|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

An Identification of Prairie in National Park Units in the Great Plains NPS Occasional Paper No. 7 |

|

SECTION TWO:

IDENTIFICATION OF PRAIRIE IN NATIONAL PARK UNITS

MIDWEST REGION

AGATE FOSSIL BEDS

National Monument

Nebraska

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument contains concentrations of animal fossils in beds of sedimentary rock, formed about 20 million years ago by the compression of mud, clay, and erosional materials. The beds, which acquired their name from their proximity to rock formations containing agates, are under prairie-covered hills. From the summits of Carnegie and University Hills, named by early collecting parties, one can look 200 feet (73 meters) down across grass-covered slopes to the narrow Niobrara River. The Niobrara Valley and surrounding prairie are also rich with American Indian and ranching history. The establishment of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument was authorized on June 5, 1965.

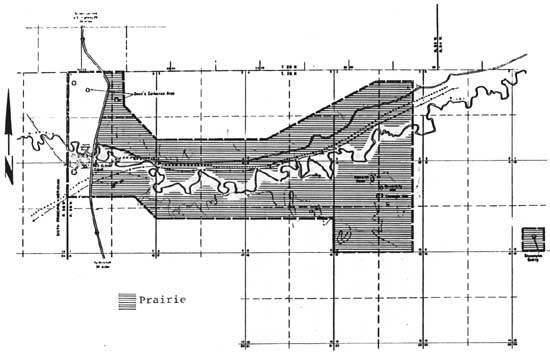

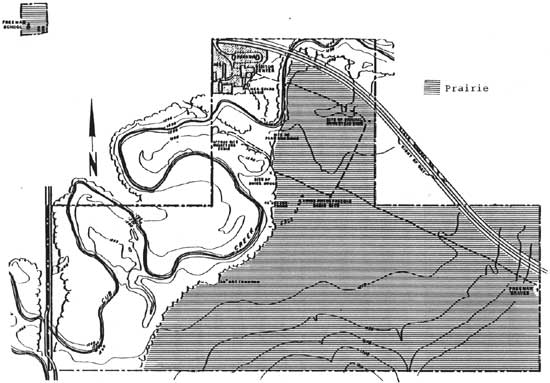

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument contains 3,055 acres (1,237 hectares), including the detached Stenomylus Quarry. Federal land totals 2,737.5 acres (1,108.3 hectares), and there are 317.7 acres (128.6 hectares) of nonfederal land. About 450 acres (182 hectares) is restricted to livestock use under scenic easement. A narrow corridor, estimated to contain no more than 300 acres (121 hectares) of floodplain with a marsh type of vegetation, occurs adjacent to the Niobrara River. Therefore, approximately 2,755 acres (1,115 hectares) are classified as prairie (Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3. Prairie map, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: Grama—Needlegrass—Wheatgrass (Bouteloua—Stipa—Agropyron) (Map No. 64)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

Fire and grazing played important roles in the development of the prairie in this region. The area was moderately to heavily grazed by domestic livestock, primarily before the establishment of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. The area has not been grazed since the mid-1960's, although the 450 acre (182 hectare) area under scenic easement is subject to livestock use.

Current vegetation is in excellent condition and is, therefore, similar to the historic climax plant communities. Primary species include needleandthread, blue grama, western wheatgrass, slender wheatgrass, prairie sandreed (Calamovilfa longifolia), indian ricegrass, rush skeletonplant (Lygodesmia juncea), fringed sagewort, and little bluestem. Sand dropseed, downy brome (Bromus tectorum), sunflowers (Helianthus spp.), sweet clovers (Melilotus spp.), and Rocky Mountain beeplant (Cleome serrulata) may be found on disturbed sites. Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) and wild currants (Ribes spp.) are common shrubs.

A portion of the upper floodplain shows evidence of cultivation. Scattered plants of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) are common. Other weedy species on formerly cultivated areas include Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), flodman thistle (Cirsium flodmani), and quackgrass (Agropyron repens).

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

The area surrounding Agate Fossil Beds National Monument is classified as agricultural. Nearly all of the area is grazed by domestic livestock. Vegetation on the surrounding land is similar to that present within the boundary of the park.

Prairie Research

Dr. Ronald R. Weedon, Chadron State College, initiated a study of the vegetation of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument in 1983. A collection of vascular plants is being assembled, vegetation is being quantitatively sampled, and fixed point photographs are being made to document visual changes in the prairie.

Landers, Roger Q. 1975. A report on the status and management of native prairie areas in the National Parks and Monuments in the Midwest Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

Dr. Landers described the prairie vegetation of Agate Fossil Beds and made management recommendations. He indicated that most the prairie was in excellent condition. The exceptions were weedy areas near the former Hoffman Ranch and some of the upper floodplain areas.

General References

National Park Service. 1966. Master plan. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument/Nebraska. 33 pages.

National Park Service. 1976. Statement for management. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument/Nebraska. 12 pages.

National Park Service. 1978. Interpretive prospectus. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument/Nebraska. 21 pages.

CHIMNEY ROCK

National Historic Site

Nebraska

Chimney Rock was an important visual landmark for the mountain men on their seasonal travels in the early 1800's. It was named for its chimney-like shape in 1827. Its name and descriptions are found in the journals of hundreds of emigrants who crossed the plains in covered wagons. Its spire and solitary grandeur drew many travelers from the Oregon Trail who climbed to the tower and carved their names in the clay. The establishment of Chimney Rock National Historic Site was authorized on August 9, 1956. The State of Nebraska owns the site. It is jointly administered by the city of Bayard, the Nebraska State Historical Society, and the National Park Service. The National Park Service provides interpretive advice and professional assistance when requested. It does not manage the land resource.

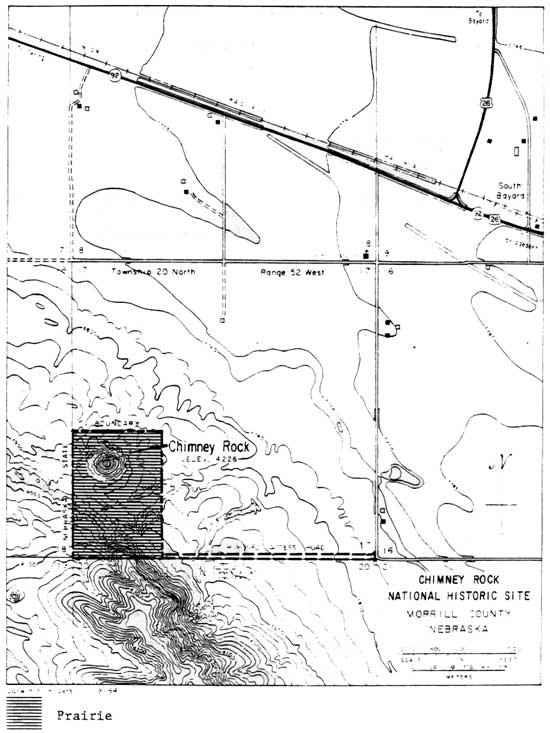

The site is made up of 83.8 acres (34 hectares). Approximately 65 acres (26 hectares) are prairie, and the remaining 18 acres (7 hectares) are classified as badlands with little vegetation (Figure 4).

|

| Figure 4. Prairie map, Chimney Rock National Historic Site. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: Grama—Buffalo Grass (Bouteloua—Buchloe) (Map No. 65)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

The prairie on this site has never been plowed. Historically, it was heavily grazed by domestic livestock in a typical ranching program. Heavy grazing reduced or removed many of the taller species of plants, leaving a rather dense sod of short grasses. There has been no grazing in recent years. The primary grasses are blue grama and buffalograss. Other species include western wheatgrass, western ragweed (Ambrosia psilostachya), red threeawn, cudweed sagewort (Artemisia ludoviciana), sand sagebrush (Artemisia filifolia), annual erigonum (Erigonum annum), scarlet gaura, senecios, sand dropseed, needleandthread (Stipa comata), and small soapweed. Protection from grazing is allowing some of the taller species to increase.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

All of the land surrounding Chimney Rock National Historic Site is classified as agricultural. The majority of the surrounding area remains in rangeland and is grazed by domestic livestock, primarily cattle. Some of the land is farmed. Prairie vegetation on grazed lands is similar to that within the boundaries of the park, but it is generally not in as good of condition.

Prairie Research

No prairie research studies have been conducted at this location.

General References

National Park Service. 1964. Chimney Rock National Historic Site/Nebraska. Brochure. 2 pages.

EFFIGY MOUNDS

National Monument

Iowa

Effigy Mounds National Monument was established to preserve Indian burial mounds in northeastern Iowa. Within the boundaries are 191 known prehistoric mounds. Twenty-nine are in the form of bear and bird effigies, and the remainder are conical or linear shaped. Effigy Mounds National Monument was established on August 10, 1949. Additional lands were added in 1951 and 1961 making a total of 1,474.6 acres (597 hectares) which is divided into three units. The main area is divided into the North Unit and the South Unit. About 120 acres (49 hectares) of the total is in the Sny Magill Unit which is located 11 miles (18 kilometers) south of the main units.

