the paucity of people in the area. During a two-week period he encountered only two hunters before "moving up to the mines—if they can be so dignified." Reaching the mines on July 31, he talked to a handful of men and remarked their woes: "The men on this creek are so isolated that they had heard no news from outside since April." Capps respected the miners who were willing to work under such difficult conditions. Costs were high because of area's remoteness, and "even the mail arrives at very irregular intervals, for no mail route to the mining district has been established and mail is brought in only by courtesy of the chance traveler. Often the camp is isolated from communication with the outside world for weeks or months at a stretch." [7] Among the railroad's benefits already achieved by 1916 was the establishment of a new supply point for the region's miners. The Indian mission town of Nenana at the Nenana River's entry to the Tanana River gained prominence when selected that year as a station and transfer point for rail freight. Shipping freight to the diggings via Nenana cut 55 miles from the winter sled road supply route to the diggings.

As Capps observed in 1916 all of Kantishna's placer mining had been with open-cut methods. Miners utilized ground sluices to remove the gravel within a foot of bedrock, then, working more carefully, shoveled the remaining gravel and bedrock into the sluice boxes by hand. Most sluicing was done in the early spring to take advantage of the greatest streamflow, although miners who built dams could store water for use in the later low-water season. The obvious weakness of the system was in its general dependence on streamflow and, as elevations ran from 1,600-3,000 feet, the flowing season only extended from May to September. Miners could not always count on a four-month season because smaller streams diminished in late summer and could not provide sufficient water for sluicing. Depending upon particular local conditions, the mining season lasted from 100 to 120 days.

Miners working for wages earned $6 daily and board for a 10-hour day or $1 an hour without board, but there were few wage laborers in the district. Men who did not own stakes in claims did not hang around the area waiting for employment. And with better opportunities in less remote districts, it was hard for owners to encourage laborers to come in for such a short working season.

After the boom of the first few years, the district could not support even a small store. A miner who miscalculated his food or equipment needs had to borrow from others or go without. Thus, although the district with its pick-and-shovel methods could be described as a poor man's one, it was not. Miners had to look ahead and invest many months in advance of any possible return. Since 1906 the district's population had stabilized at 30 to 50 persons.

Though most of the high mining costs could be attributed to Kantishna's distance from supply points, there were detrimental local conditions as well. High elevation provided easier access than was found in many low-lying mining areas, but altitude also meant that wood for fuel and mining needs was not nearby. Virtually all the placer ground lay above timberline, so wood had to be hauled from a distance of 1 to 8 miles, depending upon the particular creek being worked. In early days miners enjoyed the benefits of a sawmill, but after the decline they had to cut timber by whipsaw.

An experienced Alaska geologist like Capps could observe and understand the elements of mining technology and logistics in a district after he looked things over and talked to miners. With his experience, the knowledge gained from field interviews, and the accumulated experience of Alfred Brooks and other geologists, Capps' published report was likely to be accepted by working miners and other interested individuals as the latest and most authoritative word on the subject. On the scientific level, however, Capps could not depend much on others. He was often the only professional geologist to see a particular mining region. It was his joy and responsibility to answer the ultimate questions: Where did the precious minerals originate and how did they reach this place?

In Kantishna Capps had no trouble seeing that the underlying rock was the Birch Creek schist, "cut by relatively small bodies of intrusive rocks" of various ages. The younger rocks included "some dikes and stocks of granite porphyry and quartz porphyry that may be genetically related to the mineralized quartz veins. The schists are in places likely siliceous and include beds of quartzite schist." Throughout the schist numerous quartz veins are distributed among the rock mass, and some contain visible free gold. Mortar tests of some veins revealed that native gold was widely distributed. Since the largest, most continuous gold-bearing quartz veins were in the basins of placer-rich streams, there was conclusive proof that most of the gold derived from "the erosion of the larger quartz veins that cut the schists." [8]

Capps, like the prospectors who had led the way, was impressed by the visible evidence found in gold nuggets. Observing those gathered in a miner's cleanup he found them "rough and angular," indicating that they had traveled no great distance from the outcrop of the vein of origin. Gold taken farther downstream tended to be finer and more smoothly worn because it had been transported a greater distance. [9]

Capps' observation confirmed those of the miners who had located their ground by making the same observations. The geologist's farther and more scholarly contributions here were only useful for relating the origin of the gold to ancient ice age activity—matters that interested practical miners only to the extent that the knowledge helped their eyes discern similar geological conditions. Miners studied Capps' words even when he entered the theoretical realm:

To just what extent the gold-producing steams were once occupied by glaciers and their preglacial placer deposits removed by ice erosion has not been definitely determined, for the glacier evidence are inconspicuous and poorly preserved. It can be stated, however, that in those portions that were glaciated the erosion of the ice was sufficiently severe to disturb or remove the greater part of the preexisting gold placer deposits, so that any concentrated deposits of gold that are now present are due to the erosion of streams since the ice retreated. Below the edges of the glaciers stream erosion was retarded during the ice advance, for the waters were burdened with an unusually large supply of rock waste, and this they deposited as outwash gravels beyond the ice edge. The streams assorted the materials of the outwash gravels to some extent, but much less than is common in normal, lightly loaded streams.

With the final shrinkage and disappearance of the glaciers from this district the steams commenced their task of readjusting their valleys to conditions of normal erosion. Less heavily loaded than when they were receiving glacial waters, they began to intrench themselves in the deposits of outwash gravels, which now appear as high benches or terraces along the lower streams, especially those on the north side of the Kantishna Hills. In cutting down through these gravels the streams in places occupied somewhat different courses from those along which they had formerly flowed, and canyons show the position of obstructions encountered in the downward cutting. [10]

Keen to report his findings scientifically and to help miners, the geologist sometimes had to deride local theories. Overturning local legend and prejudice did not make a geologist popular, and such disagreement explains some of the ambivalence in miners' attitudes toward USGS men. Kantishna miners believed that gravel taken from a prospect shaft on Glacier Creek resembled the "white channel" gravels of the Klondike. Yet panning these gravels did not confirm hopes of richness. Capps determined that the Glacier Creek gravel was, despite appearances, dissimilar to that in the Klondike. It was probably of an earlier Tertiary age and had been affected by erosion and glaciation in very different ways. The misconception of the miners, like their optimism, was intriguing but gave way before the relentlessness of scientific inquiry. In the long run miners would rather have the help of science than muddle along without it.

The total yield of Kantishna's gold from 1905-1916 was below a half million dollars. With only 35 miners in the entire Kantishna district in 1916, prospects for development were hardly blooming. Yet Capps was not ready to dismiss the region. One foundation for his optimism—ardently shared by others in Alaska—lay in completion of the Alaska Railroad from tidewater at Seward to Fairbanks. The railroad had triggered Capps' expedition, as it seemed likely that its completion in 1923 would end the district's isolation and high mining costs.

Mining areas were off line, but Capps believed that feeder roads would undoubtedly be built. Coarse gold had been discovered in many creeks, including Rainy, Spruce, Myrtle, Moonlight, Stampede, Crooked, and Flume. Railroad survey party members had undertaken a little panning themselves, finding 10- to 30-cent nuggets on three streams that miners had not yet worked. Another prop to Capps' carefully expressed hopefulness was his appreciation of the limitation of the previous decade's mining. Miners had not yet utilized hydraulic or mechanical methods. Their pick-and-shovel work had taken the easy rocks of a few creeks, leaving deeper and less profitable ground unworked. Since other regions reworked by dredges had proved profitable. there was reason for optimism regarding Kantishna.

Creation of Mount McKinley National Park

In 1917 Congress set aside 2,200 square miles of land south and east of the Kantishna mining district as Mount McKinley National Park. Even though the purpose of the park was the protection of the mountain environment and wildlife, the rights of miners holding claims within the park were acknowledged. Kantishna miners perceived some economic value to them in the park's creation. Roads would be built that they could utilize for hauling supplies and ore.

