|

Watering the Land: The Turbulent History of the Carlsbad Irrigation District |

|

CHAPTER SEVEN

Uncertainty and Evolution: The Reclamation Service's First Years

The issue of supplying water during the Carlsbad Project's first year was complicated both by the partially complete distribution system and the legal stipulations of the Reclamation Act. The act specifically stated that recipients of irrigation water could own no more than 160 acres within the project area. Such a stipulation, however, had not applied during the Pecos Irrigation Company's operation of the system, and consequently a number of landowners possessed acreages that substantially exceeded the maximum. The terms of the project agreement mandated that these excess holdings be broken up and sold, but in the absence of irrigation water in 1905 and 1906 little of this had been accomplished. Normally, these excess lands would not have been allowed to receive water, but because of the Carlsbad Project's unique circumstances it was decided to allow temporary irrigation of the excess acreages in order to save the crops and orchards they contained. Reed had pushed for these "special contracts" out of sympathy for the landowners, but he was unhappy with the results, noting that such lands were poorly cared for because their owners were no longer assured of a long-term interest in the land. Consequently, Reed recommended that the special contracts not be renewed. [1]

In contrast, the landowners involved felt that their land was being unjustly taken from them, since they had been required to subscribe to the project contract in order to receive any water at all. Not surprisingly, these individuals displayed substantial resentment towards the Reclamation Service. [2] As late as 1910, almost 4,500 acres of these "excess lands," some now devoid of water, remained within the project boundaries. Officials speculated that much of the subdivision that had taken place merely involved paper transactions to ostensibly clear the title without actually transferring control. On October 7, 1910, the Secretary of the Interior attempted to end the problem by announcing that the remaining excess acreages would be removed from the project's boundaries and other land substituted. [3] Despite these Federal actions, however, the excess lands controversy continued to reappear at Carlsbad for decades.

Additional controversy stemmed from the Reclamation Service's need to institute a collection schedule for the Federally-mandated usage fees from the project's landowners. These fees, established on a per-acre basis, included an annual maintenance and operation assessment as well as a charge intended to recoup the Federal cost of purchasing and rehabilitating the project's physical plant. Since the project was only in partial use during 1907, it was decided not to assess the construction fee that year, but a dispute arose over the date the 1908 payment would be made due. In late 1907, the Reclamation Service announced that a $3.85 per acre water fee for the 1908 growing season would be due the following March 1. This news caused an incensed Tracy to compose an angry missive to Secretary of the Interior James Garfield. Tracy noted that it had been two to three years since the farmers had been able to grow irrigated crops, and that it was both impossible and wrong to insist on payment in advance under those circumstances. Garfield declined to intervene on Tracy's behalf, noting that water service would not be terminated until a landowner's fees were two years in arrears. Thus, a farmer could retain service by simply making each payment one year late. [4]

The Pecos Water Users Association took up the payment issue early in 1908, and over the next few months the group issued a volley of letters to Garfield and other government officials requesting deferment of the construction assessment due March 1, 1908. The group's plaintive requests, highly reminiscent of their lobbying effort in 1905, finally met with success in November 1908 when Hill wrote the Reclamation Service director recommending that the users' association request be granted. [5]

While the fee schedule remained under debate, Tracy and his associates continued to complain about the Reclamation Service's management of the Carlsbad Project. In June 1908, Reed learned that Tracy had sent a letter to Reclamation Service officials "not only criticizing the management of the Carlsbad Project but also making charges of a personal nature against [Reed]." Among other things, Tracy felt that construction had progressed too slowly, and that the lack of rehabilitation work on McMillan Dam was keeping the level of service too low. That same month C.H. McLenathen, Tracy's business partner, submitted a letter to the Secretary of the Interior and personally visited the Reclamation Service Director. Both communications listed a variety of allegations of mismanagement by the Reclamation Service workers at Carlsbad. These complaints generated only minor official repercussions, but they were a substantial annoyance to Reed, who felt that the complaints did not reflect reality but rather that "Mr. Tracy and his partner, Mr. McLenathen, are making a great hullabaloo in order to further their own interests." [6]

|

| The U.S. Reclamation Service replaced the damaged headgates at McMillan Dam in September 1908. — Fred Quivik, February 1990. |

Although McLenathen and Tracy operated a real estate business in the Carlsbad area, in all likelihood the primary "interests" to which Reed referred involved Tracy's long-standing relationship with the largely moribund Pecos Irrigation Company. At the time the Reclamation Service purchased the irrigation company's physical plant in 1905, the company owned some 30,000 acres of potentially irrigable land within the boundaries of the Carlsbad Project. [7] After the sale was consummated, Tracy consistently maintained that the Pecos Irrigation Company had only accepted the government's low price because the Reclamation Service had implied that water would be provided to the company's lands. This would have substantially increased the market value of the company's property, and allowed it to evolve into a profitable real estate sales organization. Unfortunately for Tracy, however, the Carlsbad Project's 20,000-acre capacity meant that most of the company's lands did not receive irrigation water, although they were within reach of the system's canals. Supplying water to the company's lands hinged on the construction of Reservoir No. 3 and the consequent expansion of the project's total capacity. It was not surprising, then, that Tracy was a consistent and vocal supporter of proposals to enlarge the Carlsbad Project.

As Tracy and the irrigation company began to realize that such expansion was not immediately forthcoming, a search began for alternative opportunities for the disposal of company land. One such opportunity soon presented itself in the form of the Malaga Land and Improvement Company. The Malaga company held several thousand acres of agricultural land near the southern edge of the Carlsbad Project; at least 5,000 acres of this land had been acquired from the Pecos Irrigation Company. [8] By 1908, the Malaga company was engaged in selling real estate through the mail, offering a five-acre "truck farm" and a lot in the tiny townsite of Malaga for $150.00, payable on time. Although the Malaga land was not receiving Carlsbad Project water, the company's glowing brochures were carefully worded to imply that such water was soon forthcoming; this, however, was not the case. Tracy and McLenathen were among the local citizens listed as references in the brochures. [9]

By April 1908, the Reclamation Service was receiving letters from Malaga customers complaining of the Malaga Company's alleged fraud. The company's promotions generated substantial concern within the Reclamation Service; McLenathen, Tracy, and others soon began receiving unhappy letters from Reclamation Service officials. Tracy responded with a rambling, typically angry, 15-page letter denying that the Malaga Company was working to "defraud certain of our weak-minded fellow citizens whom it is [the Reclamation Service's] duty to protect." [10] The company's land sales apparently continued unabated, despite recurring complaints. In one instance, a particularly vocal Malaga "victim" was sued by the company for defamation. [11] The exact level of Tracy and McLenathen's involvement in the Malaga company remains unknown, however.

|

| The five headgates at McMillan Dam were lifted by ball-bearing gate stands. — Bureau of Reclamation, Salt Lake City, ca. 1908. |

The 1908 growing season saw the completion and opening of most of the remaining portions of the Carlsbad Project's irrigation network. The Reclamation Service was able to provide water to some 7,500 acres that year, an improvement over 1907 but still substantially less than the roughly 13,000 acres served by the Pecos Irrigation Company. Tracy blamed the shortfall on the Reclamation Service's failure to store winter runoff in project reservoirs and their failure to begin repair work on McMillan Dam. He bemoaned the losses caused by year after year of drought, with "orchards, vineyards, shade trees killed till the heart was sick." [12] He claimed that "the proper use of McMillan and Avalon" would have allowed the Reclamation Service to immediately irrigate 30,000 acres of project land. [13]

|

| The U. S. Reclamation Service constructed a 4,000-foot-long east embankment to prevent water from spreading into a porous portion of McMillan Reservoir. — Lon Johnson, February 1990. |

Reclamation Service engineers finally turned their attention to troubled McMillan Dam in September 1908. That winter, the rotting headgates were replaced, and spillway and diking work were completed. The McMillan complex also received a new "East Embankment;" this consisted of a 4,000-foot-long dike designed to block off a large gypsum deposit along the reservoir's eastern shore. This deposit was believed responsible for much of the seepage which had plagued McMillan throughout its history. Construction work during 1908-09 also included lining portions of the canal system which were suffering unusually high seepage rates. [14]

As the Reclamation Service completed its initial rehabilitation efforts and restored water to more and more of the project's lands, the issue of fee payments by landowners remained unresolved. Although the Secretary of the Interior had agreed to postpone the due date of the 1908 construction assessment, this relief was partially negated by the poor crop yields experienced that year. Simultaneously, the landowners' financial obligations were increased by a small additional assessment to cover the 1908-1909 construction work at McMillan. For the year 1909, each acre of irrigable land was assessed a "construction fee" of $3.10; additional, smaller charges were levied to pay for the system's annual operating and maintenance costs. That November, the landowners petitioned the Secretary of the Interior for relief from the fee assessments, noting:

The shareholders are anxious and willing to pay all legal charges assessed against them and they recognize this as a legal and just charge. . . . [However,] of the old timers most of them were nearly mined by being three years without water for irrigation, and the new settlers have spent their ready money in expenditures incident to the establishment of a home in a new country. [15]

|

As an alternative, the water users proposed replacing the flat-fee annual construction assessments with a graduated system. Under such a scheme, the annual construction levy would initially be relatively low, increasing in later years as the lands became more fully developed and, hopefully, more profitable. The group suggested a construction assessment of $1.00 per acre the first year, gradually increasing to $5.00 per acre in the tenth and final year. [16] (The Reclamation Act specified that a project's construction costs be repaid to the Federal government over a ten-year period.)

In November 1909, the Department of the Interior expressed an implied recognition of the farmers' dilemma by postponing any possible forfeiture actions until March 31, 1910. As that deadline approached, the Reclamation Service noted a continued uncertainty regarding the landowners' ability to pay, "as misfortune has again overtaken the farmers and what is known as root rot has invaded this section. . ." [17] By late March 1910, the water users association had collected only $15,000 of the approximately $60,000 in annual assessments that were due that year. Nevertheless, local Reclamation Service staff counseled against the granting of further payment extensions, while still displaying leniency in individual cases showing unusual hardship. The Reclamation Service director concurred. [18]

This was not a true resolution of the issue, however, and landowners continued to ask for more substantive relief as the number and amount of delinquent assessments increased. The graduated-payments proposal remained alive; Reed approved of the concept, calling it "conducive to the greatest prosperity." [19] By early 1911, however, the water users association had supplanted its earlier proposal with a campaign to divide the nine remaining construction assessments into eighteen annual installments, while simultaneously postponing the due date of the 1911 assessment. [20] Although Reclamation Service engineers seemed to recognize the reality of the problem, the delinquency situation was generally downplayed and blamed on individual farmers rather than on the fee system itself. Federal observers seldom mentioned the fact that the project's farmers had been without water during the system's reconstruction. After examining the circumstances of individual delinquencies, Reed noted that some farmers could afford to pay but simply had not, that others were "old-timers [who] never have and probably never will make a success at farming," and that at least one delinquent young man "cultivated his appetite for booze to a much greater extent than he has his acres." [21]

Despite Reed's analysis, it was soon apparent to the Reclamation Service that the worsening delinquency situation could not be cured by simply postponing annual assessment due dates. By March 1911, only 99 of the 461 construction assessments for the year 1909 had been collected, and only 4 of the 1910 assessments had been received. Many of the farmers who had paid their assessments had borrowed against future crops to do so. In February 1911, Congress authorized temporary relief by allowing the Reclamation Service to suspend enforcement of overdue irrigation assessments pending restructuring of the debt, and debt enforcement at Carlsbad was suspended on March 13. [22] The assessment schedule was reevaluated over the following eleven months, and a restructured fee system was unveiled in February 1912. The new plan called for an increase in the total per-acre assessment to $45.00, with the additional funds going toward "betterments" for the system (including the repair of 1911 flood damage and the lining of some canals to reduce seepage). The concept of graduated fee payments was also adopted; the charge was set at $1.00 per acre the first year, rising to $6.00 per acre for the eighth, ninth, and tenth years. [23]

The 1911 Flood Avalon's Cylinder Gates

Despite the obvious financial difficulties of the Carlsbad Project and its farmers, Tracy and his supporters continued to push for the system's enlargement. They also continued to complain loudly about the Reclamation Service's supposed local mismanagement. Tracy's unhappiness was dramatically displayed following a July 1911 flash flood which washed out small portions of the east and west McMillan embankments and significantly damaged two of the Avalon spillways. After hearing of the damage and failing to obtain satisfaction through his normal channels, Tracy fired off a telegram to the White House, rhetorically asking President William Howard Taft:

. . . if there is no redress or relief or adequate appeal for settlers from idiotic incompetence of reclamation service [sic]. Carlsbad project is now suffering from stupid obstinacy of Arthur P. Davis and W.M. Reed. . . [who are employing] underground methods to provide for our people raising the fund to repair and conceal results of [their] incompetence. . . [24]

Implying that a local reenactment of the disastrous Hondo Project was in the works, Tracy asked Taft to send an outside observer "with brains" to evaluate the situation. His request was apparently never taken up, however, and the Reclamation Service assured the executive branch that the flood was not a major setback. [25]

The effects of the flood did, however, substantially reduce the project's capability to store the upcoming winter's runoff for future irrigation use, and Reed immediately authorized a "force account" repair effort which continued throughout the winter of 1911-1912. The reconstruction, funded with a $50,000 supplemental Reclamation Service allocation, repaired the most significant damage at McMillan and elsewhere. [26] The first repairs, however, failed to address one of the system's largest problems: the troubled Avalon Dam and its damaged spillways. That fall, the Reclamation Service dispatched a board of engineers to survey Avalon and provide recommendations for needed improvements. The board's report, issued December 7, 1911, recommended major reconstruction of both damaged Avalon spillways, smaller-scale remodeling at the third Avalon spillway, and improvements to the embankments at both Avalon and McMillan Dams. [27]

The 1908 primary spillways at Avalon had been a significant source of unhappiness to Tracy. When his letter to the President generated an inquiry from the Secretary of the Interior, Tracy responded claiming that the water users association had recognized the "insufficiency" of design of the then-new "automatic" gates in Avalon's Spillway No. 1 as early as 1908. Tracy claimed that the spillway's design was unworkable, noting that the gates had failed to operate properly during the flood and that mules were finally needed to open them. Few primary sources describing the design or operation of these spillway gates survive today, although a letter from Tracy to the Secretary of the Interior supplies one contemporary description, supported by a period construction drawing:

. . . the gates are double, two gates to each of 39 openings ten feet high. They were tied together in pairs, one opening up stream being fastened by cable in such fashion to the one in the next space, opening down stream, that the pressure of the water was expected, by what kind of witchery I know not, both to open the gates when the latches were loosened and to close them again when the operator so willed. It was soon found that they would close fast enough to seriously damage them whenever it was tried; but no power on earth could keep them open in a real flood. [28]

In his letter, Tracy seemed satisfied that the 1908 spillway would operate satisfactorily with the removal of the upstream set of gates, thereby obviating the need for a more expensive design solution that was already in the planning phase. [29]

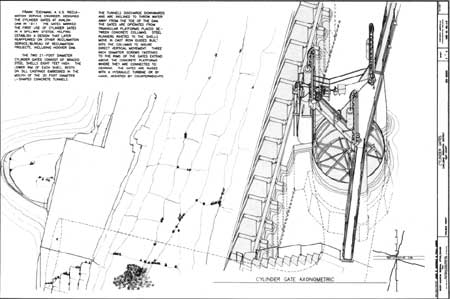

Portions of the Reclamation Service's 1911 Avalon projects were designed by Frank Teichman, a Reclamation Service engineer based in El Paso who had designed gates and valves for various Reclamation Service projects. Born in Germany in 1853 and educated in engineering in Dresden and Vienna, Teichman emigrated to the United States in 1882. After three years as a draftsman in New York, he moved to California where he worked as an engineer for both railroad and reclamation projects. He began working for the Reclamation Service in 1904 and was one of the designing engineers for Roosevelt Dam in Arizona. [30]

|

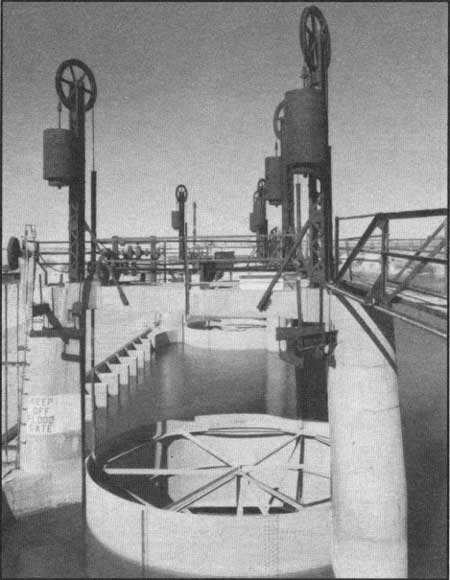

| In 1911, two technologically innovative cylinder gates replaced the "automatic" gates in Avalon Dam's Spillway Number 1. The replacement occurred after the automatic gates failed to open during a Pecos River flood and the dam tender was forced to bring in mules to manually open the old gates. — Fred Quivik, February 1990. |

Teichman's plans for Avalon included a dramatic circular concrete overfall dam to be located at Spillway No. 2. D.C. Henry, consulting engineer with the Reclamation Service in Portland, Oregon, provided design guidance. Spillway No. 2 was a remnant of the old Pecos Irrigation Company infrastructure; the spillway had been largely washed out by the 1911 flood. Teichman's replacement overfall structure had a crest some 393 feet long displaying, in plan, a full quarter-circle of curvature. The overfall's eastern half was a concrete curtain wall displaying an ogee section, while the dam's western half featured a stepped concrete wall almost resembling a giant amphitheater. The steps protected a formation of caliche, a carbonate-enriched soil found in arid and semiarid climates.

|

| When the cylinder gates were lifted, two concrete tunnels discharged water to an overflow area, eventually leading back to the old Pecos riverbed. — Fred Quivik, February 1990. |

More technically impressive, however, were the cylinder gate outlet works Teichman designed for Avalon. The cylinder gate design originated in navigation canals, where they were called cylindrical valves and were used to fill or empty locks of water. Such valves were an important part of the design for the Panama Canal, and had seen wide use in the United States prior to that. Cylindrical valves displayed a technical`advantage over traditional sliding gate valves in that water pressure was exerted against the cylindrical valves equally from all directions; this meant that resistance to opening and closing the valves did not increase with head. The Panama Canal's cylindrical valves were 7 feet, 1 inch in diameter and operated by means of a single, central valve stem. [31]

The first use of a cylinder gate by the Reclamation Service was on the Yuma Project on the Colorado River in Arizona and California. As originally planned, the Yuma Project was to have a main canal entirely on the Arizona side of the river, supplying water to lands south of Yuma. However, the technical difficulties inherent in a canal crossing of Arizona's erratic, unpredictable Gila River prompted Reclamation Service engineers to move the canal's upper reaches to the California side of the Colorado River. The canal would then utilize a siphon to cross the Colorado near Yuma. Construction of a siphon suggested additional technical problems: the excavation and tunnelling involved would require working in shifting sand using compressed air. During planning, the Reclamation Service corresponded with engineers and contractors in Chicago, Boston, and New York, seeking both design assistance and construction equipment suited to the task. In the midst of these technical discussions and with little fanfare, Teichman designed a cylinder gate 21 feet in diameter for the intake to the siphon. Such a gate was ideally suited to the project because the seat for the cylinder could be the same circular shape as the intake shaft. Unlike the cylinder valves used on the Panama Canal, Teichman's design for the Colorado River siphon used three threaded stems attached to the perimeter of the cylinder and driven by an electric motor to raise and lower the gate. [32]

|

| Because Avalon Dam was without electricity, Teichman designed heavy counterbalances to assist in raising the 15,400-pound cylinder gates. — Fred Quivik, February 1990. |

Drawing on his experiences with the Yuma project, Teichman designed a new spillway for Avalon which incorporated the cylinder gate concept. The plan specified two vertical cylinder gates which, when closed, maintained a spillway crest similar to the reservoir's other overflow spillways. When raised, however, they permitted the rapid lowering of the reservoir in advance of anticipated flood waters; this reduced the danger of Pecos floodwaters overtaxing Avalon's overflow spillways.

Teichman's plan located the two cylinder spill gates over downward-discharging tunnels in the headworks channel. (The openings for the former gates along the crest of the spillway were filled with concrete.) The new gates were 21 feet in diameter, consisting of braced steel shells 8 feet high. The upper rims of the shells were just above the spillway crest, while the lower rims rested on sills embedded in the mouths of L shaped concrete tunnels 20 feet in diameter. Each tunnel tapered to an elbow transition to a horizontal tunnel which carried the water away from the base of the dam. Because Avalon was without electricity, counterbalances were added to the hoist mechanisms so that each 15,400-pound gate could be hoisted by the operator with a hand-crank. To make the operator's job easier, Teichman equipped each gate with a small water-driven turbine to power the hoist under normal conditions. [33]

By the end of September 1911, Teichman had completed his design for the cylinder gates and recommended their immediate purchase. A series of telegrams between Louis C. Hill, the Reclamation Service's supervising engineer at Carlsbad, and W.M. Reed, by this time the district engineer for the Reclamation Service in El Paso, finally resulted in a roundabout approval to purchase the gates with neither man apparently wanting to take ultimate responsibility. This foreshadowed several months of bureaucratic correspondence among Reclamation Service officials, including a statement by the chief engineer that challenged Reed's authority to purchase the gates and questioned the efficacy of the design and the proposed location. The December board of engineer's report, however, finally indicated the Reclamation Service's official approval of Teichman's design. [34]

|

| When tested in November of 1912, the new cylinder gates operated successfully. The Bureau of Reclamation incorporated similar gates in other Federal dams, including the intake towers of Hoover Dam. — Denver Branch, National Archives, Denver, Colorado; February 15, 1912. |

Work on the cylinder gates proceeded throughout early 1912. They operated successfully under limited testing that June, but it was not until late November that the Reclamation Service operated the gates to full capacity. The Reclamation Service invited some of the gate's more vocal local critics to observe the tests. Much to the delight of Hill, and presumably Teichman who was also present, the gates performed "satisfactorily" with only minor problems. [35]

Following the successful implementation of the cylinder gate design at Avalon, Teichman continued to design cylinder gates for other Reclamation Service projects. Elephant Butte Dam (1912-16) on the Rio Grande Project in southwestern New Mexico was a notable example. The dam's spillway features four cylinder gates, each ten feet in diameter. As at Avalon, these gates were designed to allow operators to begin spilling in advance of water overtopping the crest of the spillway. The Franklin Canal on the Rio Grande Project utilized additional cylinder gates for "drops" (structures for facilitating sudden elevation change in a canal). These gates were only about five feet in diameter and could be lifted with a hand-operated winch.

|

| The new cylinder gates were 21 feet in diameter, consisting of braced steel shells eight feet high. Denver Branch, National Archives, Denver, Colorado; January 1912. |

By the time Elephant Butte Dam was completed, Teichman had moved to Washington, D.C. to head the Technical Section of the Reclamation Service. During the 1910s and 1920s, the Reclamation Service showed a decided preference for cylinder gates, as well as radial gates, for relatively small applications where ease of operation was important. At Sherburne Dam in Montana (1921), cylinder gates were used for the outlet works. These gates were atop shafts, similar to the Colorado River siphon application, but in this case the shafts were concrete outlet towers which conveyed water to conduits under the dam. [36]

The Sherburne project was a precursor to the Bureau of Reclamation's most spectacular use of cylinder gates: the intake towers at Hoover (Boulder) Dam. Hoover Dam's cylinder gates are housed in four 390-foot-high intake towers with two 32-foot diameter gates per tower, one at the base and one near the midpoint. Electric motors in the tops of the towers lift the gates by means of screw stems. At their completion, the towers were visually stunning features in the empty reservoir area; much of the towers were soon obscured by water, however, leaving little hint of the structures' relationship to the cylinder gates at Avalon. Hoover's cylinder gates reflect the Bureau of Reclamation's preference during the 1930s to use cylinder gates in intake towers and outlet works, rather than spillways. [37]

Despite the fact that cylinder gate designs saw significant Reclamation Service use both before and after Avalon Dam, Avalon's cylinder gates are unique among these projects for their particular adaptation to the circumstances, with counter-balanced hoisting works driven by water-powered turbines. Teichman's Avalon designs reflected innovative design solutions to local engineering problems. They remain among the most visually striking features of Avalon Dam today.

Endnotes

1. W.M. Reed to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, October 18, 1907, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 438, File 338-A, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

2. See, for example, F.E. Bryant's editorial, "Uncle Sam Is A Water Hog," Field and Farm [Denver, Colorado], February 29, 1908.