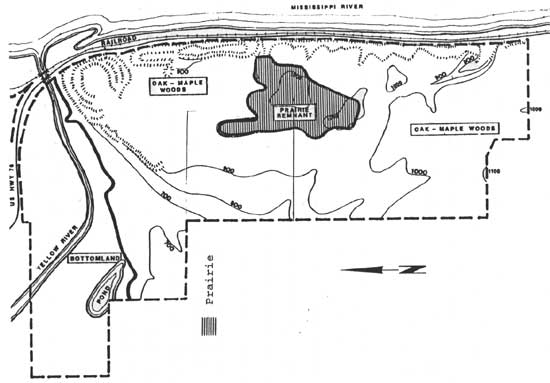

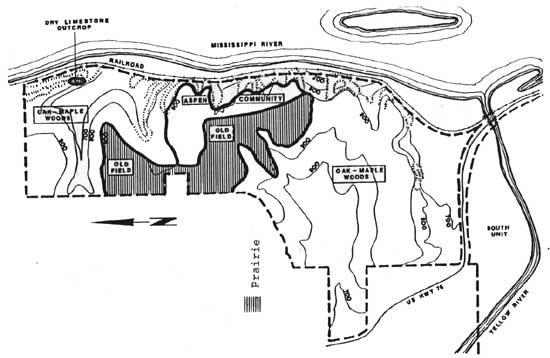

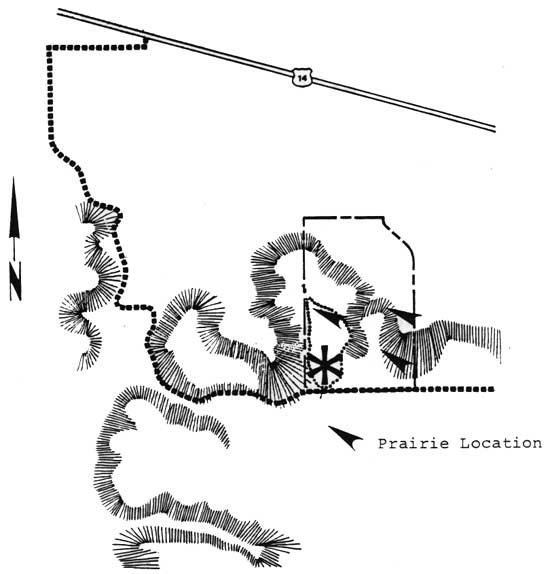

A prairie remnant of approximately 29 acres (12 hectares) is present in the South Unit (Figure 5). A small limestone outcrop and larger areas of old fields are present in the North Unit (Figure 6). The North Unit contains about 41 acres (17 hectares) within this category.

|

| Figure 5. Prairie map, Effigy Mounds National Monument (South Unit). |

|

| Figure 6. Prairie map, Effigy Mounds National Monument (North Unit). |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: A mosaic of Bluestem prairie (Andropogon—Panicum—Sorghastrum), Oak—Hickory Forest (Quercus—Carya), and Maple—Basswood Forest (Acer—Tillia) (Map Nos. 74, 99, and 100)

The prairie remnant at Effigy Mounds National Monument would fit under the Bluestem Prairie vegetation type. Oak—Hickory Forest (Quercus—Carya) and Maple—Basswood Forest (Acer—Tillia) are common in the area.

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

The area was probably lumbered two or three times in the historic period. The oldest trees in the monument are only 60 to 70 years old. Level upland sites were cleared for farming. A complete removal of the forest for lumber occurred near the turn of this century. These areas are rapidly returning to trees, and much of the area has returned to dense forest cover. Historically, fires seldom occurred with enough force to damage the forest. However, fires commonly swept up the prairie openings and consumed trees on the ridges. Fire scars are evident on many of the old trees in the park, especially those adjacent to the prairie remnants and limestone outcroppings.

The level uplands in both the North and South Units were farmed until the 1940's and then allowed to revegetate naturally. Portions were grazed and mowed, but no attempt is currently being made to keep these areas open.

Vegetation of the prairie remnant is currently composed of approximately 40 species. Common species are New England aster (Aster novae-angliae), smooth bromegrass (Bromus inermis), staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina), and indiangrass. Prairie species intermediate in abundance include blue aster and goldenrods. Species rare at the site include big bluestem, little bluestem, heath aster, tick trefoil (Desmodium illinoense), Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis), soapwort gentian (Gentiana saponaria), rough gayfeather, grayhead prairie coneflower, and prairie dropseed. Trees intermediate in abundance on the prairie are eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), and black cherry (Prunus serotina). These groups of species and their relative abundances indicate that the prairie is not in good condition.

Species lists from the limestone outcrop at the North Unit show numerous prairie species including leadplant, big bluestem, little bluestem, hairy grama, Canada wildrye, and prairie dropseed. Species present on the old field on the North Unit include some prairie species. Introduced species are more common on the site, indicating that succession is not approaching a prairie climax.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

Land use surrounding Effigy Mounds National Monument is primarily forest and pasture, with some agricultural production consisting mainly of corn. The Mississippi River is adjacent to the eastern boundary of the monument.

Prairie Research

Landers, Roger Q. 1975. A report on the status and management of native prairie areas in National Parks and Monuments in the Midwest Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 126 pages.

Dr. Landers reported bluestem prairie on extreme south facing slopes and rocky bluffs. The open prairie areas were reported to be rapidly returning to forests. The prairie areas contained many characteristic grasses and forbs.

Howell, Evelyn, Darrel Morrison, and Gregg Moore. 1983. Vegetation survey of Effigy Mounds National Monument. Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin. 126 pages.

The following plant communities have been identified: Prairie Remnant, Old Field, Oak—Maple Woods, Bottomland, and Aspen. These researchers have also assembled species abundance lists for each plant community.

Blewett, Thomas J. 1985. A vegetation survey of grasslands and rare plants of Effigy Mounds National Monument. Progress report. Biology Department, Clarke College, Dubuque, Iowa.

Field surveys have located 6 state-listed rare species and 22 small prairie remnants.

General References

National Park Service. 1973. Effigy Mounds National Monument/Iowa. Brochure. 2 pages.

National Park Service. 1977. Statement for management. Effigy Mounds National Monument/Iowa. 14 pages.

FORT LARNED

National Historic Site

Kansas

In the early 1860's, Fort Larned was the northern anchor of the line of forts that outlined the military frontier of the southwestern portion of the United states. Fort Larned was first charged with protecting the mail and travelers on the eastern segment of the Santa Fe Trail. Later it served as a base for military operations against the hostile Indians of the central Great Plains. By 1878 the fort was abandoned, and in 1884 the buildings and land were sold at public auction. It remained in private ownership until the establishment of Fort Larned National Historic Site was authorized on August 31, 1964.

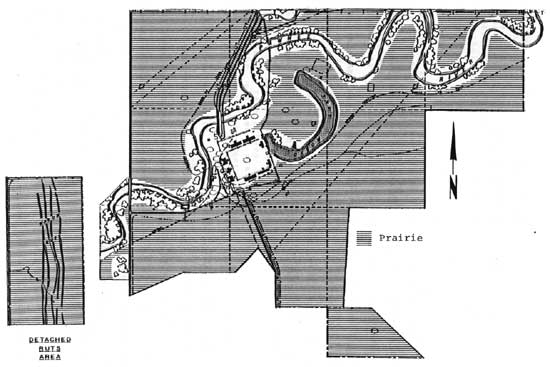

The Fort Larned National Historic Site contains 718.4 acres (290.8 hectares) in two separate tracts (Figure 7). Much of the land is in scenic easement. The detached Santa Fe Trail Ruts tract of 44 acres (18 hectares) is located 5 miles (8 kilometers) southwest of Fort Larned. The Santa Fe Ruts tract is native prairie. Approximately 82 acres (33 hectares) of the main unit is classified as riparian. About 277 acres (121 hectares) have been reseeded to native prairie species and are in various stages of succession.

|

| Figure 7. Prairie map, Fort Larned National Historic Site. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: Bluestem—Grama Prairie (Andropogon—Bouteloua) (Map No. 69)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

The Fort Larned National Historic Site has been divided into 12 vegetation management units. It can be postulated that all of the site was grazed while Fort Larned was active. In all probability, areas close to the stables and pens received heavy grazing. Following abandonment and sale of the property, most of the land was farmed. Small fragments of the original prairie sod exist along the banks of the Pawnee River. A small area of native sod is also present near the former military dump in Unit 3.

The detached Santa Fe Trail Ruts Tract, Unit 12, is original prairie sod. Intensive grazing by domestic animals has removed most of the tall and mid-grasses. Grazing by domestic animals has been eliminated, but the plants on much of the area have been grazed or clipped near the soil surface by prairie dogs. Prairie dog control measures have recently been initiated.

In 1968, a project was initiated to convert the cultivated land back into native vegetation as a part of recreating the historic scene. Although the area had originally supported a mixture of tall, and mid-, and short grasses, blue grama and buffalograss were the primary species selected for planting. The reason for this decision to use short grasses was the concern that taller grasses would constitute a fire hazard.

The original plan was to progressively seed portions of the area to grass during a five-year period. Two planting methods were employed: (1) planting native grasses directly into a prepared seedbed and (2) planting sudangrass (Sorghum vulgare) in the spring and harvesting in the fall, leaving a four-inch (ten-centimeter) stubble in which to seed the native grasses the following spring. All of the seedings were not completed during the proposed five-year period. Most of the vegetation management units were mowed for weed control through 1979. Herbicides were also occasionally used for weed control. Prescribed burning was initiated as a management tool in 1983 and mowing intensity has generally decreased.

At present cool season, weedy grasses dominate several of the units and weedy forbs are a problem in several areas. Noxious grasses and forbs are also present. Native short grass cover has appeared to be static for at least the last 5 years but mid-grass cover has increased slightly. Tall grass cover is sparse in most areas, but levels are increasing in several plots. Levels of both mid- and tall warm season grasses must increase several-fold before a desired climax prairie is reached. A summary of each unit follows:

Vegetation Management Unit 1. An excellent plant cover exists in this unit. It furnishes the historic site with an example of a western Kansas short grass prairie. The western 4.5 acres (1.8 hectares) were seeded to a slightly different mixture than the remaining area. Silver bluestem (Bothriochloa saccharoides), representative of southwestern prairies, may be found in this area. Blue grama and buffalograss account for the majority of the cover. Other important species are sideoats grama and little bluestem. Weedy species such as dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) and tall lettuce (Latuca canadensis) are present. Hay was cut from the area in July 1981. A prescribed burn was conducted on this unit during the third week in April 1982.

Vegetation Management Unit 2. Species present in this unit are similar to those in Unit 1. Buffalograss and blue grama represent nearly half of the cover. Colonies of bur ragweed (Ambrosia grayi) remain from the period of cultivation. Forage and litter were removed by haying in April and July 1981 and July 1982. This unit was burned in 1985.

