|

PECOS

From Folsom to Fogelson: The Cultural Resources Inventory Survey of Pecos National Historical Park |

|

CHAPTER 2:

Previous Archeological Work

Susan Eininger

The written history of Pecos Pueblo is a long one by Southwest standards. For more than 400 years, its topographic setting, visual prominence, and cultural diversity have been of interest to both the casual and purposeful visitor in the Upper Pecos Valley. Early Spanish explorers and missionaries (Bandelier 1881; Hull 1916; Schroeder and Matson 1965; Winship 1896), and later military personnel and westward travelers (Abert 1848; Adams and Chavez 1956; Drumm 1982; Emory 1848; Gregg 1969; James 1962) included observations of Native American and early Euro-American settlements in their journal entries and reports. These accounts, together with the physical prominence of the pueblo, stimulated archeological interest in the area and provided a historical basis for reconstructing the pueblo's culture history.

The history of archeological investigation at Pecos National Historical Park spans a period of more than one hundred years, beginning in the late 1800s. As a result of its long and diverse archeological history, a wide variety of archeological projects—mapping, excavation, testing, reconnaissance survey, systematic survey, architectural documentation, and resource specific analytical studies—have been conducted at the park. These investigations have ranged in scope from site-specific to regionwide, reflecting changing trends in archeological methodology and in later years, changing National Park Service management concerns.

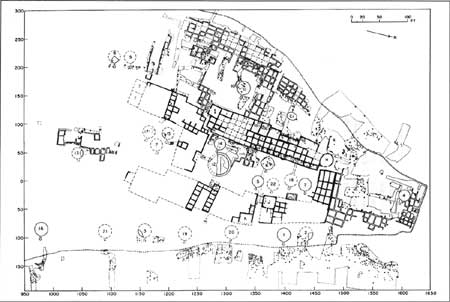

The vast majority of archeological work, particularly in the early years, was concentrated in the "core area" of the park (see Figure 1.2) focusing on Pecos Pueblo's extensive architectural remains and midden deposits. In contrast, investigations of land surrounding the pueblo were few and far between and targeted only the most prominent pueblo sites. It is only in more recent years that the peripheral areas of the park have become the subject of more intensive archeological investigation.

This chapter presents an overview of the previous archeological work conducted within the Upper Pecos Valley, summarizing the activities and accomplishments and overall contribution to our present-day understanding of Pecos' culture history. The cumulative results of these investigations formed the foundation for the design of the Pecos Cultural Resource Inventory Survey and provide the framework for its subsequent analyses and conclusions.

The Beginnings of Pecos Archeology

Adolph Bandelier, renowned Southwestern archeologist and ethnologist, conducted the first systematic archeological investigation of the Upper Pecos Valley in 1880. Although his visit to Pecos was brief, Bandelier's observations resulted in the compilation of detailed notes, plan views, and cross sections of the Pecos Pueblo and Mission complex as well as general descriptions of several other sites scattered across the valley (Bandelier 1881, 1892). As with other archeological studies of this time period, Bandelier's work was largely descriptive, documenting site setting, layout, size, construction method, and features. Drawing on his field observations and the results of his historical and ethnographic research, Bandelier was the first to propose a formal classification of the Pecos area culture sequence (1881:104-125). As the first archeologist to formally investigate the Upper Pecos Valley, Bandelier is credited with putting Pecos Pueblo on the "archeological map." His documentation efforts resulted in the preservation of significant, now irretrievable, archeological data, and his findings served as a starting point for the subsequent development of broader regional chronologies.

Building on Bandelier's ethnohistorical and archeological findings and recognizing the importance of preserving Pecos Pueblo's fragile history, Edgar Hewett continued the investigation of Upper Pecos Valley archeology in the early 1900s. In his 1904 American Anthropologist article, Hewett draws on the results of his own archeological observations and ethnographic research, as well as F. W. Hodge's ethnographic notes from the late 1890s in defining a site typology for the Upper Pecos Valley and proposing a regional Puebloan culture sequence (Hewett 1904:426-439).

Recognizing the significance of aggregation—which has continued to be an important topic in Pecos archeological research—Hewett noted that according to Jemez tradition, "Ton-ch-un" or Rowe Pueblo, located roughly 6.4 km (4 mi) south of Pecos Pueblo, was the last of seven or eight "outlying villages in Pecos territory to be abandoned as the process of concentration went on" (Hewett 1904:433). Hewett attributed population aggregation to defensive needs and noted resulting changes in the Pecos population's social, linguistic, and ceremonial life. Although his interpretations were only briefly summarized and preliminary in nature, Hewett's work helped define chronological development, site variability, and cultural change within the Pecos Valley. Within the context of turn-of-the-century Southwest archeology, Hewett, like Bandelier, demonstrated a "precocious interest in Southwestern chronology and made some fairly accurate guesses about [the] sequences there" (Willey and Sabloff 1980:51).

The Kidder Years

Coinciding with methodological changes in the field of archeology during the first half of the twentieth century, stratigraphic excavation and chronological classification characterize the next phase of archeological investigation in the Upper Pecos Valley. Stratigraphic excavation was introduced to the Southwest by Nels C. Nelson in the Galisteo Basin, 23 km (14 mi) southwest of Pecos Pueblo (Nelson 1914). Following Nelson's lead, A. V. Kidder used stratigraphic excavation techniques to pursue his archeological investigation of Upper Pecos Valley sites. Attracted by the deep, ceramic-rich midden deposits and long occupation of Pecos Pueblo, Kidder intended to use the stratigraphic findings to develop a local ceramic typology, site chronology, and ultimately an understanding of the Rio Grande Valley Puebloan culture sequence.

Between 1915 and 1929, Kidder, under the auspices of the Phillips Academy of Andover, Massachusetts, conducted ten seasons of field excavation within what is now Pecos National Historical Park (Kidder 1916a, 1916b, 1917a, 1917b, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1924, 1925, 1926a, 1926b, 1932, 1951, 1958). Under his direction, 12-15 percent of the Pecos Pueblo site area was excavated. Midden deposits up to 6 m (20 ft) deep, a few hundred rooms, 21 kivas, more than a thousand burials, and "literally millions of sherds" (Kidder 1932:4), stone, bone, shell, and textile artifacts were uncovered in the course of the excavation (Hooton 1930; Kidder 1958) (Figures 2.1 and 2.2).

|

| Figure 2.1. Alfred Kidder in the excavations at Pecos Pueblo, ca. 1915. View south, mission church in left background. Photo courtesy Museum of New Mexico, negative number 12943. |

|

| Figure 2.2. Kidder's 1916 stratigraphic excavations in the midden on the east slope of the Pecos mesila—"face of Text X, showing bottom (?) three cuts in place." Photo courtesy of Archives, Laboratory of Anthropology, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe, Negative number 435, Kidder-Pecos Collection. |

Using field provenience data and post-field ceramic attribute analyses, Kidder identified changes in vessel form and technology within a chronological context. His systematic analysis and innovative interpretation resulted in the classification of the local pottery types (Kidder 1932; Kidder and Amsden 1931; Kidder and Kidder 1917; Kidder and Shepard 1936), providing a chronological framework for reconstructing Pecos Pueblo's cultural history and serving as a "base for departure" in the development of a more regional Rio Grande glaze pottery typology (Mera 1933:2).

Supplemental to Kidder's interpretation of Pecos' ceramic typology and equally significant to the advancement of Southwest archeology, Anna Shepard, in affiliation with the Laboratory of Anthropology, conducted technological analysis of the Kidder excavation ceramics (Bishop 1991:52). The large size of Pecos Pueblo's ceramic assemblage, Kidder's newly established typology, and the pueblo's continuous occupation provided an excellent opportunity for a ceramic technology study. With the intent of recreating the history of pottery making at Pecos Pueblo and focusing on glaze ware ceramics, Shepard recorded technological characteristics, such as shaping, finishing, and firing, and used petrographic analysis to determine the types and proportions of materials—clay, pigment, and most importantly, temper—used in ceramic production.

Shepard's work exemplified early efforts at merging scientific methodology and archeological analysis (Willey and Sabloff 1980:157). Her analyses resulted in the identification of several type-specific technological features supporting and refining Kidder's ceramic typology, and of even greater significance, her petrographic analysis enabled her to compare Pecos ceramic materials with known source areas in the Upper Rio Grande. As a result, Shepard identified both local and nonlocal ceramic types in the assemblage and noted changes in the types and proportions of imported wares over time (Kidder and Shepard 1936). Like many archeological studies of that time period, chronology building and typology classification were the original motivation for her analysis. In the process, however, Shepard opened a new avenue of study, using ceramic production and trade as a tool in the reconstruction of Southwest Puebloan culture history.

The skeletal remains resulting from Kidder's excavations were another focus of scientific study. "No less than 1938 burials came to light at Pecos" (Kidder 1958:279) and from these, the skeletal remains of almost 1,000 individuals were examined documenting age, sex, bone, cranial, and pathological observations (Hooton 1930). By tallying the number of burials per ceramic period and mean annual death rate, Hooton estimated a total population of 50,000 over the course of the pueblo's occupation. He does acknowledge that this number seems "impossibly high" (Hooton 1930:342), in part due to some incorrect assumptions; however, the pattern of increase and decline reflected by his numbers shows significant growth during the Glaze II period (A.D. 1400-1450) (Hooton 1930:349), as would be expected in association with pueblo growth during a period of aggregation.

In addition to the artifact and skeletal studies, Kidder included architectural remains in his classificatory and chronological analyses. Based on his understanding of the local ceramic sequence and his observations of the newly exposed architecture, Kidder identified several spatially and chronologically distinct architectural features within the pueblo. Beneath the prominent North Pueblo or Quadrangle at the north end of the mesilla, he recognized the remains of several early, pre-Glaze architectural features including a "sizeable pueblo" (Kidder 1958:55) (Figure 2.3). Using the associated black-on-white ceramic assemblages as temporal indicators, Kidder dated these features between A.D. 1200 and 1315, pushing back the previously assumed beginning occupation of A.D. 1400 an additional 200 or so years.

As part of the excavation recording, Kidder documented architectural attributes (construction technique, materials, layout, etc.) and used this data in conjunction with information gleaned from the historic records to reconstruct the pueblo's architectural growth and development. Although much of the early architecture was left unexcavated, Kidder did observe some significant differences between early and late architectural styles. Prior to the 1400s, Pecos architecture appeared to be the result of unplanned, sporadic building episodes characterized by periods of remodeling and additions. In contrast, the layout of the later architecture suggests single-episode construction according to a preconceived design. Kidder (1958:63) bases his conclusion on the comparison of the "straggling one-story [Glaze III] community" to the "compact, four sided" post-1400 Quadrangle, interpreting this change as a necessary response to population aggregation and the growing need for defense during the later Puebloan periods (Figure 2.3).

Kidder's investigations also touched on what has become another ongoing research concern at Pecos—the extent of Plains influence, interaction, and trade at the Pueblo. Kidder uncovered an "abundance...of certain artifacts of eastern derivation," most of which were found in association with Glaze V (A.D. 1500-1700) and later deposits (Kidder 1958:313). These findings, the absence of Plains artifacts at pueblo sites farther west, and historic documentation of Plains presence (Harrington 1916; Hull 1916; Winship 1896), led Kidder to conclude that Pecos Pueblo served as a thriving trade center for Pueblo-Plains exchange. Subsequent work by Shepard documenting nonlocal pottery types in the Pecos assemblage supported Kidder's premise of the pueblo's role as "middleman" between the northern Rio Grande pueblos and eastern Plains tribes (Kidder and Shepard 1936).

Given the state of Southwestern archeology during the first half of the twentieth century, Kidder's investigations at Pecos Pueblo and mission were groundbreaking in both extent and methodology. Kidder's approach toward excavation, data recording, analysis, synthesis, and publication set new standards in the field of archeology. His synthesis established the framework for reconstructing Upper Pecos Valley culture history and broader Southwestern regional studies, and more importantly, his concerns with the "need for system, for clearer definitions, and for synthesis" (Woodbury 1973:39) pioneered the advancement of archeology into the professional discipline it is today.

