|

Popular Study Series History No. 4: Prehistoric Cultures in the Southeast |

|

Ocmulgee's Trading Post Riddle*

By A. R. Kelly, Chief, Archeologic Sites Division, Branch of Historic Sites, and Louis Friedlander, former student technician in history

IN 1936 archeological work under direction of Dr. Kelly on the middle plateau section of Ocmulgee fields, near Macon, Ga., revealed unmistakable evidence of what in all probability was a trading post established among the Creek Indians during the closing years of the seventeenth century by English traders working out of Charleston, S. C. The discovery came as a surprise because there were no known historical records concerning a trading post or a fort at this location for the early colonial period. An interesting archeological-historical problem thus presented itself.

In an attempt to establish by historical documentation the existence of a trading post of the Ocmulgee to agree with the evidence uncovered by the archeologist, a student technician, Louis Friedlander, of Columbia University, was assigned in 1938 to the task of examining the colonial records and archives at Columbia, S. C. It was believed that there, if anywhere, would be found documents bearing on the problem. He spent several weeks without finding a single direct reference to a trading post on the Ocmulgee near the present city of Macon. Sixteen volumes of the Calendar of State Papers for the period 1690-1715 were examined, but they yielded no specific information. It has not been possible to make anything approaching a complete examination of all the early South Carolina records because they have never been indexed and arranged in such form that they may be readily used. Considerable material was found, however, to substantiate strongly the inference that a trading post might have been established at Ocmulgee. For the present, there remains unsolved a fascinating problem of historical research, one which must receive further attention if we are to develop and interpret adequately for the public the potential contributions which this site has to offer in knowledge of the prehistory and history of the Southeast.

Dr. Verner W. Crane, Professor of History at the University of Michigan, an outstanding authority on the southeastern Indian frontier, in a letter dated September 30, 1938, comments on the lack of precise information in the early Indian books and colonial records regarding trading establishments. He states that he has found "Descriptions of trading posts in the South are practically nonexistent," and offers the suggestion that this is so, "probably for the reason that the references to them are made not by travelers writing for the general public, but by traders and agents in reports to persons who need no descriptions." He has suggested the Ocmulgee post may have been associated with the enterprises of a trader named John Bee who, according to Dr. Crane's own research, "maintained a trading factory on the Upper Ocmulgee for some years after the desertion of the Lower Creeks and in 1725 took out licenses for a 'parcel of traders' to the Choctaw."

The pentagonal base outline of the old structure at Ocmulgee National Monument is shown by the dark band of soil visible near the periphery of the cleaned area. The small square blocks of earth are control sections left around each stake of the grid system during excavation. |

The following résumé of the archeological findings at the site of the supposed trading post are taken from "A Preliminary Report on Archeological Explorations at Macon, Ga.," by Dr. Kelly, Bulletin 119, Bureau of American Ethnology, (Anthropological Papers, No. 1), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1938.

A FIVE-SIDED enclosure was worked out in its entirety. There was a broad base side, 140 feet long, facing the river toward the northwest. Two shorter sides or legs set at right angles to the base extended southeast 40 feet. The two remaining sides converged to form a triangle or gabled point directed southeast. The two sides forming the apex of the five-sided enclosure were 100 feet in length. The footing ditch, for such it was now perceived to be, had two breaks in its continuity in the base or front. One of these was 12 feet wide, the other 5 feet wide; they were apparently gates opening into the stockade from the river approach.

There were no remaining indications of decayed wood found except for the darker discolorations or black organic mold with thin discontinuous water-laid sand laminated between the darker soil areas. Vertical profiles through the footing ditch indicated horizontally laid logs probably pegged together. Early difficulties in planning the area to discover post molds were thus explained.

Inside the enclosure were rectangular areas of dark soil suggesting the decay of numerous logs. These were considered to be indications of what had once been cabins or storerooms.

