|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 5 The Wolves of Mount McKinley |

|

CHAPTER THREE:

DALL SHEEP

Description

ALL THE ALASKA SHEEP have been referred to as Ovis dalli dalli, except those found on the Kenai Peninsula, which have been described as Ovis dalli kenaiensis. Only slight skull differences separate this latter form from Ovis dalli dalli.

The Dall sheep is smaller than the Rocky Mountain bighorn (Ovis canadensis canadensis), has more slender and gracefully curved horns, and is white in color. On a dark background Dall sheep appear to be pure white, but in the snow they are seen to be slightly yellowish. Live rams average slightly less than 200 pounds in weight and the ewes are not quite as heavy.

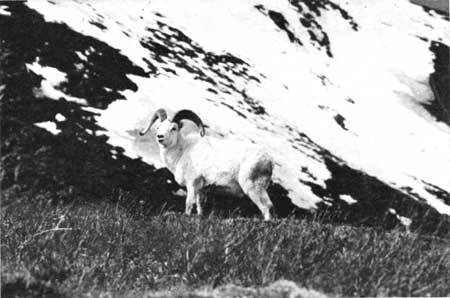

Figure 17: Dall sheep ram. [Toklat

River, May 21, 1939.]

Distribution of Dall Sheep in Alaska

Dall sheep, found in Mount McKinley National Park, are widely distributed over the mountainous regions in Alaska. They are found throughout most of the Alaska Range, in the Nutzotin, Wrangell, and Chugach Mountains, on the Kenai Peninsula, in the Endicott Mountains north of the Arctic Circle, and a few still occur in the Tanana Hills. Their range extends into Yukon Territory where they intergrade with Ovis d. stonei, a subspecies which differs from the Dall sheep mainly in color. Locally, the sheep have been reduced in numbers, or eliminated by hunting, but still they are found over most of their ancestral ranges. Sheep are reported to be still plentiful in the Wood River and Mount Hayes district of the Alaska Range, in the Endicott Mountains and on the Kenai Peninsula. In some areas, such as Rainy Pass, they are reported less abundant than formerly. However, on most of their range the actual status of the sheep is not well known.

History of the Sheep in Mount McKinley National Park

The history of the Dall sheep in Mount McKinley National Park, so far as we know, goes back over a stretch of many thousand years. It would be intensely interesting to know the detailed history of the sheep—the many vicissitudes during this long period. But through it all the sheep have survived. There probably have been many periods of sheep abundance, and many periods of sheep scarcity. During a series of easy winters, the population probably built up and overflowed the rough country into the lower gentle hills. Wolf populations may have had their own periods of scarcity and abundance, and, depending somewhat on the status of the caribou, preyed extensively upon sheep at times, or affected them little. When hares disappeared, leaving the lynx population stranded, no doubt the lynx in desperation hunted sheep. The history is an ever changing mosaic. It is to make possible the continuation of this natural course of events that Mount McKinley National Park has been established.

From 1906 to 1923, when I first visited Mount McKinley National Park, the sheep population was consistently high although there was considerable sheep hunting in the area up to 1920. Charles Sheldon (1930) found sheep abundant during his days there from 1906 to 1908. An "old-timer" told me that in 1915 and 1916, when he had hunted sheep in the area, they were very abundant, and that one winter he had sold 42 sheep carcasses. At this time several other market hunters operated in the region. Many sheep were apparently killed for the market and many were fed to the sled dogs used in hauling the meat. At an old crumbling cabin on East Fork River I found many old ram skulls, most of which were heaped in a pile. There were 142 horns, so at least 71 rams had been brought to this camp. The skulls had been split open, probably to make the brains readily available to the dogs.

Figure 18: Heap of 142 ram horns at the

ruins of a hunter's cabin on East Fork River. This indicates the extent

of hunting in the early days before establishment of Mount McKinley

National Park. [July 1939.]

O. J. Murie in 1920 observed a market hunter operating at Savage River. The hunter had shot a number of sheep on these slopes. At that time many sheep were wintering on the ridges south of Savage Camp.

In 1922 and 1923 I observed sheep summering in considerable numbers at the head of Savage River where now scarcely any are to be found. In 1923 they were plentiful but probably not as plentiful as during the next few years because extensive market hunting had stopped only 2 or 3 years before.

From 1923 to 1928 there was a steady increase in the population. Some think the peak was reached in 1928. The numbers were estimated at 10,000 and upward. Two rangers estimated the population as 10,000 and another member of the park force estimated it as 25,000. No organized counts were made so far as I know, so it is hard to evaluate the estimates. Nevertheless the population in 1928 was no doubt large. With so many sheep occupying the ranges there was not sufficient food for all among the cliffs so that many wintered on gentle slopes and down along the river banks 4 or 5 miles from the mountains. The animals were forced into the lower hills and valleys to feed. On some ridges there were patches of dead willow which I presumed had been killed during the high density of the population. I feel confident, from all the information I have been able to gather, that there were at least 5,000 sheep in the park during the peak. How much larger the figure was it is difficult to say, but it is possible that there were as many as 10,000, as some have estimated.

During this period the history of the wolves is briefly as follows: In 1906—8 Sheldon (1930) found wolves among the caribou herds but few among the sheep. He observed two different wolves hunting sheep in the Toklat River region. Possibly they hunted more to the east of Toklat River, but apparently there were only a few wolves among the sheep. John Romanoff, who hunted sheep in the park in 1915 and 1916, said he did not see a wolf track in the area at that time. In 1922 and 1923 my brother and I saw no wolf signs at Savage River, nor had my brother seen any wolf tracks on a trip up Toklat River in December 1920.

Former Superintendent Karstens in his monthly report for December 1925, mentions the presence of wolves in the park and that they seemed to be on the increase. The wolves were not considered abundant in 1926 and 1927, but in 1928 it was felt that there had been a decided increase. From 1928 to the present time wolves have persisted in the sheep hills, apparently in fair numbers. No one knows what variation has taken place in the wolf population during this period. One ranger estimated 50 wolves in 1929—30 when he felt wolves were at their peak. I estimate the 1941 population at between 40 and 60 wolves in the sheep hills. The population may not have varied greatly from that figure during the last 10 or 12 years.

There apparently had been no severe winter during the time the sheep herd built up, although some sheep apparently were adversely affected by winter conditions at times. One of the rangers captured a ewe in the deep snows of Sable Pass in 1927 and the animal died a few days later. A weak ram found at the same time but not brought in was dead when seen again.

The snow conditions in the winter of 1928—29, according to reports, caused quite a large loss among the sheep. The Park Superintendent's report for March 1929, describes conditions as follows: "The winter has been a hard one on sheep with the deep snow and storms. They have been driven down from the ridges and into the deep snow of the flats in their effort to get feed. They were even noticed out on the flats near the north boundary 4 miles from the range."

In the April report the following statement is found: "The month of April proved to be the hardest one of the year for sheep. Very few places were kept blown bare by the wind. What few bare spots there were, were soon grazed off and the sheep ranged into the flats in search of feed. It is believed that many sheep starved to death. In the vicinity of Igloo the rangers picked up three rams and three ewes with lamb, though one of the ewes was too far gone to recover and died after a few days."

The account is continued in the July report for 1929: "Nyberg and Myers returned from a trip into the mountain [McKinley] on the 27th and reported that the wild sheep in the park look to be about as numerous as ever notwithstanding the hard winter and heavy snows, and report that most of the losses occurred in deep passes where they were marooned in the heavy snow and blizzards of March and April."

One ranger wrote me that the wolves had killed many sheep that winter, but that "the big jolt" had come in April, when heavy snows covered the food. For the part of the range he had investigated near Headquarters he estimated that a third of the sheep population had died. He said that those sheep that perished were mostly the old and the yearlings.

In the spring of 1929 there apparently was a fairly good lamb crop. The following two winters were not severe, but heavy wolf predation on the large sheep population was reported.