Concurrent with Kidder's investigations at Pecos Pueblo and following his stratigraphic methodology, several ancillary excavations were conducted at other large multiroom pueblo sites in and near the park. Four sites were investigated: Loma Lothrop, northwest of the mesilla; Dick's Ruin in the southern portion of the park; Rowe Pueblo, south of the park near the present day village of Rowe; and Forked Lightning Pueblo, several hundred meters west of Pecos Pueblo (see Figure 1.3). Although the work performed and resulting documentation varied from project to project, these excavations, collectively and individually, confirmed the presence of large, dispersed pre-1400 pueblo communities occurring within the Pecos Valley prior to Pecos Pueblo aggregation.

The excavations at Loma Lothrop and Dick's Ruin are poorly documented. Scheick (1989) attributes the Loma Lothrop work to Sam Lothrop in 1926; however, field note references to this work (Kidder 1920; Vaillant 1915) suggest earlier excavation. Dick's Ruin was excavated in 1926 by H. D. Skinner of Otago University, New Zealand in association with the Phillips Academy. Fifteen rooms and one corner kiva of the C-shaped coursed adobe pueblo were exposed (Kidder 1958:47).

In 1917, Carl Guthe excavated Rowe Pueblo hoping to gain an understanding of the earlier "Black on White culture" represented at the site (Cordell 1998; Guthe 1917). Although only a portion of the pueblo was excavated—the south plaza and the adjacent roomblocks—substantial architectural and artifact data were collected, and three distinct building episodes were defined (Cordell 1998; Guthe 1917). Kidder investigated Forked Lightning Pueblo, another early black-on-white site (Kidder 1958:5-46) (see Figure 1.3). Between 1926 and 1929, he excavated portions of the pueblo's deep midden deposits and extensive mounds. Kidder (1958) noted the same rambling, unplanned construction design seen at the nearby "Black-on-white House" on the mesilla. Based on Forked Lightning's pottery types, he assigned a date range of A.D. 1225-1300, an occupation interval that ended slightly earlier than the final occupation dates at nearby Loma Lothrop, Dick's Ruin, and Rowe Pueblo.

The Kidder years also saw the beginnings of a ruins preservation program. Unlike the ongoing archeological investigations, the focus of the preservation work was the Spanish, rather than Puebloan, architecture. In 1915, during Kidder's first field season, Jesse Nusbaum directed the stabilization of the eighteenth century church at the south end of the mesilla. Concrete wall supports were installed and various wall repairs were conducted (Ivey 1996; Nordby et al. 1975:2). Excavation in support of the stabilization work exposed lower interior walls and foundations and over one hundred burials beneath the church floor (Hooton 1930:12). Nusbaum left no records other than a few photographs of the church architecture and a map depicting the church and convento plan view (Nordby et al. 1975:2). As the only documentation of this work, the photos provide a crucial glimpse of the 1915 prestabilized church, and the map is an important key for "deciphering the entangled mass of multiple layers of use and reuse" throughout the convento (Ivey 1996:6-6).

Several years later, in 1925, Kidder conducted additional excavations in the church convento area, opening a few test pits and trenches (Ivey 1996). Under Kidder's direction, Susan Vaillant excavated a trench just west of the church. Several burials and a segment of the church facade were exposed in the process (Hayes 1974:xii).

The State Monument Era

Following the conclusion of the Kidder excavations, archeological activity within the Upper Pecos Valley took on a more sporadic character with focus temporarily shifting away from the mesilla. Texas Technological College, under the direction of William Holden, began excavating Arrowhead Ruin, a roughly 100-room pueblo located north-northwest of Pecos Pueblo within the present-day Glorieta Battlefield Subunit (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3). Over the course of six field seasons, between 1933 and 1948, the college field school excavated a total of 79 rooms and one kiva (Holden 1955). Upon completion of the excavation, the kiva and several of the rooms were restored and stabilized. Based on tree-ring dates and ceramic types, Jane Holden (1955:103) assigned an occupation period of A.D. 1370-1450, slightly later than the other early pueblos identified in the valley. She (1955:113) suggests that occupants of the site may have originated from Pecos Pueblo and "leisurely" returned there after a time at Arrowhead Ruin.

Some time concurrent with the Arrowhead excavations, H. P. Mera investigated Shin'po, LA 267 (also known as Hill House), a small pueblo south-southeast of Pecos Pueblo (see Figure 1.3). Mera's investigation established the presence of another early preaggregation pueblo in the valley but generated little additional information. The only documentation associated with his work is a very brief site description written on a 1939 Laboratory of Anthropology site card. Recent observations at the site noted previous excavation in at least two of Shin'po's rooms (Head 1997a), but whether or not this work can be attributed to Mera's investigation is unknown.

With the establishment of the Pecos State Monument in 1935 and in anticipation of the four hundredth anniversary commemoration of Coronado's entrada, the mesilla again became the focus of intense archeological activity. An extensive government-supported excavation and stabilization project was conducted under the combined efforts of Edwin Ferdon, John Corbett, J. W. Hendron, and William Witkind (Metzger 1990b). Unlike Kidder's research oriented investigations, the goal of this work was "ruins display and vessel acquisition" (Nordby 1990). Over a three-year period, between 1938 and 1940, the defensive wall and approximately 100 rooms in the northern portion of the South Pueblo were excavated, mapped, and stabilized; Kiva 16 was re-excavated and reconstructed; a portion of the convento was excavated, the entire convento mapped; and the eighteenth century church was stabilized (Corbett 1939; Hendron 1939; Nordby et al. 1975; Witkind 1940).

Confined by the time constraints imposed by the upcoming Cuarto Centennial and using a large untrained labor force, huge quantities of dirt were hastily removed and numerous architectural features exposed and stabilized. Although field notes, photographs, daily logs, and maps were compiled, a final report was never completed. It has only been in recent years, due to the efforts of James Ivey, National Park Service research historian, that the records have been interpreted and the full extent of the work has come to light (Ivey 1996). Nonetheless, given the vast quantities of cultural fill and architecture exposed by the project, the available documentation represents an unfortunately incomplete record of the work performed.

The years following the Cuarto Centennial were relatively quiet with only a few archeological investigations conducted on park lands between the early-1940s and mid-1960s. Three separate excavations were documented during this period. Unlike most of the earlier excavations, these projects were limited in scope and duration and focused on smaller, more varied sites peripheral to the mesilla.

In 1956, Stanley Stubbs and Bruce Ellis, in affiliation with the Laboratory of Anthropology, excavated portions of the Lost Church, the first of the "four churches of Pecos" (Hayes 1974:19). The Lost Church, also known as the Ortiz Church (Ivey 1996), had been described and mapped by Bandelier in 1880 (Bandelier 1881:88) and remapped and tested by Kidder in 1925 (Ivey 1996:3-1). Despite these previous efforts, additional mapping and testing were proposed in order "to prepare a more accurate ground plan...and to determine if possible the age of construction and use" (Stubbs et al. 1957:68).

Based on their historical research and excavation findings, Stubbs et al. (1957:85) propose a construction date during "the first two decades of the 1600s," the earliest period of mission architecture represented in the park. They also concluded that the church was never completed, its materials salvaged for later construction on the mesilla 300 m (984 ft) south. Recent investigations (Ivey 1996:3-13) have confirmed this supposition, identifying yellow adobe bricks originally associated with the Lost Church construction in later walls of the South Pueblo.

In association with the Lost Church excavation, Stubbs et al. (1957) excavated a suspected shrine a short distance to the northeast. The shrine lacked the characteristic architecture and elevated setting of other Pecos shrines; however, its artifact assemblage was comparable to shrine objects identified in the course of the Kidder excavations (Kidder 1932). Given the shrine's location near the church, Stubbs et al. (1957:91) proposed that it might have been established to counter the influence of the newly imposed church upon the native Pecos population.

In 1963, a salvage excavation project was conducted along the proposed route for Interstate 25 (I-25) to the south of the monument (Wood 1963, 1973). This was one of the first of many archeological projects conducted in the vicinity of the park in response to New Mexico State Highway improvement projects (Alexander 1964; Gaunt 1998; Lent 1992; Maxwell 1985; Moore 1992; Moore et al. 1991; Oakes 1990, 1991, 1995; Willmer 1993; Zamora 1990) and growing government concern with mitigating development impacts on cultural resources. Four sites were excavated prior to I-25 construction, exposing three single room structures and a lithic and ceramic scatter. One of the sites, LA 6846, falls within present-day Pecos National Historical Park boundaries.

Wood's excavations represent one of the first efforts to investigate small site architecture and settlement in the vicinity of Pecos Pueblo. He notes that all three structures were similar in architectural style with sparsely associated artifacts suggestive of short-term occupation (Wood 1963:31). Temporal affiliations ranged from the late fifteenth to the early eighteenth century. Based on his findings, Wood supported Kidder's assumptions concerning Pecos Pueblo aggregation by suggesting these three small structures represent seasonally occupied field houses used by the occupants of Pecos Pueblo.

National Park Service Projects

In 1965, the establishment of Pecos National Monument triggered a renewed interest in site display, interpretation, and ruins preservation. As a result, archeological activities shifted back to the most visitor-accessible and architecturally prominent sites on the mesilla (Hayes 1970; Matlock 1974; Metzger 1990b; Nordby 1990; Nordby et al. 1975; Pinkley 1968; White 1993). The mission complex, because of its substantial architecture and need for preservation, became the primary focus of this government-funded work.

With stabilization as the motivating force, the "topical direction of Pecos archeology [changed] from Puebloan studies to historical and Euro-american ones" (Nordby 1990:23). This shifting emphasis between the prehistoric Puebloan components and the Spanish-Pueblo contact period components characterizes much of the history of archeological investigation at Pecos. Church and convento excavations prerequisite to stabilization were conducted by the National Park Service under the direction of Jean Pinkley and Alden Hayes from 1966-1969 and 1969-1970, respectively (Figure 2.4). The scope of work for the church and convento excavation and stabilization was extensive, and in retrospect, overwhelming. Funding and scheduling needs were greatly underestimated given the area and architecture involved (Ivey 1996; Nordby et al. 1975). Pinkley's efforts to complete the proposed work were further complicated by inconsistencies in the previous records and by her misconceptions concerning the extent of previous work. The convento had not been completely excavated as she had assumed and required considerably more excavation time than had been anticipated (Ivey 1996). As a result, Pinkley's goal of interpreting the various convento construction episodes was never realized, project documentation was sparse and poorly organized, and the project's contributions to the archeological record were limited.

|

| Figure 2.4. Excavations in preparation of stabilization in the Pecos mission convento, 1970. Pecos National Historical Park. |

Despite these problems, extensive portions of the mission complex were excavated and stabilized, and several significant discoveries were made. Pinkley's excavations in the eighteenth century church uncovered the remains of an earlier seventeenth century church foundation. This discovery verified the presence of a fourth church at Pecos (Hayes 1974) and resolved the long recognized discrepancy between the historical record and on-the-ground archeological observations (Ivey 1996). Three new features—a kiva, a tower, and a post-Pueblo revolt root cellar—were identified within the convento (Nordby 1990). The kiva was the most intriguing find, stimulating a variety of suppositions explaining its location within the mission complex. Hayes (1974) concluded that the kiva was an attempt by the Pueblo people to "resanctify the scene" following the Pueblo Revolt (Nordby 1990:24). Based on recent investigations at Pecos and other Franciscan missions in northern New Spain, Ivey (1997) asserts that this kiva was constructed by (or for) the Franciscans early in their tenure at Pecos to facilitate Indian conversions.

Excavation activities were also extended to other Spanish Colonial structures adjacent to the mission complex—the first time secular Spanish remains were investigated in the park. In 1970, Hayes excavated to the west of the mission complex. He focused his efforts on the Estancia, consisting of two components: the "Presidio" (also known as the "Corrales" or "Compound") and the "Casas Reales" (also referred to as the "Convento Annex" or "Casa") (Ivey 1996:5-15). As a result of this work, Hayes (1974) theorized that the "Casas Reales" represented eighteenth century secular housing and the "Presidio" was used for garrisoning the troops. Subsequent to the publication of Hayes' The Four Churches of Pecos (1974), archeomagnetic sampling from one of the Casas Reales rooms indicated a seventeenth century pre-Revolt occupation. Since that time, additional dating and archeological investigation have confirmed an early seventeenth century affiliation (Ivey 1996).

