|

Western Museum Laboratories Navaho Life of Yesterday and Today |

|

Chapter XI:

CRAFTS

IMPORTANCE OF JEWELRY AND WEAVING The silver and turquoise jewelry, and the colorful woolen rugs created by the Navaho have made the name of this tribe a household word among the American people. Neither silversmithing nor the weaving of wool is old in Navaho history; both developed in post-Spanish times. In a short period, however, the Navaho transformed them from crafts into fine arts. That is more remarkable to artists is that the Navaho have made their arts economically successful. Weaving alone brings a million dollars into the tribe during a good year, and as nearly every household has a weaver or two, every part of the reservation shares in the income. The proceeds from the sale of silver ornaments are not so steady nor so evenly distributed because the silver workers are concentrated principally in the southern part of the reservation around Gallup, New Mexico, and other important stations on the Santa Fe Railway, where a tourist market exists.

All except the poorest Navaho own jewelry which, aside from its aesthetic and religious value, constitutes an investment comparable to our stocks, bonds, or diamonds. Fine blankets, too, are a form of wealth. Blankets are called "soft goods;" jewelry, "hard goods." Parents give their children jewelry of silver, turquoise, coral, and shell. By the time an individual is adult, he or she has a small fortune in ornaments to wear at fiestas and chants. Some of the jewelry is kept in pawn at a trading post, a trader acting as an easy going banker, who loans out money or groceries on the ornaments and waits a lifetime, if necessary, before selling the unredeemed items as "dead stock."

THEIR EARLY HISTORY The two arts did not develop contemporaneously among the Navaho. Weaving is almost two centuries older than silversmithing, for whereas the latter dates from about 1850, weaving began in the late seventeenth century, getting under way about the time of the Pueblo Rebellion of 1680. It is fairly certain that the Pueblos taught the Navaho to weave and that the Mexicans were their teachers in silver work. But according to a Navaho myth, it was two legendary beings, Spider Man and Spider Woman, who taught them to weave.

In the American Southwest the weaving of wool and silversmithing originated through Spanish influence, Coronado's arrival fixing 1540 as the earliest date for the beginning of the crafts. This point is particularly interesting because long before Europeans came to the New World, beautiful metal work and weaving, which rank with the finest in the world, were developed in northern and western South America and to a lesser extent in Central America. North of the Mexican region, however, the Indians were still in the Stone Age without a knowledge of metallurgy. Some of these Indians, like the mysterious mound builders of eastern America, did beat copper, meteoric iron ore, and gold into shape, but they did not have true metallurgy, which presumes a knowledge of the casting and smelting of metals.

The weaving done by the Indians north of Mexico was likewise more primitive than that of the South American Indians; still it did not lag as far behind as the metal work. Almost every tribe from the northwest coast of North America to the Southwest had weaving of a kind. Some areas produced beautifully designed blankets from the hair of bisons or mountain goats. Naturally such blankets were not common since one first had to catch the bison or the mountain goat--not an easy task with primitive weapons. Tribes with even a very simple culture knew how to prepare and plait rabbit skins into warm robes. The southwestern tribes, including the Navaho, also used yucca fiber and cedar bark to weave squares for crude blankets and clothing. The Pueblos even cultivated cotton and wove it on looms of the kind still used today by both Navaho and Pueblo weavers for wool. The Navaho did not raise cotton, nor are they known ever to have woven it, although Simpson (1852:79) vaguely mentions that the Navaho purchased Pueblo cotton, without stating whether or not it was already woven.

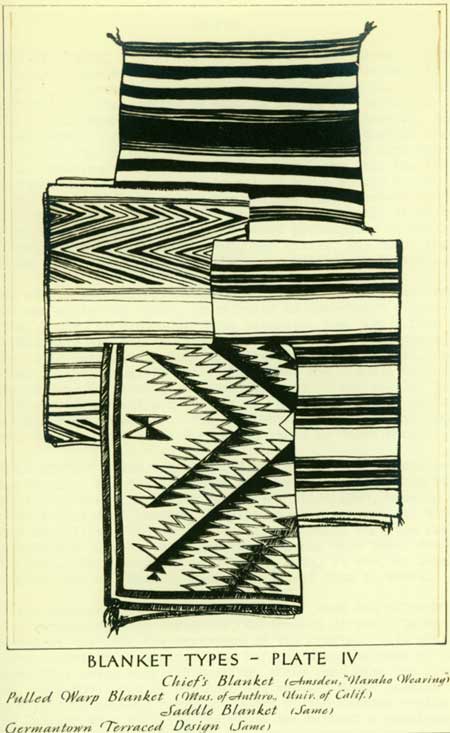

PLATE IV. BLANKET TYPES. Chief's Blanket (Amsden, "Navaho Weavings"). Pulled Warp Blanket (Mus. of Anthro., Univ. of Calif.). Saddle Blanket (Same). Germantown Terraced Design (Same). |

WEAVING

BEGINNING OF NAVAHO WEAVING When the Spanish came into the Southwest, lured by fantastic myths of the golden cities of Cibola, the Pueblo were doing fine work in cotton and creating delicate mosaics of turquoise. As the result of Spanish suggestion or tutelage, the Pueblos made their first attempts at weaving sheep wool. By 1680, when the Pueblos were gathering their forces in a final effort to oust their Spanish conquerors, the weaving of wool was well established as a tribal craft. Many of the Pueblo dwellers--we have already discussed the experiences of the Jemez--fled to the Navaho wilderness for refuge. It is believed that these refugees taught the Navaho to weave.

Amsden's masterly book, "Navaho Weaving," traces the history of this craft, which is also the history of the Navaho. Two paragraphs (p.133) summarize the development of weaving during the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries: "Of these four earliest known references to Navaho weaving (Spanish documents), each is more definite and emphatic than its predecessor. Croix in 1780 merely mentions the Navaho as weavers. Chacon in 1795 concedes them supremacy over the Spaniards in 'delicacy and taste' in weaving. Cortez in 1799 makes it clear that the production of blankets more than suffices for tribal needs. Pino in 1812 categorically places Navaho weaving at the head of the textile industry in three large provinces: significantly ahead even of the Pueblo craft, which mothered that of the Navaho.

"On abundant evidence, then, the Navaho had gained a recognized supremacy in native Southwestern weaving in wool as early as the opening of the 19th century; and down to the present day that supremacy has never been relinquished. The Hopi craftsman may have shown more conscience and conservatism at certain times, but the Navaho women have proved the more versatile, imaginative and progressive, and the Navaho blanket has always been the favored child of that odd marriage of the native American loom with the fleece of European sheep."

PERIODS OF WEAVING Amsden (p.223) distinguishes two definite cycles in the history of Navaho weaving: the intra-tribal or native, and the commercial or transition ("the era of the reservation and the trading post"). He states: "Each rested upon an economic basis and was molded by and to the needs of the time--for this is a craft, an industry, and like all such its existence depends on a human want." In addition to these two cycles, Amsden indicates that, although "this (second) phase is still (1934) in full vigor, yet there are signs of an impending readjustment to the changing times." This readjustment he calls the Revival, and dates it from 1920.

NATIVE PERIOD The native period dates from the beginning of Navaho weaving in wool, when they wove clothes and blankets for tribal use only, and continues until that time during the late eighteenth century when they began to weave for neighboring tribes and the Spanish. The weavers spun the natural, undyed sheep wool of black, gray, brown, and white and wove the yarn into designs of plain stripes of varying widths. The most characteristic product was a two-piece dress for women. Some of the finest weaving ever to be achieved by the Navaho women was produced in this intra-tribal period, when the weavers toiled only to satisfy their high standards of workmanship. Though they obtained their first weaving equipment and designs from their Pueblo teachers, the Navaho soon surpassed the Pueblos in quality of work. The Spanish began to seek Navaho women as slaves to weave for their households, and outlying tribes demanded blankets in trade.

THE COMMERCIAL PERIOD, which continues into the present, was thus begun. There are three major divisions of this period: the "Golden Age," characterized by the use of red bayeta; the Bosque Redondo and Reservation era; and the Revival.

THE GOLDEN AGE The reference of Cortez to trade in Navaho blankets shows that by 1799 the commercial period was well under way. Innovations developed, particularly in the use of colors and in such designs as depended largely on color for effect. The Navaho acquired indigo, their first commercial dye, from the Mexicans. The Spanish and Mexicans always had a variety of colors in their woolen materials, whereas the Pueblo weavers, who had pretty, vegetable dyes for cotton cloth, were quite conservative in dyeing their wool. The Navaho utilized the knowledge of dyes among their neighbors and experimented further with native plants to discover new dyes which might be adapted to wool.

From 1799 to 1863 the Navaho were prosperous and they spent these busy, successful years raiding, farming, herding, and weaving. During the early years of the Golden Age, the Spanish contributed one more item to the prosperity which they had indirectly brought to the Navaho. A common trade article of the time was flannel or baize, generally known in the Southwest by its Spanish name, bayeta. The Spaniards bought bayeta in England for trade purposes and for gifts to the Indians. It was made in many glorious colors, but so common and popular was red in the Southwest that red and bayeta have become synonymous to the lay person. About 1800 the Navaho obtained this flannel, which has a long nap on one surface, unraveled the cloth, respun the yarn into a single ply, and wove it into their blankets.

Of the influence of bayeta, Amsden writes (p.150): "The bayeta period marked the high point, the 'Golden Age' of Navaho weaving, for this rich fabric called forth the best in every phase of the craft--in spinning, dyeing, weaving, pattern creation. Only an expert could wed native wool and bayeta fiber in a harmonious and happy union. Only an artist could realize the full potentialities of such fine smooth wefts, such rich colorings, as bayeta afforded and inspired. And the Navaho woman responded to the stimulus, proved herself an expert and an artist--by grace of bayeta." (See Plate III, p.35.)

The Navaho now had red and blue, in addition to the natural colors of wool, and bayeta red, indigo blue, black, and white were predominant colors for wool. Striped designs continued in popularity, but achieved new interest through the use of red and blue. The conservative Pueblo weaver clung to stripes, but the Navaho craftswoman restlessly experimented with simple geometric patterns and color combinations. She developed the terraced design, which became the most characteristic form of the era between 1800 and 1863, just before Kit Carson put a stop to further progress.

The weavers still produced dresses and shirts for tribal use, but to satisfy trade demands they created new styles. Navaho blankets were worn by Indians and white people as far north as the northern Great Plains and as far west as the Pacific. Amsden (p.206) mentions an engraving of 1822 which shows Indians of the San Francisco Bay region wearing Navaho blankets. The most popular style of garment was the man's shoulder blanket, of which the chief's blanket, with its broad horizontal stripes of black, white, red, and sometimes blue, is a special type.

The poncho serape made abundant use of bayeta, and was bought by wealthy Spaniards and the Indians. Essentially it was a blanket, longer than wide, with a slit in the center to slide the garment over the head and around the shoulders. It was sometimes gathered closer to the body by a leather belt ornamented with silver discs, or by a woolen sash. Amsden states (p.103): "The serape, modified though it has been in many details, must be considered the universal type garment of the Navaho, the type that more than all others is behind the broad phrase of 'Indian blanket.' The wealthy tribesmen might flaunt his chief's blanket or bayeta poncho, but the humbler men and women of the nation contented themselves with a coarser blanket of similar size and general proportions.... Burdens of every description, from firewood to babies, were carried in its folds.... It was a garment by day, a blanket by night, an inseparable companion in all seasons.... Its form and proportion survive still in the longish-rectangular rugs, five by eight feet or thereabouts in size, which are among the characteristic products of the modern Navaho loom."

BOSQUE REDONDO AND RESERVATION ERA In 1863 Christopher Carson conquered the Navaho, who were then transferred to Bosque Redondo. The women did very little weaving in captivity and suffered intensely from idleness and inertia. When the Navaho returned in 1868 to their old home, which was now a reservation controlled by the U. S. Government, captivity had reduced them to a "poor white" standard of living, especially in food and clothes. The Government had given them cotton clothing, which gradually came to replace entirely their woolen and buckskin garments. (They had earlier given up wearing their own shoulder blankets because of the weight; a Pendleton blanket was lighter, and when it got wet, it dried quickly.) The flocks upon which the tribe depended for wool had died or been killed. The two sheep per capita granted by the Government to replace the slaughtered stock were insufficient to furnish enough wool for practical purposes. The old market for Navaho blankets had been lost during the absence of the tribe; no longer was there any need to weave them. The tribe was in a sad state.

THE REVIVAL PERIOD After the return of the Navaho, the Government licensed traders to live on the reservation and barter with the Indians. In this way there was initiated a new era in weaving. Traders Hubbell and Cotton were among the first to see the economic value of blankets in their business. The Navaho had little goods to exchange, and if the making and selling of blankets could be stimulated, the traders would profit both by the sale of these products outside the reservation, and by the sale of goods to the Navaho. To this day the relation between trader and weaver has remained extremely close. Youngblood (1937:18,042) reports in his study, "Navaho Trading": "Most traders advance provisions, wool, and dyes to the women for the weaving of rugs. The rug income is of greater economic significance to the Navahos than the values involved would indicate. It is practically the only income they can normally depend upon between wool and lamb marketing seasons." The weaver sells her rugs by the pound. About the year 1880, traders paid her 25 cents a pound; now the prices vary from 65 cents to $1.50 a pound. Thus a large blanket with shoddy weaving, poor dyes, and inartistic designs is expensive simply because of its weight. However, experienced traders recognize quality of work and pattern. They encourage the good weavers by paying extra for their creative ability and by using their blankets as an example to other workers. Conscientious traders refuse to accept poor blankets in order to discourage careless work which reacts unfavorably upon both themselves and the weavers.

In 1890 the tribe sold $25,000 worth of rugs; in 1931 the sum ran into a million dollars (Amsden, p.182). Besides the blankets sold, additional ones are made for home use. The Shiprock Trading Company conducted an experiment to see how much it costs to produce a rug. An experienced weaver came to the store and wove at the rate of 20 cents an hour, producing a 2-1/2 x 5 feet rug of simple pattern which cost the company $40.80, but which in the market was worth only $12. The experiment enabled the company to estimate that a weaver customarily wove rugs at a wage of 5 cents an hour (Amsden, p.236).

The effort of Hubbell and Cotton to stimulate the sale of Navaho blankets was very successful. Other traders followed their example, but the lure of easy profits led many, after 1880, to sell aniline dyes, commercial yarns, like Germantown, and cotton warp to the weavers in order to simplify the work of blanket making and to promote sales. Indeed, they even stipulated the patterns. This resulted in standardization which was alien to the natural versatility and imagination of the weaver. Business boomed until 1900, when the traders and the Navaho weavers discovered that they had defeated their own ends in trying to secure a wide market quickly by lowering the standards of raw materials and the workmanship of an article expensive and tedious to produce. Men like Moore, Hubbell, and Fred Harvey realized what was happening, and they urged the weavers to return to their old standards of work, designs, and colors, and the more careful cleaning and spinning of the wool. They also fought the imitation of Navaho rugs by factories.

To summarize, the revival, dating from 1920, represents a marked effort by associations and traders to encourage the weavers to make again the truly Navaho, geometric designs of strong simplicity in native wool, colored with soft dyes from native plants. They want more Navaho in the rugs and wish "to modify present-day Navaho weaving along old-time lines" (Amsden, p.223).

BLANKET STYLES The traders purchased three major types of blankets: heavy, coarse blankets sold to the American housewife as rugs; saddle blankets; and shoulder blankets which were related to the poncho serape of earlier days. Of the blankets which had become rugs, Amsden writes (p 223): "The Navaho rug came into being because the American demanded a textile meeting his needs and satisfying his graphic concepts; that it retained something (of) the tribal flavor is not due to him but to the weaver, who either could not or would not divest herself completely of her racial individuality."

Bayeta had vanished from the scene by 1975. The garish colors of the later day Germantown yarn and the native wool, both dyed with aniline dyes, replaced bayeta. "As the terraced style was characteristic expression of bayeta, so is the diamond of Germantown" (Amsden, p.213). This pattern was in high favor until 1900, but about 1890 the bordered style had begun to compete with it for popularity. The double-faced blanket, an unusual innovation of this era, never became common.

WEAVING TRADITIONS This post-Redondo period of weaving, which extends into the present, violated almost every tradition and standard of the Navaho weaver. The traditional design, as Amsden (p.216) points out, has a regular, continuous, and horizontal flow, as if cut from a bolt of cloth; whereas the bordered pattern with a central design and emphasis on vertical figures is alien to Indian craft, though a favorite of the white man. Formerly the Navaho had a religious aversion to bordered patterns because of the weaver's fear of "weaving herself into the blanket" and causing illness. A contrasting line or color which breaks the pattern was left as the road out for the harassed soul. This broken line is also to be seen in pottery and ceremonial baskets which have a zigzag design encircling the upper edge.

The women avoid overdoing in weaving. Formerly girls, it is said, were not permitted to weave before their marriage, thereby forestalling any temptation to work too intently. To overcome the effects of immoderate weaving, the woman sacrificed to her spindle a prayer stick of yucca, precious stones, feathers, tassels of grass, and pollen (Ethnologic Dictionary, p.222).

SYMBOLISM In this century experimenting weavers have been making Yei-bitcai blankets which reproduce designs of the sacred sandpaintings and figures of the gods. The Navaho at first objected to the production of these blankets. They have had a good sale, however, so other weavers are suppressing their religious scruples and making the Yei-bitcai designs. The Navaho have never woven special blankets for ceremonial use. Amsden states (p.218): "The Navaho blanket...never has had a ceremonial or sacred function: the sandpainting, the 'marriage basket,' the dance mask, yes--but not the blanket." Reichard (1936:183) presents a similar view: "The Navajo have kept the symbolic designs of their religion apart, in a separate compartment of their minds, from their ordinary blanket and silverwork patterns. The form occasionally overlaps; the emotions are kept distinct."

MAKING THE RUG The Navaho differ from the Pueblo tribes in that Navaho women, and not men, do the weaving. The only exceptions are the nadle, men who are psychically or physiologically peculiar. They have a definite and respected place in the culture and are leaders in artistic work. Navaho legends, in fact; credit them with originating agriculture, basketry, and other crafts.

Practically the entire sheep and weaving industries are controlled by the women. Their husbands and male relatives assist in some of the care of the sheep, but this does not affect ownership. The women own the sheep; select the wool they want for weaving; sell the excess wool and meat; spin the yarn; weave the rugs, and sell them.

Reichard's book, "Spider Woman," entertainingly presents her personal experience in learning to weave among the Navaho on the reservation. Her later publication, "Navaho Shepherd and Weaver," gives detailed information on dyes, the selection of wool for weaving, every process in making a blanket, and how different types of weaves are produced. Amsden's book, "Navaho Weaving," deals more with the history and development of weaving, while Reichard has specialized in weaving techniques and the psychology of the weaver. Amsden relates the history of looms throughout the world, gives basic information on the art, and in addition has numerous photographs, many of which are in color, illustrating scenes from Navaho life, blankets, equipment, and processes of weaving.

PROCESSES The main processes in making a blanket are: selecting the wool, carding, spinning, washing, dyeing, and weaving. The care and the semiannual shearing of the sheep were described under Livestock. The scrawny, native sheep of the Navaho produce a wool particularly suitable for the weaver's purposes, as it is coarse, straight, greaseless, and with a long staple which does not gather dirt and briers as quickly as fine, curly, short wool. Wool for weaving is selected from the back of the sheep, where it is thicker and cleaner than on the belly.

CARDING It is needless to remark on the scarcity of water among the Navaho and why formerly the weaver did not wash her wool or yarn at all. She picks out as much dirt from the wool as she can, and then cards it to clean out more dirt and to lay the fibers evenly and ready for spinning. The first cards were Spanish and consisted merely of teazels--long-spined thistles--clamped into a wooden frame. Now cards with slender, iron spikes, fastened in a wooden frame, are used.

SPINNING Next, a bit of the "curl," into which the carded wool has been evenly fluffed, is fastened to the tip of the spindle with a wet finger and then gently drawn out into a strand. The spindle is a simple instrument--a slender stick with a round disc at its base. (A European weaver uses a spinning wheel to accomplish what the Navaho does with the spindle.) Although the Navaho saw the Spanish use the spinning wheel, they have never shown any inclination to adopt it, perhaps because of its incompatibility with their semi-nomadic existence.

The yarn must be spun several times. Weft is usually spun twice, while warp, the stationary element, is spun as many as five times to make it strong and enduring, so one can understand why the cotton warp sold by the traders was welcome. The weavers still buy it, but some also get warp of native wool from women who specialize in making it.

WASHING AND DYEING Weavers differ among themselves as to when the weft should be washed--if this is to be done. In the earliest times the yarn was not washed at all; later yucca suds were used. Now when water is easier to obtain, because of windmills and artesian walls, the yarn is more likely to be washed. For dyeing, the well-known commercial packaged dyes may be employed, or an ardent craftswoman may go to the trouble of preparing colors from native plants. Those native dyes are far softer and richer in color than the commercial products now being manufactured for the Navaho trade in colors to imitate the old vegetable dyes. The weaver does not dye her warp; in a good blanket it should not show, because the weft is beaten down so closely that it is hidden.

WEAVING The loom is a native American device of the kind used by the ancient cliff dwellers, and it has not changed through the centuries, nor have the spindle and the other weaving implements used with the loom. Generally the men construct the loom which is either inside a hogan or under two trees which may form the side posts, or under a leafy, summer shade. (See Plate II, p.15.)

A simple description of the loom fellows. The men first erect a rectangular frame of four poles, and a yard beam is slung with a rope to the upper cross pole. The yard beam releases the warp so that it will be within the weaver's reach. Next the men lay out on the ground a frame of the size intended for the finished blanket and the women string it with unbroken warp from top to bottom. Strong cord, used for binding off the completed blanket, is strung along the sides and the top of this frame. Then the men fasten the blanket loom into the frame, and the workers firmly attach it at the bottom so that the warp will be taut. The healds consist of loops of yarn fastened at their upper end to a slender stick which falls across the width of the blanket. The lower ends of the loops are attached to each alternate strand of warp. With the aid of a comb-awl and the healds, the weaver can insert a batten (a long stick) through the alternate threads of the warp. She can then shuttle the weft yarn through. Before removing the batten, she uses it, or the comb, to push down the weft against the finished part of her weaving to make her blanket strong and waterproof.

Weaving is essentially a leisure time activity. Exceptionally artistic weavers may be released from some of the daily chores to devote as much time as possible to their looms. The others weave in winter. In their few spare moments during the busy spring, summer, and fall, they may prefer to do pick-up work like carding, spinning, and dyeing.

The mythical loom built by Spider Man for Spider Woman had cross-poles of sky and earth cords, warp sticks of sun rays, and healds of rock crystal and sheet lightning. A sun halo formed the batten, and white shell the comb. There were four spindles: One was a stick of zigzag lightning with a whorl of cannel coal; the second of flash lightning and turquoise; the third of sheet lightning and an abalone whorl; and the fourth was a rain streamer with a whorl of white shell. (Reichard, 1934.)

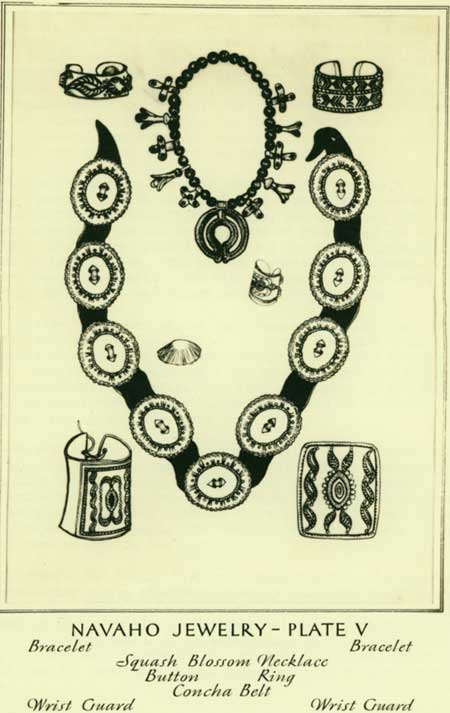

PLATE V. NAVAHO JEWELRY. Bracelets (top left and right). Squash Blossom Necklace (top, center). Button (center left). Ring (center right). Concha Belt (center). Wrist Guards (bottom left and right). |

SILVERSMITHING

HISTORY OF SILVER WORK The Navaho had worn silver jewelry for almost century before there is any evidence that they knew how to make it themselves. In 1795 a Spanish reference (Amsden, 1934:132) comment that the Navaho "captains" were rarely seen without their silver ornaments. After that date mention of the silver necklaces and the leather belts decorated with large silver discs is fairly frequent in the early sources. No one states specifically that the Navaho made their own jewelry. Investigators assume that the Mexicans (the American descendants of the Spanish), who were the leaders in silver work, were the jewelers for the Navaho and the rest of the Southwest.

In 1881 Dr. Washington Matthews ("Navaho Silversmiths," 1883) was told on the reservation that the Navaho had made great progress in silversmithing during the preceding fifteen years and adds that "they attribute this change largely to the ... introduction of fine files and emery paper." The Ethnologic Dictionary (p.271) also gives the middle nineteenth century as the time of introduction. The old silversmiths of the tribe claim that the Mexicans taught the Navaho, and cite the case of a colleague, satsidi ani, or "old smith," who was taught by Cassillo, a Mexican.

C. N. Cotton, a trader, stated that when he came, in 1884, Navaho silversmiths were rare (Hodge, 1928). The tribe depended on itinerant Mexican smiths to make up silver ornaments for the Navaho in exchange for horses. Usually the Navaho had a few of their boys working the bellows for the Mexicans, and before long they had picked up knowledge of the craft. As usual when the Navaho are interested in something, they excelled their teachers in silversmithing.

The earliest smiths were on the eastern side of the reservation, which had more contact with the Mexicans. Later the southern part of the reservation took the lead, which it still maintains because of the wholesale and retail trade along the railways. Smiths are uncommon elsewhere on the reservation, although there is generally one in the region of a major trading post. The southern smiths, however, supply most of the jewelry worn in the north.

CRAFT DEVELOPMENT The Navaho then had apparently begun to experiment with silversmithing during the years directly preceding their removal to Basque Redondo. After their return the development of this craft received fresh impetus, largely, as Matthews points out, because of the introduction of modern tools. It is interesting that in silversmithing, as in weaving, the early period is the greatest. The most artistic work was created when the craftsmen worked principally to satisfy tribal needs and tastes.

At first the smiths used brass and copper wire. Later they cast American silver dollars to obtain the metal and they also used the Mexican peso when it fell in price. Now they get sterling silver ounce bars or sheet silver from the traders. Bodinger, who has written a general account of the history of Navaho silver work, states (p.16): "The United States silver is bluish and takes a harder, higher polish. The Mexican is white and has a more 'silver,' frosted appearance when polished by wear."

The most talented of the few smiths in Matthews' time were making such complex articles as powder chargers; tobacco cases shaped like the army canteens; hollow, round beads; and headstalls for horses. In addition they made the more common types of jewelry--bracelets, rings, buttons, ornaments for horse gear and for the leather guards ("gatos") worn to protect the wrist when shooting a bow. The necklaces of hollow, round silver beads were usually finished with a double crescent-shaped pendant or a double-barred cross and a few conventional silver blossoms known to the trade as "squash blossoms." (See Plate V, p.73.)

Originally the Navaho silversmiths used only the silver without settings. Even after 1900, when they began to use turquoise, garnet, cannel, coal, jet, abalone shell, peridot, end other semi-precious stones valued by the Navaho, they much preferred small settings to enhance the soft sheen of silver. The people of Zuni Pueblo, who, about 1880, learned silver working from the Navaho, are very fond of turquoise settings and use silver principally to hold the pieces of turquoise together, as Bedinger points out. During the recent depression several Zuni women took up silver work; among the Navaho it is still exclusively a man's craft.

Turquoise has been a sacred gem of the Southwest since prehistoric times. The Indians obtained their finest turquoise of a clear blue from the people of Santo Domingo, who mined it at Cerillos near Santa Fe. In early historical times the Navaho traded blankets for the stones. The so-called "Spider Web" turquoise with its black tracery on dark blue comes from Nevada, while a mottled green is mined at Tuba City, Arizona, and a pale blue stone with a robin's egg cast is obtained from secret mines. The finest turquoise is a vivid clear blue. A soft stone absorbs moisture and grease, turns green, and depreciates in value. (Bedinger.)

MODERN WORK Like Navaho rugs, Navaho jewelry is imitated in factories; one even sees "Navaho-style" jewelry in department and ten-cent stories. The present era of silver work is comparable to the boom years of weaving when shoddy materials, poor workmanship, and ornate design were used to bring down the price to a popular level. Navaho craftsman now make objects to order in curio shops or at home, and the employers give them a carefully measured quantity of silver and turquoise, from which the workers are expected to turn out as many articles as possible. The result is that the objects are thin and brittle and sell at a low price. The character and design of the articles also are dictated by trade demands: swastikas, thunderbirds, and arrows predominate in the cluttered patterns on cigarette boxes, ash trays, and ornaments. Artists still make beautiful jewelry, but it is principally for tribal use. It is expensive because of the weight and quality of silver. In this artistic work one still sees the feeling for design and beauty displayed by the jeweler working to please himself. The native design consists of elementary geometrical forms which follow the contour of the article and leave smooth, softly gleaming expanses of silver.

JEWELER'S EQUIPMENT Matthews and the Ethnologic Dictionary describe the crude equipment and tools with which the craftsman in early times turned out beautiful work. The iron tools were obviously acquired directly from white people or indirectly through the Mexicans, because aboriginal Americans did not have iron tools before the Europeans came. The essential equipment consisted of an adobe and stone forge; charcoal from juniper; bellows of sheep or goat skin; a pottery dish for a crucible; moulds cut from sandstone, wood or iron in the shape of the article to be made; scissors for cutting plates of metal and for tongs; hammers to beat out silver in wrought work; an anvil of any piece of hard stone or iron; iron pliers, files, knives, and awls for engraving and chasing; a blowpipe of brass, which was only a wire beaten into a flat strip and bent into a tube, for soldering pieces together with the aid of saliva, borax, or silver dust; rags soaked in tallow for a soldering flame; almogen and rock salt for blanching tarnished silver; powdered sandstone, ashes, and sandpaper for polishing the completed article.

The silver right be either smelted or wrought, or both processes would be combined in producing such a complicated article as a powder charger. In making conchas (Spanish for "shell"), which are large, round, silver discs strung on a leather belt, from three dollars to four dollars worth of silver is needed to make a single ornament. A leather belt with ten conchas will, therefore, contain as much as $40 worth of silver. (See Plate V, p.73)

POTTERY

The Navaho women have never made much pottery or basketry. Even as early as 1855 it was so scarce that Letherman reported that they had no pottery at all: they exchanged their blankets for Pueblo pots and Shoshonean baskets. Now they rarely make any baskets and earthen-ware except those required in religious ceremonies, for tin pans, kettles, and buckets from American traders serve everyday needs. The tradition in the Origin Legend, that long ago artistically decorated and fine pottery was made, has no archaeological evidence to support it (Wetherill).

The pottery is of crude, coiled type, which Kidder notes is more like the potsherds off western Nebraska sites than Pueblo designs. It may be, then, that the Navaho had learned to make pottery before they entered the Southwest. In early historic times they made ordinary cooking pots, bowls, dip spoons, and conical pipes through which smoke was blown to produce cloud-like effects during religious chants. The cooking pot is very frequently used ceremonially as a drum, after a hide has been stretched across the mouth. Earthen crucibles for silver work are an innovation of later times. The Ethnologic Dictionary (pp. 285-291) has descriptions and sketches of technique and types.

BASKETRY

Navaho basketry is closely woven and durable, although limited in type. Until recently the tribe made water bottles of coiled basketry, globular in shape, narrow-necked with a wide rim and waterproofed with pine or pinyon gum. At one time they also made baskets for gathering seeds and fruits, but Mr. Ben Wetherill states that he has never seen these in use during his thirty-five years residence in the area. These baskets were slung over a shoulder, or carried by means of a tump line, which fastened about the forehead. See the Ethnologic Dictionary (pp. 291-300) for a detailed description of basket making and types.

One of the most characteristic types is the "wedding basket," so called by traders because bride and groom eat from such a basket in the native wedding ceremony. It is used, however, in any ceremony which requires a receptacle. Thus, a chanter might keep his religious paraphernalia in it; or use it to hold yucca suds for ceremonial bathing; or, by inverting it, he can even use it as a drum. This sacred basket is shallow, being about three inches deep end twelve to fourteen inches across, and has a zigzag pattern in red and black around the rim. Matthews (1894) describes the rituals involved in the manufacture and use of this basket. The Navaho also obtained it by trade from the Paiutes, who observed the ritual rules for its manufacture as specified by Navaho tradition.

Aside from its importance in religion, the wedding basket is of interest to anthropologists because its type and design elements are similar to the ware of the early Basket Makers, who lived in the Southwest about a thousand years before the Navaho. The older "sacred basket," designated generally as "Old Navaho," was made with a foundation of two rods and a bundle similar to that of the Basket Makers. Formerly this kind of foundation was widely used in the Southwest by the Shoshoneans, Pueblos, and Apache, as well as by the Navaho. The Navaho may have learned it from the Paiute. It was replaced by the three-rod and other types of foundation among most of these tribes. The Paiutes now employ the three-rod foundation in making the Navaho trade baskets, but use a different technique in making ware for their own use. (Wetherill information; Weltfish, 1930, 1932) The continuity of design elements can be seen in Amsden, Pl. 4; Guernsey & Kidder, 1921: Pl. 28; and F. H. Douglas.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2006 10:00:00 am PDT |