The negative aspect of the park's creation soon became a matter of controversy between miners and Chief Ranger Harry P. Karstens (later named superintendent). Miners had been long accustomed to killing game for food and had a hard time adjusting to hunting restrictions. Aside from that, however, miners remained free to prospect and mine within the park.

Karstens was a logical choice to head the park. He knew the region intimately and had guided Charles Sheldon in 1900, 1907, and 1908. Sheldon, a renowned naturalist and big-game hunter, had been an influential lobbyist for the park's establishment. Karstens had also climbed the south peak—the highest point of Mount McKinley—in 1913. Credit for this climb was usually given to the Rev. Hudson Stuck, who organized the party, but Stuck himself admitted that the party would not have succeeded without Karsten's leadership. Walter Harper was the third member of the summit party.

Karstens had rushed to Dawson over the Chilkoot Pass in 1897. In spring '98 he and other miners staked claims 100 miles below Dawson within Alaska and laid out the Eagle townsite. After mining for a time on Seventymile River, Karstens became a contract mail carrier. He and Charles McGonagall carried the first mail from Fairbanks to Fort Gibbon and handled the bimonthly route between Fort Gibbon and Gulkana on the Copper River. Karstens also guided Billy Mitchell, when the army officer surveyed the route for the telegraph from Eagle to Valdez in 1901-1902. Karstens was among the original Kantishna stampeders in 1905. Subsequently, he carried mail from Fairbanks to the Kantishna.

Placer Mining 1920-40s

The USGS estimated that only $480,000 in placer gold was taken from Kantishna from 1905 through 1921. The forecast improved when hydraulic operations were introduced in 1920 on Moore, Glacier, and Caribou creeks. One company built a ditch and flume from Wonder Lake to Moose Creek; and others drew water from the various streams. Contrary to all expectations the two large hydraulic operations did not reverse the dismal pattern of meager production. In 1923 production for the district from the efforts of 19 miners was only $13,000. Both hydraulic operations were shut down by 1928. Mining by hand methods during the depression years did not bring in much money.

A resurgence occurred in the mid-1930s when the gold price rose and with the completion of the road through McKinley National Park from the railroad to Kantishna in 1937. A third stimulant was in the development of lode mining, which made all mining in the region appear in a more promising light.

In 1939 the Caribou Mines Company and the Carrington Company utilized yard-bucket draglines on Caribou and Glacier creeks to good effect. All previous records were broken in 1940 when the district produced 4,000 ounces of placer gold worth $139,000.

This brief "golden age" occurred in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Placer mining was curtailed during the war, and its resumption after the war did not profit most miners. Attempts to establish dragline operations and gain some of the success of pre-war years were not successful. Only one or two small placer outfits worked in the 1950s and '60s. In the mid-'70s to mid-'80s period, gold mining operations took a profitable turn. The gold production total of 55,000 ounces reported by Budtzen in 1978 reached 80,000 ounces by 1986 and good future prospects were reported. [11]

Lode Mining

The first lode mining in 1905 was of antimony rather than gold. Joe Quigley shipped 12 tons of stiblite ore from the Last Chance mine on Caribou Creek, taking advantage of high prices offered during the Russo-Japanese war. Quigley also found gold, silver, and other mineral veins along Mineral Ridge, later renamed Quigley Ridge. Other prospectors, including Tom Floyd, made discoveries in the Glenn Creek area from 1907-09.

From 1919-24 properties on Quigley Ridge and Alpha Ridge that Quigley leased to Tom P. Aitken and Hank Sterling produced 1,435 tons of ore. The yield of $300,000 in silver, gold, lead, and zinc stirred fresh interest in the Kantishna, making it easier for prospectors to raise grubstake money.

The renewed prospects of the Kantishna district excited some Alaska journalists. The district is "one of the richest in the U.S.," alleged R.C. Morris in the Pathfinder: "The sum is about to shine on men like Jack Hamilton, Joe Quigley and Billy Taylor who held claims for 17 years existing on sow-belly and beans." After 1924 the sun did not continue to shine on Quigley and Alpha ridges. Once the high-grade ore was exhausted, further production was inhibited by high transport costs. [12]

Transportation problems had always inhibited placer-mining, but the situation was far more difficult in lode mining. The silver ores from the Eureka area were sacked and hauled over the winter trail to Glacier City, then by horse-drawn sledge 22 miles to Roosevelt. With the opening of navigation a steamboat barged the ores down the Kantishna to the Tanana then down the Yukon to St. Michael and ocean transport. By the time the ores reached the Tacoma smelter, transport charges totaled $75 a ton. Only the richest ores could be shipped profitably. These were gone by 1924, and lode production ended in the southern part of the district. Geologist Thomas K. Bundtzen, the leading Kantishna historian, observed that silver would have to assay at 100 ounces a ton before this venture could profit. "Silver was worth nearly $1 an ounce in 1920. Lower-grade ores today remain on the dumps." [13]

During the same summer of 1921 that the mineral production on Quigley and Alpah ridges made stirring news, Joe Quigley made another strike. This time it was reported that he found a vein of gold, silver, and lead which "caused a small stampede from other Kantishna sections to Copper Mountain." In fact the Copper Mountain vein was mainly lead, copper, and zinc; and it did not profit Quigley or stampeders to Copper Mountain. The Guggenheim mining interest did acquire leases from claim holders, but the vein did not prove rich enough for ore production. [14]

Copper Mountain was in the news again in 1924 when bush pilot Carl Ben Eielson landed a World War I Jenny on a gravel bar. The gravel-bar landing was much publicized because it showed the potential of light aircraft in Alaska. Five years later Eielson died in a plane crash, and Copper Mountain was renamed Mount Eielson.

The scarcity of zinc during World War II brought attention to Mount Eielson in 1943. A USGS survey indicated that zinc-lead deposits on its north slope might total 100,000 tons yielding five percent zinc and three percent lead. The USGS report, published in 1944, did not arouse commercial interest in mining Mount Eielson.

Floyd R. Marsh

A persistent prospector still could have some luck even after the country had been pretty well prospected. Floyd R. Marsh was trapping out of Nenana in 1920 when he decided to seek gold at Kantishna. His knowledge of minerals and mining did not run deep but he had confidence in himself. In late May he and five other miners made a three-day voyage from Nenana to Kantishna on a small sternwheel steamer.

From the landing they hiked some 30 miles to the diggings on Moose Creek. Miners were working with shovel and sluice boxes on Moose, Eureka, and Eldorado creeks, but Commissioner Herbert Wilson urged Marsh to try Yellow Creek, 8 miles distant. [16]

On his first day on Yellow Creek, Marsh panned about $100 and subsequently found a few other "hot spots" overlooked by miners earlier. Soon Marsh exhausted the small pockets. As food prices were too high for his resources—flour and sugar cost 50 cents a pound—Marsh lived on beans and groundhogs until scurvy felled him. Neighbors helped him through his illness, and Marsh went back to work. Eventually he found a quartz vein on the side of a mountain 300 feet above Yellow Creek.

Everyone was excited about the discovery, which seemed to promise long-range lode potential for the area. Marsh hiked out 80 miles to the railroad and Nenana, resolving to earn enough money for an all-out mining effort the following year. His fame had preceded him to Nenana, where his gold discovery was heralded. Entraining to Fairbanks he got his quartz assayed. It was said to be worth $500 a ton!

Marsh worked through the winter and summer, then mushed back to Yellow Creek in the fall. For some weeks he drove a tunnel and hauled out 25 tons of ore before the vein ran out. Johnnie Lake, who had a small stamp mill on Moose Creek, paid $8,000 for the ore and the claim, and Marsh returned to Nenana in December 1921.

Marsh's story of good luck was unusual. More commonly, inexperienced men fared poorly. There were several other lode discoveries in the 1920s and 1930s. Joe Quigley made a major lode find in 1931 after tunneling into his Banjo claim on Iron Gulch. The large quartz-sulfide vein yielded $15 to $18 of gold per ton.

Technical Help

Prospectors in Alaska got some help from the University of Alaska, founded in 1922 as the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines. The college, while struggling for its existence in early years, provided short courses in mining technology taught by Earl Pilgrim and geology taught by Ernest N. Patty. Patty, who later supervised dredging on Coal Creek in Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, utilized the active mining operations in the region for instruction, taking students into mines at Ester Dome. They rode down a mining shaft in a hoisting bucket to examine the drift mining 30 to 100 feet below the ground. Miners thawed the frozen ground with hand-driven steam points, following the paystreak at bedrock by slow digging. "This drift mining in low tunnels," Patty said, "was the most killing work I had ever seen." [17]

Both Patty and Pilgrim advised miners at Kantishna. By the 1920s aircraft had made getting to the mines much easier. Pilots sometimes landed on Wonder Lake's ice in preference to the rough-cut airstrip. From Wonder Lake there was a trail to Moose Creek, then on to the Quigley mine. On his first visit Patty met a living legend, Fannie Quigley, who provided good food and local gossip for countless visitors over many years.

In 1933 A.D. McRae, anticipating the increase in the gold price, hired Ernest Patty to help find properties of potential value. With mining geologist Ira B. Joralemon the men looked over the famous old Cliff mine near Valdez. The Cliff mine had produced a million dollars in quartz from a vein that extended 365 feet below ground and under the sea bottom. Mining stopped when blasting under the sea flooded the works. McRae spent two months trying to pump the mine dry, then abandoned the effort.

After this failure McRae tried to mine at Nuka Bay on the Alaska Peninsula. Miners reopened an abandoned mine and drove a 200-foot tunnel. Once again the effort failed to benefit the owner. Patty then recommended the Quigley properties at Kantishna. The Quigleys sold to McRae, who spent $40,000 on 1,000 feet of underground work. Including the purchase price, McRae expended a total of $70,000 but did not find any marketable ore, so he closed down after a season.

Antimony

The Kantishna district's Stampede Creek area developed as the major antimony-producing region in Alaska. Antimony (or stibium) is a silvery-white, brittle, metallic chemical element of crystalline structure, found only in combination and chiefly useful in alloys with other metals to harden them and increase their resistance to chemical action. One of antimony's uses is in combination with lead in the manufacture of storage batteries. Another big use was to make fireproof paint.

Large reserves were rare in Alaska as everywhere else. Antimony occurs as high or low grade in veins, in lenses, and in veinlets in shear zones related to the Stampede fault. Low grade ranges from 10 to 20 percent antimony, and high grade exceeds 50 percent. Antimony had been produced on the Seward Peninsula and near Fairbanks but had been ignored in more remote districts. No one knows when antimony was first discovered in Alaska, but the first mining was in 1915 in response to price jumps during the war. As early as February 1908 James Wickersham sent two ore samples taken by a prospector with whom he was associated to W.R. Rust of the Tacoma Smelter. "These pieces," Wickersham wrote, "are from heavy veins in the vicinity of supposedly very rich antimony bodies." The miner had already secured an assay from a New York concern that indicated an antimony content of 56-1/2 percent. The vein was large but transportation difficulties were immense, so the miner was continuing his search for other deposits. Rust did not find enough value in the ore samples to encourage mining. "If the mine would produce antimony running from thirty to forty percent, it would pay to ship it east to antimony smelters, but this is too low grade." [18]

Wickersham planned a trip to Kantishna in 1908 to investigate his gold placer properties but also intended to bring out more antimony ore samples to send to Rust. Rust's smelter charged nothing for doing the assays. "We are glad," Rust told Wickersham, "to contribute this much to the development of the country and hope to get our money back by ore shipments should the mines amount to anything." Rust did not get much, if any, Kantishna ore before he sold the smelter to the Alaska Syndicate which was at the time developing the Copper River copper mines. [19]

