|

Popular Study Series History No. 2: Weapons and Equipment of Early American Soldiers |

|

Equipment of the Soldier During

the American Revolution*

By Alfred F. Hopkins, Field Curator National Park Service

HOW did the soldier of the American Revolution keep his powder dry? What kind of musket and how many bullets did he carry? What other weapons and accouterments were included in the equipment of the fighting man?

These questions, which arouse a renewed interest today because the wars in Europe have redirected public attention to military arms, are answered by an exhibit on display in the museum of Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, N. J. The authenticated collection embraces most of the equipment with which the American soldier brought to a successful close the 7-year struggle for freedom.

This collection of equipment of the American soldier of the Revolutionary War includes a 1763 model Charleville musket, the regulation weapon of the French Army, with which most troops of the Continental Army were equipped by 1779. Felt hat, wooden canteen, powder horns, and ax are the other items in the case. |

An order of April 6, 1779, issued in Boston and now preserved in the Emmet Collection of the New York Public Library, describes in detail the arms and accouterments of that day. A copy of it in the Morristown exhibit reads:

To Shrimpton Hutchinson Esq.

SIR,

You are hereby ordered and directed, to compleat yourself with ARMS and Accoutrements, by the 12th Instant, upon failure thereof, you are liable to a FINE of THREE POUNDS; and for every Sixty Days after, a FINE OF SIX POUNDS, agreable to Law.

Articles of Equipment,

A good Fire-Arm, with a Steel or Iron Ram-Rod, and a Spring to retain the same, a Worm, Priming wire and Brash, and a Bayonet fitted to your GUN, a Scabbard and Belt therefor, and a Cutting Sword, or a Tomahawk or Hatchet, a Poach containing a Cartridge Box, that will hold fifteen Rounds of Cartridges at least, a hundred Buck Shot, a Jack-Knife and Tow for Wadding, six Flints, one pound powder, forty Leaden Balls fitted to your GUN, a Knapsack and Blanket a Canteen or Wooden Bottle sufficient to hold one Quart.

These prescribed articles, with the exception of the knapsack, blanket, and worm (the latter used in extracting the charge from the barrel of the musket should that become necessary), all are exhibited, bearing appropriate labels. Included in the display are—

(1) a hat of black felt, the brim rolled to form a tricorne, worn by Moe Judson, a soldier in the Revolutionary Army,

(2) a flint, steel, and tinder-horn, and

(3) two powder horns, the larger for containing the coarse powder for the barrel charge, the smaller to hold the more finely ground powder for use in the priming pan of the lock. Such horns were obtained from domestic cattle and used frequently when bullets and powder were not rolled together to form cartridges, the leaden balls and wadding then being carried in the pouch.

Musket cartridges, prepared by those skilled in their making, often were supplied to the troops from the ammunition laboratories. When they were not provided it was necessary for the soldier to "roll his own." He melted his lead and poured it into an iron mold, forming balls which numbered 12 or 16 to the pound depending on the caliber of the musket in which they were to be used. The handles of the mold formed a snipping device intended for use in cutting off the "neck" of the bullet after molding; but the soldier usually preferred to smooth the leaden pellet with his jackknife.

Excavations at the site of the soldiers' huts at Morristown uncovered many objects associated with the daily life of Washington's fighters. Pothook, forceps, knife, fork, spoon, buttons, and buckles are among the items pictured here. |

Into an oblong of tough paper he placed the ball, sometimes with four or six buckshot, and four or four and one-half drams of coarse, black powder which he rolled into a cylinder, twisting or tying the ends. After receiving a coating of grease for protection from dampness, the cartridges were placed in separate borings in the wooden block forming part of the cartridge pouch and covered by its flap of leather. The pouch, suspended by a shoulder belt of webbing or leather, was worn behind the right hip and usually held 24 cartridges or "rounds of ammunition." If the pouch and its contents became thoroughly wet during a rainfall or at a river ford, the soldier, except for his reliance on the bayonet, was hors de combat until his ammunition dried or a fresh supply of powder was obtained.