Both in and around the enclosure were found burials of Indians of all ages and sexes, associated with European trade artifacts and objects of Indian manufacture, including pottery. A number of burial tracts not previously observed were encountered. The prevailing custom of primary flexed burials was noted, corresponding in this respect to burials at Lamar and other sites. However, the presence of artificial frontal deformation in a number of burials implied that this custom was much more prevalent in historic than in prehistoric times. Also several burials, again associated with European objects, were definitely cremated. The calcined bones had been heaped together and buried with guns, knives, axes, beads, iron ornaments, and other items.

In addition to the burials in and around the enclosure there were numerous indications of house sites in the form of broad oval wall continuities traced out from post-hole alignments. The tendency for large domestic pits to be located in the center of these simple timber houses was noted in several instances and generous quantities of pottery, animal bones, flint scrap, and artifacts, scattered European objects, including some glassware and crockery, were taken from the fill. The houses were small, usually not exceeding 15 feet in diameter, and were sometimes smaller.

The implied construction consisted of light sapling wall timbers probably bent and tied to form the roof, with brush or reeds covering the whole. Sod might have been used also but this was not evidenced in the debris.

In addition to the house sites there were uncovered numerous refuse pits not definitely associated with post-hole indications of house floors. Midden materials found in situ on the occupation level on which the houses were troweled out added to the data of exploration around the enclosures.

Another interesting feature was the profiled indication of a beaten trail terminating in front of the entrance to the trading post site. In profile the trail appeared as a ditch-like excavation 6 to 8 feet wide varying from 14 to 24 inches in depth. A bluish mucky clay fill in the bottom of the trail impression implied gradual deposition of clay sediments in stagnant water. The upper fill consisted mostly of water-laid or wind-blown sand.

The same trail indications had been followed at 50-foot intervals all the way across the plateau from a point at the extreme northeast rim margin beyond the outer dugout series north of Mound D to a point converging on the entrance of the trading post. The total extent of the trail thus surveyed was approximately three-quarters of a mile. Beyond the entrance to the enclosure the trail was picked up again in profile and carried southeast toward the river, dropping down from the plateau below the lower west slopes of Mound B. Beyond that point present explorations have not been attempted to trace the trail to its intersection with the river. In all likelihood river erosion has destroyed any vestiges in the plain below the plateau.

Another structural feature of importance was brought out in final exploration around the footing ditch. This was a moat-like ditch, separated by an average distance of 20 feet from the footing ditch, which indicated the line of the trading post stockade. The borrow ditch ran parallel to the footing ditch around four of the sides. It did not extend in front of the broadest or base side. The width averaged 10 feet with gently sloping sides; the depth varied from 2-1/2 to 3 feet. The fill showed a bluish mucky clay in the bottom with water-laid sands and loams in the top fill. Midden accumulations, refuse pits which had been cut through in the process of making the moat-like ditch, burials made in the floor after the excavations were made, all served to substantiate the view that the ditch was obviously related to the structure of the five-sided enclosure.

The quantity of European trade materials found in midden house site accumulations, and definitely associated with burials, indicated a rather numerous population of historic Indians living around a trading post which seemed at a later date to have been partly fortified. The interpretation of the moat-like ditch is still in doubt, although five-sided wall enclosures with moat-like ditches surrounding the walls were a frequent construction in the seventeenth and eighteenth century colonial fortifications of the Southeast. The cataloged European materials exhibited a large number of finds which were weapons of war. In addition to the guns, knives, swords, and pistols found with burials, there were scores of gun flints, molded lead bullets, brass buckles, buttons, and other objects suggestive of military equipment. In contrast with these materials were many trade objects, such as beads, clay pipes, coiled iron wristlets, and copper and brass sheets sometimes rolled into small funnels or into cylinders. Several burials of children and women with beads and other trade trinkets were cataloged from the area.