Wickersham, Bill Taylor, and others had interests in several gold claims. It is not apparent that the judge made any money out of Kantishna from 1905-1908, and in September 1908 he was forced to tell Taylor to avoid hiring help or otherwise contracting debts: "Some of the people interested with us have a bad case of cold feet, and refuse to raise more money at this time for prospecting." Taylor would have to "pay as you go or don't go." There were enough supplies on hand for Taylor and the Quigleys to do some prospecting and the current year's assessment work. [20]

Wickersham's partners included the Quigleys, Joe and Fannie, who gained a fame of sorts as long-time Kantishna residents. Joe Quigley crossed the Chilkoot Pass originally in 1891 and prospected throughout Alaska and the Yukon. At Kantishna he teamed in marriage with Fannie who operated a tent restaurant. Over the years the Quigleys because famous for their hospitality as well as unrelenting prospecting and mining. Fannie, an excellent hunter, cook, and baker, always had something on the stove for hungry visitors.

Tom Floyd and others developed antimony deposits on Slate Creek, producing 125 tons of high-grade ore in 1916. Some developmental work was also done at Stampede that year and in 1926, but sustained work awaited Earl Pilgrim's arrival in 1936. He was attracted by a 26-foot wide vein of nearly pure stibnite, a find that had been known since the original Kantishna rush but awaited favorable economic conditions for exploitation.

In 1921 a geologist estimated a possible 70 tons of high grade at Stampede Creek. [21] Earl R. Pilgrim required considerable persistence to transport the antimony ore from Stampede. Beginning in 1936, for 10 years he hauled the ore 50 miles to the Alaska Railroad by tractor and sled, taking 40 tons on each trip. Transport could only be undertaken during the coldest months because the haulers required a firm frozen surface over the land and five river crossings. Things would have been much easier with a road tie-in. The mine was only 21 miles from the McKinley road, but neither the Alaska Road Commission nor the park service favored the road he wanted.

In 1947, at a cost of $25,000, Pilgrim constructed an airfield and a 2-mile road to the mine. Air freight rates were high, so he could only mine during the years that antimony prices were high. He paid $30 a ton in 1951 to fly ore to Nenana, then $20 a ton for the rail and sea transport to Seattle or Portland. The final destination, whether California, Indiana, or overseas would determine what further rail or maritime freight charges would be. [22] When Pilgrim was offered from $6.00 to $7.50 for 20 pounds, he could stand the freight rates, but when the price dropped to $4.00, as it did in 1952, he did not mine. In 1960 $250,000 was appropriated for a road to Stampede, but for lack of further funding the first year's construction was not followed up.

Recent Mining

Antimony commanded high prices during the years 1970-72, and shipments from Slate Creek, Last Chance Creek, and Stampede rose.

Increases in gold prices in the 1970s caused a revival in placer mining by individual miners. Much of the work was done with bulldozers and front-end loaders on old, previous mined gravels.

Interest in lode deposits accelerated, too, with high gold and silver prices. At the Red Top Mine a 35-ton-a-day flotation mill was installed. That season the first 100 tons of ore were shipped outside to a smelter. Unfortunately, results did not justify further work.

The Kantishna chapter of Alaska's mining history has special interest. As a gold-mining district it ranked in 27th place among Alaska's districts. A summary of total mineral production follows:

| Gold: | 99,307 ounces |

| Silver: | 308,716 ounces |

| Antimony: | 4.75 million pounds |

| Lead and zinc: | 1.5 million pounds |

Antimony production established Kantishna as the richest section of the state for that mineral. Overall 44 percent of Alaska's total output of antimony came from Kantishna. The area's mining include diversity of yield, considerable lead and zinc production, and the unusual balance between placer and lode mining. Lode mining was not prominent in the Yukon basin, but in the late 1930s the Red Top Mine ranked fourth among 20 Yukon lodes. The location of mining areas has also contributed to its interest. Mount McKinley is the best known geographic feature of Alaska and a much-visited place. Finally, the region gained interest from associations with mountain climbing and early big game hunting expeditions and, most particularly, because of James Wickersham's activities there. As the interior's first judge and long-term territorial delegate, Wickersham has been long the best-known Alaska historical figure.

