|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 1 A Preliminary Survey of Fauna Relations in National Parks |

|

APPROACH TO WILD-LIFE ADMINISTRATION

The national parks of the United States began by rescuing from the immediate dangers of private exploitation certain areas which were climax examples of Nature's scenic achievements.

With rapid expansion of frontiers to the end that European culture not only replaced that of the red man but actually altered the physical appearance of his environment, the national parks were quickly projected into a larger sphere of purpose. This involved a magnificent conception. The American people intrusted the National Park Service with the preservation of characteristic portions of our country as it was seen by Boone and La Salle, by Coronado, and by Lewis and Clark. This was primitive America, and it was to be kept for the observation of the recreation-seeking public and scientists of to-day, and their descendants in the generations of to-morrow.

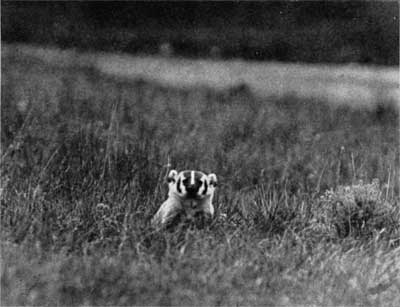

FIGURE 1 – American badger, one of the fur-bearers that is losing its fear of man in the national parks. Photograph taken June 25, 1930, near Lamar River, Yellowstone. Wild Life Survey No. 699 |

PLACE OF WILD LIFE IN AMERICA'S CIVILIZATION

Throughout the new land, the wild-life resources were a vital necessity to the explorer. He penetrated the wilderness for fur. This was the first great crop to be harvested. Wherever he went, he depended upon the game for his very existence. So it was in evitable that the history and tradition of our national life should be replete with references to the animals that occurred so profusely. Emblematically, we live among these birds and animals to-day. Witness the eagle and the buffalo of our coins, the antlered emblems of fraternal orders, the wild creatures depicted on State flags and seals. Daily speech bristles with descriptive words based on concepts of these animals and their habits.

Yet many species continue to exist in the living state only as small remnants hidden away in the wildest corners of the country, remote from the perils of human contact. Others have persisted through their ability to escape greedy human eyes. With the alteration of their habits to meet the rigors of civilization, many of them are no longer to be observed in their primitive state.

To all of this the national parks present one of the outstanding exceptions. In them, the carnivores classed as predatory find their only sure haven. Fur-bearers and game have benefit of partial protection elsewhere, but in the parks alone are they given opportunity to forget that man is the implacable enemy of their kind, so that they lose their fear and submit to close scrutiny.

The national parks owe much of their unique charm to the unusual opportunities they afford for observing animals amid the intimacies of wild settings in which even the observers feel themselves a part. It is one of the causes contributing to their constantly increasing popularity. The thrill of being in the same meadow with an elk, no fence or bar between, reaches everyone, young or old. Without the scurry and scratch of a chipmunk along the bark or the call of a jay and the flash of its blue, the high mountain and the deep gorge would be cold, dead indeed. The visitor would not linger long after his first comprehensive gaze at awesome scenery if the vista did not include the intimate details of those living things, the plants, the animals that live on them, and the animals that live on those animals.

Appreciation of the importance that the wild life commands among the resources of the national parks rests upon comprehension of the important points developed above.

In logical sequence, these points are:

- That the wild life of America exists in the consciousness of the people as a vital part of their national heritage.

- That in its appointed task of preserving characteristic examples of primitive America, the National Park Service faces an especially important responsibility for the conservation of wild life. This is emphasized by the wholesale destruction which has decimated the fauna in nearly every part of the land outside of the park areas.

- That the observation of animals in the wild state contributes so much to the enjoyment derived by visitors that this is becoming a park attraction of steadily increasing rank.

FIGURE 2 – Long-crested jay looks out over the Grand Canyon rim. "Without . . . the call of a jay and the flash of its blue, the high mountain and the deep gorge would be cold, dead indeed." Photograph taken October 30, 1930, at El Tovar, Grand Canyon. Wild Life Survey No. 1904 |

CONSERVATION OF THE WILD-LIFE RESOURCES OF THE PARKS

Recognition of these factors by those entrusted with the care of the parks led to intensification of the protective function until vandalism was wiped out, while poaching has been reduced to a minimum in all but a few parks where it, too, will be eliminated as conditions grow more favorable. But this part of conservation has not been enough. The need to supplement protection with more constructive wild-life management has become manifest with a steady increase of problems both as to number and intensity.

An early example of classic note is the bison of Yellowstone. The necessity of saving the bison left no alternative to intensive management. No one questioned the sacrifice of policy involved in the maintenance of the herd in a state that was only semiwild. It was either that or lose the great buffalo to this country except as Exhibit A in a zoological garden.1 Still, this case was an exception, and no one even for a moment considered that it established a precedent for dealing with other species.

FIGURE 3 – American bison frequent a lake-bottom wallow. Management was necessary to preserve this member of the park fauna. Photograph taken September 17, 1929, Lamar Valley, Yellowstone wild Life Survey No. 415 |

The policy of noninterference with wild life became more and more deeply intrenched. Protection would do the rest. Nevertheless, time proved that management of some sort would have to be invoked to save certain situations, especially as the parks were opened to thousands of visitors, causing a flood of fresh complications.

The conclusion was unavoidable. Protection, far from being the magic touch which healed all wounds, was unconsciously just the first step on a long road winding through years of endeavor toward a goal too far to reach, yet always shining ahead as a magnificent ideal. This objective is to restore and perpetuate the fauna in its pristine state by combating the harmful effects of human influence.

The park faunas face immediate danger of losing their original character and composition unless the tide can be turned. The vital significance of wild life to the whole national-park idea emphasizes the necessity for prompt action. The logical course is a program of complete investigation, to be followed by appropriate administrative action.

The unique feature of the case is that perpetuation of natural conditions will have to be forever reconciled with the presence of large numbers of people on the scene, a seeming anomaly. A situation of parallel circumstance has never existed before. Therefore, the solution can not be sought in precedent. It will challenge the conscientious and patient determination of biological engineers.2 And because of the nature of the task, it is inherently an inside job. Constancy to the objective can be made a certainty only by employment of a staff whose members are of the Service, conversant with its policies, and imbued with a devotion to its ideals.

1 The Extermination of the American Bison, with a Sketch of its Discovery and Life History, by Hornaday, William T. Report of United States National Museum, 1887, pp. 369-548.

2 A designation applied by, Dr. Alexander Ruthven and others to workers in this field.

HISTORY AND PROGRAM OF THE SURVEY

During service with the educational department in Yosemite National Park in 1928 and 1929, thoughts of this trend led one of the writers to the hope that something might he done towards concentrating greater interest on the fundamental aspects of wild-life administration throughout the national-park system. In collaboration with another of the co-authors, the general outline for a preliminary investigation was developed. Having received the sanction of the director, the idea then assumed concrete form under his guidance, becoming at once the Preliminary Wild Life Survey, with headquarters at Berkeley, California.

Personnel included Joseph S. Dixon, economic mammalogist; George M. Wright, scientific aide in the National Park Service; Ben H. Thompson, research associate; and Mrs. George Pease, secretary. All expense of the survey, inclusive of office, field, and salaries. was met with private funds until July 1, 1931. Since then it has been supported about equally from public appropriation and private contribution.

Stated objectives were:

- To focus attention upon the need for a well-defined wild-life policy of the National Park Service, including the extension of the protective function to embody a definitely constructive program.

- To assist park superintendents in dealing with the urgent animal problem immediately confronting them.

- To present a report which would delineate the existing status of wild life in the parks, analyze unsatisfactory conditions, and outline a proposed plan for the orderly development of wild-life management.

The present paper is intended to fulfill the third objective. In the meantime certain results. have been attained toward the accomplishment of the first and second purposes and may be mentioned briefly here.

Through the existence of a group actively functioning in the field, the director was provided with arguments and data and with a living organization for which he could solicit support to assure perpetuation. This has facilitated the securing of one permanent position of field naturalist and appropriations to cover the field expenses of the staff. Office quarters were provided in conjunction with field offices of the Branch of Research and Education of the National Park Service in Hilgard Hall, University of California, Berkeley, Calif. Thus the foundations of a wild-life organization as a continuing function of the Service have already been laid.

The photographic collection, numbering 2,523 negatives and accompanied by prints all filed and indexed in readily available form, is proving useful to the educational program. Though its prime purpose is for scientific record, the service rendered in this other field increases its value measurably.

Field notes on 279 species of birds and mammals have been systematically recorded. In part they have provided data for the report, but the whole of them remains an important reservoir of classified information for the intensive biological studies which should follow the first general investigation.

Nevertheless, throughout the preliminary survey, fixity to the main purpose of obtaining a perspective of the problem in its entirety has been the paramount consideration. Consequently, the search focused on the general trends in the status of animal life, with particular regard to the motivating factors. If a finger can be placed on the mainsprings of disorder, there is hope of discovering solutions that will be adequate in result. Meeting existing difficulties with superficial cures might be temporarily expedient and, in cases of emergency, necessary, but if continued would build up a costly patchwork that must eventually give out. It would be analogous to placing a catch-basin under a gradually growing leak in a trough and then trying to keep the trough replenished by pouring the water back in. The task mounts constantly and failure is the inevitable outcome. The only hope rests in restoration of the original vessel to wholeness. And so it is with the wild life of the parks. Unless the sources of disruption can be traced and eradicated, the wild life will ebb away to the level occupied by the fauna of the country at large. Admitting the magnitude of the task, it still seems worth the undertaking, for failure here means failure to maintain a characteristic of the national parks that must continue to exist if they are to preserve their distinguishing attribute. Such failure would be a blow injuring the very heart of the national-park system.

The field studies were conducted in accordance with this point of view. Findings as presented in this report are calculated to lay a foundation of approach and practice useful in dealing with wild-life problems of all categories wherever or whenever they may occur, rather than to stand as an enumeration of a lengthy list of individual problems without correlation. However, numerous examples have been given detailed treatment in the development of the arguments, and in a separate section all problems. met with in each area have been enumerated in order to record for future reference situations obtaining in the parks at the time of the investigation, as seen by the field party.

In the following pages the technique developed for the preliminary survey is detailed for the benefit of others who may undertake similar projects and for the usefulness it will have as a skeletal outline for the intensive studies in each park later on. Further, this account of the methods employed will facilitate a critical evaluation of the results.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/1/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016