The field data previously summarized seem fairly conclusive to the effect that general exploratory trench explorations had come upon the site of a large and thriving trading post. The military character of many of the European finds seemed on first impressions to be too evident to suggest an ordinary establishment set up primarily for trade. The presence of 50 burials representing individuals of various ages and sexes denoted the existence of a stable population and probably a fairly sizable community, as these interments had been uncovered in only so much area as was represented in general trench exploration.

Pronounce It Oak-mull-ghee

ESTABLISHMENT in 1936 of a national monument embracing the rich archeological treasures of Ocmulgee Fields, an ancient Indian town situated at the edge of the present city of Macon, about 4 miles from the geographic center of Georgia, has brought that aboriginal name with increasing frequency to American lips. Many variants in pronunciation sprang up as the word spread farther and farther from the region of its origin.

Ocmulgee, meaning boiling water, is from the Hitchiti tongue, a dialect spoken among the Lower Creeks. It is pronounced as though spelled oak-mull-ghee (the g hard) with stress on the second syllable. That pronunciation is preferred by the Bureau of American Ethnology. It prevails today throughout the Ocmulgee River valley of middle Georgia.

According to Creek tradition Ocmulgee was the site of the first permanent Creek settlement after migration of the tribe from the West.

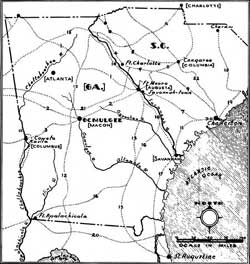

Trail System of Georgia and South Carolina—In

Early Colonial Days

(Adapted from a map published in the 43d Annual Report,

Bureau of American Ethnology, op. p. 748.)

THE following extracts from Mr. Friedlander's historical research report (typewritten manuscript, September 1938) on the Ocmulgee trading post problem indicate the general field of English and Spanish trade relationships with the southeastern Indians and the general character of Colonial rivalry involved in early white contact with the aboriginal occupants of what is now southeastern United States. Considering the historical circumstances of period and environment, the establishment and operation of a trading post at Ocmulgee would appear to be convincingly logical.

* * * * *

THROUGHOUT the Colonial period, the Indian trade was the chief instrument of Carolinian expansion. Its importance can readily be seen in the activities of Indian traders in attempting to win the friendship of the Lower Creeks away from their previous Spanish alliance to an English one. The urge of a highly profitable commerce led the English traders farther into the wilderness in this region, than they were wont to venture in the north. By 1700 "they were in contact and in keen rivalry not only with the Spanish of Florida, but also with the French in the region of the Gulf and the lower Mississippi."1

Many thousands of arrowheads, beads, and other objects have been uncovered by archeological excvations at Ocmulgee National Monument. |

The first Englishman to make contacts with the Creeks was Henry Woodward. Probably in 1670 and certainly in 1685, Woodward journeyed to the villages of the Creeks on the Chattahoochee. This was the region of their early home before their migration in 1690. It is safe to say that Woodward must have passed through Ocmulgee Fields on his journey westward—this being the shortest route to the Creek villages. But definite proof of this is lacking.2 We are certain though that "both at Coweta, the 'war town,' and Kashita, the 'peace town,' the English with their trading goods were cordially welcomed."3

The final victory of English diplomacy resulted in the movement of the Lower Creeks, about 1690, from their old home on the Chattahoochee to the region on the Upper Ocmulgee, the primary reason for this being that they would be closer to the source of the English trade and in a direct line with Charleston over the Lower Trading Path which connected with their settlement via Savanna Town (near present-day Augusta).4 It was the lure of cheap English goods that decided the contest between English and Spanish traders. Dr. Crane observes:

From the western river the Lower Creeks now migrated eastward to the upper waters of the Altamaha. Most of their new towns were placed along the Upper Ocmulgee River, known to the English as Ochese Creek. There for the next quarter-century was maintained the great center of the southern Indian trade. Goods for this trade were sent by packhorse, periago, or Indian burdeners, to the inland intrepot at Savanna Town, on the left bank of the Savanna at the falls. An early map shows also "the Old fort" on the right bank, near the site of Augusta. An outpost apparently, of the Carolina traders, this was probably the first English establishment upon the soil of Georgia. From Savanna Town . . . most goods were transported southwestward, by two trails which branched near the Ogeche River. One, the Upper Path, led to Coweta Town; the other, the Lower Path, to the settlements of the Ocmulgee and Hitchiti nearer the forks of the Altamaha. All Georgia, under Creek sway, was an English sphere of influence.5

Thus the importance of trade on the Upper Ocmulgee is clearly established. We should naturally expect to find numerous references to the establishment of a trading post at Ocmulgee Fields to substantiate the archeological evidence of one found by Dr. Kelly in 1936. But the lack of material on this particular point is surprising.

Until 1715 the English controlled the trade of the Lower Creeks. Governor Nathaniel Johnson showed a keen realization of the importance of their trade when he declared in an official report that the Cherokee were "a numerous people but very Lasey," and their trade inconsiderable in comparison with the flourishing southern and western trade of the Creeks who were described as "Great Hunters and Warriors and consume great quantity of English Goods."6

Not only was the Ochese Creek country important in itself for trade, but likewise "it soon became a base for the further extension of trade . . . From the Ocmulgee were sent out many of those slave-taking expeditions against Florida, and, later, against Louisiana, which provided on outlet for the warlike energies of the Indians, enriched the traders, and served to weaken the defenses of the rival Colonial establishment in the South."7

In 1708 the first commission to control the Indian trade was established in Charleston. The Journal of the Commissioners for the Indian Trade is an invaluable record and from it can be obtained the names of the traders with the Lower Creek Indians. The agents of the Commissioners and very often the traders themselves were required to make reports on conditions and the extent of trade among the Indians. These reports are not contained in the Journals and if they could be found they would almost certainly provide a wealth of material on the post at Ocmulgee. The Journals themselves are bare of material immediately relevant to a trading post at Ocmulgee Fields. The most important traders with the Lower Creeks, as indicated by the Journals, were John Chester, John Weaver, Richard Cower, William Britt, and Samuel Everleigh. All references to their names in the Journals have been followed but nowhere is an Ocmulgee post mentioned. Samuel Everleigh is especially important because it was he who supplied the traders with merchandise for the Creek trade.8

During Queen Anne's War (1702-1713) the region surrounding Ocmulgee became extremely important because it served as a frontier line between the Spanish and English spheres of influence. The anxiety of the colony in regard to the friendship of the Creeks is shown by a letter of Governor James Moore in 1702 in which he writes:

That you think of Some way to Confirm ye Cussatoes who live on Ocha-Sa Creek & ye Svannos in the place they now live in, and to our ffriendship they being the only People by whom Wee expect Advice of an Inland Invasion.9

In 1702 Queen Anne's War was precipitated in America by Anthony Dodsworth, often referred to as "Captain Antonio." It was he who led a force of 500 Creeks from Coweta to the Flint River to defeat the advancing force of Spaniards and their allies the Apalachees. Dodsworth is an elusive figure in the history of the period and conclusive evidence is lacking to the effect that he was ever at Ocmulgee. Nor can we be certain what part he played in Moore's expedition in 1703, although we know that it was he who urged the Commons House of the necessity of sending out the expedition. It was at the Creek villages on the Ocmulgee, the site now included in Ocmulgee National Monument and within which the archeological evidence of what is thought to have been a trading post has been found, that James Moore in 1703 fitted out his expedition in company with 50 Carolinians and concentrated 1,000 Indian allies on the meadows beside the post, armed them and proceeded south where he defeated a large force of Spaniards and Apalachee Indians.10

The Journals of the Commons House of Assembly record:

Coll. Ja. Moore be commissionated to Raise a Party of men to go to ye Assistance of ye Cowetaws, And other our ffriendly Indjans, And to Attacque ye Appellaches and allso to Concurr with this House in Sending a Present to ye sd Indians our ffriends And present the Same To this House To-Morrow Morning.11

The only letter we possess of James Moore at this time is a report to the Governor on his victory over the Spaniards and their allies, but it does not contain any information on Ocmulgee itself.12 Certainly Moore must have written back to the Governor from Ocmulgee or kept notes himself on the beginnings of the expedition.

|

Due to the culturally sensitive nature of the photo

that originally appeared in the document, this photo will not

appear in the on-line edition. All that remained of an ancient burial at Ocmulgee. Note rusty saber, ax, and other European trade material. |

Moore was a visionary Governor and he developed a conception of the destinies of England in this quarter of America far in advance of his time. Under his governorship South Carolina trade was actively fostered and, indeed, it was hard to distinguish between the leaders in trade and the leaders in government. He saw the necessity of destroying Spanish influence among the Southern tribes and his records are, therefore, especially important.

Sir Robert Quary, King's Commissioner of Customs stationed at this time in the South, has a good description of the consequences of Moore's expedition of 1703 and gives an enthusiastic estimate of the importance of his campaign in a report back to England.13 But this report also lacks definite information on Ocmulgee.

Research is aided by the fact that we can pin down the probability of establishing the post to within a definite number of years, that is, from about 1690 to 1715. The Creeks migrated to the Ocmulgee about 1690 and emigrated back to their old grounds on the Chattahoochee in 1715 after the Yamassee Wars.14 Governor Johnson's report to the Board of Trade in 1719 is interesting insofar as he records the beginning of the latter war. It says:

By the within Account of the Number of Indians Subject to the Government of South Carolina in the year 1715 Yo Lord ps will finde upwards of Eight and twenty thousand Souls of which there was Nine Thousand Men, which traded for above 1,000 lbs sterling Yearly in Cloth Guns Powder Bullets and Iron Ware and made return in Black Skins Doe Skins, Furs and other Peltry, and there was one or other near 200 English Indian Traders employed as Factors by Ye merchants of Carolina Amongst them; But in ye Said Year 1715 most of them rose in Rebellion and Murdered ye Said Traders & Severall of the Planters and their Family' that lay most exposed to them.15

While the information now known to us does not permit any definite or conclusive statement based on historical records regarding the question posed by the archeological discoveries at Ocmulgee, the weight of indirect evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that a trading post was established there among the Creeks by the Carolinian traders.

Notes

1 Verner W. Crane, The Southern Frontier (1928), p. 22.

2 Ibid., pp. 17, 35.

3 H. E. Bolton and Mary Ross, The Debatable Land, University of California Press (1925), pp. 48 if.

4 Verner W. Crane, op. cit., p. 34.

5 "The Origins of Georgia," The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 14 (1930), pp. 92-110.

6 Records of the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina, Vol. 5, p. 207.

7 Verner W. Crane, op. cit., p. 36.

8 Journals of the Commons House of Assembly, 1792, p. 133.

9 Journals of the Commons House of Assembly, 1702, Edited by A. S. Salley, p. 6.

10 Verner W. Crane, op. cit., p. 79.

11 P. 103.

12 This letter is reprinted in Carrol's Historical Collections of South Carolina, Vol. 2, pp. 574-576.

13 Contained in the Documents Relating to the Colonial History of New York, Vol. 4, p. 1088.

14 Records of the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina, January 12, 1719-1720, p. 235.

15 This migration is established clearly in Bolton & Ross, Spanish Resistance to the Carolina Traders, GHQ, Vol. 9, p. 115.

Bibliography

Adair, James, History of the American Indians, London, 1775.

Barnwell, J. W., "Dr. Henry Woodward' South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, Vol. 8, pp. 29-41.

Bartram, William, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, London, 1792.

Bolton, H. E., and Ross, Mary., The Debatable Land, University of California Press, 1925.

_______, "Spanish Resistance to the Carolina Traders in Western Georgia 1680-1704," Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 9 (1925), pp. 115-130.

Brannon, Peter A., "Coweta of the Lower Creeks," Arrow Points Magazine (Alabama Anthropological Society), Oct. 10, 1930-Feb. 10, 1933, pp. 37-47.

Calendar of State Papers—Colonial Series, America and the West Indies, Edited by N. Noel Sainsbury, London, 1901.

Candler, Allen D., The Colonial Records of the State of Georgia, Vol. 1, 1732-1752, Franklin Printing Co., Atlanta.

Carrol, B. R., Historical Collections of South Carolina, Harpers, New York, 1836.

Coulter, Merton E., A Short History of Georgia, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1933.

Council Journals (originals) 1671-1721. South Carolina State Archives—Office of the Historical Commission of South Carolina.

Crane, Verner W., The Southern Frontier 1670-1732, Duke University Press, Durham, N. C., 1928.

_________ "The Origins of Georgia," The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 14 (June 1930), pp. 92-110. "The Southern Frontier in Queen Anne's War," American Historical Review, Vol. 24, pp. 379-395.

_______ "The Origin of the Name of the Creek Indians," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 5, pp. 339-342.

Dunn, William E., "Spanish and French Rivalry in the Gulf Region 1678-1702," University of Texas Bulletin, No. 1705, p. 71.

Ford, Worthington C., "Early Maps of Carolina," Geographical Review,Vol. 16 (1926), pp. 264-73.

Gatschet, Albert S., "Towns and Villages of the Creek Confederacy in the 18th and 19th Centuries," Report of the Alabama Historical Commission, Vol. 1.

_________ "A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians," Library of Aboriginal American Literature, No. 4.

Harris, Walter A., "Old Ocmulgee Fields—The Capital Town of the Creek Confederacy," The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 19 (Doc. 1935), No. 4.

Jones, Charles C., The History of Georgia, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 1883.

Journals of the Commissioners of the Indian Trade (originals), Sept. 20, 1710-Aug. 29, 1718. (Printed for the period from Sept. 20, 1710, to April 12, 1715. Edited by A. S. Salley.)

Logan, John H., A History of the Upper Country of South Carolina, Vol. 1, Columbia, S. C., 1859.

McCrady, Edward, The History of South Carolina under the Proprietary Government 1670-1729, Macmillan, New York, 1897.

Morton, Ohland, "Early History of the Creek Indians," Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 9 (1931), pp. 19-26.

Quary, Robert, Letter to the Lords of Trade in Documents relating to the Colonial History of New York, Vol. 4, p. 1088 (New York Public Library).

Records in the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina, 36 volumes. Printed for the period from 1663-1690. Edited by A. S. Salley, Columbia, S. C., Atlanta, Ga., 1928.

Rivers, William J., A Sketch of the History of South Carolina to the Close of the Proprietary Government, McCarter and Co,, Charleston, 1856.

Salley, Alexander S., Jr., Narratives of Early Carolina 1650-1708. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1911.

Salley, A. S., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina. Edited by A. S. Salley.

_______ Journal of the Grand Council of South Carolina April 11, 1692-Sept. 26, 1692, Columbia, S. C., 1907.

Salley, A. S., Warrants for Lands in South Carolina, 1680-1692, Columbia, S. C., 1911.

_______ Warrants for Lands in South Carolina, 1692-1711, Columbia, S. C., 1915.

Shaftesbury Papers, Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, Vol. 5, Charleston, 1897.

Smith, Roy W., South Carolina as a Royal Province 1719-1776. Macmillan Co., New York, 1903.

Swanton, John R., "Early History of the Creek Indians," Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 73, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1922.

Wallace, Duncan D., History of South Carolina, Vol. 1, New York, 1934.

*From The Regional Review (National Park Service, Region One, Richmond, Va.), Vol. II, No. 1, January 1939, pp. 3-11. The collations are by Roy Edgar Appleman, Regional Supervisor of Historic Sites.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Oct 20 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |