|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Ecology of the Carmen Mountains White-Tailed Deer |

|

CHAPTER 1:

INTRODUCTION

Information on unexploited white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) populations is rare due to their popularity as game animals and to the lack of pristine ranges. Data from such populations would be of value because they serve as a base with which to compare exploited populations.

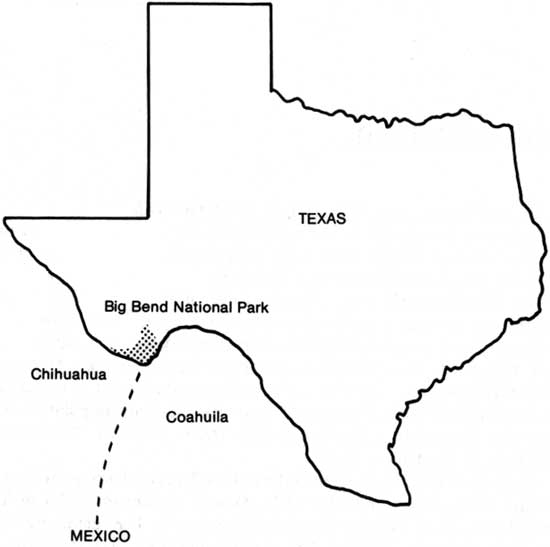

Big Bend National Park, Texas, is one of the few undisturbed ecosystems remaining in the Southwest and is unique in that it contains the only mountain range entirely within the boundaries of a national park. The Chisos Mountains rise abruptly from the Chihuahuan Desert floor to nearly 8,000 feet (2,440 m) and are the southernmost mountain mass in the United States. This range supports the main population of the Carmen Mountains white-tailed deer (O. v. carminis Goldman and Kellogg) in the United States.

Data on Carmen deer were collected for 3 years. During the first year of the study, beginning May 1971, Don E. Atkinson (1975) of Texas A&M University examined population numbers. The remaining 2 years of field work were conducted by me between June 1972 and April 1974.

Research reported herein was conducted to (1) evaluate specific aspects of the Carmen deer's ecology, including distribution, habitat, food habits, mortality, predation, and relationships with other ungulates, especially the desert mule deer (O. hemionus crooki Mearns); (2) provide knowledge as a basis for possible management; and (3) make available a source of interpretive information for visitors to Big Bend National Park.

Study Area

Big Bend National Park (Fig. 1) is a preserve representing the rugged northern Chihuahuan Desert. Dominated by expanses of Chihuahuan Desert interspersed with wooded peaks and river-swept floodplains, the Big Bend area provides some of the finest desert and mountain scenery in the United States.

|

| Fig. 1. Location of Big Bend National Park, Texas. |

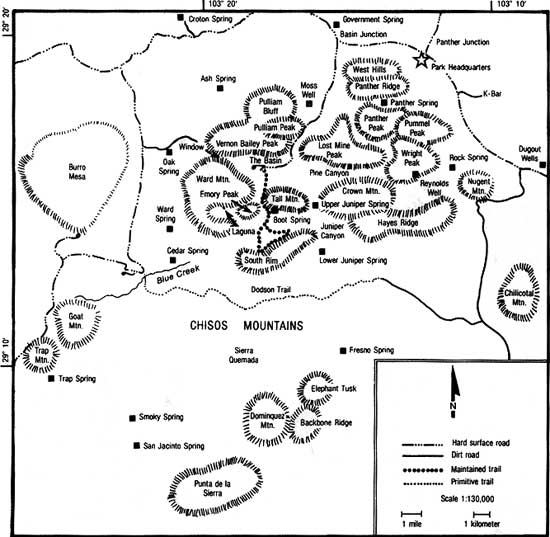

The Chisos Mountains lie between 103 and 104° longitude, and 29 and 30° latitude, and constitute the major locale for the present study. The entire park contains 708,221 acres (286,830 ha) but less than 2% constitutes the woodland community of the Chisos Mountains which lie above 4,500 feet (1,373 m) (Fig. 2). Higher elevations provide exclusive whitetail habitat but lower areas are shared with mule deer. The sympatric range is a band from approximately 4,000 feet (1,220 m) to 4,800 feet (1,464 m) lying along the face of sheer cliffs, canyons, and drainages.

|

| Fig. 2. Area locations in and around the Chisos Mountains. |

Physiography

Geology

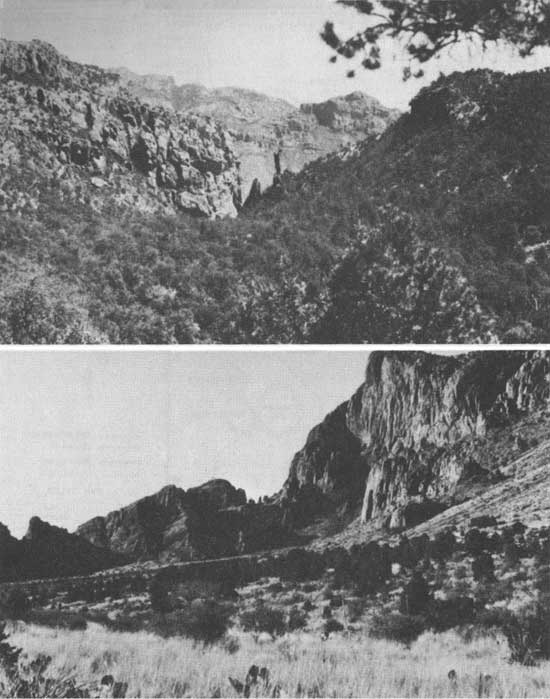

The igneous masses of the Chisos Mountains, Rosillos Mountains, and the cretaceous limestone formations of the Christmas Mountains break up the vast basin aspect of southern Brewster County. The Chisos Range, formed from differing volcanic origin, is an uplift of igneous and metamorphic material forming a circle of peaks roughly 5 miles (8 km) across (Lonsdale et al. 1955; Maxwell 1971). Rugged rock outcrops, vertical cliffs, deep canyons, and talus slopes are characteristic (Fig. 3).

|

| Fig. 3. Characteristic rock outcrops, vertical cliffs, deep canyons, and talus slopes of the Chisos Mountains. Top. Boot Canyon. Bottom. West of Pulliam Bluff along Green Gulch. |

The Chisos Mountains are the highest features in the park, rising from the 2,000-foot (610 m) desert plain to a maximum altitude of 7,825 feet (2,387 m) at Emory Peak (Fig. 2). The oldest rocks are volcanic ash, ash and clay, sandstone, and conglomerates. These are overlain by thick massive lava penetrated and deformed by intrusions. Both intrusive rocks and lava caps form the high elevations (Maxwell et al. 1967). The geology of the Big Bend Area is discussed in detail by Baker (1935), Kelly et al. (1940), and Maxwell et al. (1967).

Soils

Soils of the Chisos Mountains are primarily of the Ector, Brewster, and Reagan series. The Ector series are light brown, calcareous, friable, strong, and fine sandy loams, silt loams, and clay loams. This series supports sotol—lecheguilla (Dasylirion leiophyllum—Agave lecheguilla) and creosotebush—lecheguilla (Larrea divaricata—Agave lecheguilla) associations as well as several stands of pine (Pinus spp.) in the Chisos proper (Denyes 1956).

The forest communities of the higher life belts are found on fine sandy loams, silt loams, clay loams, and loams of the Brewster series. This series is brown or red, noncalcareous, and friable (Denyes 1956).

Reagan gravelly loam containing a 6- to 10-inch (15-25 cm) topsoil with abundant gravel is characteristic of the basal areas of the Chisos Mountains (Denyes 1956).

Climate

Hot summers, mild winters, and low rainfall are characteristics of the Chisos Mountains and surrounding foothills. Rains occur throughout the year, with the highest precipitation from May through October and with the greatest amounts recorded in August and September. Annual rainfall is about 13 inches (33 cm) in the higher mountains but occasionally exceeds 20 inches (51 cm). On the surrounding foothills, the annual rainfall averages 11 inches (28 cm).

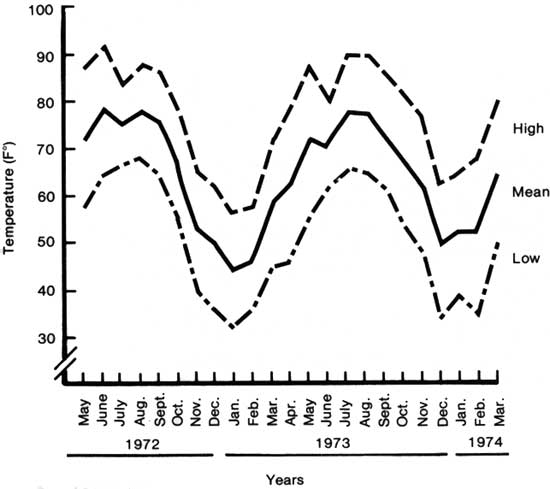

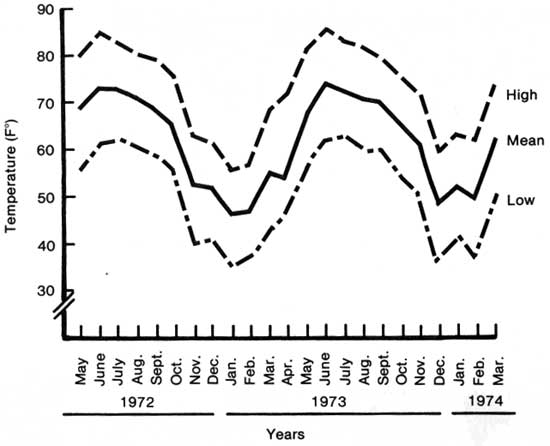

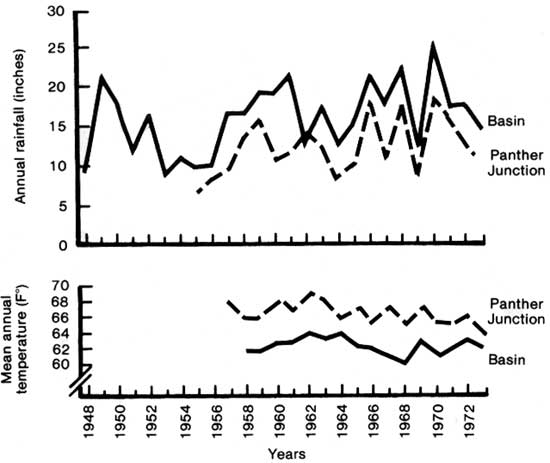

During the study period, the average maximum monthly temperatures during the hot months fluctuated around 80°F (27°C) in the mountains and 90°F (32°C) in the foothills (Figs. 4, 5). During the cooler months, frost and freezing were rare on the lowlands, while mountain temperatures dropped below freezing 20-30 times during winter (Wauer 1971). Snow is uncommon. Between 1948 and 1973, the mean annual temperature was about 66°F (19°C) in the foothills and 63°F (17°C) at higher elevations (Fig. 6) (Anon. 1948-74).

|

| Fig. 4. High, mean, and low temperatures for each month during the study period at Panther Junction. |

|

| Fig. 5. High, mean, and low temperatures for each month during the study period at the Chisos Mountains. |

|

| Fig. 6. Annual rainfall and mean annual temperature for the Basin and Panther Junction from 1948 to 1973. |

The upper mountains are watered by rain-fed springs in summer. Foothills obtain water from the spring runoff which is high due to torrential precipitation, scant vegetation, and nature of the soil (Muller 1937).

History of Land Use

Man's historic use of Big Bend is poorly understood but some information is available. Uncovered relics suggest that man entered the Big Bend Country before Christ and Indian civilizations existed but then vanished (Madison and Stillwell 1968; Wauer 1973). Spaniards entered the area as early as 1534, found it inhospitable, and bypassed the Big Bend on their westward expeditions (Taylor et al. 1944; Davis 1957). Relatively uninfluenced by man's activities, the area lay in a natural state until late in the 19th century. Even then, settlement in the Big Bend area was delayed as it became a haven for raiding Indians. In the 1880s the Indian threat passed and ranching activities began (Davis 1957). Livestock operations encircled the Chisos Mountains in the sotol—grasslands of the lower foothills by 1920 but the inaccessible mountains received little use. Overgrazing prevailed in the foothills, and by the late 1920s the livestock had advanced into the higher elevations (Wauer 1973). Overgrazing may have been the most destructive influence to hit Big Bend. Cattle destroyed lecheguilla and grasses were placed in jeopardy by horses, sheep, and goats. Drought created a cattle die-off from 1916 through 1919 and ranchers realized that forage was adjusted to precarious climatic conditions. Grasses disappeared and desert vegetation invaded rapidly (Davis 1957).

As the economic value of the land decreased, the people of Texas decided to preserve this portion of the Chihuahuan Desert. Most of the ranches were purchased by Texas in 1942 but grazing privileges were maintained until 1944. During this 2-year period, excess livestock placed on the area augmented the detrimental effects already operating. From the time the land was purchased until ranching finally ended, cattle increased from 3,880 to about 22,000 head, and the number of horses increased from 310 to 1,000. Other livestock abuse was caused by 25,700 goats and 9,000 sheep (Prewitt 1947; Wauer 1973).

As early as 1934, the Chisos Mountains were protected when established as a State Park. Hunting was illegal but not completely eliminated until 1944 (Maxwell 1956; Davis 1957; Madison and Stillwell 1968). When land acquisition was completed, the area was presented to the Federal Government. Big Bend National Park was established on 5 July 1944.

Flora

Assigned to the Chihuahuan biotic province, the Big Bend region of Texas can be separated into two biotic districts (Dice 1943; Blair 1950): the Davis Mountains biotic district and the Chisos biotic district which includes Big Bend National Park.

Localized climate and rainfall, weathering and erosion of the mountains and lower slopes, and geological processes that formed the mountains all have had direct effects on the vegetation in the arid and semi-arid land of Big Bend (Maxwell 1971). Burnt pine stumps scattered in high areas of the Chisos indicate that fire also has affected vegetation. Characteristic associations are found in irregular belts related to altitudes and local air currents (Muller 1937; Maxwell 1971). Parts of the Chisos are barren, but forests prevail in areas that receive sufficient moisture, while the lowlands are eroded plains with the most severe temperatures, lowest rainfall, and sparsest vegetation.

Dominant plants in the foothills include pricklypear (Opuntia engelmannii) and related species, lecheguilla, century plant (Agave scabra), spreading fleabane (Erigeron divergens), spurge (Euphorbia serrula), gramagrass (Bouteloua spp.), sotol, silverleaf (Leucophyllum spp.), evergreen sumac (Rhus virens), acacia (Acacia spp.), yucca (Yucca spp.), mimosa (Mimosa spp.), basketgrass (Nolina erumpens), snakeweed (Xanthocephalum spp.), goldeneye (Viguiera spp.), mariola (Parthenium incanum), guayacan (Porlieria angustifolia), and mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa). In the higher mountains and extending to the lower slopes, oak (Quercus spp.) is abundant along washes, and three species of juniper (Juniperus flaccida, J. monosperma, and J. pachyphloea) are common with pinyon pine (Pinus cembroides).

The vegetation in Big Bend National Park has been divided into six vegetational formations by Wauer (1971): River Floodplain-Arroyo Formation, consisting of the arroyo—mesquite—acacia associations; Shrub Desert Formation, consisting of the lecheguilla—creosote—cactus associations; the Sotol—Grassland Formation; the Woodland Formation, containing deciduous woods and pinyon—juniper and oak associations; and the Moist Chisos Woodland Formation, which is composed of the cypress (Cupressus arizonica)—pine—oak association. The last three formations are in the main study area of this project.

Mammals

Big Bend National Park supports more mammals than the casual observer would expect. Seventy-five species of mammals have been recorded within the park, including 28 rodent species, 19 species of bats, 17 carnivores, 5 even-toed ungulates, 3 rabbit species, 1 opossum, and 1 shrew (Easterla 1973).

Little was known about deer in the Big Bend area prior to settlement. Bone fragments, Pre-Spanish in age, found in caves in Coahuila, indicate the utilization of Carmen deer by early Indians (Gilmore 1947). Other historical information relating to Big Bend's deer are sparse. Limited data have been recorded in an unpublished ecological survey of the park (Davis 1957). Most of the following information is from that report as discussed by Ross Maxwell, the first Park Superintendent of Big Bend National Park from 1936 to 1952, and George H. Sholly, Chief Park Ranger from 1946 to 1955. The comments of these men were supported by local ranchers and other persons consulted by the ecological personnel at the time.

From 1912 to 1934, the Carmen deer and desert mule deer were fairly common. Their numbers were sufficient to allow ranchers to make as much or more money from selling hunting rights as they did from ranching activities. Mule deer were preferred by hunters, and less than 10 whitetails were harvested each season due to the habitat whitetails occupied. Inaccessible areas, rough terrain, and plenty of mule deer precluded heavy hunting pressure on whitetails (Borell and Bryant 1942).

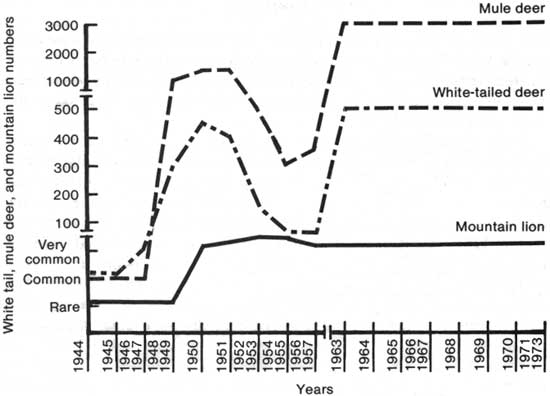

In 1941 and 1942, acquisition of the remainder of the present park area was accomplished and previous landowners were given until the end of 1944 to cease ranching and hunting. Apparently deer numbers were stable around 1936 but showed signs of increase from 1947 to 1952 (Murie 1954; Davis 1957) (Fig. 7). During the period from 1944 to 1957, Maxwell claimed the deer population was high. Counts of 70 whitetails and 50 mule deer during drives from the Basin down through Green Gulch, a distance of 13 miles (21 km), were common in the mid-1940s.

|

| Fig. 7. Population fluctuations of mule deer, white-tailed deer, and mountain lions from 1944-73 (based on NPS Annual Wildlife Reports). |

Several outbreaks of disease were described, the first in 1942, followed by an apparent decrease in whitetail numbers. Disease of unknown origin was again reported in 1944 and 1948. Ulcers in the mouth, stomach, and intestines were prominent symptoms. In August and September 1948, over 100 whitetail carcasses were noted in the Basin and adjacent areas. National Park Service records (Anon. 1945-present) indicated that stomach worms (Huemonchus spp.) may have killed deer in 1944 and undetermined poisonous weeds may have caused the die-off in 1945.

In the early 1950s, it was apparent that deer populations were decreasing. The decrease was blamed on mountain lion (Felis concolor) predation as the number of lions supposedly increased from 1949 to 1953 (Fig. 7).

Ranchers killed lions at every opportunity, and considerable time and effort was spent in lion control prior to the park's establishment; over 100 lions reportedly were killed in the Chisos Range between 1929 and 1942. Ranchers in the Rosillos Mountains north of the park reported killing 75-80 lions between 1947 and 1952. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service trappers took around 17 lions annually in the same area from 1954 to 1957. Random observations of lions at the time were numerous suggesting a considerable lion population.

Local residents were convinced that lion predation was the major factor for the decline of deer. This may have been an important factor, but other influences were working as well. Grazing pressure was intense prior to 1945 in the areas of high deer concentrations. The pressure was released in 1945 and was accompanied by abundant rainfall. Both range vegetation and deer numbers improved.

In 1944, whitetails were confined to the Chisos Mountains but were occasionally seen on Burro Mesa, Chilicotal Mountain, and Grapevine Hills (Borell and Bryant 1942; Anon. 1945-present). Numbers of deer in these areas were unknown but were probably low. Livestock operations established free-standing water in the form of earthen livestock water tanks and dug-out springs. New water sources may have allowed the deer to extend their range from the Chisos into surrounding hills and mesas. It is not known if deer occurred in these adjacent areas prior to water establishment. As the ranching years ended and water dried up, whitetails were no longer observed. Concurrent with the decline in ranching were the disease years of 1944 and 1948, which reduced the number of whitetails in the Chisos Mountains and probably added to the reduction on surrounding hills and mesas. A more important factor reducing whitetails in marginal habitat of the park may have been grazing pressure applied by introduced livestock.

In 1947, whitetails were observed on lower mountain bases, areas that had been grazed by goats and formerly unoccupied by deer. The whitetail increase through 1950 (Fig. 7) may have been due to range extension to lower foothills and high elevations.

The reduction of whitetails through 1957 (Fig. 7) was attributed to drought, lion increases, and reduction of free-standing water when ranch operators pulled out water tanks (Anon. 1944-73).

The reader should keep in mind that all census figures prior to 1955 were based on individual opinion, and quantitative measures were not considered in establishing numbers. An attempt was made to quantify measurements when pellet plot transects were established in 1955 and first read in 1956 (Davis 1957). The results of this attempt suggested that numbers of deer were not as low as previously believed. Figure 7 indicates the abrupt increase in numbers from 1957 to 1963. Historic observations of mammals and the 1950 transect work done in Big Bend have been the bases for deer estimates reported in National Park Service Wildlife Inventories and Fish and Wildlife Big Game Inventories from 1963 to the present.

Park rangers read pellet plot transects from 1968 through 1972 but did not analyze the results. Atkinson (1975) established new transects for estimation of deer in the park in 1971. The results of these studies will be presented later.

Park records indicate that ungulate and predator numbers increased when ranching and hunting ended. Table 1 summarizes the historic accounts of Big Bend's javelina and larger predators. Status estimates and numbers in this table sometimes conflict. Such inconsistencies are due to differing yearly assessments without a standard quantification method.

TABLE 1. Status of javelina and large predators from 1944 to 1973 in Big Bend National Park.

| Bobcat |

Mountain lion |

Coyote |

Javelina | |||||

| Year | Numbers | Status | Numbers | Status | Numbers | Status | Numbers | Status |

| 1944 | C |  | R |  | C |  | — | — |

| 1945 | C | — | R |  | C |  | R |  |

| 1946 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1947 | C | — | R |  | C |  | R |  |

| 1948 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1949 | C | — | U | — | C | — | 300 | — |

| 1950 | C | — | 15 | S | C |  | 300 | — |

| 1951 | C | S | 20-25 | S | C |  a a | 500 | — |

| 1952 | R | S | 40 | — | C | — | 200 | — |

| 1953 | R | S | 40 | — | C | — | 200 | — |

| 1954 | U | S | 30b | — | C | S | 200 | — |

| 1955 | U | S | 30c | — | C | S | 200 | — |

| 1956 | U | S | 10-15 | S | C | S | 250 |  |

| 1957 | U | S | 10-15 | S | C | S | 250 |  |

| 1958 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1959 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1960 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1961 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1962 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1963 | — | — | 17 | S | 400 | S | 3,500 | S |

| 1964 | — | — | 17 | S | 400 | S | 3,500 | S |

| 1965 | — | — | 17 | S | 400 | S | 3,500 | S |

| 1966 | — | — | 15 | S | 400 | S | 3,500 | S |

| 1967 | — | — | 10-20 | S | 400 | S | 3,500 | S |

| 1968 | — | — | 10-20 | S | 400 | S | 3,500 | S |

| 1969 | — | — | — | 400 | S | 3,500 | S | |

| 1970 | — | — | — | — | 400 | S | — | — |

| 1971 | — | — | — | — | 400 | S | — | — |

| 1972 | — | — | — | — | 400 | S | — | — |

| 1973 | — | — | 8-12d | S | 400 | S | — | — |

aReduction from illegal poisoning; b29 lions were also killed along park boundaries; c24 lions were also killed along park boundaries; dfrom Wauer (1973). C = common; U = uncommon; R = rare; — = no data;  = increasing; = increasing;  =

decreasing; S = stable. =

decreasing; S = stable.

| ||||||||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

15/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 08-Oct-2008