The most serious reduction among the sheep apparently took place in the winter of 1931—32, which was much more severe for the sheep than that of 1928—29. The Park Superintendent's report for December 1931 states that the rangers were experiencing difficulty in making patrols because of the heavy snows and that "from all indications the sheep are going to have a hard time finding forage this winter." The January 1932 report states that the month was very cold, that the sheep were all in good condition, but that the late snows had driven them well up toward the summits of the mountains. In February 1932 it was reported that all records for snowfall had been broken, that 72 inches had fallen in 6 days, and that the winter of 1931—32 would be remembered as the "year of the big snow." The Superintendent reported: "During the heavy snowfall which came on the 3d of the month, I was alone at headquarters and taxed to the utmost in shoveling snow from the roofs of the buildings. It was thought for a while that several would go down, as the snow was 4 feet deep in places. I called up on the phone to get a man from the station to come up and help me out. He left there at 8 a. m. and arrived here at 3:10 p. m. It took him just 7 hours to go the 2 miles notwithstanding the fact that he had on a good pair of snowshoes. The heavy snows that came during the fore part of the month were followed by 2 days of rain, then below-zero weather, and a heavy crust was formed which has caused untold suffering amongst the wild animals of the interior of the park. This is especially true concerning the moose. Their legs from the knee down are worn to the bone, and each moose trail is covered with blood. It is possible to walk right up on a moose as they have not the courage or strength to run away."

In the April 1932 report, after some investigation of conditions among the sheep had been made, the following statements are found: "We have suffered a severe loss of mountain sheep during the winter as a result of the heavy snows; also the predatory animals have taken their toll. Ranger Rumohr counted 15 dead sheep while on his way in from Toklat. He examined many of the carcasses for evidence of wolf kills, but in most cases it appeared that the deaths were the result of starvation."

Former Ranger Lee Swisher wrote me that he found a great many dead sheep that spring which were not wolf kills. Dixon (1938, p. 231) reports that Ranger Swisher had told him in August 1932 that he did not believe there were more than 1,500 sheep in the park at that time as contrasted with an estimate of 10,000 to 15,000 he had made in 1929. In view of the deep snow and the severe crust, and the huge sheep population, which quickly consumed the food available on the more favorable ridges, it is not surprising that such a catastrophe occurred.

The lamb crop in 1932, probably because of the hard winter, was very poor, so that deducting normal winter losses, the numbers must have been smaller in 1933. Ivar Skarland, anthropologist of the University of Alaska, told me that in a trip into the park in April 1931 he had counted 830 sheep. In 1934 he made the same trip in April and saw scarcely any sheep, which agrees with the other reports on the reduction of the population.

For the period from 1933 to 1939 variations in sheep populations are not well known. One ranger thought the ebb was reached about 1935 or 1936. In 1939 there was an excellent lamb crop and a good survival of the yearlings of the previous year. Another ranger said he thought there were more sheep in 1939 than there had been for 4 or 5 years.

The yearling losses were heavier in the winter of 1939—40, and in the spring of 1940 the lamb crop was far below par. These losses and the small lamb crop were a definite set-back to the population. The lamb crop in 1941 was excellent, but there were very few yearlings because of the few lambs the year before. The present population is estimated to be between 1,000 and 1,500 sheep, perhaps not far different from the population in the spring of 1932, when Lee Swisher estimated the number at not more than 1,500. It appears to me that since 1932 the sheep population has not varied greatly.

That, in brief, is the recent history of the sheep in Mount McKinley National Park, so far as I have been able to outline it from available records.

Distribution of Dall Sheep in the Park

The main ranges of Dall sheep in Mount McKinley National Park lie north of the backbone of the Alaska Range where the snowfall is much less than on the south slope. In an east-and-west direction, the sheep are found from the Nenana River to Mount Eielson, about 68 miles to the west. From Mount Eielson to the western boundary there are no sheep now except for some sporadic records. Scarcity of these animals west of Mount Eielson is apparently due to the absence of foothill ranges, there being too much snow on the short high spurs coming from the main range for much winter use. West of the park, hills occupied by sheep are again found in the Tonzana River region. Along the eastern border of the park, a few sheep occur between McKinley Park Station and Windy, near the Alaska Railroad. Eastward from the park boundary, sheep distribution continues on all suitable locations throughout the Alaska Range.

Because less range is used in winter than in summer, the winter and summer distribution will be discussed separately. (The areas of year-long use and purely summer use are marked on the map on page 7.)

Figure 19: Double Mountain and Teklanika

River. This mountain is much used by sheep in summer, but is frequented

very little by them in winter. Many caribou use the pass between the two

peaks in crossing between Sanctuary and Teklanika Rivers. [May 17,

1939.]

WINTER DISTRIBUTION

In winter the sheep are found from the Nenana River to Mount Eielson, in suitable cliffs and slopes in the foothills and on the north end of a few of the spurs coming off the main range. From the Nenana River to Teklanika River sheep are largely confined to the long single "outside" or foothill ridge. The canyons through this ridge made by the Savage, Sanctuary, and Teklanika Rivers are especially suitable for winter range because of their ruggedness. Farther west, between Teklanika River and Stony River, the mountains available to sheep are a dozen miles in breadth. A depression a mile or more wide separates the "outside" range or foothills proper from the spur ridges coming off the main Alaska Range. At Savage River the tips of the spur ridges were formerly much used by sheep in winter, but this is no longer the case. Possibly the sheep had been too vulnerable to wolf attack there. At Toklat River the spur ridges which are separated from the foothills only by the gravel bars of the streams are still a part of the winter range.

The ridges on the winter range are mostly under 6,000 feet elevation and the sheep are usually found between 3,000 and 5,000 feet. When conditions are suitable they may range from a stream bed at 3,000 feet up the slope to 4,000 or 5,000 feet. At altitudes in excess of 5,000 feet food becomes scarce. As a rule there is relatively little snow on the winter range, even on the flats, although deep snows do occur occasionally. Prevailing south winds, which often become strong, blow many of the ridges and slopes free of snow. Although the prevailing winds are from the south, many north slopes also are blown bare. Much snow is blown into gullies and ravines and thus may at times impede free travel from one slope to another.

SUMMER DISTRIBUTION

When the winter snows melt sufficiently to permit freedom of travel the range of the sheep expands greatly. Many then move nearer the main Alaska Range, some going to the heads of glacial streams. In mid winter the snow is too deep in these regions to permit their use. Not all the sheep make these movements, for during the summer some sheep may be found over much of the winter range. Thus, on the winter range near East Fork, between 100 and 200 rams and some ewes may be found throughout the summer. Many of these rams have moved into the area from other parts of the winter range. There is apparently considerable movement by those sheep which summer on the winter range. Sheep are found all year in some numbers on Sable, Cathedral, and Igloo Mountains, and on winter range along the Toklat River as far north as the last canyon. The exclusive summer ranges are slightly higher in elevation.

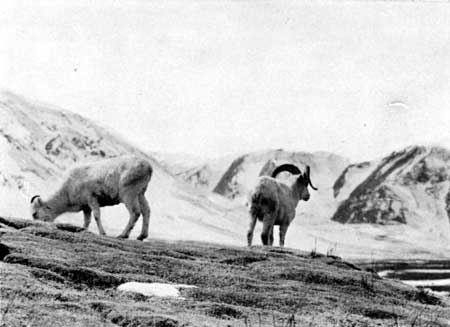

Figure 20: Some of a large group of rams

that spent the summer on the hills along East Fork River. This is also a

winter range. [July 15, 1940.]

Migration

The movements to the summer range take place during much of June and sometimes as late as July. The return to the winter range begins in August, but most of the fall migration takes place in September. Stragglers have been seen migrating in early October.

Although many details concerning the migrations are not known, a number of observations were made of the general movements. Sheep wintering on the outside range near the Nenana River apparently summer in some of the mountains on the west side of Riley Creek. They were seen crossing to the winter range in late August at Mile 5. Some of the sheep at Savage Canyon cross a mile or more of low country and follow the ridges to the head of Savage River. Some of these sheep were seen moving southwest toward Double Mountain and others may go to Sanctuary River before going southward. Most of the sheep wintering in Teklanika and Sanctuary Canyons move south 9 or 10 miles to Double Mountain and points beyond. Some of the sheep wintering on the hills west of Big Creek go eastward to Double Mountain by way of Igloo and Cathedral Mountains. Sheep from the hills west of Sable Mountain and the head of Big Creek and possibly from lower East Fork River move eastward to Cathedral Mountain and cross the Teklanika River to Double Mountain and ridges between the forks of Teklanika River. This is a pronounced movement.

Some sheep summer at the head of the east fork of the East Fork River but I do not know where they come from. They could come from the East Fork or Toklat River winter ranges. Some of those wintering on the Toklat River move to the heads of the two forks of the Toklat 7 or 8 miles beyond the boundaries of the winter range. The few sheep on Stony Creek move to the head of the creek, and those wintering in the cliffs across from Mount Eielson move 8 or 9 miles to the vicinity of Sunshine Glacier.

Figure 21: Looking up to the head of the

east branch of the Teklanika River. This is mountain sheep summer range.

Vegetation, especially grass, is sparse in these mountains. [May 17,

1939.]

Before venturing a crossing over low country the sheep may spend hours looking over the region from the slopes, apparently to be sure the coast is clear. Sometimes they may spend a day or two in watching before making the attempt. Often ewes and rams move across together in a compact band.

The sheep at Sanctuary and Teklanika Canyons have 3 or 4 miles of low, rolling country to cross to reach the hills adjoining Double Mountain, their immediate destination. Three or four well-defined migration trails lead across the low country.

On June 7, 1940, a band of about 64 sheep, both ewes and rams, crossed from Sanctuary Canyon to the low hills adjoining Double Mountain. They started crossing about 2 p. m., and did not arrive at the hills until 5:30 p. m. Most of the way the sheep traveled in a compact group, stopping frequently to brook ahead. Through tall willows and scattered spruce woods they walked in single file. Just before reaching the first hills they fed for about 15 minutes on the flats at their base. They probably were all hungry and came upon some choice food. When they emerged from the woods to the open hills they were strung out considerably and galloped up the slope in high spirits, seeming relieved to have made the crossing.

On July 27, 1939, eight sheep made a belated migration from Sanctuary Canyon to the hills north of Double Mountain. From these hills I saw a group consisting of two old ewes, two lambs, and two yearlings, one 2 year-old ram, and a young ewe coming across the flats, alternately galloping and trotting, and occasionally stopping briefly to look both ahead and behind. I lost sight of them as they approached the hills to one side of me but presently I saw them cross a creek and climb a long slope to the south. They disappeared over the top but in a few minutes all eight sheep reappeared in precipitous flight and galloped down the slope with miraculous speed and abandon. The lambs kept up with the others. They passed within 30 feet of the place where I crouched in the willows so I could see clearly how they panted hard with open mouths. They climbed a slope north of me and stood above some cliffs surveying the terrain they had crossed. No pursuer was seen but it appeared they had been badly frightened. Later they regained their composure and fed and rested.

When sheep cross a valley they often follow an old rocky stream bed even though the travel would be much easier on the sod beside the stream. They probably have an instinctive feeling of safety when traveling among boulders even on level terrain since such terrain resembles the cliffs where they are safe. This instinct for seeking the boulder-strewn country on the level would serve a good purpose if such areas were extensive enough so that an enemy could not follow on firm smooth sod close by, as they can along the stream beds. On one occasion two ewes which were captured by wolves might have escaped if they had not followed a rocky stream while the wolves ran on the firm sod alongside the rocks.

In migrating along ridges where there are cliffs the sheep move leisurely, frequently stopping in places for a day or longer to feed. Sometimes they may remain on a mountain along the way for a week or more. A band of about 100 ewes and lambs fed on Igloo Mountain for a week before continuing their migration. They moved slowly around the mountain in their feeding, some days going only 300 or 400 yards. Sometimes a band will retrace its steps a half mile or so before going forward again. The movements in both spring and fall are similar. although the fall migration may at times be hurried a little by snow. However, the sheep frequently begin their fall movements before the coming of heavy snows. Single animals, or bands containing up to 100, may be seen in migration.

Figure 22: Looking southward up Igloo Creek

to Sable Pass, a much-used caribou migration route. The mountains in the

foreground are grazed by sheep the year around. The distant ridges are

spurs of the Alaska Range. The highway can be seen along Igloo Creek

(lower left). [May 17, 1939.]

The causes of migration are difficult to determine. Vegetation influences migration at least to the extent that it must be satisfactory on the range sought by the sheep. Grazing animals will often follow the snow line in spring as though they were seeking the tender new vegetation. This may be partly a cause-and-effect relationship, but, at least in part, it may be purely an incidental correlation; in following the snow line the animals may simply be driven by an urge to return to a remembered summer habitat, and not necessarily because of the seasonal stage of the plant growth. In Mount McKinley National Park it was not at all evident that the sheep were following very closely the appearance of new vegetation. Near the glaciers, where some of the sheep go, it is true the plant growth is much later than on parts of the winter range, but in many cases the growth stages of vegetation on winter and summer habitats are quite similar. On north slopes, especially, the growth on winter range is late and is green and succulent all summer. Indeed, in some respects the food on winter range seems better than on purely summer range. On winter range there is more grass and a greater variety and abundance of plant species. On the other hand, many of the species that are especially attractive to the white sheep occur on the purely summer ranges in quantity that is ample for their needs. If the migration were a complete one from winter to purely summer range, with no exceptions, one might conclude that the summer range was preferred and was not utilized in winter because of deep snows. This may still be true to some extent. A detailed study of the vegetation over all the ranges might reveal some interesting correlations.

We may assume that migratory habits had a beginning in the racial history of a species. At such an early period the sheep may have remained on the remote summer ranges until driven out by snow. Then, after such a movement had become habitual and more or less punctual, it is reasonable to assume that their fall migration might anticipate the coming of the snow. Or, the inception of the fall movement may be due to the deterioration of vegetation (by ripening and drying) on the purely summer range, for the sheep usually begin to move before the snow drives them out.

Figure 23: Excellent all-year Dall sheep

range along East Fork River. [July 15, 1940.]

Insects are often stressed as a factor causing migration of big game and no doubt do at times influence local movements. Occasionally flies annoyed the sheep and caused them to seek the shade of cliffs, but usually the flies were not much in evidence, probably because of the cool breezes on the ridges. Since insects are relatively scarce on purely summer and winter ranges, it seems unlikely that any difference in their incidence would be sufficient to cause migratory movements. As suggested above, the insects might cause local movements such as from one side of a ridge to the other or from the sunshine into the shade.

One factor which may be of importance in explaining the migrations is the natural tendency of animals to wander. Let loose some horses and they will wander widely in their grazing. In any area the sheep wander about considerably over a period of days. Repeated wandering movements to certain localities may in time have established definite migration habits. In other words, the sheep may migrate simply because they like to travel.

The factors originally causing the movements of sheep may have disappeared, so that the animals may now be migratory largely because of habit which has no present-day use. When the population was excessively large, as it was in the late 1920's and often has been in the past, the sheep may have moved from an overgrazed winter range to the fresh pastures unavailable in winter. Now that there is no need for fresh pastures, the sheep may continue their treks because of a habit handed down to them.

The causes motivating sheep migration require more study and careful interpretation before any conclusions can be reached.

Food Habits

The general pattern of the food habits of the sheep was established by observing their feeding, examining the vegetation where they had fed, examining stomach contents. A detailed study of the summer food habits was not made so that no doubt many minor food items are not here recorded. It was of interest to find that, although the main food consisted of grasses and sedges, considerable browse was eaten.

Figure 24: Igloo Creek is in the

foreground; the far mountains are on the other side of Teklanika River.

Sheep frequently descend to the creek bottom to feed on the willows. The

spruce in the middle distance is at timber line on Igloo Creek.

[September 1939.]

WINTER FOOD HABITS

Much of the information on the winter food habits was secured from the analysis of the stomach contents of sheep which had died on the range. The stomach contents of 75 sheep were analyzed. Of these, 54 had died in winter when no green grass was available, and 21 had died during the fall and spring, when a small amount of green grass was to be obtained. Since the only essential difference between the two series is the presence of some green grass in one of them, they have been combined in Table 3, page 76. Seventeen of the stomachs were from rams, 26 from ewes, 2 from lambs, 5 from yearlings, and 25 were undetermined.

Since most of the sheep from which these stomachs came were old or diseased it is possible that the contents are not entirely representative of the entire population. Healthy sheep might wander down in the bottoms more to feed on willow or sage, and weak animals probably would not move about a great deal in search of variety. However, the series of stomachs probably gives a fairly good picture of the winter food habits.

TABLE 3—Results of food analyses of 75 Dall sheep stomachs collected in Mount McKinley National Park, from animals that succumbed in autumn, winter, and early spring.

| Plant species | Number of stomachs in which item occurred |

Percentage | |

| Average volume |

Maximum volume | ||

| Grass and sedge | 75 | 81.5 | 100 |

| Equisetum arvense | 4 | 48.0 | 96 |

| Blueberry, Vaccinium uliginosum | 8 | 14.9 | 60 |

| Willow, Salix spp | 63 | 10.2 | 75 |

| Sage, Artemisia hookeriana | 20 | 5.4 | 35 |

| Cranberry, Vaccinium vitis-idaea minus | 30 | 4.6 | 70 |

| Crowberry, Empetrum nigrum | 14 | 2.7 | 30 |

| Dwarf willow, Salix reticulata | 2 | 1.0 | 2 |

| Lapland Rose-bay, Rhododendron lapponicum | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Loco, Oxytropis spp | 7 | .8 | 5.0 |

| Labrador tea, Ledum sp | 3 | .6 | 1.0 |

| Dwarf Arctic birch, Beluta nana | 2 | .5 | 1.0 |

| Mountain avens, Dryas spp | 19 | .4 | 3.0 |

| Lichen, Cladonia sp | 4 | .12 | /5 |

| Saxifrage, Saxifraga tricuspidata | 13 | .08 | .5 |

| Moss | 2 | Trace | Trace |

| Alpine azalea, Loiseleuria sp | 2 | Trace | Trace |

| Cinquefoil, Potentilla fruticosa | 3 | Trace | Trace |

| Leaf lichen | 2 | Trace | Trace |

| Alder, Alnus fruticosa | 1 | Trace | Trace |

| Bearberry, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi | 1 | Trace | Trace |

| Aster, Aster spp | 2 | Trace | Trace |

| Pyrola sp | 1 | Trace | Trace |

An annotated list of the foods known to be eaten by the sheep in winter follows:

Grasses and Sedges.—The principal winter food of the mountain sheep consists of grasses and sedges. Every stomach contained some grass, and the average amount present was 81.5 percent.

in the middle of September, when the ground was covered with 14 inches of snow, and again in October after a heavy snowfall, I noted, in following trails, that the sheep were feeding extensively on the seed heads of Calamagrostis canadensis, C. langsdorfi, Festuca rubra, Agropyron latiglume, and Trisetum spicatum. Heads of other grasses are perhaps also eaten. Such feed must be very nourishing. Considerable amounts of dry grasses were eaten by early October.

There is a good growth of grass and sedge on the winter range, and since the wind generally blows the snow off the exposed ridges, usually these foods are readily available, On the high ridges species of Poa and Festuca form much of the grass cover. Along with these highly palatable grasses there is a much-utilized short sedge (Carex hepburnii) which grows in solid stands.

Figure 25: The ewe and ram are on one of

the exposed grassy ridges which are grazed closely in winter.

[Polychrome Pass, May 17, 1939.]

Willow.—Willows (Salix spp.), both the tall and dwarf types, are eaten at all seasons. They were present in 63 stomachs and the average percentage in these was 10.2. The largest percentage found in any stomach was 75. The species of willow are not listed separately except in the case of one of the dwarf willows (Salix reticulata) which was noted in two stomachs. Some willows may be somewhat more palatable than others but several species among both the tall and dwarf varieties are highly relished.

Dwarf willows are widely distributed over the ridges, and the tall willows grow along the streams and in swales between the spur ridges, sometimes far up the slopes where the sheep can feed upon them without too much danger from wolves. Often in October and November sheep descended to creek bottoms to feed on willows. They also fed extensively on those growing in the swales between the ridges. Here in the fall they waded through 14 inches of snow in search of willow leaves that were still green. Dried leaves were also eaten at this time. Along with the leaves, twigs up to a quarter of an inch in diameter were eaten. Generally the leaves are picked off the sides of the twigs, sometimes down the twig a foot or two. Because willow is eaten so much during the early winter, I expected a higher representation in the winter stomachs, but as the snow deepens in the swales, willow probably is not so readily available.

Horsetail.—Although horsetail (Equisetum arvense) was found in only four stomachs, it is nevertheless highly relished. The species is found in swales and wet spots, and sometimes in good stands quite high up the slopes. Because of its occurrence In swales it is probably not readily available in winter because of snow. At East Fork at the base of the ridges there is an extensive stand which had been closely cropped in the spring of 1941. There were many sheep droppings on the area. In the fall after the snow appeared several places were noted where sheep had pawed for it through the snow. Two ewes killed by wolves on October 5, 1939, had been feeding in a swale on this plant when surprised. Their stomachs contained almost 100 percent Equisetum.

Figure 26: Ewes feeding in about 14 inches

of snow. They pawed readily down to grass but fed mostly on the leaves

and twigs of willows and grass heads protruding above the snow.

[Igloo Creek, September 19, 1939.]

Sage.—There are at least three species of sage which are highly palatable. Artemisia arctica and A. frigida occur scatteringly and were nowhere found to be abundant.

These sages are probably eaten in winter although none was recognized in the stomach contents. In late fall they were found much eaten. The tall herbaceous sage, Artemisia hookeriana, is highly palatable at all times. It is most abundant along streams and reaches far up the slopes in the draws between ridges. It often grows in dense clumps. In September and October, when the leaves and stems were dry, the sheep frequently fed on this herbaceous sage in the creek bottoms. Tracks at Big Creek showed that a band had crossed the creek and fed on a sage patch near the mouth of a ravine. In the high draws at East Fork this sage was uniformly closely browsed by spring. It was found in 20 of the stomachs and averaged 5.4 percent of the contents. The greatest amount of it found in a stomach was 35 percent of the contents.

Cranberry.—Cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea minus) is an abundant evergreen widely distributed over the hills. Although eaten in only small quantities, it apparently is frequently sampled. It was found in 30 stomachs. Usually only a trace was noted, but in one stomach it made up 70 percent of the contents. In October, when a variety of food was available, the sheep were several times observed feeding on cranberry.

Blueberry.—Blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) was found in eight stomachs, making up 60, 40, and 15 percent of the contents of three of them, and 1 percent of the contents in each of five others. The berries, leaves, and twigs were eaten, but the berries were especially sought. The stomach of a lamb which was killed on October 4, 1939, contained 40 percent blueberries. On that date a band had been feeding extensively on blueberries. On October 7 and 12 it was again noted that sheep had fed heavily on them. Some of the berries had been picked up from the ground. The deterioration of the berries as the season advances, and their reduced availability because of snow, probably is the explanation for the relatively few stomachs containing blueberry in the winter.

Crowberry.—Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) was present in 14 stomachs, making up 30 percent of the contents of one stomach, but on the average comprising 2.7 percent of the contents. The twigs and leaves of this evergreen were found in the stomachs, but very likely the berries were also eaten, It was found browsed in early October. Perhaps it would be eaten more extensively if it were more abundant on high ridges and grew taller. Crowberry is most plentiful on the lower slopes.

Figure 27: A swale, between lateral ridges

of Igloo Mountain, where sheep often fed in the fall on the willow which

protruded through the snow. [September 19, 1939.]

Mountain Avens.—Mountain avens (Dryas spp.) was found in 19 stomachs averaging 0.4 percent of the contents. There are about five species of dryas in the park. Some grow mainly on the old river bars where they form extensive mats, while others are found on the ridges. The principal cover of many slopes is dryas, consequently these slopes are poor winter range for sheep. Because it is much eaten in summer it has sometimes been referred to as an important winter food. However, in winter it becomes dry and brittle and loses much of its palatability.

Loco.—Loco (Oxytropis) was found in seven stomachs. Some species were highly relished in the fall while the leaves were still green. The remains found in the stomach contents consisted of the basal part of the plant nipped off at the root. Dry leaves may have been present in other stomachs and escaped detection.