3. A.P. Davis to the Secretary of the Interior, October 6, 1910, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 438, File 338-A, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

4. Francis G. Tracy to James R. Garfield, December 30, 1907; James R. Garfield to Francis G. Tracy, January 9, 1908, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 438, File 338-A1, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

5. Louis C. Hill to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, November 21, 1908, ibid.

6. W.M. Reed to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, June 24, 1908; Louis C. Hill to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, June 30, 1908; Director, U.S. Reclamation Service to L.C. Hill, June 10, 1908, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 441, File 466, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

7. J.J. Hagerman, "In the Matter of the Hondo Reservoir," transcript of testimony given against building the Hondo Reservoir, September 6, 1904, 27, RG 115, Entry 4, Box 1, File 25, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

8. Information concerning the relationship between the Pecos Irrigation Company and the Malaga Land Company is contained in a deposition by Tracy attached to a letter from W.M. Reed to the Chief Engineer, U.S. Reclamation Service, November 17, 1908, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 442, File 466-4, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

9. Descriptions and a sample of the Malaga Land Company brochures, ibid.

10. Francis G. Tracy to Morris Bien, June 9, 1908, ibid.

11. W.M. Reed to the Chief Engineer, U.S. Reclamation Service, November 17, 1908, ibid.

12. Francis G. Tracy to Morris Bien, June 9, 1908, ibid.

14. "History of Carlsbad Project — 1912."

15. Pecos Water Users' Association to R.A. Ballinger, November 29, 1909, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 438, File 338-Al, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

17. Director, U.S. Reclamation Service to the Secretary of the Interior, March 22, 1910, ibid.

19. W.M. Reed to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, March 5, 1910, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 439, File 338-A4, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

20. Pecos Water Users' Association to the Secretary of the Interior, March 1, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 438, File 338-Al, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

21. W.M. Reed to L.C. Hill, April 15, 1910, ibid.

22. Director, U.S. Reclamation Service to the Secretary of the Interior, March 13, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 438, File 338-A, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

23. F.H. Newell to the Secretary of the Interior, February 13, 1912, ibid.

24. Francis G. Tracy to the President (telegram), September 9, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 441, File 466, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

26. W.M. Reed to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, October 27, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 437, File 331; F.H. Newell to Louis C. Hill, December 16, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 443, File 651, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

27. D.C. Henny and Louis C. Hill to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, December 7, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 443, File 651, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

28. Francis G. Tracy to the Secretary of the Interior, September 23, 1911, Pecos Valley Projects Office, Bureau of Reclamation, Carlsbad, New Mexico.

30. John William Leonard, Who's Who In Engineering (New York: Who's Who Publications, Inc., 1925), 2061.

31. H.F. Hodges, "General Design of the Locks, Dams, and Regulating Works of the Panama Canal," 10, and L.D. Cornish, "Design of the Lock Walls and Valves of the Panama Canal," 83-84, both in George W. Goethals, ed., The Panama Canal: An Engineering Treatise (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1916).

32. Board of Engineers to Director, April 11, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 1094, File 241, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Francis L. Sellew, "The Colorado Siphon at Yuma, Arizona," Engineering News 68 (29 August 1912): 377-385.

33. F. Teichman to the Director, U.S. Reclamation Service, November 3, 1911; W.M. Reed to the Director, November 16, 1911; F. Teichman to W.M. Reed November 16, 1911; W.M. Reed to the Director December 27, 1911, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 443, File 651, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

34. For the telegrams between Reed and Hill, see Bureau of Reclamation, General Correspondence Files of the Office of the Chief Engineer, RG 115, Box 269, File 77G. National Archives, Denver, Colorado. For the extensive correspondence between the local and district engineers and the USRS, Washington, D.C., see RG 115, Entry 3, Box 443, File 651, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

35. Assistant Engineer McIntyre to District Engineer, June 29, 1912, General Correspondence Files, Office of the Chief Engineer, Records of the Bureau of Reclamation, RG 115, Box 269, File 77G. National Archives, Denver, Colorado; Louis C. Hill to Chief Engineer, January 14, 1913, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 442, File 351, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

36. "Valves, Gates, and Steel Conduits," Design Standards Handbook No. 7 (Washington: Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, 1956), file in the basement of the Central Snake Projects Office, Boise; Wesley R. Nelson, "Construction of the Boulder Dam," The Story of Boulder Dam, reprints of articles from Compressed Air Magazine, 1931-1935 (Las Vegas: Nevada Publications, n.d.), 138.

37. Davis, Irrigation Works Constructed by the United States Government, 240-241, 252-253; Bureau of Reclamation, Reclamation Project Data (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1941), 189, 193, 369, 371; Director and Chief Engineer to District Engineer Office, March 11, 1915, RG 115, Entry 3, Box 291, Files 910-12, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

rmr/0/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2008