|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 1:

INTRODUCTION

Management Summary

The purpose of this Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) is to identify the landscape characteristics and features that contribute to Golden Spike National Historic Site (NHS) and to make recommendations regarding the long-term preservation and management of the site. Several planning documents have been prepared for Golden Spike NHS that outline the management and interpretive goals for the site. For the most part, these goals have been expressed in general terms, and not within the context of landscape treatment recommendations. However, the stated goals do outline the interpretive intent for this park service unit.

The park's 1978 General Management Plan (GMP) identifies the management objectives for Golden Spike NHS. The goals that are specifically relevant to this analysis include the following:

To manage the park's historic scene and resources, as closely as practical, in keeping with their character and appearance in 1869.

To support preservation and restoration of the site through identification, evaluation, and interpretation of historic resources.

To provide visitors with an opportunity to understand and appreciate the railroad race to Promontory, and the effects of its completion on the development of the West, and on the social, political, and economic history of the nation.

More recent park planning documents include the Strategic Plan and Comprehensive Interpretive Plan, prepared in 1997 and updated in 2000, and the Resource Management Plan updated in 1999. All three of these plans restate the need to protect, maintain and, in some instances, restore the natural and cultural resources that contribute to one's understanding of the construction of the transcontinental railroad. Further, the Comprehensive Interpretive Plan reaffirms the long-standing temporal focus for interpretation at Golden Spike NHS: "... the Last Spike Site will be presented to recreate the May 10, 1869 scene in so far as possible." (National Park Service 1997a:24). The plan states that the focus of interpretive effort for the area within one mile either side of the Last Spike Site will be May 10, 1869. The focus of resource management activities at the summit continues to be preservation of the remaining archaeological evidence of the town of Promontory Station and of the operation and maintenance of the railroad.

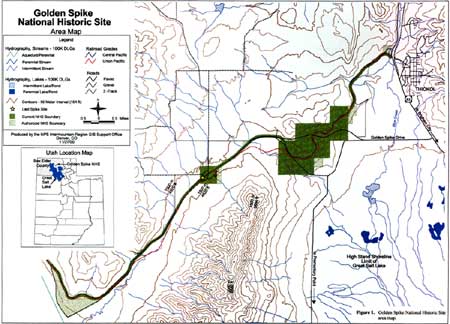

Figure 1 shows the location of Golden Spike National Historic Site including its existing and authorized boundaries.

|

| Figure 1. Golden Spike National Historic Site area map. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Historical Summary

The history of the landscape at Promontory Summit in northern Utah links inextricably to the history of building and operating the first transcontinental railroad across the United States. Constructed between 1863 and 1869 by the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad companies, the two rails advanced from the west and the east and met at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869. Ceremonies held that day at the summit marked the achievement by driving the last spike and by sending the news over the simultaneously built telegraph line across a rapt nation. Because no junction point was specifically stipulated in the sponsoring legislation, survey and grading crews had done their work well beyond the eventual meeting point. For a distance exceeding 200 miles crews intermittently built a parallel grade east and west of the summit. Portions of this parallel grade are still evident at the summit and testify to the archly competitive nature of the enterprise.

A plan for building a transcontinental railroad was first presented to Congress by New York merchant Asa Whitney in the 1840s. In 1853, seeking to determine the most practicable and economical route, Congress appropriated funding for five surveys. The selection of a transcontinental route, however, was plagued by political intransigence in Congress over the issue of slavery and the question of where it might extend as the country developed westward. After the secession of the South and the outbreak of the Civil War, Congress passed legislation in 1862, amending it in 1864 and 1866, to provide for the construction of the first transcontinental railroad and chartering the Union Pacific Railroad Company to help build it. This company and the privately incorporated Central Pacific were together responsible for building the Pacific Railroad. Federal assistance included 30-year government bonds at 6 percent interest and grants of land along the route. Bonds were issued at varying rates depending on the ruggedness of the terrain: $16,000 per level mile; $32,000 per mile in the foothills; and $48,000 in the mountains. Racing to meet the end of the other company's line, each sought to construct the greater portion of the road and thereby acquire more land and loans.

The Central Pacific, whose labor force consisted primarily of Chinese workers supplemented by Irish and Cornish crews as well as Paiute and Washo Indians, almost immediately faced the challenge of blasting through the granite walls of the Sierra on the California-Nevada border. The Union Pacific, on the other hand, did not encounter heavy grading work until it reached Wyoming and Utah. In addition to many Irish laborers, Germans, Englishmen, freed Blacks and American Indians also worked for the Union Pacific. Mormon crews worked for both railroad companies once the lines pushed into the bounds of Utah Territory.

By February, 1869, Central Pacific grading crews had begun the difficult work on the east slope of Promontory Summit, including work on the Big Fill at a ravine located about halfway up the slope. The Union Pacific track reached Ogden by March 8, and 20 days later the company initiated construction of its Big Trestle located some 150 feet east of, and parallel to, the Big Fill. By early April, the Central Pacific track was approaching Monument Point, while on April 8 the Union Pacific's track reached Corinne — one of the infamous Union Pacific "Hell-on-wheels" towns that attracted the seamier side of business at these end-of-track locations. On April 10, by a joint resolution, Congress designated Promontory Summit as the meeting place, confirming a decision reached by the two companies the day before. The Central Pacific Railroad Company also agreed to buy the Union Pacific's track between Promontory Summit and a point 5 miles west of Ogden, leasing the remaining 5 miles from the Union Pacific for a term of 999 years.

During the months of April and May, 1869, the east and west slopes of the Promontories teemed with life in hundreds of railroad construction camps as graders, trestle-builders, and track-layers worked feverishly to complete the rail line. Archaeological evidence of these temporary camps has been found on the summit. By the end of April, the Central Pacific had completed its Big Fill, had laid 10 miles of track in one day (April 28), and on April 30, the Central Pacific's track reached the summit at Promontory. On May 5, the Union Pacific crews finished the Big Trestle and Carmichael's Cut. Between May 6 and May 9, Union Pacific workers completed the remaining rock cuts, built a 2,500-foot siding and a "wye" at the summit, and laid track to within a rail's length of the Central Pacific's track.

On May 10, 1869, officers of both companies as well as a host of others celebrated the laying of the last rail and the driving of the last spike in a ceremony at mid-day. The joining of the rails at Promontory Summit signified the end of a colossal effort to build the first transcontinental railroad in only six and one half years, less than half the time that Congress had specified. Representing one of the greatest engineering feats of the nineteenth century, completion of this continuous rail line accelerated the settlement and economic development of the American West, spelling the ultimate doom of the American Indians' traditional way of life. Completing the first transcontinental railroad also facilitated transportation and commerce, improved communications, and helped unite the country physically, economically and politically.

Until December of 1869, when the Central Pacific acquired the Union Pacific line to Ogden, which then became the terminus, some 30 establishments — large canvas tents, some with wooden storefronts — served passengers waiting to change trains at the summit. From 1870 to 1904, Promontory was a maintenance station for the railroad. Buildings associated with its railroad functions included a freight depot, a roundhouse, a section house, a water tank, tool sheds, and bunk houses for railroad workers. By 1870, the Central Pacific had improved the track on the east slope between the vicinity of the Blue Creek drainage crossing and Promontory Station, abandoning portions of the Union Pacific's line and building new track on the Central Pacific grade.

After the Lucin cutoff rerouted cross-country traffic to the south of Promontory in 1904, mixed (passenger and freight) local trains continued to cross the summit until 1942 when rails on the Promontory Branch were pulled for defense needs. Although quieter, with fewer trains using the station, the town of Promontory continued to serve as a community center. Ranching and dry-farming provided the area's economic base. The open, sparsely populated landscape at the summit reflected this rural economy.

Although the Southern Pacific Railroad had earlier placed a monument at the summit to honor the joining of the rails there, federal recognition of the significance of the site dates from 1957 when Interior Secretary Fred Seaton designated a 7-acre tract of land in non-federal ownership at the summit as a national historic site. In 1965, Congress passed legislation to create the Golden Spike National Historic Site in order to commemorate the completion of the first transcontinental railroad. By purchasing and exchanging lands the Interior Department acquired 2,176 acres for the site. The 1965 legislation also appropriated over $1 million for site development, which was used to build a visitor center, to provide parking areas and other facilities, and to develop interpretive exhibits. In 1976, Congress increased the appropriation to over $5 million. Finally, in 1980, Congress amended the boundaries of the site, increasing its acreage to 2,735.28 acres, including 532.08 acres that remain in non-federal ownership. Since 1965, relying on pieces of the story of the building and operating of the first transcontinental railroad that remain visible within this landscape, the National Park Service has managed the resources at the site for their interpretive potential and commemorative value.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr1.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003