Hedysarum.—Both Hedysarum americanum and H. mackenzi are highly relished in the fall but none was found in the stomachs. The seed pods were often noted eaten in September.

Dwarf Birch.—Dwarf Arctic birch (Betula nana) was found in only two stomachs, The leaves and fine twigs of dwarf birch were noted eaten in late September. It is not readily available on the high ridges.

The following species were found in the stomachs in small quantities: Saxifraga tricuspidata, Ledum groenlandicum, Loiseleuria procumbens, Potentilla fruticosa, Rhododendron lapponicum, Alnus fruticosa, Arctostaphylus uva-ursi, Aster sp., Cladonia sp., leaf lichen sp., and moss.

The following species were found eaten in late fall: Heracleum lanatum. (seed heads and leaves), Delphinium sp. (when dry), Shepherdia canadensis (mainly berries), and Mertensia sp.

SUMMER FOOD HABITS

In summer, as in winter, the principal food of the sheep Consists of grasses, sedges, and willows. However, at this season much Dryas is also eaten, and a variety of other species are eaten in small amounts. Frequently sheep were seen feeding on the leaves of willow. For example, on June 11, 1940, 36 sheep fed steadily on two species of willow for 40 minutes, and on June 20, 1940, a band fed for a half hour on willows. On some of the higher slopes where the shrubby willows are absent there is an abundance of dwarf willows only a few inches high which are grazed extensively. Some species of Oxytropis and Hedysarum are much sought. The leaves and flowers of herbaceous cinquefoil, Aconitum sp., Campanula lasiocarpa, Arnica, and Conioselinum. were eaten.

The contents of one stomach, that of a 2-year-old ewe that died on June 8 as a result of a snag injury, were available for analysis. The following determinations were made: green grass, 85 percent; willow, 14 percent; Oxytropis sp., trace; Pyrola sp., trace; and Salix reticulata, trace.

MINERAL LICKS

Sheep were often seen at licks, and well-defined trails led to some of them. A lick on Ewe Creek was much used, and two in Teklanika Canyon, similar to the preceding, were used extensively. On East Fork the sheep visited a lick on the side of the slope where water seeped out. The mud in this lick was black, while in some of the others the material was gray. On Double Mountain a lick was used by both sheep and caribou. On Toklat River two licks were also found in use.

Above the Ewe Creek lick many sheep droppings were found which were made up entirely of clay, so it is evident that considerable quantities of the earth are eaten at times.

Dixon (1938, p. 223) had samples of the Ewe Creek lick analyzed by Dr. G. L. Foster of the Division of Biochemistry, University of California. He reported that calcium and iron phosphate were the two minerals present in the lick which would be soluble in digestive fluids. Insoluble substances, chiefly magnesia and silicates, were also present.

Carrying Capacity of the Winter Range

After observing so many overgrazed big-game ranges in the States it was a pleasant experience to find the sheep range in Mount McKinley National Park not overutilized. By spring the grasses on the more accessible ledges are closely grazed but they are not harmed even in these places where grazing is concentrated. Willows are not now overutilized, although in years past, when sheep were more abundant, patches on the ridges were killed off by overbrowsing.

There are now from 1,000 to 1,500 sheep using the winter range which comprises an area of between 200 and 250 square miles. But of course not all of this area is a source of food. Many cliffs and rock slides support little growth; the vegetation on many slopes, ravines, and stream bottoms is deeply covered with snow; and extensive areas have a cover which is mainly Dryas, thus furnishing little winter grazing. Hence, without an extensive survey of cover types, it would be difficult to determine the amount of range actually available to the sheep in winter, and this amount would fluctuate from year to year because of varying snow conditions.

Figure 28: Cathedral Mountain in foreground;

south extension of Double Mountain on center sky line. Dryas

predominates on so many slopes that Cathedral Mountain is a rather poor

winter range for Dall sheep. [September 1939.]

The carrying capacity of the winter range is several times the number of sheep now present in the park. As will be discussed later in detail, it is the wolf, rather than the food supply, that appears to be the chief factor limiting the size of the sheep population. The wolf reduces the size of the sheep range by confining sheep to the more rugged country where they are less vulnerable to wolf attack than elsewhere.

In the rugged country, the wolf preys on the sheep sufficiently to keep them below the carrying capacity of the range as determined by food supply. Thus the present sheep numbers apparently are dependent on the extent of cliff protection and the degree of wolf pressure.

Disease and Parasites

ACTINOMYCOSIS

From an examination of the skulls, it is obvious that the sheep are subject to two diseases, common among big game animals, which are known as actinomycosis and necrotic stomatitis. These ailments are described in detail on p. 117. Much of our information on necrotic. stomatitis was secured among the elk in Jackson Hole, Wyo., where it was also found among the deer, bighorns, and moose. In the case of elk, many calves are subject to it. Death among them is often rapid, occurring before the lesions have affected the bone tissue. Many older animals which have recovered are often left with serious dental deformities or loss of teeth. The annual loss among the elk due to necrotic stomatitis apparently becomes more severe during years of food scarcity. The data available indicate that the Dall sheep may be affected by this disease in a manner similar to the elk. The annual loss due to this disease is not extensive.

LUNGWORM

In the lungs of a yearling collected April 24, 1939, and examined by Dr. Frans Goble, numerous eggs, larvae, and adults of a nematode were found which apparently belonged to the genus Protostrongylus or a close ally. (Goble and Murie 1942.) This is the first record of lungworm in the Dall sheep, but the parasite is probably common among them. Lack of previous records is probably due to lack of material for examination. Lungworms might affect the health of some animals, but no data on this were secured. Coughing, so prevalent in the sheep in Yellowstone National Park and Jackson Hole, Wyo., was not observed.

SCABIES

No animals were seen which showed any evidence in the appearance of the coat that scabies existed among them. No mites were found in patches of hide examined. Scabies is quite prevalent among some of the Rocky Mountain bighorns.

A SICK LAMB

About the middle of June 1940, a sick lamb with its mother was seen by a ranger at a tributary of Igloo Creek on the east side of Sable Pass. The lamb was too weak to walk, and saliva drooled from its mouth. It was carried to the creek where it was seen the following day, unable to rise. When I learned about the incident the lamb was gone.

LAMB DIES IN CAPTIVITY

In April 1929, three weak ewes were rescued from starvation. Two lived and gave birth to lambs at Park Headquarters. One of the lambs did very well, but the other died on the second day after it was born. When it was discovered that the ewe had no milk it was too late to save the lamb. Possibly this type of tragedy accounts for the loss of some lambs at birth in the wild, especially after hard winters.

INSECTS SOMETIMES ANNOY SHEEP

On a few occasions flies were observed annoying the sheep considerably. On July 26, 1940, among the rock chimneys near Sable Pass all the sheep had sought the shade to avoid the large flies which were attacking them. Sheep out in the sun, where they had moved when I disturbed them, were much troubled by these pests. In desperation they would hurry to the shade of a rock. A ewe climbing a long slope opposite me was much bothered by flies, and stopped in the shade of the first cliffs she reached. An old ram lying in the shade was directly in the route I planned to follow to climb out of some rough cliffs into which I had descended. He moved off at my close approach, but when the flies attacked him in the sun he suddenly hurried back to the shade near me. As I approached him he faced me and looked as though he might hold the passage at all costs.

On July 19, 1939, I saw a ewe stamping her foot and watching an insect buzzing around her. She dashed rapidly away, then stood perfectly still, apparently waiting to see if the fly had followed, Three times I saw this performance, in which the sheep behaved much like a caribou when attacked by a botfly.

As a rule the sheep did not seem to be greatly bothered by flies. On the high ridges there is generally enough breeze to greatly minimize this annoyance.

Mosquitoes are said to have attacked some captive sheep at Park Headquarters, but it is not probable that they are of much significance in the sheep hills, where they usually are not plentiful.

Accidents

In 1939 a number of crippled animals were observed. Strangely, no cripples were seen the following two summers except one which had been snagged and was found dead. This difference was due in part to the greater time spent among the sheep in 1939, and possibly, in part, to lighter wolf pressure on the sheep in 1939. The animals injured will be enumerated in order to give an idea of some of the accidents to which sheep are subjected and to show that there is a certain percentage of obviously vulnerable animals, and some accidental casualties.

A lone yearling was found near the road (on April 24, 1939, and it was so weak it could barely rise. When it did get to its feet it stumbled toward me (probably because I was between it and the rocks) and fell at my feet. The hoof of one forefoot was elongated, showing that it had not been used for a long time. One rib was broken and the area around it festered and bloodshot. Other spots showing serious suppuration were the injured foot and the knee, and two spots along the spinal column. There was a sore on each side of the upper palate and sores around the lips. The bruises and broken rib suggested that the yearling had fallen in the rocks.

Figure 29: A yearling sheep, whose right

foreleg had been injured, apparently by a fall. The foot had been so

little used that the hoof had grown long. [Polychrome Pass, April 24,

1939.]

On May 13, 1939, a ram about 5 years old had a decided limp on a foreleg.

On June 18, 1939, a young ram on the east side of Cathedral Mountain was lame in a foreleg. When the animal fed, it either held this lame leg off the ground or rested on the knee.

A ram about 6 years old, observed at East Fork on June 27, 1939, had a horn which, instead of curving outward, curved toward the neck so that in time, as it grew longer, it might gouge into the top of the neck.

On July 26, 1939, a lamb was noted at the head of East Fork River which had a seriously lame foreleg.

On Big Creek on August 16, 1939, Emmett Edwards saw a lamb with a severe limp in a foreleg. On August 18 he saw a ewe with a large raw spot on the right ham which appeared to be the result of a severe bruise.

On September 11, 1939, a lamb was seen on Polychrome Pass with a long deep gash across the rear of one ham. The hair around the wound was red from recent bleeding. The cut appeared to have been made by a rock. Possibly the lamb had fallen.

On September 12, 1939 on Igloo Creek, a lamb carried a crippled foreleg, not using it at all.

On September 20, 1939 I noted an occasional drop of blood in the tracks of some sheep which had been feeding in the snow. Nothing serious, but it indicates that the feet may be come quite sore in crusted snow.

On September 29, 1939, a yearling was seen with a decided limp in a foreleg. A ewe in the same band was soiled from the tail to the ankle. In the distance it appeared to be dried blood, but of this I could not be certain. It may have been due to diarrhea.

On June 8, 1940, a 2-year-old ewe was found dead at Igloo Creek on a low slope. A snag had penetrated the abdominal cavity and the small intestine.

Some years a go a ranger found a sheep at Igloo Creek which had died from a fall incurred by slipping on a glacier.

At least two instances of sheep frozen in overflow on the rivers have come to my attention.

In September 1928, five young rams were found dead in Savage Canyon. They had died from eating dynamite.

In the Park Superintendent's report for 1927 it is stated that a ranger found the carcass of a sheep at Toklat River. When found, the carcass was fresh and there were no marks on it except where birds had picked a hole in the entrails. The tracks in the snow showed that the animal had walked off some glare ice a distance of 25 yards and had dropped dead. The suggestion is made that is may have slipped on the ice and hurt itself internally.

THE MENACE OF DEEP SNOW

The deep snows of the winters of 1928—29 and 1931—32 took a heavy toll of the sheep. Apparently in some cases entire bands, in crossing from one mountain to another, became exhausted in the valleys and died en masse. There is no detailed report on the situation but it is stated that bunches of sheep were found dead with no indication that they had been killed by wolves. Some of the sheep were no doubt later fed upon by wolves and foxes, making it impossible so know whether the animals had starved or been killed. Many of the sheep killed by wolves during these two hard winters were no doubt first weakened by snow conditions. Perhaps most of these sheep were doomed, but it is possible that some of those killed by wolves might have survived the severe weather.

In April 1927. one of the rangers found a ram and ewe in a weakened condition in the deep snow as Sable Pass. The ewe was brought to Headquarters but died a few days later. The ram was found dead when the spot was again visited.

In February 1929, when the snow was unusually deep, two rams were seen to jump on a drift of loose snow and sink completely out of sight. In such a circumstance they would be quite helpless if a predator were near.

In April 1929, three ewes and three rams were rescued at Igloo Creek in a weak condition due to deep snows. One of the ewes was too far gone and died in a few days. After the sheep had been kept a while at Igloo and regained some strength they were taken to Headquarters. They were later moved to the University of Alaska where they were kept for several years.

Ranger John Rumohr stated that in the spring of 1932 when the snows were deep he had seen 30 old rams on the low banks bordering East Fork River south of the road. Later he found five of them dead, untouched by any animal.

The deep snows have played an important role in the control of the sheep population. Probably the larger the population the more drastically are the sheep affected. A large population quickly devours the food available on ridge tops and they must all go down to the deeper snow in search of food. A smaller number might find sufficient food on the ridge tops so pull them through a severe winter. This is an example of one of the regulatory devices of Nature.

The Rut

Observations on the rutting of the mountain sheep were limited because during much of the rutting period I was checking on wolf movements along the north boundary, and snow made is difficult to cover much territory. The time of the beginning and ending of the rut was not learned. The rutting was probably early because the following spring the lambing period was early.

On November 15, 1940, I noted that the rut was in progress. On Polychrome Pass one old ram and 2 younger rams were with 5 ewes, and another old ram was very active rounding up a flock of 5 ewes. The following day considerable rutting activity was noted on East Fork River. A large ram herding 4 ewes walked a short distance to a large ram in possession of 4 other ewes. After standing around about 10 minutes he returned to his own harem just over the rise. One old ram had 7 ewes, and another was lying near a single ewe. Eleven large rams, 3 young rams, and 12 ewes were scattered over a small area observed. Some of the rams were not in possession of any ewes at the time.

Sheldon (1930) in 1907 found active rutting from about the middle of November to the middle of December. He noted several encounters between rams, and makes the following comments on the rut (p. 240); "Friendly rams remained among the ewes, serving them indifferently. The fights always occurred when stranger rams attempted to enter the bands. As times new rams intruded among the ewes and shared their privileges without apparent objection on the part of rams already with the band."

The rutting activities of the white sheep are apparently very similar to those of the Rocky Mountain bighorn. One ram may serve a number of females and two or more rams may serve the same one. The ewes come in heat over a period of about a month, but judging from the lambing time it appears that most ewes come in heat during a two-week period.

Gestation Period

In 1907 Sheldon (1930) observed the sheep actively rutting in the latter half of November and early December. How late in December active rutting took place is not known because Sheldon's observation of the sheep was interrupted by trips after moose. The following spring he observed the first lamb on May 25. In 1940 I observed sheep rutting in mid-November but do not have data on the duration of the rut. The first lamb the following spring was seen on May 8. The gestation period seems to be between 5-1/2 and 6 months.

Figure 30: Two ewes with their lambs which

are only a few days old. As young lambs remain close to their mothers,

eagles have little opportunity to attack them successfully.

[Polychrome Pass, June 3, 1939.]

Lambs

PRECOCITY

Lambs a day or two old, so small that they can walk erect under their mothers, clamber up cliffs so precipitous that even the mothers can scarcely find footing. Not only can the lambs climb but they possess unexpected endurance. Frequently very young lambs were seen hurrying after their mothers from near the base of a mountain to its very top without resting.

The travels of a captive lamb illustrate the endurance they possess. On May 13, 1928, a ranger brought to his cabin a lamb only a few hours old. It soon became a pet and amused itself by leaping about on the chairs and beds. It followed him and his cabin mate around all day and showed no desiretso join the other sheep that were sometimes in view. It was raised with a bottle, on powdered milk. When only 2-1/2 weeks old it followed the men for 30 miles over rough ground and through glacial streams. When a month old is became wet in a glacial stream when overheated and died of "pneumonia."

It surprised me when I first observed the speed of the lambs on relatively smooth slopes. On May 28, 1939, when most lambs were a little less than 2 weeks old, I came suddenly upon six or seven ewes and their lambs. My nearness gave them quite a fright, causing them to flee full speed down a gentle slope to the bottom of a draw and up the other side. Although the ewes galloped at full speed, the lambs kept up easily and at times two or three of them even forged out ahead. Upon reaching the bottom of the ravine and starting up the other side, the lambs seemed to have an advantage and "flowed" smoothly up the slope ahead of the ewes. When the group finally stopped to look around the lambs were as fresh as ever, and seemed anxious to make another run. This precocity of the lambs is, of course, of great value in avoiding wolves and other predators.

Figure 31: Ewes with lambs frequently

congregate on rugged cliffs when the lambs are young. When they go off

to feed, some ewes leave their lambs in the care of other females.

[Polychrome Pass, May 1939.]

EWE-LAMB RELATIONSHIPS

During the first week or two, ewes that have lambs are especially wary. When approached, they hurry off with their lambs, often crossing over to another ridge so as to leave a draw between them and the intruder, or else climb high into rough cliffs. Before the lambs are born these same ewes might be rather tame, and as the lambs become older they again become tame.

The lamb is not left lying alone as are the young of deer, elk, and antelope. It remains near its mother, pressing so close to her at times when traveling that it may be almost under her. When resting, the young lamb usually lies against the mother or only a few feet away. This habit of remaining close to the mother is of high protective value should eagles attack.

When the lambs are young, several mothers often congregate in rough cliffs. In such places a few of the ewes may remain with the lambs and the others go out 300 or 400 yards to feed on the gentler slopes. On May 26, 1939, 13 lambs were seen frisking about on some cliffs on a rocky dike on East Fork. With the lambs were 6 ewes—3 lying down just above the group, and 3 standing in their midst. While I watched, one of the ewes moved off 150 yards and commenced to feed. A lamb followed her 10 yards, then dashed back to the others. One lamb ventured out alone 20 yards and a ewe at once became alert and moved four or five steps in its direction, whereupon the lamb hastened back to the group. Four ewes were feeding on a slope about 250 yards away from the cliffs. Occasionally one of them would look toward the lamb assemblage. From a point about a quarter of a mile away three ewes stopped feeding and came galloping across the face of a shale slope, calling loudly as they came. When they were still about 100 yards away two lambs galloped forth, each joining its mother and nursing at once. The third ewe did not have such an alert or hungry lamb, for she smelled of five lambs in the top group, then walked briskly down to the rest of the lambs 15 yards below where she found her lamb, who belatedly came forth to nurse.

Figure 32: A ewe and her lamb in the fall

of the year. [Polychrome Pass, September 7, 1939.]

On June 5, 1939, there were 22 lambs on this outcrop of cliffs and an equal number of ewes were seen, but some of the ewes were feeding 200 or 300 yards away. One lamb on this occasion ran out about 60 yards to meet its mother and to nurse.

On July 12, 1939, a band of 52 ewes, lambs, and yearlings were feeding on some rather gentle slopes of Cathedral Mountain. The mothers frequently moved off 100 or 200 yards from their lambs which remained in a scattered group resting on the slide rock. Five or six ewes at different times stopped feeding and called loudly. Each time, a lamb would recognize the call of its mother and gallop down to nurse, usually for a minute or less. The sheep were quite noisy at times, the ewes "ba-a-ing" loudly, and the lambs answering more softly.

The tendency for ewes with lambs to bunch up is probably a natural outcome of their all having the same inclination to remain in the rougher terrain. Later there is more intermingling of the ewes with lambs and those without lambs.

Figure 33: A band of ewes, lambs, and

yearlings on Cathedral Mountain. Vegetation on the loose slide rock is

dominantly dryas. A wide variety of herbs and some grass are also

present. Note how some of the lambs remain close to their mothers.

Others rested alone while their mothers fed lower on the slope. [July

12, 1939.]

LOST LAMBS

When a ewe leaves her lamb in a group and goes off to feed she may lose her lamb temporarily. On June 7, 1940, I climbed to a small group of ewes and lambs which ran out of sight when I neared them. I was standing on the spot where they had been, when a ewe, which I had passed on the way up, approached me calling. There was not much room on the cliff where I stood so, when the ewe was seven or eight paces from me, I stepped to one side to let her pass. She was evidently perturbed at finding me where her lamb had been, for she called loudly and came toward me with lowered head which she jerked threateningly upward as though to hook me with her sharp horns. After I had warded her off with my tripod she stood for a few moments calling, then hurried in the general direction the others had taken and no doubt soon found her lamb, for the band had not gone far.

On June 13, 1941, I spent some time on Igloo Mountain observing about 50 ewes and 30 lambs. At first most of them were in a broad grassy basin. One ewe nursed her lamb, walked off 200 yards and fed with another ewe for an hour, never once looking toward the lamb. As I climbed, a small group of ewes and lambs, including the lamb of one of the two feeding ewes, moved upward, feeding higher and higher until they were out of my view. When the two ewes rejoined the main band which in the meantime had moved 200 or 300 yards to some cliffs, one of them found her lamb at once but the other was not so fortunate. Calling continually, she searched through the entire band, duplicating her visits to some parts of it, but still with no success. She finally recrossed a gulch and climbed in the direction taken by the little group with which her lamb had gone. She showed good sense, and no doubt soon found her lamb. After the sheep had rested in the cliffs for some time another ewe suddenly commenced to call at short intervals from a prominent point. The ewe had called a long time when two lambs came forth from a large crevice in a rock a short distance away where they had been lying. The ewe saw them emerge and hurried to join them. One of them was her lamb and it immediately nursed.

Figure 34: Ewe, lamb, and yearling plow through a September

snow. [Igloo Creek, September 19, 1939.]

PLAY

The lambs play a great deal, romping with speed and agility. Sometimes they butt each other, coming together after a 2- or 3-foot charge. Occasionally a ewe may play with the lambs. Once one played with three lambs, dashing after one, then another. A lamb would leave its mother, get chased, and rush back again to its parent. Apparently is was great fun.

WEANING

Lambs begin to nibble grass when they are a week or 10 days old, and as the summer progresses they feed more and more on green vegetation. Some of the lambs continue nursing well into the winter and I have seen them when they were yearlings trying to nurse. Sheldon (1930, p. 278) reports lambs nursing in February. Weaning is not an abrupt process. I expect that long before nursing is discontinued the lambs could get along very well without this nourishment. The lambs remain with the mother a year and sometimes in the case of female yearlings, another 6 months. It is not uncommon to see a ewe, yearling, and lamb together during the summer and fall. Often yearlings, 2-year-olds, and other youngish animals, along with barren ewes, may be found traveling together. In the spring male yearlings sometimes join the bands of rams.

Relation with Animals of Minor Importance

SNOW BUNTINGS COMPETE FOR FOOD

On October 11, 1939, a flock of about 100 snow buntings (Plectrophenax n. nivalis) in a high pass were feeding on the heads of Calamagrostis. A large patch had been quite thoroughly threshed by the snowbirds. Here was competition for food between animals which we would not expect to have much relation with one another. I had noticed that the sheep had been feeding extensively on these same grass heads which stuck up through the snow. Calamagrostis is a very common grass, so there is much of is available. But it so happened that the particular patch eaten by the snow buntings was up high where it would be available to the sheep when deep snows covered that growing lower down. However, this competition is no doubt extremely slight and is mentioned here only to show an unexpected relationship.

WOLVERINE AND SHEEP

The wolverine (Gulo hylaeus) is widely distributed in the mountains in the park. In 1940 and 1941, after a period of low numbers, is was reported to be on the increase. It was reported as abundant in 1927 and 1928, but I do not know when the numbers became reduced. Wolverine abundance may have been correlated with the high sheep population when much carrion was undoubtedly available. Several times I found the scattered remnants of a sheep carcass which had been investigated by a wolverine, but I have no authentic data on the relationship of the wolverine to the sheep. One circumstance cited as evidence that wolverines prey on sheep is that the former are commonly found on mountains near timber line where mountain sheep range. However, it should be added that wolverines occupy a similar habitat in areas where there are no sheep. The number killed by wolverines under any circumstance is undoubtedly small.

LYNX AND SHEEP

During the period of this study the lynx (Lynx canadensis canadensis) was very scarce; not a single track was noted.

In the winter of 1907—8, Sheldon (1930) found two sheep which had been killed by lynxes. One of the victims was a 2-year-old ewe and the other a ram, about 2 years old. In each case, the predator had lain in ambush, leaped from above to the sheep's back, and had bitten the sheep around the eyes.

Ordinarily the lynx feeds on snowshoe hares, but when the hares become scarce during the ebb of their cycle, the lynxes are left without this usual food supply. Under these conditions, they are forced to seek other food. The fact that hares were scarce in 1907—8 probably accounts for the lynxes hunting sheep at that time. After the hares disappear the lynxes also go into a decline, so their predation on sheep is only for a short time and probably is never a serious factor.

In 1927 there was a big die-off in the hare population. It is reported that hares were unusually abundant in the fore part of the summer but that during August they became extremely scarce. It is interesting to note that in the Superintendent's reports for 1927 and 1928 the lynx was reported increasing. Possibly due to the hare die-off, lynxes began to wander about in search of food, especially in the sheep hills, and so were noticeable. After 1928 there is no mention of lynx abundance, and they have been scarce since that time.

COYOTE AND SHEEP

The coyote, Canis latrans incolatus Hall, was so scarce in the sheep hills that there was no opportunity to study its possible effect on the mountain sheep population. I saw a coyote on three occasions at Sable Pass, and once near Teklanika Canyon. These were the only coyotes seen during the three summers and one winter which I spent in the field. In recent years they have been reported somewhat common near the northeast corner of the park where snowshoe hares have been present in moderate numbers; and in the low country north of the park a few are reported by trappers.

The coyote frequently has been listed as a destroyer of the Rocky Mountain bighorn in the States, but the few studies which have been made indicate that the coyote is not a serious enemy of these sheep. In Yellowstone National Park I found no evidence of coyote predation on the bighorn, not even in summer when lambs in some situations seemed to be vulnerable to coyote attack, and coyotes on these summer ranges were common (Murie, 1941). Other investigators in Yellowstone National Park have not found evidence that coyotes were a serious menace to the mountain sheep. In Jackson Hole, Wyo., coyotes were suspected of destroying many lambs, but investigations indicated that the lambs were dying of disease rather than coyote predation (Honess and Frost, 1942). In a study of a prospering bighorn herd in Colorado, where coyotes are common in the sheep area, known losses from coyotes were small (Spencer, 1943).

The scarcity of coyotes in the sheep hills in Mount McKinley National Park may indicate that they cannot find sufficient food there. Of course in the absence of the wolf, there would be more weak sheep and carrion available to them, and more coyotes might then occupy the sheep hills. For this food supply they probably cannot compete with the wolf, since they are a weaker predator in respect to the sheep. It is possible that the wolf tends to drive out the coyote by attacking it, although both species once occupied the same general territory in the States. I am inclined to believe that the main reason that the coyotes are not in the sheep hills is that the staple rodent supply is more abundant in the lower country. Possibly coyote distribution is much influenced by the distribution of snowshoe hares also.

In 1932, when many sheep were succumbing to the unusually severe winter conditions and others were weakened by them, it is reported that some sheep were killed by coyotes. Such predation on weakened animals is not at all unlikely, but the information at hand does not indicate any consistent or serious predation by coyotes on the mountain sheep herds of Mount McKinley National Park.

GOLDEN EAGLE AND SHEEP

Lambs Well Protected When Young.—Charles Sheldon (1930, p. 33) writes as follows concerning his observations on relationships between the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos canadensis) and white sheep: "While hunting sheep in the Yukon Territory during the two previous years, and also while in the Alaska Range that summer, I observed the relations between golden eagles and sheep, not once noticing any antagonism between them—but only complete indifference." On May 25, 1908, Sheldon saw an eagle swooping at some ewes and lambs and states that it was the first time that he had seen an eagle swoop at sheep or even notice them. The ewes stood over their lambs to protect them from the eagle. On June 7, 1908, Sheldon (1930, p. 382) reports seeing eagles swooping at lambs but states that no capture was made, and that the ewes were very watchful when the eagle was near. An eagle's nest was nearby and near it Sheldon found lamb remains. He shot the eagle on the nest and found the stomach filled with ground squirrel remains. He concluded that it was probably true that the eagles preyed heavily on young lambs but that they were seldom molested by them after they were a month old. The evidence to support his conclusions that "it is undoubtedly true that golden eagles take a heavy toll of the newly born lambs" was his observation of some eagles swooping at ewes and lambs, and the lamb remains found at the one nest. His other experiences had caused him to conclude that eagles did not molest the sheep.

Joseph S. Dixon (1938) spent the summers of 1926 and 1932 making wildlife studies in Mount McKinley National Park. In 1932 he made observations on four eagle nests but found no fresh lamb remains in or below them. However, it should be taken into account that the lamb crop that year was very poor, so fewer lambs than usual were available to the eagles. Dixon (1938, p. 46) draws the following conclusion concerning eagle-sheep relationships; "Our experience in the region both in 1926 and in 1932 indicated that during these two seasons lambs were rarely taken by eagles, which were found to live chiefly upon ground squirrels and marmots."

Former Ranger Lee Swisher stated that he had visited several eagle nests but never found any lamb remains at them.

I have observed eagles dive at ewes and lambs, but such maneuvers do not necessarily gage the degree of eagle predation on lambs. Eagles have also been observed swooping low over grizzlies and wolves at times when there was no intent of predation. Once an eagle dove at an adult wolf which was standing near its den. About a dozen times the eagle swooped, barely avoiding the wolf which each time jumped into the air and snapped at it. The eagle turned upward at the right moment to avoid the leap, and apparently was enjoying the game.

During the first few weeks the lamb remains close to its mother. It usually lies down beside her when she is resting, follows her closely, or lies down only a few feet away while she feeds. In traveling, the young lamb often presses close to its mother's side, sometimes appearing to be partially under her. The lamb is near its mother except when left with other lambs, usually on a cliff, while she goes off a short distance to feed. But at such times the group of lambs is watched over by some of the ewes. So, at the time when the lamb would be most vulnerable to eagle attack, it is generally well protected, giving to the eagle little opportunity to prey on it.

Figure 35: "Come on!" |

After a few weeks the lambs move about with more freedom and gambol over the meadows in little groups. Judging from their behavior, they are not greatly worried about eagles after 3 or 4 weeks. In late June and early July I have seen eagles fly low over lambs, separated from their mothers, without attempting to strike and without alarming them. Throughout the summer the eagle may occasionally dip downward at the sheep just as is does at other animals. On September 10 an eagle swooped low over two ewes and a lamb, giving them quite a start. It sailed close over them several times, calling as is passed. But after the first start the sheep seemed unafraid.

Few Lamb Remains Found at Nests.—Upon examining the vicinity of seven unoccupied eagle nests only one lamb bone was found. It was a skull which lay in slide rock some distance below the nest.

As the 13 occupied nests examined during the three summers, one old leg bone of a lamb was found below one nest and at another were the remains of two recently eaten lambs. The presence of two lambs at the one nest may have indicated that this particular pair of eagles was more inclined to attack lambs than were other eagles, or else were more fortunate in finding unprotected lambs, or possibly dead ones. One eagle was seen feeding upon a lamb which appeared to be about a week mild. As 11 of the 13 nests occupied no lamb remains, old or recent were found.

It should be pointed out that in some cases the eagle eggs do not hatch until the lambs are 3 or 4 weeks old and probably past the danger period. In these instances possibly lambs would not be taken to the nest. However, they might be brought to favorite perches near the nest where some of them would have been found if any significant number had been consumed.

During the period that the eagles are at the nest the parent birds bring to it twigs of birch, heather, or willow, probably to cover debris accumulating in it. In one nest an eagle had brought several mats of shed sheep hair, the presence of which could easily have been misconstrued as evidence of predation.

Eagle Pellets Contain Few Lamb Remains.—During each of the three summers spent on the study, substantial numbers of eagle pellets were collected from perches and nests in the lambing area. The pellets give a fairly good index of the food habits of the eagle during these 3 years. Of 632 pellets analyzed, only 6 (2 each year) contained remains of lambs. This low incidence of lamb in the eagle pellets strongly corroborates the evidence from nest examinations and general observations. The considerable information available supports the conclusion that only occasionally does an eagle feed upon a lamb. Such lambs may have been carrion or may have been killed by the eagles. If killed, they may have been healthy, weak, or deserted. In any event, whatever eagle predation exists, it is apparent that it would have no appreciable effect on the mountain sheep population.