Vegetation Management Unit 3. Vegetation Management Unit 3 is composed of three distinct types of vegetation. Over one-forth of the cover is western wheatgrass. This species occurs primarily on the slopes. Buffalograss was planted in 1980 on the disturbed sites, and a small amount of native sod exists on the top of a small hill along the south border of the Fort Larned National Historic Site. A prescribed burn was conducted in this unit in 1985.

Vegetation Management Unit 4. Unit 4 has an excellent cover of tall, mid-, and short grasses. Over 50% of the area is occupied with buffalograss and blue grama. Switchgrass, sideoats grama, silver bluestem, and sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus) are also common. Litter and forage were removed from this area by cutting and baling in April and July 1981 and July 1982. This unit was burned in 1984 and 1985.

Vegetation Management Units 5, 6 and 7. These Vegetation Management Units have similar vegetation. Vegetation was characterized in 1980 by large quantities of undesirable plants such as downy brome (Bromus tectorum) and kochia (Kochia scoparia). The highly fertile soils adjacent to the Pawnee River originally would have supported tall grasses such as big bluestem, switchgrass, and indiangrass. The seeded short grasses are unable to compete with the weedy species on this site. The east portion of Unit 5 and all of Units 6 and 7 were mowed and baled in April and July 1981 and July 1982. The west portion of Unit 5 was mowed with a flail mower in 1981 and 1982. Portions of Units 5, 6, and 7 were burned in the period 1983-85. A 4 acre (1.6 hectare) area in the western part of Unit 5 was mowed, lightly disked, and planted to a mixture of prairie grasses and forbs in 1983.

Vegetation Management Unit 8. A large portion of Unit 8 has unsatisfactory vegetation which is similar in composition to that in Units 5, 6, and 7. Vegetation on this unit was cut and baled in April and July 1981. The area was burned during the third week of April 1982.

Vegetation Management Units 9 and 10. Units 9 and 10 are the two smallest units. Botanical composition data collected in 1980 indicate an abundance of weeds and few prairie species. These units were mowed with a flail mower in 1981. They were burned in April 1982.

Vegetation Management Unit 11. Vegetation Management Unit 11 is located in and around the building site. It has generally been closely mowed throughout the growing season. The resultant vegetation is primarily buffalograss with a few common lawn weeds.

Vegetation Management Unit 12. The detached Santa Fe Trail Ruts tract, or Vegetation Management Unit 12, has the greatest diversity of species on the Fort Larned National Historic Site. Many years of intensive grazing by domestic animals eliminated or greatly reduced many of the tall and midgrass species. The shortgrass sod is dominated by buffalograss, but numerous undesirable weedy species are present. The prairie dog population in this Unit was substantially reduced following control measures initiated in January and December of 1982. The unit was prescribed burned in 1984.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

The area surrounding the Fort Larned National Historic Site is almost exclusively classified as agricultural. Most of the land is used for the production of wheat (Triticum aestivum), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), and grain sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). Vegetation in the riparian area outside of the park boundary is similar to that within the boundary.

Prairie Research

Landers, Roger Q. 1975. A report on the status and management of native prairie areas in National Parks and Monuments in the Midwest Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 126 pages.

Dr. Landers described the vegetation of 22 plots at Fort Larned National Historic Site. Some of these plots have now been combined to form the 12 Vegetation Management Units. Specific management recommendations were made concerning mowing, seeding, and burning.

Stubbendieck, J., Catherine Jo Wiederspan, and Kathie J. Kjar. 1980. Prairie restoration: an evaluation and specific recommendations for management. Natural Resources Enterprises. Lincoln, Nebraska. 95 pages.

Physical conditions, including climate and soils, of the area were described. The original vegetation of the bluestem prairie, floodplain forest, and freshwater marsh is characterized. The 12 vegetation management units of the historic site were delineated, and the management history of each was presented. The 1980 vegetation of each unit was described in terms of basal cover of individual species. A five-year management program, by units, was recommended. A second part of this research involved assembling an herbarium collection. More than 200 species were collected. This report listed the specimens by scientific name (including authority), common name, and lists the vegetation management units in which they occur. Instructions for specimen preparation and herbarium maintenance are also included.

Becker, Donald A. 1985. Vegetation survey and prairie management plan for Fort Larned National Historic Site. Ecosystems Management. Elkhorn, Nebraska. 90 pages.

Dr. Becker placed transect lines across the vegetation management units and established permanent quadrats along these lines. He recorded density, frequency and cover data. Additional herbarium specimens were collected. He developed a prairie management plan which included options and opportunities for recreating the historic vegetation scene.

General References

National Park Service. 1978. Fort Larned. Fort Larned National Historic Site/Kansas. A brochure. 2 pages.

National Park Service. 1978. Master plan. Fort Larned National Historic Site/Kansas. 43 pages.

National Park Service. 1978. Statement for management. Fort Larned National Historic Site/Kansas. 30 pages.

FORT SCOTT

National Historic Site

Kansas

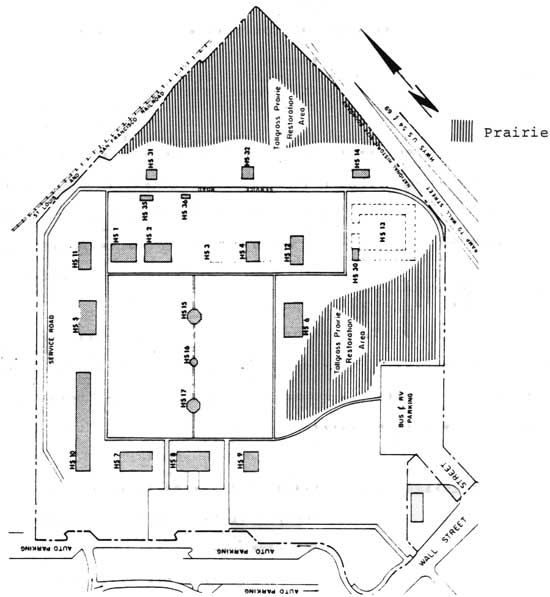

Fort Scott was established in 1842 as a base for U.S. Army peace-keeping efforts on the Indian frontier. It was abandoned in 1853 and became a civilian community. It was reactivated during the Civil War and also for a short period in the 1870's. The establishment of Fort Scott National Historic Site was authorized on October 19, 1978. Fort Scott National Historic Site is located within Fort Scott, Kansas. Federal land totals 16.8 acres (6.8 hectares). It contains about 4 acres (1.6 hectares) of restored tallgrass or bluestem prairie.

Kuchler Vegetation Type: Mosaic of Bluestem Prairie (Andropogon—Panicum—Sorghastrum) and Oak—Hickory Forest (Quercus—Carya) (Map Nos. 74 and 100)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

Prairie was eliminated from the immediate area as the fort was being developed and occupied. A prairie restoration project began in 1979 with the planting of a mixture of forbs and grasses. The grass mixture was big bluestem (16%), little bluestem (50%), sideoats grama (12%), switchgrass (8%), and indiangrass (14%). The forb mixture was leadplant (10%), Maxmillian sunflower (Helianthus maximiliana) (5%), tall gayfeather (Liatris scariosa) (11%), purple prairie clover (Petalostemum purpureum) (14%), grayhead prairieconeflower (30%), blackeyed susan (Rudbeckia hirta) (10%), pitcher's sage (Salvia pitcheri) (10%), and compassplant (10%). The two mixtures were combined before seeding. The restored prairie areas have been maintained by mowing. Sideoats grama, indiangrass, and little bluestem are well established in the area behind the carriage house and post bakery. Grayhead prairieconeflower, Maxmillia sunflower, indiangrass, sideoats grama, and big bluestem were noted in the area near the infantry barracks in 1983.

|

| Figure 8. Prairie map, Fort Scott National Historic Site. |

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

Historic Fort Scott sits on a low limestone bluff overlooking the Marmaton River. It is located totally within the city of Fort Scott. The principal fort area is level but the east side of the park slopes gently downhill. The surrounding terrain is relatively flat and is occupied with commercial and residential buildings. A portion of the area is still classified as agricultural with cultivated farmland.

Prairie Research

Dr. Jim Jackson, Missouri Southern State College is currently comparing the fort's restored prairie with a nearby native prairie. He will develop guidelines for future restoration.

General References

National Park Service. 1967. A master plan. Fort Scott Historical Park/Kansas. 71 pages.

National Park Service. 1981. Interpretive prospectus. Fort Scott National Historic Site/Kansas. 39 pages.

National Park Service. 1981. Statement for management. Fort Scott National Historic Site/Kansas. 14 pages.

National Park Service. 1982. Fort Scott National Historic Site/Kansas. A brochure. 4 pages.

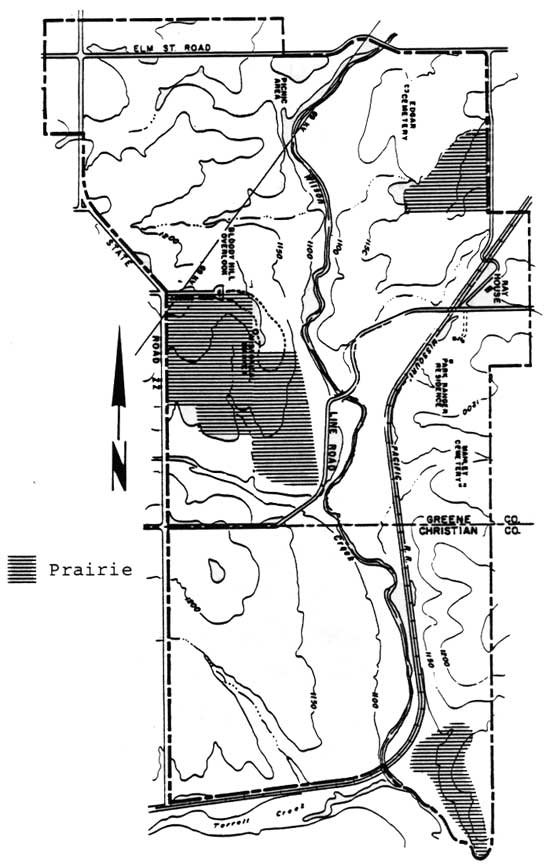

GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER

National Monument

Missouri

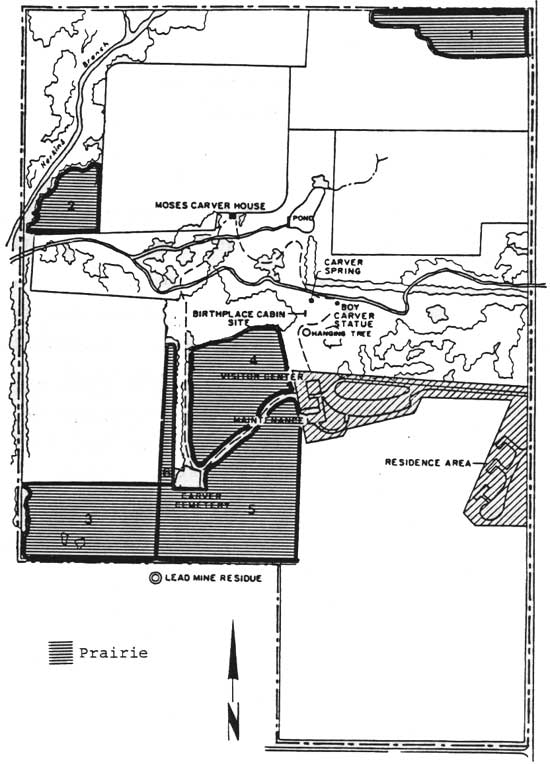

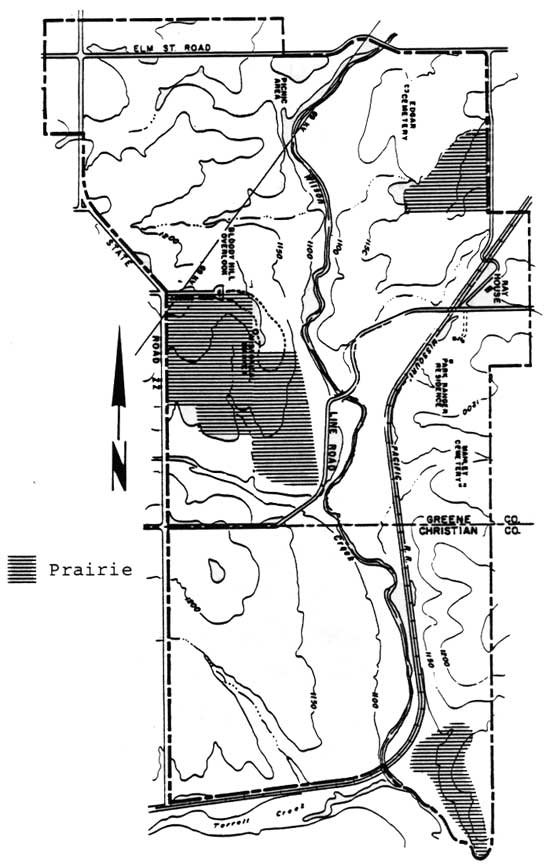

George Washington Carver National Monument was authorized in 1943 and formally established in 1953 as a memorial to the accomplished scientist. He grew up on the Moses Carver farm during the 1860's and 1870's. Most of the farm is located within the current park's boundaries. The park contains 210 acres (85 hectares). Five prairie areas are located within its boundaries. Seeded and natural prairie occupies approximately 55 acres (22 hectares) (Figure 9).

|

| Figure 9. Prairie map, George Washington Carver National Monument. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: A mosaic of Bluestem Prairie and Oak—Hickory Forest (Andropogon—Panicum—Sorghastrum) (Quercus—Carya) (Map Nos. 74 and 100)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

Much of the land at George Washington Carver National Monument is relatively level and fertile and was once cultivated or used as pasture. Jackson and Bensing (1982) described five prairie areas totaling approximately 25.2 acres (10.2 hectares). They were characterized on the basis of interviews, historical documents, aerial and ground photographs, vegetational plot sampling, compilation of a species list, soil classification and soil analysis. All five areas were originally native prairie at the time of Moses Carver's occupancy of the farm.

The primary park objective is to recreate the historic scene of the 1860's Moses Carver farm through the restoration and reestablishment of these native prairie areas.

Five management units have been established. All five units were burned in March 1982 and overseeded with a mixture of native grasses. Management Unit 6 was included within the restoration program in 1982.

Management Unit 1 (3.8 acres or 1.5 hectares) shows no evidence of tillage. It is in an early stage of natural prairie succession. The western one-third has been protected from grazing and fire, which has resulted in a dense, unnatural stand of woody plants. The eastern portion has been historically mowed in the spring and again in the late summer or early fall. Some light grazing has also occurred. In 1981, big bluestem and broomsedge (Andropogon virginicus) were the two most important species in this unit. Tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) is an undesirable cool season invader, and it was fourth most important in Management Unit 1. This unit was burned on March 24, 1982, and was overseeded with a mixture of native grasses and forbs. Subsequent evaluation in July and September of 1982 indicated big bluestem and little bluestem have increased significantly. This unit was burned in April of 1983 and limited areas were seeded in May.

Management Unit 2 (2.8 acres or 1.1 hectares) shows evidence of tillage. Historical records indicate that it has been subjected to many years of severe overgrazing. Invading woody plants were removed in the spring of 1982. Species composition data in 1981 showed that it was dominated by weedy species. It was tilled and seeded to prairie species in 1982. Evaluation of this seeding in July and September of 1982 indicated little bluestem seedlings ranked fourth in importance. This species was not present in the 1981 sampling. Poor growth resulted from undesirable weather conditions, and the area was reseeded in May 1983.

The eastern portion of Management Unit 3 was subjected to intensive tillage for many years before it was designated as a pasture. Total area of the unit is 4.3 acres (1.8 hectares). Broomsedge and tall fescue were the dominant species. The western portion has been protected from grazing and fire, which has resulted in a dense stand of woody plants. In 1982, a portion of the area was burned, and the rest was tilled. It was seeded to forbs and grasses in May 1982. Evaluation of the western portion in July and September of 1982 indicated that while woody species still dominate, little bluestem now ranks fourth in importance. Mowing has been used as a management tool because sufficient ground cover is not present for burning. A restoration program, which includes disking and reseeding, for the lower eastern portion was initiated in 1984.

Management Unit 4 (4.6 acres or 1.9 hectares) has had a diverse history. At various times it has been a barnyard, plowed field, and a site for a roadway. Several other uses have been made of the land. The dominant species was Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), which is an undesirable cool season invader. Various other species were also present. This unit was burned, disked, and seeded in the spring of 1982. The restoration success has been severely impeded by poor climatic conditions and competition from cool season exotic species. The eastern one-half of this unit was reseeded in May of 1983 and still represents a major management concern.

Management Unit 5 (9.7 acres or 3.9 hectares) contains several pure stands of big bluestem, little bluestem, and indiangrass. Annual mowing was the management practice for many years, but recently it was done on a three-year interval. This unit were burned, shallowly disked, and seeded to prairie species in 1982. In vegetative studies completed in September 1982, big bluestem was ranked first in importance. This unit was burned again in April of 1983, and selected areas were subjected to reseeding.

Management Unit 6 (1.5 acres or 0.6 hectares) was included within the restoration program in 1982. It was burned, disked, and seeded. Analysis of this unit in 1982 indicated that big bluestem and little bluestem were present in high frequencies.

Followup studies were conducted on these management units between 1982 and 1985. All units except four showed an increase in native prairie species and a decrease in noxious weedy plants. In unit 4 the vegetational composition improved but not as dramatically as in the other units.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

Land use within one mile (1.6 kilometer) of the park is basically agricultural. A few cereal and row crops are produced and grazing occurs. Grazing is done on pastures seeded to tall fescue. Approximately 360 acres (146 hectares) of native prairie remain in the area. Woody plants commonly occur on lowlands and waste areas. To the southwest of the park, a small tailing pile remains from a previous mining operation.

Prairie Research

Landers, Roger Q. 1975. A report on the status and management of native prairie areas in National Parks and Monuments in the Midwest Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 126 pages.

Comments on George Washington Carver National Monument within this report are limited to the 19-acre (8 hectare) pasture west of the visitor center. It is not known if it was ever cultivated. The pasture was mowed twice yearly from 1952 through 1973. It was mowed once in 1974 and in 1975. Dr. Landers indicated that this area was in excellent condition. He recommended continued mowing and did not recommend a prescribed burning program.

Jackson, James R. and Betty Bensing. 1982. A historic and vegetational survey of the five prairie areas at George Washington Carver National Monument. Unpublished.

This vegetation survey of the prairie areas of George Washington Carver National Monument was conducted in 1981. Relative frequency, relative density, relative cover, and importance values are given for individual species. Some of these data may be found in a later published report (Groves, et al. 1983).

Jackson, James R. and Betty Bensing. 1983. A management plan for the five prairie areas at George Washington Carver National Monument. George Washington Carver National Monument Research Bulletin. 1:1-15.

The five prairie management areas at George Washington Carver National Monument were assigned specific management practices based upon the history and present vegetational composition of each unit. Management tools such as reseeding, plowing, mowing, and prescribed burning were recommended.

Palmer, Ernest J. 1983. The flora and natural history of George Washington Carver National Monument. Research/Resources Report MWR—3. Midwest Region. National Park Service. 39 pages.

This manuscript was completed in 1960. Plant updated for this publication. It includes a brief narrative history of George Washington Carver and of the George Washington Carver National Monument. A list of the vascular flora is included and is arranged by family. Common and scientific names are given.

Stockham, Jim C. and Mark M. Mense. 1983. Woody plant communities of George Washington Carver National Monument. George Washington Carver National Monument Research Bulletin. 1:16-23.

This study indicated that the woodland area of George Washington Carver National Monument is a monocommunity area. This is based on diversity and frequency data from plot samples, elevation studies, and soil analyses. Due to severe disturbance it is possible, however, that there could have originally been more than one type of woodland community.

Houlhan, Theresa M. 1983. A small mammal survey on prairie management area four at George Washington Carver National Monument. George Washington Carver National Monument Research Bulletin. 1:47-64.

A small mammal study was initiated on prairie management unit number four at George Washington Carver National Monument during the fall of 1981. This was a pre-management mammal study. The four species of small mammals that were live trapped were the cotton rat, white-footed mouse, deer mouse, and least shrew. Home range and density values were also determined.

Stejskal, James and Tony Moehr. 1983. Biomass Survey of the six prairie management units of George Washington Carver National Monument. George Washington Carver National Monument Research Bulletin. 1:65-80

A biomass survey was initiated in 1982. Past management of the prairie units is discussed. Biomass of grasses and forbs is related to the proportion of each in the seeding mixture. Biomass of the grasses varied from a low of 7.76 to a high of 34.00 grams/0.125 m2. Forb biomass varied from 1.77 to 30.85 grams/0.125 m2.

Castillon, Kim. 1983. A small mammal survey on prairie management area four at George Washington Carver National Monument. George Washington Carver National Monument Research Bulletin. 1:81-95.

A small mammal survey was conducted on an area that was subjected to burning, disking, and reseeding in the spring of 1982. The work was done in the fall of 1982 to evaluate the effects of these management tools on these rodents. Cotton rat and house mouse were the only species encountered in this study. Due primarily to the design of the study, few conclusions could be made. Home range and population density were also recorded.

Groves, Marylin, James R. Jackson, and Betty Bensing. 1983. George Washington Carver National Monument Prairie Management and monitoring program. Phase I report. Vegetational analysis and management recommendations. George Washington Carver National Monument Research Bulletin. 1:127-148.

The five prairie management areas at George Washington Carver National Monument were evaluated on the basis of their vegetational response to the prairie management program implemented in 1982 by park officials. It was found that the importance of native species such as big bluestem and little bluestem increased during this period. Specific management problems were identified such as cool season grasses and the encroachment of woody species. Future management suggestions included burning, mowing, and limited herbicide use.

General References

National Park Service. 1977. Statement for management. George Washington Carver National Monument/Missouri. 9 pages.

National Park Service. 1979. Interpretive prospectus. George Washington Carver National Monument/Missouri. 32 pages.

National Park Service. 1982. Fire management plan. George Washington Carver National Monument/Missouri. 83 pages.

National Park Service. 1982. Resources management plan. George Washington Carver National Monument/Missouri. 103 pages.

National Park Service. 1983. Prairie restoration action plan. George Washington Carver National Monument/Missouri. 59 pages.

HERBERT HOOVER

National Historic Site

Iowa

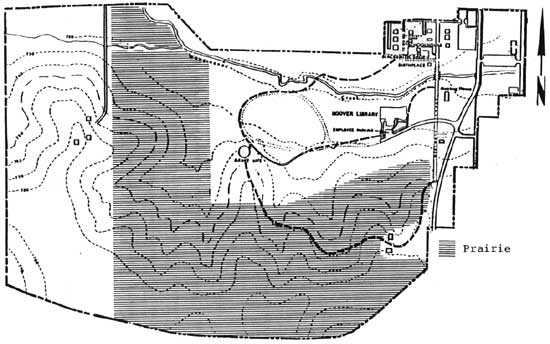

The birthplace of Herbert Hoover was designated as a National Historic Site on August 12, 1965. It is situated within the incorporated limits of the community of West Branch, Iowa. The park contains 191.1 acres (73.32 hectares) of federal land and 5.7 acres (2.3 hectares) of nonfederal land for a total of 186.8 acres (75.6 hectares). The park is rectangular in shape and is cut diagonally by the West Branch of Wapsinsonoc Creek. In the spring of 1971, 76 acres (31 hectares) of cultivated land lying to the south and west of the presidential gravesite were seeded back to native prairie grasses (Figure 10). The restored prairie was established both as a maintenance feature and as a representation of the environment characteristic of the landscape during the boyhood days of Herbert Hoover.

|

| Figure 10. Prairie map, Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: A mosaic of Bluestem Prairie (Andropogon—Panicum—Sorghastrum) and Oak—Hickory Forest (Quercus—Carya) (Map Nos. 74 and 100)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

A mixture of big bluestem, little bluestem, switchgrass, indiangrass, and sideoats grama was seeded on 65 acres (26 hectares) of upland in the spring of 1971. At the same time, big bluestem, switchgrass, and indiangrass were seeded on 11 acres (5 hectares) of wetter sites. No prairie forbs were included in the seeding mixture. Extensive annual weed growth occurred during the first growing season. The entire area was mowed in midsummer of 1971. It was burned in the spring of 1972 to stimulate the newly planted grasses and to reduce competition from weeds. Starting in 1977, 20 acres (8 hectares) were mowed each fall on a rotational basis. The hay was baled and hauled away to remove the excess organic matter which would be removed by fire in the natural ecosystem. Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) infests portions of the area. Attempted control measures have included both mechanical removal and application of herbicides.

Mowing as a general management practice was stopped in 1980. In April 1984 approximately 40 acres were burned. Following the burn, 30 acres infested with Canada thistle were chemically treated, plowed, and reseeded to a mixture of prairie grasses and forbs.

Big bluestem, indiangrass, and switchgrass dominate the prairie, comprising nearly 70% of the relative cover. Small amounts of little bluestem, sideoats grama, and Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis) are also present. Numerous forbs have moved into the area. They include Canada goldenrod, asters, giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida), common ragweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia), lettuces (Lactuca spp.), dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), American burnweed (Erechtites hieracifolia), Platte groundsel (Senecio plattensis), alsike clover (Trifolium hybridum), white sweetclover (Melilotus alba), common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), horsetail (Equisetum arvense), Pennsylvania smartweed (Polygonum pensylvanicum), hedge bindweed (Convolvulus sepium), field thistle (Cirsium discolor), and bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare). Woody plants are present, but are not dense in the area. Woody species include siberian elm (Ulmus pumila), elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), and dogwoods (Cornus spp.).

The prairie grasses are widely distributed across the area. The stand is sufficiently dense to dominate, but the growth of the native grasses is sometimes inhibited by accumulation of litter.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

The east and north sides of Herbert Hoover National Historic Site are bounded by the town of West Branch. Both residential and commercial structures are located near the park. Interstate 80 runs along the south side of the park. Farmland occurs beyond the highway and on the west side of the park. Corn and soybeans are the most commonly produced crops. Vegetation along the West Branch of Wapsinonoc Creek is similar to that along the creek inside the park.

Prairie Research

Landers, Roger Q. 1975. A report on the status and management of native prairie in National Parks and Monuments in the Midwest Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 126 pages.

Dr. Landers traced the history of the prairie reestablishment and commented on its condition in 1975. The condition of the prairie varied from excellent to very weedy. Few woody species had invaded but herbaceous weeds were thought to be a problem.

Landers, Roger Q. 1977. Reestablishment and management of native prairie areas. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 34 pages.

Dr. Landers also conducted a portion of his research on establishment of forbs from seeds and transplants on this site in 1976 and 1977. He cautioned against drawing conclusions from his research because of extremely dry conditions during the study. Direct seeding of forbs was less costly but less successful than transplanting seedlings started in the greenhouse.

Christiansen, Paul. 1982. Prairie inventory: Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. Cornell College, Mount Vernon, Iowa. 22 pages.

Dr. Paul Christiansen conducted a prairie inventory in August 1982. Five transects were sampled at four-rod intervals with a 20 x 50 cm quadrat. The Daubenmire method was used to score cover in 95 plots. He also established permanent transects for future comparisons. Big bluestem, indiangrass and switchgrass dominated the prairie. He recorded seven grasses and over 20 forbs.

General References

National Park Service. 1970. Master plan. Herbert Hoover National Historic Site/Iowa. 31 pages.

National Park Service. 1977. A special master plan study. Herbert Hoover National Historic Site/Iowa. 24 pages.

National Park Service. 1979. Statement for management. Herbert Hoover National Historic Site/Iowa. 12 pages.

National Park Service. 1982. Herbert Hoover National Historic Site/Iowa. A brochure. 4 pages.

National Park Service. 1982. Natural resources management plan. Herbert Hoover National Historic Site/Iowa. 10 pages.

HOMESTEAD

National Monument of America

Nebraska

Homestead National Monument of America is located on the claim of Daniel Freeman, one of the first applicants to file under the Homestead Act of 1862. Originally, the Homestead Act made it possible for settlers to claim farms of 160 acres (64 hectares) by paying a minor filing fee, building a house, living on the land, and cultivating it for five years. The monument commemorates the influence of the homestead movement on American history. It is also a memorial to the pioneers who braved the rigors of the prairie frontier to build their homes and fortunes in the new land. Homestead National Monument of America was established in 1936.

The monument consists of 194.6 acres (78.8 hectares). Federal land makes up 182.1 acres (73.7 hectares) and there are 12.5 acres (5 hectares) of nonfederal land. The park contains about 95 acres (38 hectares) of restored prairie (Figure 11). A detached area of school grounds, which is included in the total acreage, contains 1.2 acres (0.5 hectares) with approximately 0.7 acre (0.3 hectare) of prairie.

|

| Figure 11. Prairie map, Homestead National Monument of America. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: Bluestem Prairie (Andropogon—Panicum—Sorghastrum) (Map No. 74)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

Most of the nonwooded areas of what is now Homestead National Monument of America were plowed within a few years after being claimed by Daniel Freeman in 1863. These areas remained in cultivation through 1937. Undoubtedly, significant amounts of topsoil were lost through erosion during the seven decades of cultivation.

The area was seeded in 1939 to native grasses harvested in Gage County. This was one of the first, if not the first, attempt at revegetation with prairie species on National Park Service property. Few details were assembled concerning establishment following the first planting. Records show that a "good establishment" was obtained, and prairie sod was brought in to use on severely eroded spots. These spots were primarily in gullies on the hillside.

Records indicate a steady improvement in the prairie vegetation. Prairie hay and little bluestem seed were harvested in the early 1950's. Mowing and herbicides were used for weed control in the mid-1950's. Mowing was conducted every two to three years after seed maturity. A contract for prairie hay in 1965 allowed the entire prairie, except the southeastern corner, to be mowed. That was the last year that the entire area was mowed. Mowing and spot treatment with herbicides were used for weed control until 1978. No herbicides are presently in use.

Following unsuccessful attempts of weed control by mowing in 1967 and 1968, two attempts have been made to revegetate portions of the area. Approximately 10 acres (4 hectares) were seeded to prairie dominants in 1969 in an area southeast of the footbridge across Cub Creek. A portion of this area was replowed and replanted in 1975. Weedy species still dominated the area in 1983.

A prescribed burn was conducted on April 24, 1970 to control woody species and remove accumulated litter. The fire destroyed 70-75% of the eastern redcedar (Juniperus viriginiana) trees. Vigorous resprouting of many of the hardwood trees was an indication that one fire was not an adequate control measure. Some retrogression in the prairie vegetation occurred during the next 10 to 12 years. A 17 acre (7 hectare) portion of the area was burned by a wildfire in 1980. A second prescribed burn covering 8 acres (3 hectares) was conducted in the spring of 1982. On April 26, 1983, a prescribed burn covering over 100 acres (40 hectares) resulted in the successful removal of 90 to 95% of the accumulated litter and ground cover. Woody growth in the thickets was severely retarded.

The prairie can be separated into three general areas: (1) slopes to the south and southeast, (2) areas most recently planted on the level areas, and (3) the remainder of the level area. The slopes to the south and southeast contain good examples of prairie communities. Big bluestem, little bluestem, indiangrass, sideoats grama, and switchgrass are common grasses. Forbs include prairie rose, whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata), prairie clovers (Petalostemum spp.), slimflower scurfpea, and ground cherries (Physalis spp.). The prairie communities have had time to evolve. It is difficult, except for an experienced individual, to distinguish this area from an unplowed prairie.

A portion of the more recently planted area has never developed beyond the weedy stage. It contains only a scattering of prairie grasses. More common are weedy species such as prickly lettuce (Latuca scariola), common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), nettle (Urtica dioica), smooth bromegrass (Bromus inermis), bristlegrasses (Setaria spp.), and horseweed (Conyza canadensis).

The level areas are dominated by big bluestem, indiangrass, switchgrass, Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis), prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata), and other prairie grasses. Common forbs include goldenrods, wild licorice (Gylcyrrhiza lepidota), and roundhead lespedeza (Lespedeza capitata).

Woody plants are abundant (before the 1983 fire) on the level areas and, to some extent, on the slopes. Woody species include wild plum (Prunis americana), smooth sumac (Rhus glabra), eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), dogwoods (Cornus spp.), buckbrush (Symphoricarpos orbiculatus), elms (Ulmus spp.), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanicus), and mulberry (Morus alba).

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

The majority of the land surrounding Homestead National Monument of America is classified as agricultural. It is used primarily for the production of corn, wheat, alfalfa, grain sorghum, and soybeans. Vegetation along Cub Creek adjacent to the park is similar to the woody first and second growth within the park. A portion of the area bounding the northeast corner of the park is classified as residential.

Prairie Research

Landers, Roger Q. 1975. A report on the status and management of native prairie areas in National Parks and Monuments in the Midwest Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 126 pages.

Dr. Landers described the management history of the restored prairie at Homestead National Monument of America. He indicated that increasing woody species reduced the condition of the prairie. The southern slopes were considered to be the best example of prairie. Recommendations for management were included.

Stubbendieck, J., Richard Sutton, and Jayne Traeger. 1984. Vegetation survey and management recommendations for Homestead National Monument of America. Natural Resources Enterprises, Inc. Lincoln, Nebraska. 85p.

These researchers conducted a vegetation survey of the monument in 1982-84. The work included collecting species composition data, establishing photographic points, and establishing an herbarium. The information collected will be used to formulate long- and short-term management plans.

General References

National Park Service. 1978. Homestead National Monument/Nebraska. A brochure. 2 pages.

National Park Service. 1979. Interpretive prospectus. Homestead National Monument/Nebraska. 19 pages.

National Park Service. 1979. Assessment of alternatives. Natural resources management. Homestead National Monument of America/Nebraska. 68 pages.

National Park Service. 1980. Natural resources management plan. Homestead National Monument of America/Nebraska. 59 pages.

National Park Service. 1982. Resource management plan and environmental assessment. Homestead National Monument of America/Nebraska. 87 pages.

ICE AGE

National Scientific Reserve

Wisconsin

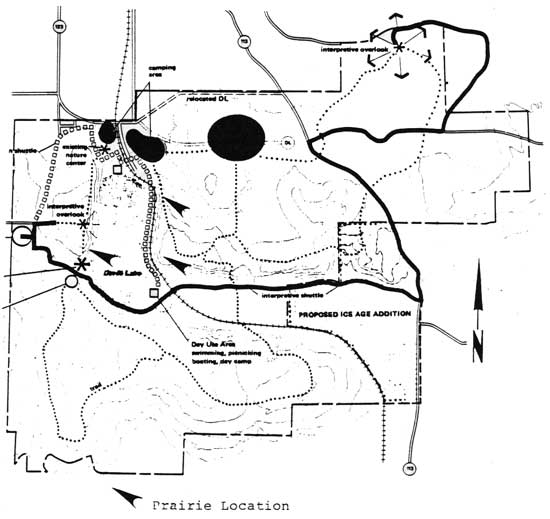

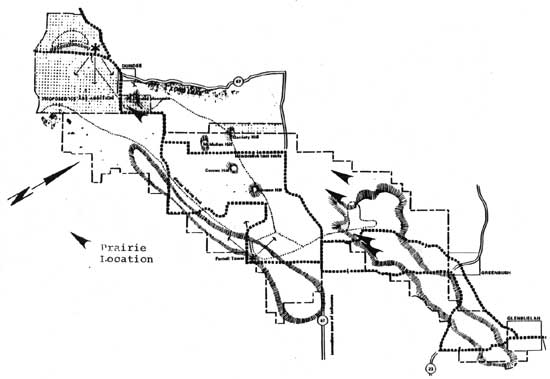

Ice Age National Scientific Reserve was established in 1971 to assure the protection, preservation, and various nationally significant land forms that were shaped by the last stage of continental glaciation. It is composed of nine separate units spread across the State of Wisconsin from Lake Michigan to Minnesota. It is authorized to include 32,500 acres (13,158 hectares) of land to be managed by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The wide geographical distribution and variety of physiographic conditions of the Ice Age units makes possible a diverse plant population. Three of the nine units are thought to include prairie or prairie remnants. These units are Cross Plains, Kettle Moraine, and Devils Lake State Park (Figures 12, 13, and 14). Perhaps only 15 acres (6 hectares) of prairie occur in the Ice Age National Scientific Reserve.

|

| Figure 12. Prairie map, Ice Age National Scientific Reserve (Cross Plains Unit). |

|

| Figure 13. Prairie map, Ice Age National Scientific Reserve (Devils Lake Unit). |

|

| Figure 14. Prairie map, Ice Age National Scientific Reserve (Kettle Moraine Unit). |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: A mosaic of Maple—Basswood Forest (Acer—Tilia) and Northern Hardwoods (Acer—Betula—Abies—Tsuga) (Map Nos. 99 and 106)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

Devils Lake State Park. A dry prairie on the top of the south end of the east bluff is the site of a prairie restoration project where trees were cut and the stumps treated to prevent sprouting. It is an area of about 5 acres (2 hectares) bordering the edge of the bluff. Big and little bluestem are common on the site. Numerous prairie forbs are also present.

Cross Plains. About 2 acres (0.8 hectares) of prairie are present in three scattered areas in association with oaks and open fields with oaks. These areas were formerly crop and pasturelands. Big bluestem is the most common grass in the prairie areas.

Kettle Moraine. Kettle Moraine contains about 8 acres (3.2 hectares) of prairie in association with open fields and upland brush. These are areas of abandoned croplands on which the vegetation has evolved to the point where grasses are dominant.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

Land use within one mile (1.6 kilometers) of the boundaries is primarily agricultural. Portions of the areas are cultivated for crop production, and some are grazed by domestic livestock. Forest species outside the boundaries are similar to those inside the boundaries.

Prairie Research

No prairie research has been conducted in Ice Age National Scientific Reserve.

General References

National Park Service. 1973. Master plan. Ice Age National Scientific Reserve/Wisconsin. 93 pages.

INDIANA DUNES

National Lakeshore

Indiana

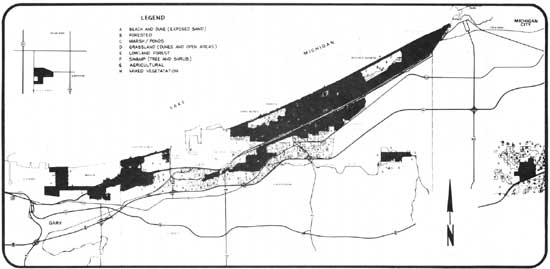

Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore preserves an important remnant of what was once a vast and unique lakeshore environment resulting from the retreat of the last great continental glacier some 11 thousand years ago. The park contains 15 miles (24 kilometers) of the Lake Michigan shoreline and 12,534.8 acres (5,074.8 hectares). Federal land totals 6,395.2 acres (2,589.2 hectares), and nonfederal land totals 6,139.6 acres (2,485.7 hectares). Immediately inland from the beaches, sand dunes rise to almost 200 feet (61 meters) in a series of ridges, blowouts, and valleys.

The Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was authorized in 1966 and formally established in 1972. Upland prairie exists in several units (Figure 15). Total area of prairie is estimated to be 989 acres (400 hectares). Prairie is located in the Cowles Unit, 570 acres (230.5 hectares); West Unit, 48 acres (19.6 hectares); and the East Unit, 36 acres (14.7 hectares). The Hooser Prairie Unit is about 335 acres (136 hectares) in size and contains excellent prairie. It is owned by the State of Indiana but is included within the authorized boundaries of the park.

|

| Figure 15. Vegetation map, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: A mosaic of Bluestem Prairie (Andropogon—Panicum—Sorghastrum) and Oak—Hickory Forest (Quercus—Carya) (Map Nos. 74 and 100)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

Where the dunes have been stabilized for some time, the predominant vegetation is oak forest. In the beach zone, however, some dunes are still active and all stages of vegetative succession can be seen.

The high, dry prairies include indicator species such as little bluestem and silky aster (Aster sericeus). Other species are Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea), tick trefoil (Desmodium illinoense), prairie junegrass, false boneset (Kuhnia eupatrorioides), slender yellow flax (Linum virginanum) and porcupinegrass. More mesic prairies contain indicator species such as big bluestem, compassplant, prairie dock (Sihium terebinthinaceum), and purple prairie clover (Petalostemon purpureum). Other species include leadplant, butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), blue aster, Atlantic indigo, rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium), white prairie clover (Petalostemum candidum), prairie phlox, indiangrass, porcupinegrass, and prairie dropseed.

Little active management of prairie has occurred at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Some protection from vehicles has been provided. Fire has played a major role in maintaining prairies in a climatic region supporting forest growth. Accidental and natural fires have burned large areas of the park. The Hoosier Prairie Unit is managed by the State of Indiana and is burned on a rotating basis.

Encroachment of woody species has been and will continue to be the most serious threat to the prairies. Use of mowing or herbicides for management has not been recorded. None of the prairies have been replanted.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

Complex patterns of land use surround Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Three residential communities are completely surrounded by the park. Major industrial complexes physically divide the park and flank it on both the west and east. Few significant prairie areas exist outside of the boundary. Common crops in the area are corn and soybeans.

Prairie Research

Research on the vegetation in what is now Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore dates back to the turn of the century. The early research was summarized in a literature review by Reshkin, et al. in 1975. The following is taken from that review (complete citations may be found in Section III of this report):

"As is commonly known, investigations in the Indiana Dunes played an important role in making ecology a modern dynamic science. Pioneering studies were made by Prof. Henry Chandler Cowles of the University of Chicago of the dunes along the southern and eastern shores of Lake Michigan. In his analysis published at the turn of the century Cowles (1899, 1901) presented evidence that plant communities of the dunes follow one another in a recognizable pattern: the dynamic concept of succession. One of Cowles' colleagues, Victor E. Shelford, an animal ecologist, soon followed up on this work (Shelford 1907, 1912a, 1912b) and described in detail how animals are intimately involved in this process of succession as well as exhibiting a successional pattern themselves. Virtually every American textbook in ecology, and many introductory biology books at both the high school and college level, describe the pattern of succession revealed in these studies and often include diagrams...."

"Being near to Chicago and offering a variety of unusual habitats, the dunes area was, and continues to be a mecca for naturalists. Particularly noticeable, both to the amateur and professional, was the unusual diversity of plant species in the dune region, and early papers noting this fact (Peattie 1922, 1926; Lyon 1927, 1930) were soon followed by a book by Peattie (1930) cataloging these plants. Numerous additions and updatings have since been made (Bushl 1934, 1935; Hull 1937, 1938; Tryong, 1936; Laughlin, 1953)...."

"Concurrent with the semipopular natural history interest there has continued a more scientifically oriented ecological interest. A series of publications by Fuller (e.g. 1911, 1925, 1934, and 1935) considered the relationship of succession to evaporation, adaptations of dune plants, and the general pattern of succession in the dunes area. . . ."

"Some of the most recent work, and at the same time a much needed modern review of the general aspects of succession in the dunes area, is that of Olson (1958). A concern underlying his work is that the pattern of succession described by Cowles, while carefully qualified by Cowles himself, had in its transmission over the years been highly oversimplified. Subjected to question in the first paper listed, in particular, is the commonly and expressed view that the substrate is modified by succeeding communities so as to be able eventually to support a mesophytic community dominated by beech and maple, the community usually considered climax for the area. Careful analysis of soils whose ages were determined by modern-day methods rather clearly discredits this notion. At the same time Olson uses modern sampling techniques to describe the dunes communities. Analysis of these descriptions in combination with age determinations reveal that there are many paths that succession may follow in the dunes with many variables influencing the pattern. . . ."

Jackson, Marion T. 1973. Evaluation of Hoosier Prairie, Lake County, Indiana, for eligibility for Registered Natural Landmark. Indiana State University, Terre Haute, Indiana. 346 pages.

This report describes the physical, climatic, vegetational features of the Hoosier Prairie. Special attention is given to the uniqueness of the prairie and of the prairie species.

Landers, Roger Q. 1975. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, In A report on the status and management of native prairie areas in National Parks and Monuments in the Midwestern Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 126 pages.

Dr. Landers delineated four types of prairie; prairie marsh, low prairie, mesic prairie, and high and dry prairie. He described the vegetation for each of these types. Six prairie areas were selected and included in a section of status of the prairies. The importance of fire as a management tool was discussed.

Wilhelm, Gerould S. 1980. Report on the special vegetation of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Research Program Report 80-01. National Park Service. 262 pages.

Vegetation is described. Individual species are listed by common and scientific name.

Krekeler, Carl H. 1981. The biota of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. In Ecosystem study of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Volume Two. Research Program Report 81-01. National Park Service. 340 pages.

This report summarizes the historical biological studies that were conducted in the area. The report also reports on the field studies conducted to obtain baseline data for the park. Methods are presented and plant communities are discussed.

Henderson, Norman R. 1982. A comparison of stand dynamics and fire history in two black oak woodlands in northwestern Indiana. Master of Science Thesis. Utah State University, Logan, Utah. 57 pages.

This research was conducted within the park boundaries. Differences in fire frequency and intensity were found to cause differences between two black oak (Quercus velutina) areas. Fire history in each area was determined through tree ring analysis of cross sections and wedges of fire scarred black oaks. Percentage cover and frequency of shrubs and herbaceous plants are listed by species.

Kerr, Kathryn, and John White. 1982. A vegetation research and monitoring program for a fire plan at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. National Park Service. 101 pages.

A program to monitor vegetation and fuel was established at the park during 1981. The program includes permanent vegetation sampling transects, photographic stations, and information for developing and applying a fire management plan and to provide baseline data for a long-term study of vegetation changes. This program will provide information on areas before they are burned. It also provides a means for making future comparisons regardless of whether the sites are burned. Methods are discussed and preliminary data are presented.

Reshkin, Mark, Herman Feldman, Wayne E. Kiefer, and Carl H. Krekeler. 1975. Basic ecosystem studies of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Indiana University Northwest, Gary, Indiana.

These studies were limited to the park boundaries. Descriptions of the plant communities are detailed. Vegetation sampling procedures are explained.

General References

National Park Service. 1971. Interpretive prospectus. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore/Indiana. 22 pages.

National Park Service. 1984. Environmental assessment. Improvements to headquarters area and horse trail. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore/Indiana. 35 pages.

National Park Service. 1976. Interpretive prospectus. West beach. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore/Indiana. 28 pages.

National Park Service. 1978. Preliminary information base. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore/Indiana. 178 pages.

National Park Service. 1980. General management plan. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore/Indiana. 63 pages.

National Park Service. 1981. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore/Indiana. A brochure. 8 pages.

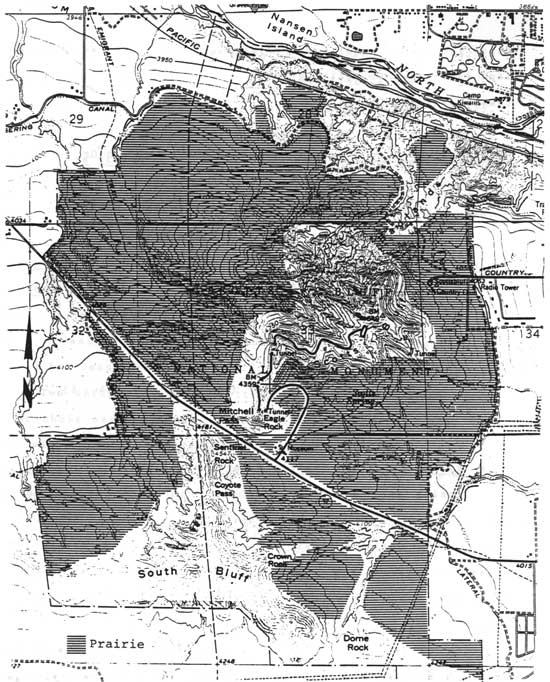

PIPESTONE

National Monument

Minnesota

Long before European man reached the northern plains, Indians of many tribes were traveling as many as 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) to quarry pipestone. This soft red stone is relatively easy to carve, even with primitive tools. The artist George Catlin visited the quarries in 1836. He was the first person to describe the quarries in print, and his pipestone sample was the first to be scientifically studied. Pipestone is called catlinite in his honor.

The Pipestone National Monument was established on August 25, 1937. On that date, the right to quarry pipestone was granted to Indians of all tribes. The park contains 281.8 acres (114 hectares) of federal land. About 260 acres (105 hectares) are managed as prairie, although this area includes about 20 acres (8 hectares) of rock outcrops (Figure 16). About 160 acres (65 hectares) is native prairie. The remaining 80 acres (32 hectares) are composed of go-back land that is undergoing succession towards a prairie climax.

|

| Figure 16. Prairie Map, Pipestone National Monument. |

Kuchler Vegetation Type: Bluestem Prairie (Andropogon—Panicum—Sorghastrum) (Map No. 74)

Present Vegetation and Prairie Management History

Management history of the Pipestone National Monument is rather sketchy. Prior to 1937, the vegetation would have been periodically subjected to fire, mowing for hay, and grazing. Heavy grazing was not uncommon. The western 80 acres (32 hectares) was subjected to cultivation until 1957. After establishment of the National Monument, mowing was used for weed control and general appearance maintenance.

Pipestone National Monument is located in an area where, historically, fire has had a great effect on the prairie vegetation. In the absence of fire, woody plants tend to invade prairie and to crowd out the natural vegetation. Prescribed burning was introduced as a management tool in 1973, probably in response to the effects of a wildfire in 1971 which burned southward along Pipestone Creek The basic design of the prescribed burning program was to burn all of the grass areas of the park once every five years on a rotating basis. Mixed grass, woods, and shrubs were to be burned for two consecutive years in each five-year period. The program has been extremely successful on many of the areas, especially the virgin prairie. Dominance of the native species was rapidly reestablished.

Pipestone National Monument is divided into 6 sections for the purpose of management. A brief description of the vegetation and burning management by section is as follows:

Section 1. This section is located in the southeastern portion of the park. It is native prairie, but it has been invaded by smooth bromegrass (Bromus inermis) and Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis). It contains many other invaders, including yellow sweetclover (Melilotus officinalis), white sweetclover (Melilotis alba), quackgrass (Agropyron repens), Canada thistle (Circium arvense), and red clover (Trifolium pratense). It was burned in the springs of 1974, 1977, 1981, and 1982.

Section 2. Section 2 is located along the southeastern and south central portions of the monument. It is native Bluestem Prairie, and it contains a few plants classified as negative indicators. Smooth bromegrass is common along the trail. The eastern portion was burned in 1973, 1976 and 1983. The western portion was burned in 1974, 1976, and 1983.

Section 3. Section 3 is located in the southwestern corner of the monument. The dominant plant species is smooth bromegrass. This area was cultivated before acquisition in the 1950's. There is no indication that this section was seeded back to native prairie species. Some scattered prairie plants are present, but the succession toward climax will be slow when smooth bromegrass is present, even with the use of prescribed burning. The southeast portion of this section was burned in 1984 and 1985 and all of this section was burned in 1974, 1978, and 1982.

Section 4. Section 4 is located in the northwest area of the monument. Smooth bromegrass and Kentucky bluegrass are the dominant species. Scattered prairie plants are present. This section has a history similar to that of Section 3. It was burned in 1974 and 1983.

Section 5. Section 5 is located in the north central portion of the monument. It is native prairie. It was burned in 1975, 1976, 1980, 1981, and 1985.

Section 6. This section is located in the northeast portion of the monument. It is also native prairie, and it was burned in 1976, 1981, and 1982.

Bluestem Prairie vegetation predominates in Sections 1, 2, 5, 6, and the eastern portions of 3 and 4. Occasional patches of smooth bromegrass and successional species are found in disturbed areas such as old road beds, the old railroad right-of-way, and formerly cultivated land. The existing native vegetation approximated the original prairie except for the presence of woody vegetation such as buckbrush (Symphoricarpos occidentalis), smooth sumac (Rhus glabra), wild black currant (Ribes americanum), chokecherry (Prunus virigniana), American plum (Prunus americana), sand cherry (Prunus besseyi), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), grey dogwood (Cornus racemosa), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa), and American elm (Ulmus americana). These woody plants are now starting to be controlled by burning.

The general status of the native prairie is good to excellent. Tall grasses and forbs are vigorous and produce many seeds. However, some of the exotic plants are not reduced and maintained by prescribed burning. Canadian thistle and sweetclovers are particularly difficult to control. Sweetclovers are currently cut or pulled. Spot applications of the herbicide Roundup (glyphosate) is used for Canadian thistle control. The go-back land is not in high condition. Complete restoration by seeding has been recommended for this area.

Land Use and Vegetation Within One Mile of the Park Boundary

The city of Pipestone is located on the southern edge of Pipestone National Monument. City property and the Pipestone Area Vo-Tech School bound the northeast side of the monument. A KOA Campground is located on the east side of the area, and the Hiawatha Club property is located on the southeastern portion of the boundary. Farmland is located on the southwestern and western boundaries. A State of Minnesota game refuge is located on the north boundary. National Park Service personnel have assisted the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources with prescribed burning of this area. Vegetation surrounding Pipestone National Monument varies with the diverse land use. Some prairie exists directly outside the boundaries, but it is in inferior condition when compared to that within the boundaries.

Prairie Research

Dr. Donald Becker, Ecosystems Management Inc., is currently conducting research on the prairie vegetation of Pipestone National Monument. A plant collection is also being assembled.

Moore, John W. 1956. A provisional list of the flora of Pipestone National Monument. University of Minnesota. Manuscript. 8 pages.

This list of plants was based upon Dr. Moore's "Provisional List of the Flowering Plants, Ferns, and Fern Allies of Pipestone County, Minnesota." The checklist contains both scientific and common names. Grasses are excluded.

Disrud, Dennis T. 1966. Plant collections, Pipestone National Monument. Manuscript. National Park Service. 3 pages.

Mr. Disrud was a seasonal employee during 1966. He made an extensive collection of vascular plants during the period of June 20 through September 6, 1966. His report indicates that ten species of fungi were also collected and identified. The presence of galls on various plants is also noted.

Holden, Max M. 1975. The importance of fire in maintaining native prairie vegetation in north central United States. Manuscript. 30 pages.

Mr. Holden assembled a literature review on the effects of fire on prairie. Pipestone National Monument is only mentioned in the manuscript. The manuscript contains ten photographs that were taken in conjunction with the 1973 prescribed burn at Pipestone National Monument. A sequence of photographs shows the development of the vegetation after the fire.

Landers, Roger Q., Jr. 1975. Pipestone National Monument, In A report on the status and management of native prairie areas in National Parks and Monuments in the Midwestern Region. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 126 pages.

Dr. Landers presented a rather complete review of the how the natural history of the area is related to the current prairie. Management history and the status of the prairie were discussed. He emphasized the importance of fire in maintaining prairie and reducing the woody plants. Dr. Landers management recommendations included the reestablishment of a prescribed burning program, methods to reduce invaders and methods to restore the prairie in Sections 3 and 4.

Landers, Roger Q., Jr. 1979. A report on management of native prairie areas, Pipestone National Monument. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. 34 pages.

History of the area surrounding Pipestone National Monument is outlined. Ages of the trees are discussed in relation to history and past management. Discussion of the prairie vegetation is divided into bluestem prairie, smooth brome and bluegrass successional, xeric, marsh, oak-elm woodland, and shrub. Prairie management recommendations are discussed. This report contains numerous color photographs.

Willson, G. D. and T. W. Vinyard. 1986. Changes in the lichen flora of Pipestone National Monument/Minnesota.

During September 1983 and July 1984, the authors collected and identified 65 lichens from the quartzite ridge at Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota. Forty-three of the 65 lichens were saxicolous (rock-growing) or terricolous (soil-growing), 21 species were corticolous (bark-growing), and one species was found on trees and rocks. They collected 35 new species and all but one of the species collected by Fink in 1899. They detected changes in the lichen flora by comparing their collections with those made before the area was forested. They believe corticolous lichens, which were not present in 1899, colonized the area from an eastern source. In contrast, they found the saxicolous/terricolous lichen flora had changed little during the past 84 years.

General References

Murray, Robert A. 1965. Pipestone—a history. Indian Shrine Association. 60 pages.

Pipestone National Park Service. 1971. Statement for management and planning. Pipestone National Monument/Minnesota. 7 pages.

National Park Service. 1976. Plan for the management of vegetation of the resource management plan. Pipestone National Monument/Minnesota. 6 pages.

National Park Service. 1976. Environmental assessment. Management of vegetation section, resources management plan. Pipestone National Monument/Minnesota. 21 pages.

National Park Service. 1978. Statement for management. Pipestone National Monument/Minnesota. 15 pages.

National Park Service. 1979. Pipestone National Monument/Minnesota. A brochure. 4 pages.

National Park Service. 1982. Resource management plan and environmental assessment. Pipestone National Monument/Minnesota. 54 pages.

Pipestone Indian Shrine Association. 1959. Circle trail. National Park Service. 15 pages.

Soubier, Clifford. 1971. Pipestone—a path, a stream, a wooded place. Pipestone Indian Shrine Association. 23 pages.

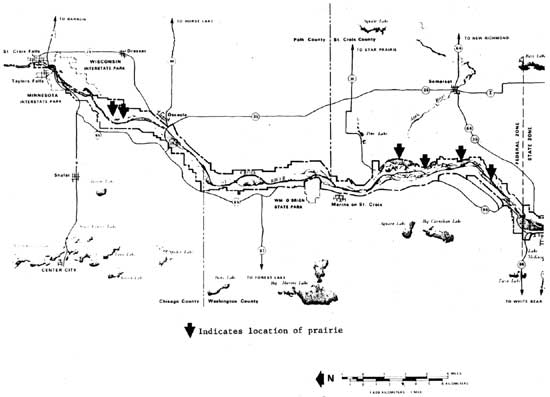

SAINT CROIX

National Scenic Riverway

Minnesota—Wisconsin

Free flowing and unpolluted, the Namekagon and St. Croix Rivers flow through some of the most scenic country in the upper Midwest. The Upper St. Croix and Namekagon portion of the Riverway is 200 miles (320 kilometers) long. It was established in 1968 as one of the original eight rivers under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The Lower St. Croix was added to the National Park System in 1972. It is 52 miles (83 kilometers) long. The park consists of 62,695.9 acres (25,383.0 hectares) in the St. Croix National Scenic Riverway and 8,670.00 acres (3,510.12 hectares) in the Lower St. Croix National Scenic Riverway. This figure does not take the islands into consideration.