|

SAGUARO

Ecology of the Saguaro: II NPS Scientific Monograph No. 8 |

|

CHAPTER 1:

INTRODUCTION

Observe constantly that all things take place by change, and accustom thyself to consider that the nature of the Universe loves nothing so much as to change the things which are, and to make new things like them.—Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, "Meditations," 36.

Ours is a constantly changing environment and we most easily relate to and understand those responses that are immediate and that occur over a short span of time. As the time span of those changes increases it becomes increasingly difficult for us to relate to them, more so to understand them. We have particular difficulty understanding and accepting the observed effects of causal events that long pre-date our association with such results.

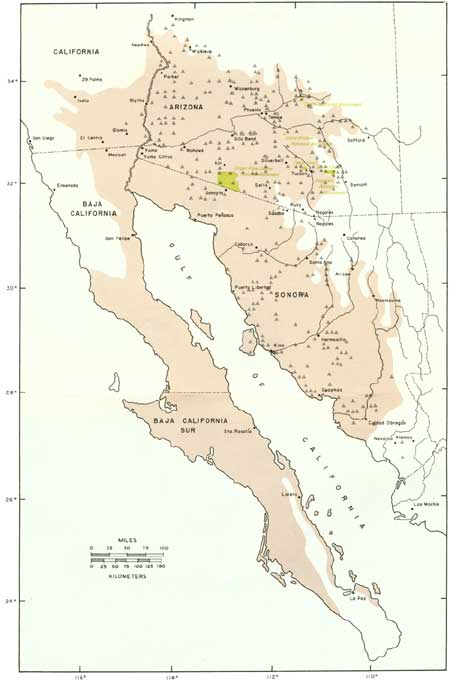

So it is with the saguaro, that we regard as a "problem" the dramatic fluctuations in some populations that we have witnessed during our brief temporal contact with the continuing process of evolution. With a maximum life span nearly twice our own, living saguaros have survived climatic events that long pre-date our recollection or knowledge. The species has survived through continuing environmental changes and has evolved during millions of years in environments that we have not experienced, and can but vaguely comprehend. However, examination of the question of what has happened, what is happening, and what will happen to the saguaro—at Saguaro National Monument and elsewhere throughout the range of its distribution in the Sonoran Desert—requires that perspective (Fig. 1). It is within the framework and perspective of the evolutionary process that we explore the ecology of the saguaro.1

1Investigations on the saguaro giant cactus (Cereus giganteus Engelm., Carnegiea gigantea [Engelm.] Britt. and Rose) reported here and elsewhere were independently initiated in 1951 by co-author C. H. Lowe. Subsequently, the work was continued with the support of the National Park Service (and others) in recognition of the need for basic knowledge of the biology of the species to provide information essential for ecologically sound management of the natural resources of Saguaro National Monument and other National Park System areas in southern Arizona. Vernacular and scientific names now most commonly used are saguaro and sahuaro, and Cereus giganteus or Carnegiea gigantea.

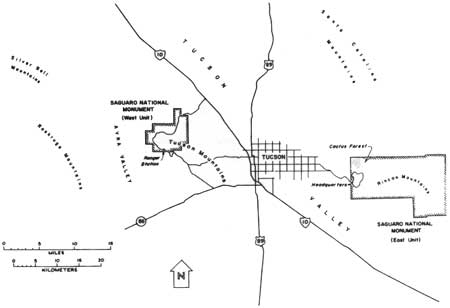

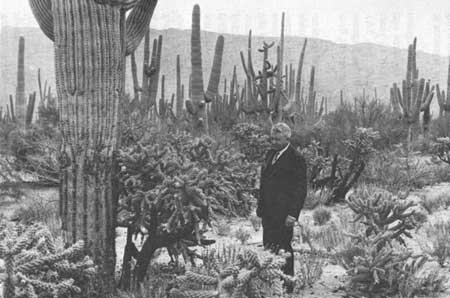

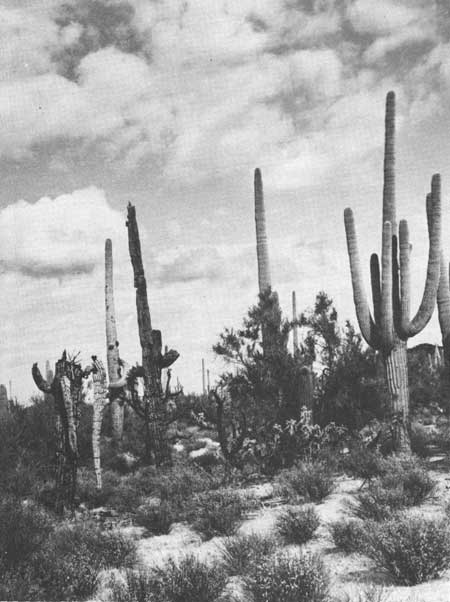

The National Park Service long has been concerned with the nature and cause of dramatic fluctuations that have altered grossly the structure of saguaro populations in certain portions of Saguaro National Monument (Fig. 2).2 In the Cactus Forest area of the original Saguaro National Monument, the once spectacularly dense concentration of giant old saguaros has dwindled in a few decades to an unimpressive population of sparsely scattered and dying old individuals (Fig. 3).

2Saguaro National Monument is comprised of two separate units situated on opposite sides of the Tucson basin. The original, Rincon Mountain Section (east unit), is located approximately 15 miles (24.2 km) east of the Tucson city center. The more recently established Tucson Mountain Section (west unit) is located about 15 miles (24.2 km) northwest of Tucson. Shelton (1972) provided a general description and account of the natural and human history of the Saguaro National Monument.

|

| Fig. 2. Vicinity map of Tucson and Saguaro National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

More important to the present and future condition of this population, however, is the relative sparsity of younger plants. That condition—the lack of sufficient younger saguaros to replace dead and dying older saguaros—insures absolutely that the number of large saguaros in this population will continue to decline.

The problem long pre-dates the establishment of the original Saguaro National Monument in 1933. The predominance of older saguaros and the lack of young individuals in photographs taken more than 40 years ago clearly reveal a population already many years in trouble (Fig. 3A). To a greater or lesser degree, other saguaro populations within Saguaro National Monument and elsewhere have undergone similar recent fluctuations (Figs. 4-6).

|

| Fig. 3A. Dr. Homer L. Shantz and the Cactus Forest as it appeared in 1930, immediately prior to establishment of the original Saguaro National Monument. The superlative quality of this stand—the abundance of large, old saguaros—together with the near absence of smaller, young saguaros clearly indicates a population already in trouble. Homer L. Shantz photograph collection, University of Arizona Herbarium. Photographed 22 Feb. 1930. |

|

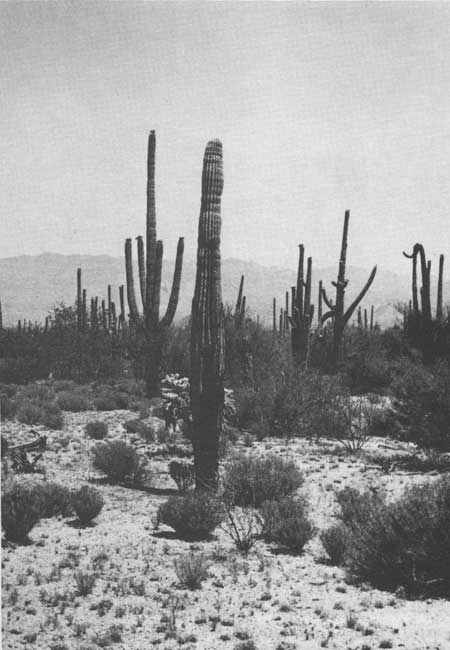

| Fig. 3B. Dramatic changes are evident in this view of the site shown in Fig. 3A, photographed 38 years later. In less than 4 decades, the forst of giant saguaros has been reduced to a few sparsely scattered individuals. No less significant is the death of all the chain-fruit cholla (Opuntia fulgida) present in the 1930 photograph. Photographed 19 Feb. 1968. |

|

| Fig. 4A. Overview of the Cactus Forest, Saguaro National Monument (east). The Castus Forest is situated in a gently sloping north-draining basin between the north-facing slopes of the Rincon Mountains (behind) and the south-facing slopes of the Santa Catalina Mountains on the horizon. Photographed 21 Feb. 1969. |

|

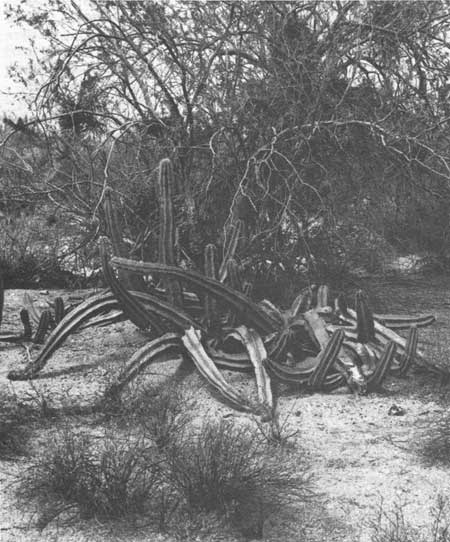

| Fig. 4B. Within the Cactus Forest, the die-off of saguaros continues in response to recurring catastrophic freezes. The abnormally slender stems and contorted form of moribund saguaros in the background, and the oozing black rot of the saguaro in the foreground are typical stages in the delayed collapse of freeze-damaged saguaros. As many as 9 years can elapse between lethal injury and the final collapse of a freeze-damaged saguaro. Photographed 28 May 1969. |

|

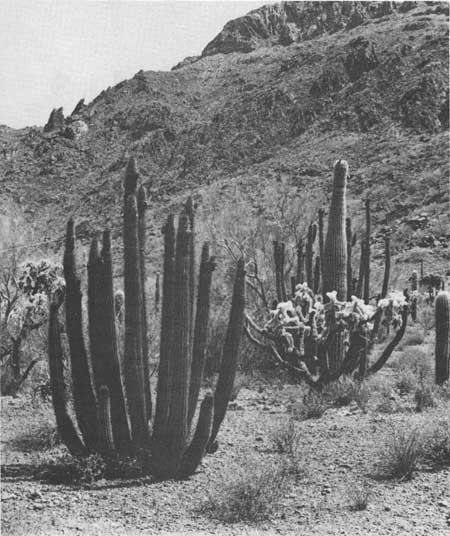

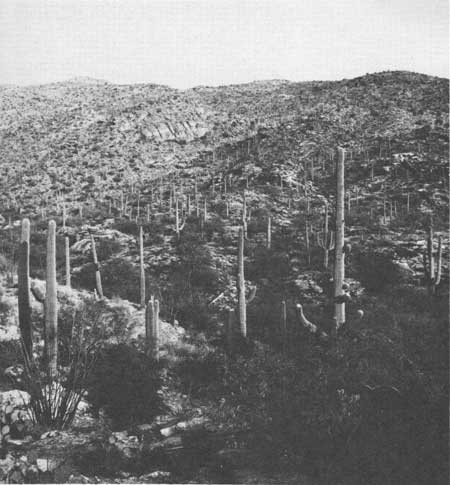

| Fig. 5A. At Saguaro National Monument (west), a dense and vigorous saguaro population occupies the rocky footslopes and upper bajadas of the Tuscon Mountains. Rock outcrops and the southwestern slope exposure mitigate extremes of winter cold. Photographed 28 April 1974. |

|

| Fig. 5B. January 1971 freeze-killed saguaros on the lower bajada at Saguaro National Monument (west). Here, in the Cactus Forest of Saguaro National Monument (east) and in other topographically similar situations, cold air drainage contributes to the severity of recurring catastrophic freezes. Photographed 21 Nov. 1971. |

|

| Fig. 6A. A young saguaro population on the eastern footslopes of the Tucson Mountains. A total of 48 juvenile and unbranched young adult saguaros is visible within the photograph. There are no living individuals of the parent generation on this southwest-facing slope. Photographed 2 April 1970. |

|

| Fig. 6B. An old saguaro population on the4 lower bajada at Saguaro National Monument (west). Compare with the nearby young population shown in Fig. 6A. Fluctuation in density and age-structure is characteristic of saguaro populations in the cold-limiting parts of the range of this subtropical species. Photographed 16 April 1971. |

In recognition of the needs of the National Park Service, our continuing investigations on the ecology of the saguaro are designed to provide definitive knowledge of the problem and to develop information essential for interpretive and resource management programs. Those portions of our investigations we report here concern the second aspect of the problem—the establishment, growth, and survival of the young saguaro. Our experimental designs and the hypotheses that they test are directed specifically toward obtaining information on the operation of natural selection through climatic and other physical and biotic factors that are critically limiting on saguaro populations.

More amazing perhaps than any aspect of its biology is man's emotional involvement with the saguaro—the saguaro is a "hero" among plants. He has endowed it with human attributes and bestowed upon it affection and concern for its "problems." Moreover, he has embraced myths, half-truths, and even eulogies generated by reporters and feature writers concerned more with the production of sensational and emotionally appealing "doomsday" stories than with the effective communication of accurate information. Cast in the role of a "dying hero," the saguaro has been accorded affection and credited with traits of character that have seriously beclouded general understanding of the true nature of its biology.

The truth in its great complexity lacks such direct emotional appeal. In place of such appeal, the truth offers a far more satisfying and significant understanding of a fascinating scheme for survival—the continuing process of evolution through millennia of natural selection in a rigorous and ever-changing environment. It is for those who find satisfaction in such understanding that we offer the results of these investigations.

While the concerns of the National Park Service are necessarily provincial, the answers to the question of the fate of saguaros in Saguaro National Monument transcend political boundaries to include the species population and the environmental factors that control the limits of its distribution. Thus we have examined and report here not simply upon our specific observations and experiments conducted within Saguaro National Monument and at the University of Arizona, but also upon our investigations and those of others made elsewhere throughout the range of the saguaro.

The question of what has happened, what is happening, and what will happen to saguaros at Saguaro National Monument is a long-standing one of primary concern to the National Park Service. Further, the answers to that question directly relate to the condition and management of saguaro populations at Tonto National Monument and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (Fig. 1).

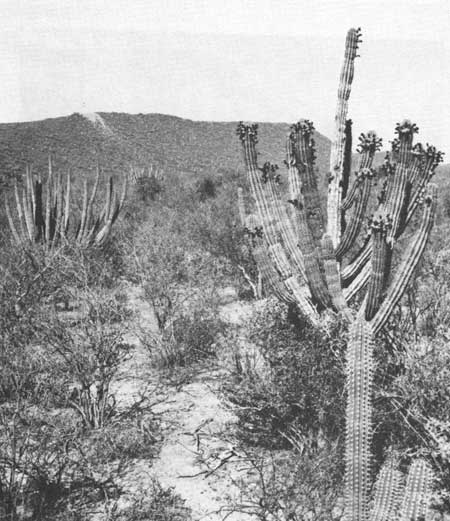

The applicability of these findings likewise is not limited by political boundaries; neither is the operation of factors that control the fate of the saguaro in the northern portions of its distribution in Arizona and northern Sonora limited in its controlling effects only to the saguaro. To a greater or lesser degree, the same factors are involved in controlling the northern limits of distribution and population dynamics of a large number of the tropically derived Sonoran Desert species in Arizona and Sonora. Particularly, many similar relationships occur in similarly evolved species of giant columnar cacti that reach the northern limits of their distributions either in Sonora or in adjacent southern Arizona: organpipe, senita, cardon, and hecho3 (Figs. 7-9).

3Organpipe or pitahaya (Cereus thurberi, Lemaireocereus thurberi); senita or old-man cactus (Cereus schotti, Lophocereus schotti); cardon (Cereus pringlei, Pachycereus pringlei); hecho (Cereus pecten-aboriginum, Pachycereus pecten aboriginum). See Benson (1940, 1950, 1969) and review by Felger (1970); Shreve and Wiggins (1964).

|

| Fig. 7A. The cold-intolerant senita cactus (Cereus schotti) reaches the absolute northern limits of its distribution in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in southwestern Arizona. Truncated and prostrate stems are the result of freeze-caused injuries. Photographed 7 May 1971. |

|

| Fig. 7B. The organpipe cactus (Cereus thurberi), only slightly more cold-tolerant than the senita cactus (Cereus schotti), occurs north of the United States-Mexico border almost entirely within and a few miles north of Organ Piple Cactus National Monument. Nearly every large individual in this northernmost part of its range bears a series of scars from recurring freezes. Photographed 12 July 1974. |

|

| Fig. 8A. The southernmost saguaros grow on the slopes of Cerro Masiaca, 48 km (30 miles) south of Navojoa, Sonora, Mexcio. On the slopes, it occurs with the closely related organpipe cactus (Cereus thurberi), left foreground) and hecho (Cereus pecten-aboriginum, right foreground). Photographed 7 Jan. 1972. |

|

| Fig. 8B. Cerro Masiaca and the southernmost saguaro population. The saguaros occur among basalt boulders and only on the south-facing slope of the hill—they do not occur on the adjoining plain. Subtropical deciduous thorn-forest, as seen in Fig. 8A, blankets the plains of southern Sonora and continues into northern Sinaloa on the distant horizon. Photographed 27 Dec. 1973. |

|

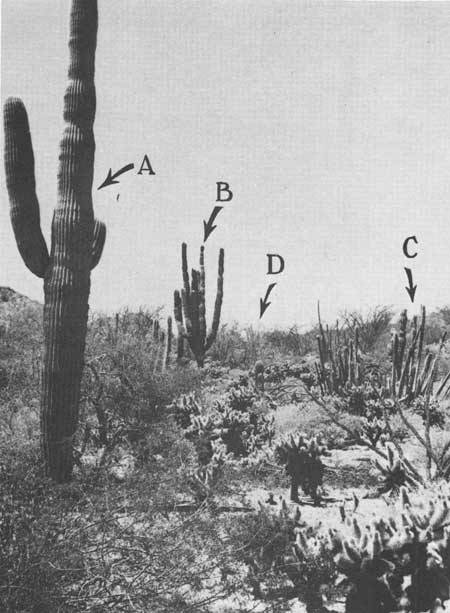

| Fig. 9A. The saguaro (left foreground and right background, arrow A) occurs with cardon (Cereus pringlei, arrow B), senita (Cereus schotti, arrow C), and organpipe (Cereus thurberi, arrow D) cacti in the vicinity of Puerto Libertad, and elsewhere along the Sonora coast of the Gulf of California. Teddybear cholla (Opuntia bigelovi) and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) are conspicuous in right foreground. Most of the associated plant species—but not the saguaro—also occur in Baja California, on the west side of the gulf. Photographed 19 April 1974. |

|

| Fig. 9B. Sparsely scattered saguaros grow with "desert riparian species," desert ironwood (Olneya tesota) and foothill paloverde (Cercidium microphyllum), at the western base of the Mohawk Mountains in Yuma County, southwestern Arizona. Along the moisture-limited westernmost boundaries of its distribution in the United States, the saguaro is associated with moisture-concentrating drainage channels. The nonriparian desert species conspicuous in the foreground are creosotebush (Larrea divaricata) and white bursage (Ambrosia dumosa). Photographed 13 April 1968. |

|

|

Fig. 10A. At the cold-limited

northern, eastern, and upper elevational extremes of its distribution in

Arizona and northern Sonora, the saguaro grows on south-facing slopes in

close association with boulders and rock outcrops. The northernmost saguaros (shown) occur at an elevation of approximately 1524 m (5000 ft) in Cottonwood Canyon approximately 3.2 km (2 miles) northwest of Hualpai Peak, Mojave County, Arizona. All of the 11 adult saguaros at this site grow against the base of the vertical south-facing cliff; 10 saguaros are visible in the photograph. Associated plant species on the rocky slope include Canotia holacantha (crucifixion thorn), Eriogonum fasciculatum (shrubby buckwheat), Larrea divaricata (creosotebush), Fouquieria splendens (ocotillo), Opuntia acanthocarpa (buckthorn cholla), Opuntia basilaris (beavertail cactus), Yucca baccata (banana yucca), Aplopappus laricifloius (turpentinebush), and Gutierrezia sarothrae (snakeweed). Photographed 4 May 1975. |

|

|

Fig. 10B. Vertical distribution of

saguaros on Tanque Verde Ridge (Rincon Mountains), Saguaro National

Monument (east). On this northwest exposure, the uppermost saguaros

grow at an elevation of approximately 1350 m (4400 ft). On the southern

slopes of these mountains, a few individuals grow in a rocky

south-facing canyon at approximately 1524 m (5000 ft) elevation. The saguaro species boundary line runs through the monument—the saguaro population at Saguaro National Monument (east) is a marginal one in every sense of the wood. Photographed 14 Nov. 1969. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap1.htm

Last Updated: 21-Oct-2005