A study published by the Bureau of Mines in 1986 confirms earlier reports of large gold reserves in the Kantishna district. In 1983 it was estimated that there were 688,000 ounces of recoverable gold, of which 288,000 ounces are covered by existing claims. "At 1983 mining rates," the Bureau of Mines asserts, "approximately 35 years would be required to process the indicated reserves on existing claims." [23]

Other Mining Areas in the Denali Region: Yentna

The Yentna district includes the area drained by the western tributaries of the Susitna River between Alexander and Sunshine creeks and by its eastern tributaries between Sunshine and Talkeetna. It first attracted miners in 1905, mostly from places on Cook Inlet. An early newspaper account said that "Eleven men have been working all summer on Hahiltna Creek and taking out an average $10 a day in coarse gold. Seven of them came down the other day to the trading posts on the inlet to get outfits for the winter." The original strike had been made in November 1904, according to the Seward Gateway, but the secret was kept for almost a year. Among the discoverers was R.C. Richardson, a Klondike veteran, who was made deputy recorder for the district. [24]

By late September a stream of miners from Sunrise, Hope, and Seward were going to Yentna. The location, according to the Gateway, was "100 miles above Susitna Station which is 20 miles from the mouth of the Susitna River." Stampeders were using boats, and there was a small freighting operation on the Susitna.

When the first stampeders did not return in late fall or early winter, others on Cook Inlet were encouraged to try the Yentna. In February the Gateway predicted "a big rush" before breakup. By May roadhouses had been established along the trail. In August Seward's Chamber of Commerce asked the U.S. War Department to build a railroad from Seward to Nome "branching from the main line of the Alaska Central Railroad and the Susitna valley and extending northwesterly through the Yentna valley." [25]

Yentna miners used the Tokositna River as a route to the Chulitna and Susitna rivers to Cook Inlet. By the late 1920s the placers had been worked out. Among Alaska's gold placer districts the Yentna ranked seventeenth until 1930 with production of $2,443,500. In the 1970s and 1980s mining revived in the region just as with the Kantishna Placer region.

Valdez Creek

The river called Susitna ("Sandy") by the Tanaina Indians flows southwest 260 miles from the Susitna Glacier to the head of Cook Inlet. In 1903 a strike was reported on the upper river which attracted a party of five men who set out from Valdez in February. The miners found gold on Galina Creek, which they renamed Valdez Creek, and took out 100 ounces of gold in only two weeks before returning to Valdez. In 1904 some 150 miners worked the creek. By 1909 miners had taken $300,000 from Valdez Creek. Subsequently, production dropped off, and few miners remained. Total production for the district by 1930 was $475,700, ranking it 30th among placer districts in Alaska.

Valdez Creek, a tributary of the Susitna River, is far from the port town of Valdez but was best reached from Valdez. The area was cut off from Cook Inlet and the lower Susitna River by Devils Canyon. Travelers in the Copper River basin, however, could cross easy grades to the upper Susitna and Valdez Creek. The first mines used the Valdez Glacier route or the Valdez Trail, and soon established a well-used trail between the upper Copper and upper Susitna rivers.

In 1904 an Indian guide showed the Gulkana Trail to Valdez Creek miners who were leaving the diggings at season's end. Subsequently, the Valdez Glacier route was abandoned and a freighter offered winter shipping at 30 cents a pound. It was 250 miles from Valdez to Valdez Creek via the Valdez Trail, the west fork of the Gulkana, and across a low divide to Maclaren River and Valdez Creek. From Gulkana most of the travel was over river ice. Except in very special circumstances freight was not shipped in during summer as the rate soared to more than three times the winter cost. [26]

Recent production on Valdez Creek has been very high. Some 50,000 ounces of gold was mined in 1988, making the mine have the "largest onshore placer mine in the entire state and perhaps in North America." [27]

Chulitna

After the success of mining on Valdez Creek prospectors looked hard at other parts of the upper Susitna. Some placer claims were located in 1907 on Bryn Mawr Creek, a tributary of the West Fork of the Chulitna River. Lode claims were made nearby in 1905 (the Golden Zone) and others from 1911-1915. During this period the Dunkle coal deposit on Costello Creek was discovered, and some coal was produced for local use.