Following the excavations, extensive stabilization efforts were conducted under the direction of Roland Richert and Frank Wilson, and park archeologist Gary Matlock (Nordby et al. 1975). As a result of the 1969-1974 stabilization efforts, portions of the South Pueblo, the defensive wall, the seventeenth century church foundation, the eighteenth century church, the convento, the Estancia, Square Ruin, the Lost Church, and a number of kivas were stabilized (Ivey 1996; Nordby et al. 1975). Subfloor testing was conducted in some of the South Pueblo rooms prior to stabilization, confirming the presence of earlier, underlying construction and room remodeling (Nordby 1990). As part of the final report, Matlock compiled room-by-room and area-by-area descriptions of the stabilization work, including brief summaries of the previous work episodes and available archeological and architectural data (Nordby et al. 1975). The quality and detail of this information and its relevance to the interpretation of Pecos' architectural and culture history is highly variable.

During the same period, along a more research-oriented vein, James Gunnerson of the University of Nebraska conducted reconnaissance survey and test excavations in search of Apache sites near Pecos Pueblo (Gunnerson 1969b; 1970a, 1970b; Gunnerson and Gunnerson 1970). Although numerous other archeologists had wandered park lands in search of site remains, Gunnerson was the first to incorporate reconnaissance survey of park lands into his project design. This shift in emphasis, from site-specific excavation to broader area investigations, reflects changing trends in archeological research and increasing recognition of survey methodology and surface recording as a valid investigative approach.

Over the course of three seasons, Gunnerson identified several Apache sites based on the presence of micaceous Apache sherds and circular rock features. Nine Apachean locales were identified within the monument area (Gunnerson 1969b, Gunnerson and Gunnerson 1970), although another version of Gunnerson's site map shows as many as 23 different locales in the vicinity of the Pueblo. A few sites were also identified on Forked Lightning Ranch lands, but other than mentioning one rock ring above the Pecos River, Gunnerson's research was focused on sites within the monument.

Gunnerson's investigation of "Area C" east of the church is of particular interest (Figure 2.5). Excavations uncovered the remains of a burned, pole and clay daub dome-roofed structure in association with Puebloan and Apache ceramics (Gunnerson 1970b; Gunnerson and Gunnerson 1970). Comparison of the structural remains with other Jicarilla Apache pole and earth structures (Gunnerson and Gunnerson 1970:4), the presence of Ocate Micaceous ceramics, and historical accounts of Apache camps in the vicinity of Pecos Pueblo led the Gunnersons to conclude probable Apachean affiliation.

|

| Figure 2.5. Gunnerson's excavations east of the Pecos church, 1970. Pecos National Historical Park. |

Gunnerson also excavated a few nearby Christian burials and a Puebloan shrine to the northeast. Referring to ethnographic research, he noted the possibility of eight Puebloan shrines in the monument area (Gunnerson 1970a:33). The Pecos Cultural Resource Inventory Survey documented eight shrines within the park, though only three within the monument area.

In 1971, another reconnaissance survey was conducted within the park focusing on the petroglyphs and pictographs, a largely unstudied resource up until this time. Robert Lentz and Eugene Varela, both seasonal rangers at the park, conducted reconnaissance survey among the bedrock outcrops and talus boulders north of Pecos Pueblo (Lentz 1971). They recorded 45 petroglyph panels and 33 grinding surfaces, compiling locational maps and detailed sketches of the individual panels. Lentz's report is largely descriptive summarizing the types, condition, and locations of the petroglyphs and grinding features. He does note patterns in the occurrence of certain motif types and an apparent association between petroglyph locations and a nearby mesilla shrine (Lentz 1971; Nordby 1990).

Privately owned ranch lands surrounding the monument remained relatively uninvestigated, their archeological sites largely unknown, until the mid-1970s. This situation changed dramatically with the initiation of two concurrent but separate research projects, both focusing on the cultural resources of Forked Lightning Ranch lands. In 1975 and 1976, Dietrich Fliedner, a German geographer, conducted a one-man reconnaissance survey of both ranch and monument lands. Fliedner's goal was to collect data in support of his "theory of society in space and time" using the Pecos Pueblo population as one of his study groups (Fliedner 1981). His wanderings across the park resulted in the identification of more than 1,300 sites, many of which were partially collected. The resulting collection, grab samples of ceramics and a small number of flaked lithics, is curated at the National Park Service in Santa Fe. Unfortunately, Fliedner neither described his field methodology, nor provided any site specific data in his final report. He did compile a hand-drafted map of the site locations, but without associated site records, the map is of limited utility.

During this same time, the National Park Service began its first systematic cultural resource survey of the monument and portions of the surrounding Forked Lightning Ranch lands. The primary goal of this project was to obtain much-needed information concerning "small site archeology" in the park and Upper Pecos Valley area (Nordby 1993). Under the direction of National Park Service archeologist Larry Nordby, the survey sought to document the types, distribution, and relationship of these sites to each other, Pecos Pueblo, and the surrounding landscape. After recording a small number of monument area sites in 1975, Nordby developed a standardized recording format designed to capture archeological, environmental, and management data. In response to the anticipated continuous, low density artifact scatter across the park's landscape, sites were defined based on the presence of features rather than on the limits of artifact distribution (Nordby 1993).

A total of 125 core monument sites and 88 Forked Lightning Ranch sites was recorded over the course of the survey (Nordby 1992, 1993). Archaic, Puebloan, Plains, and Euro-American sites were identified. Recorded structures ranged in size from one to more than 100 rooms, although one to five room structures were most common. A wide variety of features were noted, including petroglyph panels, isolated wall segments, bedrock mortars, cairns, fire-cracked rock, hearths, and rockshelters.

Despite extensive research and the completion of several information-filled chapters (Nordby 1990), the survey report was never finished. In lieu of this, a brief management report and summary of survey findings were compiled (Nordby 1992, 1993). Although the full research potential of this project was never realized, as the first systematic cultural resource survey at Pecos, it made a significant contribution to our understanding of the park's cultural resources. The documentation of more than 200 sites broadened management's perception of the resource, improved the existing site database, and provided baseline data which assisted design of the current inventory survey.

During the years following the survey, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, three pit structures were discovered in the park (Nordby and Creutz 1993a). Despite numerous archeological investigations, this was the first evidence of Developmental Period sites on park lands. All three pithouses were identified as a result of subsurface excavations: the Sewer Line Site (PECO 207) and the Propane Tank Site (PECO 61) were discovered during construction activities associated with park facilities development, and Hoagland's Haven (PECO 53) was located during test excavations of an overlying two-room surface structure. The Sewer Line Site and Hoagland's Haven pithouses were 100 percent excavated, but only a quarter of the Propane Tank Site pithouse was exposed (Nordby and Creutz 1993a). Tree-ring dates from Hoagland's Haven and archeomagnetic dates from the Sewer Line Site indicate occupation dates ranging between A.D. 800 and 850. Nordby and Creutz (1993a) suggest these pithouses may represent a portion of a larger pithouse village. Subsequent magnetometer tests (Korsmo 1983) noted anomalies in the area, but the results are inconclusive. In support of the supposition, it is interesting to note that a fourth pithouse was identified in the same general area during 1994 mitigation excavations associated with proposed facilities construction (Akins 1994:16-21). Two more pithouses were located during excavation of the common grave for the 2,000 individuals reburied at Pecos in 1999 (Judy Reed, personal communication 2001).

Prior to the Nordby and Creutz pithouse excavations, the earliest occupation in the park was thought to date circa A.D. 1100, suggested by early ceramic assemblages at Forked Lightning Ruin. Discovery of the pithouses pushed the occupation dates back another 200 to 300 years. The presence of Alibates flint in the pithouse assemblages also raises the possibility of earlier Pecos-Plains contact than had been previously thought (Nordby and Creutz 1993a). Other than the above-mentioned pithouses, archeological evidence representative of the Developmental Period is very limited, and the intensity and extent of pithouse occupation within the Pecos Valley is still largely unknown.

Several other test excavations were conducted within the monument area during the late 1970s and early 1980s. These include testing at Square Ruin (LA 14081)—a large pentagonal shaped masonry structure west of the Spanish Estancia, South Pueblo, and the seventeenth century church midden (McKenna 1986; Nordby 1976a, 1976b, 1976c, 1983a, 1983b; Nordby and Creutz 1993b; Nordby and Matlock 1972, 1975). Motivated by differing research, stabilization, and/or mitigation concerns, the scope and results of these projects vary widely. The 1982-1983 Square Ruin excavation was the most exploratory, although research questions concerning cultural affiliation and site function were largely unanswered. The discovery of an early pit structure—either a Developmental pithouse or a Coalition kiva—did little to clarify the affiliation and will require additional excavation.

The most significant work conducted within the Upper Pecos Valley during this period was at Rowe Pueblo, south of the park. Relatively untouched since Guthe's 1917 excavations, the pueblo was once again the focus of extensive archeological investigation. Testing, excavation, and survey (intensive and reconnaissance) were conducted within and adjacent to the pueblo through the cooperative efforts of the University of New Mexico, New Mexico State University, and the National Park Service (Anschuetz 1980; Cordell 1998; Morrison 1987; Wait 1981; Wait and Nordby 1979).

Initial testing and excavation conducted in 1977, 1978, and 1980 were designed to identify population origins, span of occupation, relationship to other early pueblos in the valley, and the role of trade in the pueblo's development (Wait 1981). The results of tree-ring dating, ceramic analyses, and architectural observations led to the conclusion that all three plazas postdate the thirteenth century. Although the final form of the dwelling implies it was carefully designed, the complex stratigraphy suggests earlier periods of remodeling and unplanned building. Wait (1981) proposes a relatively short occupation span of 70 to 100 years dating around A.D. 1330 to 1400. Cordell (1998) notes that despite the dendrochronological and archeomagnetic findings, a pre-1300 occupation of the site is possible, as suggested by underlying adobe walls and use surfaces in the southern portion of the site.

Fieldwork at Rowe resumed in 1983 and 1984, and included additional excavation, detailed site mapping, and proton magnetometer survey (Cordell 1998). Research continued to focus on temporal, settlement, and trade issues, in addition to searching for indications of agricultural intensification and evidence of restricted access to certain artifact types indicative of the existence of local site hierarchies (Cordell 1998:202). Cordell (1998) identified six construction episodes within the pueblo with an occupation span of A.D. 1250-1425. Based on interpretations of the pueblo stratigraphy, masonry style, ceramic assemblage, and burial population, Cordell attributes the pueblo's establishment to local, rather than immigrant, populations. Aggregation at the site may "have begun as early as the 1240s or 1250s for the adobe ruins but certainly in the 1340s and 1350s for the masonry structures" (Cordell 1998:89). There was no evidence of agricultural intensification or restricted access to certain ceramic types at the pueblo, nor did the site assemblage indicate interaction between Rowe Pueblo and Plains groups to the east.

In addition to the on-site investigations, two archeological surveys were conducted in the pueblo vicinity to determine the extent of occupation and diversity of site types in the surrounding Pecos Valley. In 1980, a systematic archeological survey was conducted within a 3 km2 (1.2 mi2) area immediately adjacent to the pueblo (Anschuetz 1980; Cordell 1998). In 1984, transect and reconnaissance surveys focused on an 87 km2 (33.6 mi2) area north and northwest of Rowe Pueblo, investigating a total of 6 km2 (2.3 mi2) (Cordell 1998; Morrison 1987). Portions of the later survey area included some of the Forked Lightning Ranch lands that have since become part of Pecos National Historical Park.

A total of 71 sites, ranging from late Archaic to nineteenth century Euro-American, was identified as a result of the surveys. The documentation of several late Archaic sites was a significant addition to the previously meager Upper Pecos Valley Archaic database. Obsidian samples were collected from a number of sites in lieu of, or as an alternative to, ceramic dating. The resulting obsidian hydration dates vary widely, in some cases spanning several thousand years within a single site (Cordell 1998). Whether or not these broad date ranges reflect actual site occupation, patterns of reuse, or problems inherent to the obsidian dating technique is unclear (Head 1997a:26).

Recent Years

Since the completion of the Rowe project field work, many of the archeological investigations in the Upper Pecos Valley have been motivated by compliance with cultural resource protection laws. State highway improvement projects, local residential development, and park facilities construction have triggered a variety of small survey and excavation projects within and adjacent to park lands. In addition, stabilization work and historic research have prompted several small National Park Service projects within the park.

The proposed improvement of portions of State Road 50 has resulted in various phases of archeological survey, testing, and excavation prior to project clearance. Eighteen sites including Puebloan, unknown Native American, and nineteenth and twentieth century Euro-American remains were identified along roughly 9.7 km (6 mi) of NM 50 between Glorieta and Pecos (Maxwell 1985; Moore 1992; Zamora 1990). Some of these sites lie within the Pecos National Historical Park Pigeon's Ranch Unit.

Twelve sites were tested to determine the nature and extent of subsurface remains (Moore et al. 1991; Oakes 1991, 1995). Archeological findings at the Native American sites were "compatible with the expected land-use patterns of the region during the Pueblo period" (Oakes 1991:65) and were consistent with the site types identified during the previous National Park Service survey (Nordby 1992, 1993). Investigation of the historic sites, however, opened up a different chapter of Pecos Valley history—the Civil War and nineteenth century Euro-American settlement.

Two historic sites, Pigeon's Ranch and the Glorieta Battlefield, became the focus of intensive site investigation (Oakes 1995). Both sites are now within the Pigeon's Ranch Unit of the park. Excavation and archival research were conducted by the Office of Archeological Studies in 1986 and 1989 (Oakes 1995). As a result of the testing project at Pigeon's Ranch, several historic features were encountered, including a well dating to the 1850s, remains of an 1880s saloon, and a house foundation, cellar, and gas pump locale dating from the 1920s through 1950s. The ranch history, architectural chronology, and layout were reconstructed from both archeological and archival evidence.

No subsurface features were located in association with the Glorieta Battle during the highway right-of-way testing (Oakes 1995), although a Confederate mass burial was found on private land nearby, southeast of Pigeon's Ranch (Oakes 1990). The burial, originally discovered by the landowner during house construction, was excavated in 1987 by the Office of Archeological Studies with volunteer time. Thirty-one individuals and numerous associated artifacts were uncovered during the excavation. The human remains were submitted for skeletal, DNA, bone tissue, and parasitological analyses prior to reburial at an alternate site. Archival research was conducted to gather information on the battle and its participants with hopes of being able to identify the individuals buried within the mass grave (Oakes 1990).

Another highway right-of-way survey and testing project was conducted along a five-mile stretch of NM 63 bisecting the park west of the former monument area (Gaunt 1998; Lent 1992; Willmer 1993). Sixteen sites, ranging in affiliation from Archaic to recent historic, were identified (Lent 1992; Willmer 1993). Ten of these sites, including a portion of the Santa Fe Trail, were tested prior to project clearance (Gaunt 1998). The methods used in the investigation of the Santa Fe Trail segment are of particular interest. Electromagnetic soil conductivity testing was used to map the trail route in areas where ruts were no longer visible (Gaunt 1998). As a result, a previously unidentified section of trail was located. To supplement the electromagnetic testing, mechanical trenching was conducted across two trail segments allowing for the examination of their soil profiles. Soil anomalies coinciding with the rut alignments were detected in both trenches confirming the trail locations (Gaunt 1998).

Other small-scale archeological investigations were conducted by the National Park Service within the park during the late 1980s and early 1990s. In an effort to update his 1976 survey, Nordby created a more detailed site recording format and began transferring the original site data onto the newly revised form. Between 1988 and 1993, he made periodic visits to the park, revisiting previously recorded sites and collecting additional data. This effort resulted in the data transfer or re-recording of 40 monument area sites.

A small acreage survey along the proposed south boundary fence line recorded four new sites in 1992 (Metzger 1992). Three parcels of land proposed for facility development were surveyed in 1993, resulting in the identification of four Native American sites and numerous Euro-American historic features (Eininger 1994). Subsequent to the 1993 survey, additional surface recording and subsurface testing were conducted at one of the proposed facility locations. Mapping, surface collection, augering, and test excavations were conducted southwest of the convento across the anticipated construction zone (Akins 1994). Although no subsurface deposits or features were found within the proposed construction area, a pithouse was encountered within a test pit outside the impact area. As mentioned above, this pithouse is located in the vicinity of the three other previously excavated pithouses (Nordby and Creutz 1993a) and like the others, is situated roughly 1 m (3.3 ft) below ground level with no associated surface remains.

Stabilization projects continued to be an integral part of the cultural resource program at the park, addressing preservation needs at the mission complex and North and South Pueblos. Beginning in the early 1990s, under the direction of park archeologist Todd Metzger, the park's stabilization standards were revised. Although stabilization maintenance of exposed structural remains was still the primary goal, detailed architectural documentation and stabilization recording were incorporated into the preservation process. This new emphasis on documentation was based on the premise that architectural remains are an archeological data source with research potential, and as a result, the architectural data as well as structural fabric need to be preserved (Metzger 1990b).

Observations concerning original wall fabric, construction methods, architectural details, and previous work were recorded on a room-by-room, wall-by-wall basis (Metzger 1990a; White 1993, 1994). Construction material samples were collected, material source areas identified, and ancillary studies of mortar and adobe including grain-size, trace element, pollen, and macrobotanical analyses were conducted (Ivey 1996; White 1993, 1996).

Based on the careful field observations and the results of these analyses, several distinctive material types and construction patterns were identified within the church and convento. Although the presence of different adobe types—"red" and "black"—had been previously documented by Hayes (1974), a total of nine adobe and eight mortar types was identified within the mission complex as a result of this recent documentation process (White 1996). These types were further defined and interpreted based on information gleaned from the field observations, lab results, archeomagnetic dating, historical documentation, and previous excavation findings (Ivey 1998; White 1996). The resulting typology was placed within a chronological framework and provided a useful tool for determining construction sequence and determining structural and cultural development of the mission complex (White 1996).

This investigation of the mission complex mortar types was part of a larger multiyear research project concerning the park's Spanish Colonial resources. The results of this work are compiled in a draft "Historic Structures Report" (Ivey 1996) and represent the first comprehensive study of Pecos National Historical Park's Spanish Colonial architecture. Its significance and contribution to the park's culture history lies not only in the quantity of information contained within its pages but also in Ivey's extensive efforts to re-evaluate and interpret the findings of previous studies, the vast majority of which have "never been published or discussed in detail anywhere" (Ivey 1996:7).

Two other thematic cultural resource studies recently undertaken at the park include an ethnographic overview (Levine et al. 1994) and a cultural landscape overview (Cowley et al. 1998). The purpose of the ethnographic study was to consult with the "culturally diverse communities traditionally associated with Pecos National Historical Park" (Levine et al. 1994:1-1). As a result of consultations with Jemez Pueblo, Cochiti Pueblo, Santo Domingo Pueblo, Plains Apache, Comanche, Jicarilla Apache, and the town of Pecos, information concerning the cultural associations and traditional uses of the lands and sites within the park was collected. The cultural landscape overview (Cowley et al. 1998) examined the interactions and effect of cultural and natural forces on the landscapes within the park. Using a combination of fieldwork and archival research, cultural history themes and features extending from pre-Contact times to the present-day were delineated.

Contemporaneous with these various park projects and the multiyear Cultural Resources Inventory Survey (CRIS), numerous small archeological investigations were conducted within the surrounding Pecos Valley in response to private, community, and utility development projects. Many of these surveys resulted in negative findings, largely a result of the size, location, and previous disturbance of the proposed project areas. Others identified a variety of new sites, both Native American and Euro-American, typical of the findings of the previous projects discussed above (Fredine 1998; Futch 1995; Kramer et al. 1997; Martinez 1995; McGraw 1997; Swan 1997; Townsend 1997, 1998; Williamson 1995). One notable exception was the recording of a grid garden system at the base of Glorieta Mesa (McGraw 1997). Only a small number of agricultural features have been recorded within the Upper Pecos Valley despite intensive Pueblo settlement. McGraw (1997:22) notes the significance of this finding, citing the Rowe survey (Morrison 1987) as the only other investigation to record a grid garden system in the Pecos area (see Chapter 5 for a discussion of agricultural features located by the Pecos CRIS).

Historical Euro-American resources were the focus of two recent site-specific studies in the park. In 1995, a grist mill site along the Pecos River across from the Forked Lightning Ranch house was test excavated, and the remaining millstones were retrieved for curation at the park. The site, identified as the Cattanach Mill, was dated to the early 1900s. Although the excavation confirmed the location of the mill, the almost complete lack of associated architectural remains on the site was unexpected. The mill apparently had been dismantled in 1925 and the associated debris either hauled off, burned, or washed away by subsequent flooding of the Pecos River (White and Porter 1996).

Investigations were also conducted at Camp Lewis, the site of the Union Army encampment during the 1862 Civil War Battle of Glorieta Pass. Historic documentation placed the campsite adjacent to the Santa Fe Trail and Kozlowski's Stage Stop, however its exact location and spatial extent were unknown. A variety of field methods were implemented to determine the camp's location: conventional ground survey, metal detector transects, shovel testing, proton magnetometer survey, black-and-white and infrared aerial photography interpretation, and archival research. As a result of these efforts, camp boundaries were interpreted, based on artifact distribution and the location of several man-made anomalies (Haecker 1998).

Most recently, roughly 300 dendrochronological samples were collected from several park sites: Kozlowski's Trading Post, the North and South Pueblos, the eighteenth century mission, and three Hispanic ranches. The results of this study are reported in Appendix E of this report. Kozlowski's Trading Post samples dated mostly to the early 1900s. Despite historic documentation noting the use of Pecos Pueblo beams in the building construction, the earliest dates were in the late 1800s. Only a few reliable dates were generated for the other sites due to the preponderance of juniper in the sample collection. One corral post at PECO 541 dated to 1542, suggesting salvaging from the mesilla. Of the 120 samples taken at the North and South Pueblos, four North Pueblo samples date to the 1400s and one South Pueblo sample dates to 1542. Church samples reveal several date clusters in the 1500s, 1600s, 1706, 1880s and park repair in the 1930s.

One final investigation involving Pecos Pueblo that warrants mention is a recently completed dissertation concerning pueblo aggregation by Eden Welker (1997). Using Pecos Pueblo and San Marcos Pueblo data, Welker's goal is to "compare and contrast the maintenance of aggregation at [the] two communities" (Welker 1997:1). Her study includes extensive examination of Pecos Pueblo's previous excavations, architectural layout, population, agricultural practices, ceramic production, and trade relations. Focusing on economic factors, Welker questions the reliability of agriculture and confirms the importance of trade in maintaining the viability of Pecos Pueblo's aggregated community (Welker 1997).

Summary

The history of archeological research at Pecos National Historical Park is as varied and rich as the archeological remains which have been their focus. Over the course of the last hundred years, numerous archeologists and researchers have been drawn to the Pecos Valley, lured by the accumulated remains of several hundred years of continuous occupation and the mosaic of cultures represented. As this chapter has demonstrated, the park's multicultural past and diversity of archeological remains are the backdrop for many significant archeological findings.

The majority of archeological work at Pecos National Historical Park has focused on Pecos Pueblo and Mission—the most visibly prominent and archeologically rich of the park cultural resources. A wide variety of investigations have been conducted at this site including excavation, survey, artifact analysis, architectural documentation, archival research, and stabilization. Although the emphasis of the work has alternately focused on Puebloan and Spanish remains, pueblo development, community aggregation, Pueblo-Plains relations, the role of trade, and Spanish settlement have been recurring themes throughout much of this work.

In contrast to Pecos Pueblo's prominence in the archeological record, areas of the park beyond the mesilla have received little attention. The earlier habitations, special-use sites, and numerous campsites that characterize the surrounding area have been largely overlooked in favor of the larger, permanent habitation sites. Although a few previous investigations ventured beyond the walls of the Pueblo and Mission, recognizing the importance of small site archeology, the surrounding landscape was, until recent years, largely understudied and little known. The intent of the Pecos Cultural Resource Inventory Survey is to address this void in the archeological record, broaden our understanding of Upper Pecos Valley intrasite and intersite dynamics, and contribute to the reconstruction of the diverse culture history of this prominent gateway in the American Southwest.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

peco/cris/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006