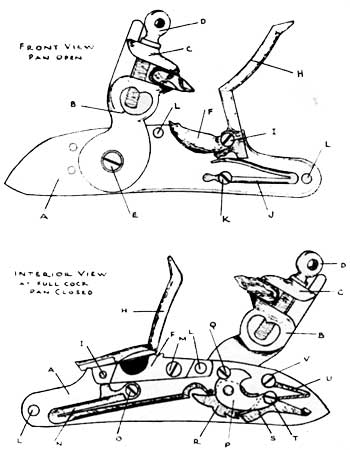

In order to load his musket when ammunition in the form of cartridges was used, the soldier brought the hammer of the lock to half-cock and uncovered the pan by pressing the frizzen upward and forward. (See diagram below.) Tearing or biting through the cartridge at its powder end, he filled the pan with powder, retaining it by closing the frizzen. Placing the butt end of the piece on the ground, he poured the remaining powder, together with the ball and paper as wadding, into the muzzle of the barrel and rammed them all well down with the rammer. Lifting the piece, he slapped it upon the stock opposite the lock in order to shake a small quantity of powder from the pan into the touchhole of the barrel. The piece then was ready to fire.

Tiny muskets and swords conform in minute detail to the arms of the Revolutionary period are being made by National Park Service museum preparators for display in realistic historical dioramas. |

If loose powder carried in horns was used, the soldier poured down the barrel a quantity that he considered to be the correct charge, dropped in a lead ball taken from his pouch and, with a twist of tow as wadding, rammed all downward. The pan of the lock was filled from the horn the smaller one usually containing more finely ground powder for promoting better ignition. To fire the piece the hammer was brought to full-cock and pressure applied to the trigger. The hammer, holding securely in its jaws a piece of flint, was brought down by the force of the main spring, and the flint, striking the steel of the frizzen, threw it forward, uncovering the priming powder in the pan into which a shower of sparks was sent at the same instant. The sparks ignited the priming, and fire passed through the touchhole of the barrel and to the charge inside. The bullet then went wobbling on its way from the smooth bore toward its mark.

The range of military muskets of the period was between 400 and 600 feet, depending on their origin, weight of ball, and quality and charge of powder. Because of their smooth bores they had little accuracy but were intended primarily for volley-firing at a distance not exceeding 300 feet. Yet, when a ball hit its mark after being fired from a musket of .69 or .75 inch in bore (the prevailing bores of military arms of the period), it was capable, if not too well spent, of inflicting death or serious injury.

From United States Martial Pistols and Revolvers, by Maj. Arcadi Gluckman, United States Army Mechanism of the Revolutionary Musket. a. lock plate; b. hammer; c. cap; d. hammer screw; e. tumbler screw; f. pan; h. frizzen; i. frizzen screw; j. frizzen sring; k. frizzen spring screw; l. side screw holes;; m. pan screws; n. main spring; o. main spring screw; p. bridle; q. bridle screws; r. tumbler; s. sear; t. sear screws; u. sear spring; v. sear spring screw. |

The musket shown in the illustration (top of page) is the French Army regulation arm of the period, the Charleville model of 1763. It was selected for display for the reason that by the time the order quoted above was issued in 1779 virtually all the American Army was equipped with this type. Together with other French regulation muskets made at the Royal Arsenals of Maubeuge, St.-Etienne, and Tulle, which differed only slightly in design, it was the finest military arm of its day. Manufactured with greater care and having an improved type of hammer and barrel securely fastened to the stock by bands instead of "pins" through lugs, it possessed greater durability, accuracy, and range than did the British musket, or the Colonial arms modeled from it, with which the Americans entered the war. The Charleville model was somewhat lighter than the British arm and its caliber was less, having a bore of about .69 inch.

If pressed, the trained Continental soldier could load and fire his piece four times a minute, but the rate generally was slower. He took little care in aiming, aware of the inaccuracy of his weapon except for short ranges. He swung his cartridge pouch to the front for greater accessibility; and between loading he thrust his ramrod conveniently into the ground beside him. His flint, if of good quality and adjusted properly between a fold of lead or leather in the jaws of the hammer, could be used 50 or 60 times. His handicaps were fouling of the barrel from powder combustion, which necessitated swabbing with the ramrod; and fouling of the flashpan and frizzen with clogging of the touchhole, requiring the use of a small iron brush and slender wire pick that usually were hung from the shoulder of the cartridge pouch or powder horn.

*Reprinted from The Regional Review (National Park Service, Region One, Richmond, Va.), Vol. IV, No. 3, March 1940, pp. 19-22.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Oct 20 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |