|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 2:

SITE HISTORY (continued)

Southern Pacific's Efforts to Abandon the Promontory Branch and the "Undriving" of the Last Spike

Initially, in April 1933, contending that there simply was not enough business on the line, Southern Pacific sought permission from the federal Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to abandon the western end of the line between Kelton and Lucin. Over a year later, in June of 1934, the ICC denied this application, ruling that the slight potential savings to the railroad company did not justify the inconvenience to shippers that would result from abandoning this portion of the branch. Southern Pacific again tried to close this segment of the railroad in December of that year, still arguing that there was not enough business to warrant running any trains over this 55-mile stretch of the road. The ICC denied this application for reconsideration in March of 1936, for the same reason that it had denied the original attempt. Trying a different approach, the SP next sought permission from the Utah Public Service Commission, which ruled in March of 1937, that the company could discontinue all trains on the westernmost 20 miles of the line (Strack 1997:48-50).

Some five years later, on June 11, 1942, after the United States had entered World War II, the ICC finally approved Southern Pacific's request to abandon 123 miles of the remaining Promontory Branch line. This decision followed an April 22, 1942 request from the War Department for help from the Southern Pacific in obtaining old rails for defense purposes. The War Department had, in fact, specifically inquired about the "very rarely used" rail of the Promontory Branch (Strack 1997:50).

During the summer of 1942, beginning on July 1 and finishing during the first week of September, a Chicago firm — the Hyman-Michaels Company — pulled the rail along the Promontory line, starting at a spot 4 miles west of Corinne. At a rate of roughly 3 miles a day, two engines moved track-pulling equipment that lifted and loaded the old rails onto flat cars. An 8-man crew operated the block-and-tackle hoist that was mounted on a wooden frame at the end of a flat car. Because of the danger of ground fires caused when the locomotives sparked fires in the vegetation along the right-of-way, workers also had to dig fire breaks in order to protect the thousands of acres of wheat then growing on either side of the Promontory line (Mann 1969:131). Providing sorely needed wartime rails for tracks at military installations, the pulled rails were subsequently reused for tracks at the Utah Quartermaster Depot in Ogden, at Hill Field, at the Clearfield Navy Supply Depot, and the Tooele Army Depot (all in Utah), and at another military base located in Hawthorne, Nevada (Mann 1969:131; Strack 1997:50).

To mark the occasion of the pulling of the last spike of the Promontory Branch, Utahns scheduled a ceremony for September 8, 1942. Among those in attendance were: Utah Governor Herbert Maw, representatives of both the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads, other state officials including the attorney general and secretary of state, military personnel, members of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Box Elder County officials, as well as ranchers and farmers from the area. Of special significance, Mary Ipsen, then 85, who as a young 12-year-old had also been part of the crowd that celebrated the driving of the golden spike on May 10, 1869, was able to attend (Mann 1969:131, 134).

Those who planned the "undriving" ceremony attempted to recreate many of the features of the "driving" celebration that had occurred some 73 years earlier. The weather even cooperated by bringing a similarly pleasant, clear day. At around noon, the Hyman-Michaels Company situated its two locomotives nose to nose at a rail length's distance. George Albert Smith, a member of the Council of Twelve Apostles of the LDS church, provided an invocation.

Mrs. Ralph Talbot, Jr., whose great-uncle had attended the 1869 ceremony and whose husband was the brigadier-general commanding the Utah Quartermaster Depot, then handed a claw bar to Governor Maw. He and others took turns removing the last spike, until Everett Michaels, vice-president of Hyman-Michaels, made the final pull (Mann 1969:134).

The closing of the Promontory Branch brought even quieter times to the summit. Circa 1950, the roof of the previously abandoned Houghton store caved in. The 1930s telegraph wires continued to hum until the late 1950s, when the Southern Pacific Company replaced the telegraph line with a cable laid along the new track over the Lucin Cutoff. Vandals destroyed parts of old wooden culverts and trestles; others took pieces of the remaining structures for souvenirs. The last of the section houses burned down during the 1960s. But every year for twenty years before Congress voted to create the Golden Spike National Historic Site in 1965, the Golden Spike Association of Box Elder County, Utah, celebrated the joining of the rails at Promontory by re-enacting the May 10, 1869 ceremony. In this way the local organization helped to keep alive the memory of the historic race to complete the first transcontinental railroad.

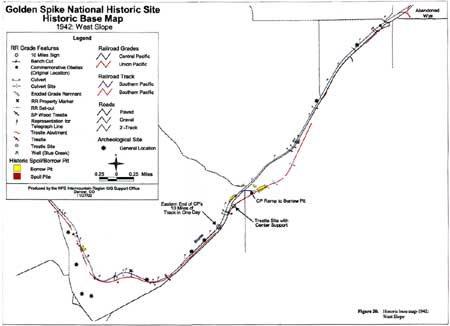

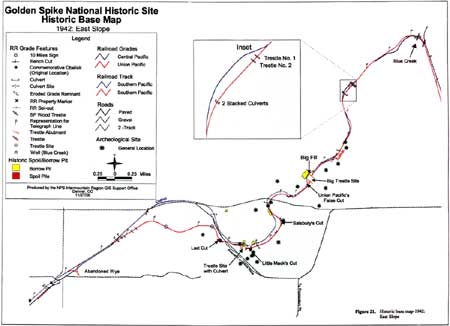

Figures 20 and 21 show the conditions on the west and east slopes of the NHS in 1942.

|

| Figure 20. Historic Base Map—1942: West Slope. |

|

| Figure 21. Historic Base Map—1942: East Slope. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr2k.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003