When gold prices went up in 1934, interest in the Golden Zone mine—the original lode discovery—was aroused. Work from 1936-42 opened 1,900 feet of underground workings. In 1941-42 some 869 tons of ore were mined, yielding 1,581 ounces of gold, 8,617 ounces of silver, 21 tons of copper, and 3,000 pounds of lead. Some 5,000 tons of coal was shipped from the Dunkle Mine. Gold mining was not resumed after the World War II closure, but 59,000 tons of coal were shipped from the Dunkle Mine from 1952-54.86

Prospects look good for the future. In 1988 the Bureau of Land Management made a significant discovery on an Ohio Creek tributary lying just outside park boundaries.

Notes: Chapter 14

1. Quoted in Grant Pearson, History of Mount McKinley National Park (Mount McKinley: National Park Service, 1953), 20.

2. Thomas Bundtzen, "A History of Mining in the Kantishna Hills," (Alaska Journal, Spring, 1978), 151.

3. Van Slyke to Wickersham, September 11, 1905, Wickersham Collection, AHL.

4. Van Slyke to Wickersham, July 16, 1906, Wickersham Collection, ASL.

5. Charles Sheldon, Wilderness of Denali (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1960), 6-8, 88, for this and following quotes.

6. Alfred H. Brooks, Mineral Resources of Alaska, 1907, USGS Bulletin No. 345, (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1908), 45; Rolfe Buzzell, "Overview of Kantishna Mining History," (NPS files), 3.

7. Capps to wife, June 25, 1916 (starting date of letter encompassing a June-August diary of activities), Capp Collection, UAF; Stephen Capps, "Kantishna Region," in Alfred H. Brooks, Mineral Resources of Alaska 1916, USGS Bulletin No. 662, (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1918), 283.

8. Capps, "Kantishna," in Brooks, Mineral Resources of Alaska 1916, 295.

11. Buzzell, Overview, 7-11, 13-16, 18-20; Budtzen, "A History of Mining in the Kantishna Hills," 160; Steven A. Fechner and Robert B. Hoekzema, "Distribution, Analysis, and Reccovery of Gold from Kantishna Placers, Alaska," Report 11-86, Bureau of Mines, 1986) 5; Tom Bundtzen to author, July 20, 1989.

12. R.C. Morris, "The Kantishna Mining District," (Pathfinder, June 1921), 6.

13. Bundtzen, "A History of Mining in the Kantishna Hills," 156.

14. "Kantishna," The Pathfinder, (September 1921), 6.

15. News Release, Dept. of the Interior, June 15, 1944, NPS files.

16. Floyd R. Marsh, 20 Years a Soldier of Fortune (Portland: Binfords and Mort, 1976), 32.

17. Ernest H. Patty, North Country Challenge (New York: David McKay & Co., 1969), 32.

18. White, "Antimony Deposits," 331.

19. Wickersham to Rust, February 6, 1908 ASL; Rust to Wickersham, March 4, 1908, Wickersham Collection, ASL.

20. Wickersham to Rust, April 2, 1908; Rust to Wickersham, May 11, 1908, Wickersham Collection, ASL.

21. Wickersham to R.W. Taylor, September 12, 1908, Wickersham Collection, ASL.

22. Fairbanks News-Miner, May 27, 1952.

23. Steven A. Fechner and Robert B. Hoekzema, "Distribution, Analysis, and Recovery of Gold from Kantishna Placers, Alaska", 3.

24. Seward Gateway, August 26, 1905.

25. Ibid., May 19 and August 1, 1906.

26. Terrence Cole, "History of the Use of the Upper Susitna River," (Anchorage: Dept. of Natural Resources, 1979) 1-12.

27. Statement from James Halloran, Mining Evaluation Div., NPS, ARO, June 1989.

28. Harlan D. Unrau, "Historical Overview, Draft Mining EIS," (October, 1986, NPS files).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

golden_places/chap14.htm

Last Updated: 01-Oct-2008