|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 2 Wildlife Management in the National Parks |

|

PART II

PRESENT STATUS OF NATIONAL PARKS WILDLIFE AND THE RESTORATION PROGRAM

REPORTS CONCERNING ADMINISTRATIVE

PHASES OF WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

The reports and data compiled in this brief section pertain to wildlife restoration ultimately, but more immediately to restoration through certain administrative arrangements.

The letter to Mr. Thomas C. Vint, Chief of the Branch of Plans and Design, National Park Service, indicates how closely wildlife management integrates with and transects the construction phase of national-park development, and incidentally, all other phases of national-park administrative activities.

The reports on buffer areas and research areas are an attempt to arrive at a comprehensive, long-time plan for developing national parks so that developments shall exert a minimum of malinfluence on the wilderness characteristics of the parks and outside influences shall be buffed down into compatible proportions. Buffer areas, in other words, would act as transformers to step-down the high, disruptive pressure against native forms coming from outside the parks. The research areas report is an attempt, specifically, to zone the parks, from the administrative point of view, toward securing the maximum preservation and utility of their wilderness sections for scientific purposes directly, and indirectly for the ultimate benefit of everybody.

The reports are, otherwise, self-explanatory.

REPORT CONCERNING OVERGRAZING AS A

LANDSCAPE PROBLEM

Submitted to the Chief of the Branch of Plans and Design, National Park Service, May 28, 1934

Copy of Mr. Frank E. Mattson's memorandum to you, relative to overgrazing in northern Yellowstone as a landscape problem, has been received and read with much interest. I think that Mr. Mattson has described the situation just as it is and has drawn the only conclusion that can be drawn from such a circumstance, namely, that this overgrazed condition is not only a wildlife problem but a landscape and forestry problem as well.

EFFECT OF WILDLIFE UPON THE LANDSCAPE

There are several cases where overgrazing has seriously changed the landscape. A few pictures, depicting representative cases, are included here because they are much easier to take than long written descriptions of the cases would be.

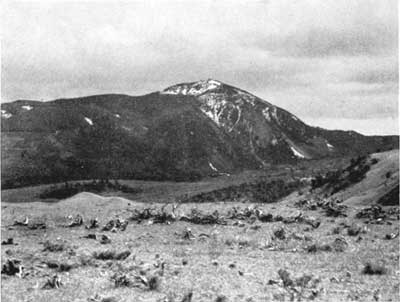

Figure 46. – Elk trails scarring the hillsides, about which Mattson spoke. (Photograph taken May 19, 1932, at Mammoth Hot Springs, Yellowstone. Wildlife Division No. 2258.) |

Figure 47. – Elk-browsed junipers and Douglas firs along the road between Mammoth and Gardiner. This is not only a landscape problem of today, but of the future, for practically no coniferous reproduction is succeeding. (Photograph taken June 8, 1932, near Mammoth Hot Springs, Yellowsone. Wildlife Division No. 2542.) |

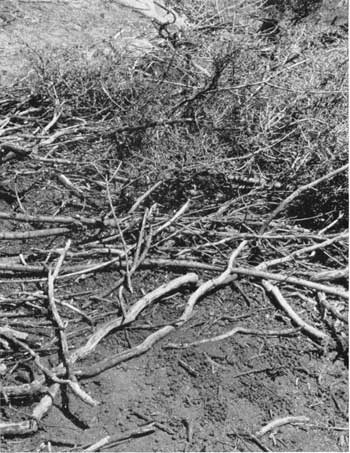

Figure 48. – Carcasses, but not of elk; just sagebrush remains of the once luxuriantly sage-covered hills of northern Yellowstone. (Photograph taken May 23, 1932, Mount Everts, Yellowsone. Wildlife Division No. 2037.) |

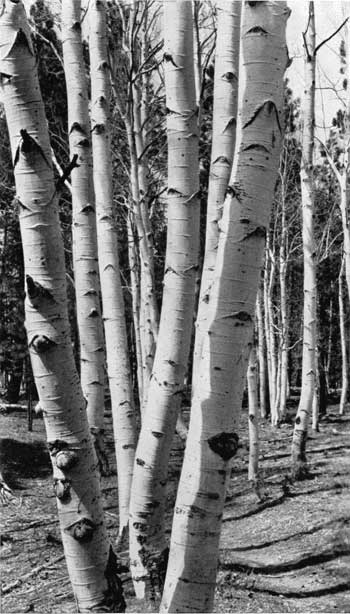

Figure 49. – Aspen trunks, smooth and white, as they normally grow. (Photograph taken May 29, 1933, Bright Angel Point, Grand Canyon. Wildlife Division No. 3685.) |

Figure 50. – Aspen trunks, scarred and black after elk have stripped them of their bark. (Photograph taken July 29, 1931, Geode Creek, Yellowsone. Wildlife Division No. 2012.) |

Figure 51. – The final result : Old trees dying, reproduction a mass of dead sticks, and the aspen grove falling to pieces. This is characteristic of Yellowstone's and Rocky Mountain's overcrowded elk winter range. (Photograph taken September 17, 1933, on Tower Falls Road, Yellowsone. Wildlife Division No. 3281.) |

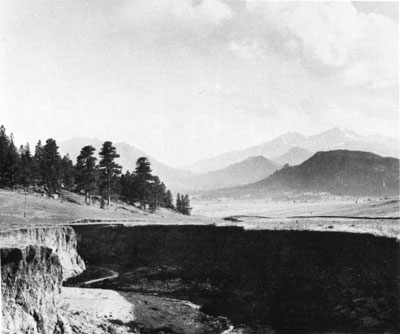

Figure 52. – Erosion symphony — the beautiful meadows of Estes Park, gutted out to the tune of thousands of tons of fertile soil annually. This particular gully is probably the result of overgrazing plus a misplaced road which at one time meandered up the natural drainage course of the meadlow. But the scene is also characteristic of a number of parks and monuments in the Southwest. (Photograph taken June 23, 1931, Estes Park, Rocky Mountain. Wildlife Division No. 1991.) |

Figures 53 & 54. – Scenes along East Rim Drive in Grand Canyon — all that is left of dense growth of Gamble Oak and Cowania. Cattle grazing within the park is the explanation. (Photographs taken June, 4, 1933, near Grand View, Grand Canyon. Wildlife Division Nos. 3299 and 3294.) |

Figure 55. – The deer-browsed manzanitas of Yosemite Valley. (Photograph taken March 29, 1930, Yosemite Valley. Wildlife Division No. 567.) |

Figure 56. – Strange little ponderosa pine as seen along roadsides in Rocky Mountain, Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and Sequoia. Cause: Elk and deer browsing. (Photograph taken March 30, 1930, Yosemite Valley. Wildlife Division No. 566.) |

Figure 55. – The deer-browsed manzanitas of Yosemite Valley. (Photograph taken March 29, 1930, Yosemite Valley. Wildlife Division No. 567.) |

Figure 56. – Strange little ponderosa pine as seen along roadsides in Rocky Mountain, Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and Sequoia. Cause: Elk and deer browsing. (Photograph taken March 30, 1930, Yosemite Valley. Wildlife Division No. 566.) |

Figure 57. – The once lush growth within and about Giant Forest, Sequoia National Park. The cause is evident. (Photograph taken April 28, 1933, Giant Forest, Sequoia. Wildlife Division No. 2989.) |

Figure 58. – The once lush growth within and about Giant Forest, Sequoia National Park. The cause is evident. (Photograph taken June 10, 1933, Round Meadow, Sequoia. Wildlife Division No. 3118.) |

EFFECT OF LANDSCAPING DEVELOPMENTS UPON THE WILDLIFE

Another angle of the situation is just about the reverse of that shown in the pictures. That is, the pictures show where wildlife has damaged the landscape; the reverse order is where developments are detrimental to the wildlife. This is too long to go into, but the mere mention of a few cases is sufficient, namely, mosquito and swamp control around centers of habitation; roads and waterfowl nesting sites (see fig. 59); roads and wilderness areas; roads and mountain sheep range, as in the case of the Trail Ridge in Rocky Mountain; water utilization and fishing, as in the Never Summer Range in Rocky Mountain (see fig. 60); camp grounds, parking areas, industrial centers, and such, which take portions of winter range and are inimical to the presence of large game animals. Merely to mention these is to indicate how minutely the wildlife and landscape values dovetail.

Figure 59. – High-Line Canal along the Never Summer Range in Rocky Mountain — a beautiful landscape scar and a fine robber of fishing streams, beaver ponds, and game range below. (Photograph taken June 27, 1931, Never Summer Mountains, Rocky Mountain. Wildlife Division No. 2303.) |

Because of the same problem having at least these two aspects, each of which is handled by a separate branch of the Service, it is proposed that it would be advantageous if the Branch of Plans and Design should send to the Wildlife Division copies of reports and correspondence relative to overgrazing, erosion, and other cases where your men have noticed that animal life is destroying landscape values, and that there be a reverse exchange of data where situations warrant it. In this way it is felt that many problems which are tackled separately might find quicker and more satisfactory solution.

Figure 60. – The reverse of the story — waterfowl nesting site makes way for road in Zion. (Photograph taken May 27, 1931, Zion Canyon. Wildlife Division No. 1833.) |

REPORT CONCERNING RESEARCH RESERVES IN

NATIONAL PARKS

Submitted to the Director of the National Parks Service, February 23, 1934

Following receipt of your letter of June 6, 1933, making the Wildlife Division responsible for promotion of the research-reserves program in the national parks, I called a conference of our group for the purpose of developing a plan of action.

After careful study and deliberation we have concluded that some changes in the original research-reserve plan would have to be made to secure conformity with basic parks policies and to facilitate a locking into the administrative code. Unless this be done, the research-reserve plan could never get beyond the paper stage.

We believe that we have arrived at a plan which will satisfy the need.

RESEARCH RESERVES

To our knowledge, areas have been designated as research reserves in Grand Canyon, Lassen Volcanic, Sequoia, Yellowstone, and Yosemite National Parks. A formal survey in the form of an original inventory of biotic communities of the Yosemite Research Reserve has been started. Another area has been recommended as a research reserve in Rocky Mountain National Park. * * *

It is our opinion that, with the exception of the Yosemite Research Reserve, which is being studied by the Yosemite Field School, universities or other suitably equipped institutions should be induced to undertake the formal studies of research reserves within the national parks.

All available correspondence relative to research reserves has been carefully studied and discussed. Dr. Shelford's memorandum1 on nature sanctuaries has been the basis for evolving a nomenclature and definition of terms in considering research reserves within the national parks.

Shelford's definitions of classes of nature sanctuaries are as follows:

1. First-class nature sanctuaries:

Any area of original vegetation, containing all the animal species historically known to have occurred in the area (except primitive man) and thought to be present in sufficient numbers to maintain themselves, is suitable for a first-class nature sanctuary.

2. Second-class nature sanctuaries:

A. Second-growth areas (of timber) approaching maturity, but conforming to the requirement of no. l in all other respects.

B. Areas of original vegetation from which not more than two important species of animal are missing.

3. Third-class nature sanctuaries:

Areas modified more than those described under no. 2.

This excellent classification is something toward which to work. There are several difficulties to be overcome, however, before research reserves within the national parks and monuments can attain the first-class nature sanctuary status which they should. It seems important to outline briefly these difficulties in order that a program of progressive restoration may be undertaken toward the setting up and maintenance of research reserves.

I. No first- or second-class nature sanctuaries are now to be found in any of our national parks under their present condition. The reasons are:

(a) No park is large enough in its entirety to provide protection and habitat unmodified by civilization for the large ungulates and carnivores. To be specific, Yellowstone, the largest national park, cannot provide winter range for its buffalo, elk, deer, antelope, and mountain sheep. If a few wolves occasionally wander into the park during summer, as recently has been reported, they go to lower country in winter, which is outside the park. Moreover, it is probable that white-tailed deer, cougar, lynx, wolf, and possibly wolverine and fisher are gone from the Yellowstone fauna. Add the grizzly to this list, and you have the carnivore situation at Rocky Mountain. In Grand Canyon, feral burros have decimated every available bit of range within the canyon, and domestic stock have taken heavy toll from the narrow strip of South Rim Range. Cougars have been almost extirpated, and bighorn greatly reduced. The entire ground cover and food supply for ground-dwelling birds and small mammals has been changed by grazing. In Yosemite the bighorn and grizzly are gone and cougar almost gone. In Glacier the grizzly is scarce, the buffalo and trumpeter swan are gone, and game in general is seriously depleted because of inadequate boundaries. There is no need to repeat the story for the smaller parks. By definition, then, none of the larger parks can provide a first- or second-class nature sanctuary at present.

(b) The irregularity and arbitrary character of boundaries of existing national parks provides insufficient buffer areas to protect the research reserves, even if first-class nature sanctuaries were available as research reserves. A research reserve must be located somewhere near the center of a large national park, or else be protected by some adequate faunal barrier, in order to provide sufficient and adequate buffer area around it. Otherwise, the large carnivores and the fur bearers which are killed and trapped around the nearby boundary of the park will be drained from the normal fauna of the research reserve. This is exactly what has happened to the entirety of each of our large national parks. The results have just been listed above under (a).

This matter of external influence incessantly acting upon the faunal resources of a national park cannot be overestimated. The fate of the carnivores and fur bearers is too well known. The ungulates are robbed of their winter range and held within the park during winter, by virtue of hunting and civilization just outside the boundaries. This means artificial feeding of big game, congestion at feeding stations, and spread of disease, abnormal concentration of predators, and overgrazed range with all its succession of maladjustments, not the least of which is the loss of food and cover for ground-breeding and ground-dwelling birds and small mammals. Add to this the depletion of rare wild fowl outside the park, such as trumpeter swan, sandhill crane, some ducks and geese, etc., and it becomes evident that the attempt to handle the salvation of wildlife from within a sanctuary is a futile attack. The success of the sanctuary depends largely upon what is done outside the sanctuary to make it a real and adequate haven for wildlife.

(c) Let us hook at some of the research reserves which have already been designated to see how the above-mentioned factors operate. There are four research reserves in Lassen Volcanic National Park. Lassen is approximately 10 by 16 miles square, enclosing the volcanic cone. The description of the research reserves is as follows:

Research Reserve No. 1. — "Approximately 2 1/2 square miles at north boundary of park * * *."

Research Reserve No. 2. — " Approximately 1 1/2 square miles in Lost Creek drainage at north park boundary * * *."

Research Reserve No. 3. — "Strip 3/4 mile wide and approximately 5 miles long * * * ending at south boundary."

Research Reserve No. 4. — "Two plots totaling approximately 4 square miles in Hat Creek Valley. Area to be reserved in devastated region for study of succession. Area entirely denuded by 1915 eruptions, leaving loose rocky volcanic ash and rock covering."

No. 4 is valuable for floral succession study. But in the light of the above listed factors which work against the fauna of a national park at all times, of what value are nos. 1 to 3?

These samples, to be sure, are in a small national park. Are there none better in the larger parks? Grand Canyon seems promising. Here there are five research reserves. Three of these are such isolated temples rising out of the canyon that they cannot be developed for commercial or human utilization and therefore appear to be protected. The other two are on the North and South Rims and are so close to the boundaries of the park that their biotic character will always be affected by activities just outside the park.

Yellowstone might present even a better possibility for research reserves, but the depletion and modification of the Yellowstone fauna, already outlined, would affect any research reserves anywhere within the park so as to make them hardly more fruitful areas of study than any other area within the park.

Mount McKinley may have better possibilities for research reserves, but the great interior portion of the park is covered with glaciers, and any research reserve would have to be located on the lower fringe of the park, which is subject to the influences of immediately adjacent civilization. It may be said that civilization has already arrived at the gates of Mount McKinley.

II. The constant flux of nature, which over vast areas throughout long periods of time strikes the so-called "balance", becomes an entirely different thing in the relatively small area of a national park with everything upset around it and many of its species of wildlife either gone or nearly gone from within it. To take a specific case: When the last nucleus of the trumpeter swan nests in the Yellowstone region; when the most valuable protected breeding ground for this bird is on the Mirror Plateau, which is a research reserve; when the swan's enemies (at least, coyote, raven, crow) have increased and profited by civilization so that the swan-predator abundance ratio is vastly more in favor of the predator than it was in primitive days; then to suggest allowing the normal flux of nature to take its course means to let the man-made flux of nature drive the trumpeter swan out of existence. It would mean to give up several rare species because we did not practice wildlife management to compensate for the adverse factors which civilization has brought up against these forms of wildlife.

Does all this mean that we should abandon the attempt to preserve primitive nature simply because its normal processes have been wrecked, and should turn to management of wildlife toward building up arbitrary and static faunal populations within the national parks? Most emphatically, no. It does mean wildlife management, but toward a specific end, and that end is the restoration of the primitive faunal condition. In other words, the primitive balance of nature is not discarded; it is made the goal of wildlife management within the national parks. To accomplish this there must be restoration of some species; there must be restoration of range by the control of certain of the ungulates in certain localities; there must be acquisition of winter ranges; there must be relief from trapping in the regions adjacent to the parks; there must be a long-time policy regarding the fixation of primitive areas within the parks, and many other management measures.

The purpose of the above discussion is to indicate that the establishment of research reserves within the national parks will necessitate a certain amount of restoration, involving a long-time program. We submit the following program toward the establishment of research areas.

1. A definition of terms (for use in a national park):

(a) Primitive area. — A primitive area is that portion of a national park or monument in which no roads nor public accommodations shall be constructed; in which trails and the necessary fire-protection devices may be constructed; and over which a wildlife progressive restoration program shall be exercised. The entire body of a national park or monument, aside from road and development areas, should be for all time a primitive area.

(b) Research area. — (NOTE.—Inasmuch as insect infestations and fires might gain too much headway with a research reserve if they were not controlled, and since preparation for and the prosecution of such control has been prohibited in treatment prescribed for a research reserve, we suggest that the term "research reserves" be supplanted by the term "research areas", and that research areas shall be accorded a treatment differing somewhat from that previously prescribed for research reserves.)

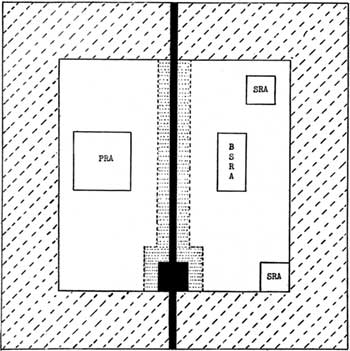

Figure 61. | |

| Black: Road and development area. Dotted: Indefinite extent of human influence modifying wilderness conditions somewhat along roads and development center. Hatched: Buffer area surrounding the park. | PRA:

Permanent research area. BSRA: Biotic succession research area. SRA: Specific research area. White: Primitive area – rest of the park. |

The character of a research area shall be identical with that of a primitive area, except that no fish culture shall be permitted within a permanent research area, or within waters which would affect or modify the aquatic life within the waters of a permanent research area.

Since research areas such as those in Lassen are valuable for various types of study but can make no pretense of conserving unmodified the larger game animals, we suggest that the single concept of "research areas" be further amplified to specify the purpose of each different type of research area, namely:

(1) Primitive research area. — An area which would be a first-class nature sanctuary (Shelford's terminology) to remain for all time inviolate and to be located permanently at one place within a primitive area.

Such primitive research areas might be located at such places as the Mirror Plateau and the Bechler River district in Yellowstone, and in other protected and adequate localities in the other large national parks, such as Mount McKinley, Glacier, Yosemite, and Katmai National Monument. Such a primitive research area has already proved valuable on the Mirror Plateau in Yellowstone by having prevented the planting of fish in that locality, thereby saving the nesting trumpeter swans from undue molestation.

(2) Specific research area. — An area set aside for the investigation of a particular species of animal or animals or of a specific problem. Such a designation might he permanent or might terminate when there was no longer need of it.

Such specific research areas might be established, say, near the Lower Geyser Basin in Yellowstone for a study of the requirements of the sandhill cranes nesting there. If the sandhill cranes, because of topographic, climatic, or some other cause of change in habitat, should go elsewhere in the park and not return to the Lower Geyser Basin sandhill crane research area, such designation might then be terminated and a new area so designated. Specific research areas might be utilized in nearly all of the national parks and monuments.

(3) Biotic or floral succession research area. — An area set aside for the protection and investigation of biotic or floral succession in a developing or recovering biotic community. Such designation might be permanent or temporary, for instance, the Lassen Research Reserve No. 4, established to protect the biotic succession in the wake of an eruption. Forest-fire areas, flood and insect devastated areas, etc., might well be designated as biotic or floral research areas.

(4) Other designations, if and when they should become desirable.

We further suggest:

2. That there be designated certain definite and limited development areas within the national parks and that these prescribed limitations be adhered to strictly in future developments within the parks and monuments. This designation of development areas should be made in order that the remaining portion of each national park and monument may be maintained always as a primitive area to be treated as indicated under definition of primitive areas just given above.

3. That members of the Wildlife Division undertake to designate and locate suitable research areas, of the different types listed above, within the national parks and monuments.

4. That, since the research-area concept is the apex of the effort to restore and maintain the perfection of each national park and monument, the program for establishment of research areas be linked with the whole move to restore and provide adequate native habitat for the fauna of the national parks and monuments. The reasons for this are two:

(a) As a protected laboratory, the research area can be no more effective than the protection of the park in which it is situated. This has been shown to be inadequate by the loss of faunal members and the deterioration of range and habitats.

(b) In order to establish adequate protection for research areas, the erection of buffer areas around the park and the readjustment of inadequate boundaries would be far more effective than withdrawing further and further within the park. This is the vital point of this entire discussion.

Overgrazed ranges, depleted and lost habitats, abnormal deer and elk populations, and decimated and lost faunal species must be restored to somewhere near normal status by wildlife management within the parks. Details of all these steps are too numerous to present here. But such procedure is necessary to make the research areas real. We further submit in order to vitalize the concept of research areas that great effort be made at this time to procure additional winter range adjacent to the parks and monuments by the purchase of submarginal farming lands and by reallocation of territory generally surrounding the parks and monuments. Readjustments of boundaries consistent with the requirements of faunal populations must be procured. Buffer areas in which there shall be no trapping of fur bearers or hunting of rare species should be erected outside of and surrounding the national parks and monuments so that research areas, and indeed the entire primitive areas of the national parks and monuments may be made real wildlife sanctuaries wherein the native fauna may be maintained in natural habitats.

It seems to us that such a program in its entirety should be our method of procedure in attacking the problem.

1 Preservation of Natural Biotic Communities, by Victor E. Shelford, Ecology, vol. XIV, No. 2, April 1933, pp. 240-245.

REPORT CONCERNING THE CHARACTERISTICS

OF BUFFER AREAS

Submitted to the Director of the National Park Service, May 28, 1934

The following characteristics of buffer areas are proposed:

1. Each buffer strip should be several miles in depth, varying of course to suit the requirements of fauna, terrain, pressure of civilization, and other conditions imposed by the environs of each park or monument. For instance, a buffer area along the east side of Yosemite should extend far enough down the east slope of the Sierra Nevada to protect the fur bearers of that side of the park from trapping, and to protect Sierra Nevada bighorn in winter, if and when they are reestablished on the park.

2. There should be no introduction of exotics within the buffer areas.

3. There should be no trapping of fur bearers within the buffer areas.

4. There should be no predatory animal control within the buffer areas, unless it is sanctioned by the National Park Service.

5. There should be no grazing of domestic sheep within buffer areas.

6. Hunting of game animals, such as elk and deer, should be permitted within the buffer areas, where and when the National Park Service deems that such action is justified. For instance, the hunting of elk around Yellowstone and deer around Yosemite are clearly justified and desirable.

It is believed that any such buffer-area program as proposed above would be of the greatest value in restoring and preserving the wilderness aspects of the parks and monuments and properly would hold a place in any comprehensive scheme of land utilization for conservation purposes.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/2/part2-3.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016