|

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

Selected Papers From The 1987 And 1988 George Rogers Clark Trans-Appalachian Frontier History Conferences |

|

THE HENRY HAMILTON SKETCHES: VISUAL IMAGES OF WOODLAND INDIANS

J. Martin West

Fort Ligonier Association

Interest in the ethnohistory of Native America has grown markedly in recent years, but insufficient attention has been paid to the actual physical appearance of the Eastern Woodland Indian from the eighteenth century. For practically everyone, the only acceptable — and recognizable — visual image of any Native American is the mightily distorted and de-humanized product which has resulted from decades of American popular culture. Is there a national icon any more thoroughly familiar than that of the 1870s Plains Indian warrior? He embodies the romantic contradiction of savagery and virtue; impassive but noble; astride a pony, bedecked in buckskin, beads and paint; feathered war bonnet trailing down his back; and bow and arrow in hand, scanning the horizon dotted with teepees for signs of buffalo. One permissible variation is the southwestern Apache as depicted on celluloid in the 1950s, his clothing of fabric rather than leather, a cloth headband tied around his "Prince Valiant" wig and armed with a Winchester carbine possessing unlimited ammunition. According to the gospel of Hollywood and television, all Indians, regardless of chronology, locale, tribal background or tradition, looked basically the same in a timeless, unchanging way of life. Ignoring the facts that America's native peoples differed from each other as much or more as Spaniards differed from Finns or Greeks from Scots in Europe, and that their cultures underwent constant change and adaptation, this visual stereotype has gone practically unchallenged. It has been reinforced countless times by studio wardrobe departments providing "instant Indian kits" of indeterminate clothing, weapons and equipment that no Native American from the past would ever recognize. [1] This canard is accepted as literal truth by the vast majority of Americans, and by tens of millions of others around the world who have been exposed to the plethora of films and television programs originating in the United States which feature so-called Indians who, one can be certain, will remain "fixed in frame" for all time. [2]

This most prominent and graphic facet of the Pan-Indian myth presents serious problems in getting at the truth. An added complication is that since the academic disciplines of history, anthropology and archeology arose in the modern sense only after the eighteenth century, there exists substantial ethnographic material from the America of the 1800s and 1900s, but little from before. Consequently, the few attempts at reconstructing eighteenth century Indian appearance usually have been hindered by over-reliance on a culture basically trans-Mississippian and in existence long after the period in question, the aftermath of radical modification through European contact. The convenience and availability of these later sources is probably the reason that there has not been much serious study of the subject. However, that is little justification for perpetuating a stereotype in light of the intense scholarly interest in Native Americans and the historical reassessments of race relations in the past generation. The germane sketches, drawings, paintings and sculpture of Woodland Indians antedating 1800 that actually exist, can, if one takes the time to identify them, provide much useful information. They reveal varying levels of accuracy and authenticity and are, along with written descriptions by witnesses who actually saw Indians, and those few examples of material culture extant, all that there is in the way of dependable primary sources.

The bibliography offers only limited assistance. Three articles appeared in 1949, two of which were written by Frank Weitenkampf. In his "How Indians were Pictured in Earlier Days" he assigned just two brief paragraphs to the eighteenth century, criticizing the Indian work (executed in London) of American emigrant artist Benjamin West with the question "how much did he remember of crucial [racial] traits? [3] He made similar observations in his "Early Pictures of North American Indians, a Question of Ethnology," in which he dismissed most eighteenth century Indian portraiture "as conventionally European." [4] He also alluded to historian Howard H. Peckham's criticisms of West as an incompetent ethnologist whom, Weitenkampf agreed, imbued his subjects with "quite un-Indian-like" characteristics. The third article, "An Anthropologist Looks at Early Pictures of North American Indians" by John C. Ewers, is more original; he argued that the product of West and others seemed not so much an obtuse ethnocentrism but rather a suggestion that racial differences between Europeans and Woodland Indians may have been much more subtle and less pronounced than tradition would have us believe. [5] A good but brief overview of representative artwork appeared in 1958 by art historian Robert C. Smith, entitled "The Noble Savage in Paintings and Prints," based on an exhibition The Noble Savage at the University of Pennsylvania. [6] Another study, Philip Drennon Thomas' "Artists among the Indians 1493-1850," had little to say on the eighteenth century, but concluded that this period of Indian art was not a subject for serious study. [7] In 1982 James West Davidson's and Mark Hamilton's essay, "The 'Noble Savage' and the Artist's Canvas," appeared, which again concentrated primarily on the nineteenth century, but included a useful annotated bibliography. [8]

An important step forward was the fresh look given to material culture by examination of the context and significance of objects produced or utilized by Native Americans before 1800. One of the first examples of this approach was found in Dirk Gringhuis, "Indian Costume at Mackinac: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century" (1972), an introductory sketch that included color reproductions of eighteenth century native items. [9] In recent years there have been several excellent monographs highlighting Eastern Woodland objects and published in conjunction with professional museum exhibitions: Ted Brasser, "Bo'ou, Neejee: Profiles of Canadian Indian Art (1976); J.C.H. King, Thunderbird and Lightning: Indian Life in Northeastern North American 1600-1900 (1982); and David W. Penney, editor, Great Lakes Indian Art (1989). [10] In his 1984 dissertation, "His Majesty's 'Savage' Allies: British Policy and the Northern Indians During the Revolutionary War. The Carleton Years," Paul Lawrence Stevens presented a helpful listing of contemporary sources describing period Indian appearance, and called for some much needed attention to be given to this subject. [11]

European artists, going back as far as John White in the sixteenth century, saw Indians as symbols of another world, and as an exotic form of life discovered in a new continent. Historically accurate artwork is not easy to locate, some of it being the product of one's imagination, often based on second or third-hand accounts. By the time of the eighteenth century the rare painting that features an Indian usually shows a chieftain or historic event.

A good example of chieftain portraiture is that by Swedish-American artist Gustavus Hesselius, in his Chief Lapowinsa and Chief Tiscohan (1735). These individuals, Delaware participants in the infamous "Walking Treaty" of 1735, are quite realistic looking — weary and disillusioned — clearly showing the effects of European contact. [12] In the same vein was Joseph Brant, "the most painted Indian," and the subject of several artists including George Rommey, Gilbert Stuart and Charles Willson Peale. [13] It is Benjamin West, though, who is easily the most prominent of the artists who utilized Indian subjects. His Death of General Wolfe (1770) was the first full-scale history painting in which an accurate, historically correct Native American played a role. He quickly followed that with Penn's Treaty with the Indians (1772) in which half the subjects are authentic-looking Woodland Indians. West long has been condemned, often unfairly, for taking liberties with his history paintings. Dramatic license was an important aspect of the "Grand-style" school, but a thorough analysis of West's work reveals a careful sense of detail regarding his Indian subjects. The reason for such accuracy was revealed by West himself in letters from 1772 and 1805: "The leading characters which make the composition [Penn's Treaty] are the Friends [Quakers] and Indians — the characteristicks [sic] of both have been known to me from my early life . . . by possessing the real dresses of the Indians, I was able to give that truth in representing their costumes which is so evident in the picture of the Treaty." [14] One of West's students, artist John Trumbull, also produced several reliable Indian illustrations. [15]

Somewhere beneath the polished accomplishments of the above artists is the modest but important artwork executed by Henry Hamilton, the lieutenant governor of Detroit and superintendent of Indian Affairs, and later prisoner of George Rogers Clark at Vincennes in February 1779. Of Scottish descent, Hamilton first served as a British officer in the French and Indian War before receiving his North American command in the American Revolution. While on the latter assignment he seems to have cultivated an interest in drawing, producing landscapes and portraits, of which forty are known to exist. Hamilton's revisionist biographer, John D. Barnhart, appraised this small body of work to be of "little value either as historical documents or as works of art," except as it revealed the artist's character. [16] There are just eight existing Indian renderings, fragile and somewhat deteriorated, line drawings penciled on small gilt-edged cards. They were maintained by one of the lieutenant governor's collateral descendants and presented to Harvard University in 1902, where they form a part of a reference collection of Hamilton materials in the Houghton Library. [17]

It is suspected that Hamilton drew the Indian portraits from life at the time of the Vincennes expedition which, if so, fixes both date (between the late summer 1778 and February 1779) and locale (southeastern Michigan, northwestern Ohio and much of Indiana). These drawings exemplify the diversity of the different Indian nations, intermingled and refugees from the American war, which gravitated toward Detroit as allies of the British. Hamilton's "core sample" includes two Wyandots, a Mohawk, a Potawatomi, an Ojibwa, a Miami, a Nipissing and one drawing unidentified. It is indeed true that Hamilton's sketches intimate something about his own character. While he cannot be expected to be anything more than a man of his times, unlike most of his contemporaries Hamilton displayed a human sensitivity by portraying Indians as distinct personalities, replete with individuality and dignity. [18] Not only was he a relatively sympathetic observer of the Native Americans, but also as an artist he possessed a modicum of ability. Far more important than what they reveal of an eighteenth century European gentleman, Hamilton's sketches actually represent the opposite of the aforementioned historian's judgment; they may represent the best single source available of accurate depictions from life of actual Woodland Indians of the American Revolution and perhaps of the eighteenth century.

by permission of the Houghton Library

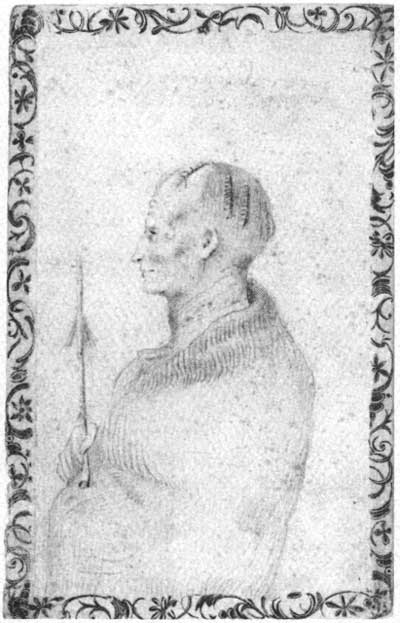

1. "Old Baby Ouooquandarong"

Hamilton's comment:

"This was a very wise and moderate Sachem of the Wyandot nation — his name in that language Ouooquandarong —" Ouooquandarong was a Wyandot, a northern Iroquoian group consisting primarily of Huron and Petun peoples. They were located in the Detroit area and also south of Lake Erie in the Sandusky and lower Maumee River vicinities.

His hair has been plucked out in the warrior's scalplock style, with what appears to be white wampum beads tied into three locks. He is wrapped in a fringed trade blanket. He holds a decorated calumet-pipe, one of the most revered objects in Native America. Tobacco smoke was venerated and employed in a ritual context for diplomacy, commerce, politics, trade, friendship and peace and war.

by permission of the Houghton Library

2. "Wawiachton a Chief of Poutcowattamie"

Hamilton's comment:

"This resembles strongly, Wawecaughton, a Chief of the Poutcowattamie nation —"

Wawiachton was a Detroit chief of the Potawatomi. They were an Algonquin people, many of whom lived with the Ojibwa and Ottawa. Their territory was the Detroit, St. Joseph and Wabash River regions, as well as southern Michigan, northwest Ohio and south of Lake Michigan.

He is dressed in a European wool cap and coat, edged with gold or silver metallic lace, the products of the Indian trade. Caps appear in contemporary trade lists, although most warriors preferred to expose the scalplock except in inclement weather.

by permission of the Houghton Library

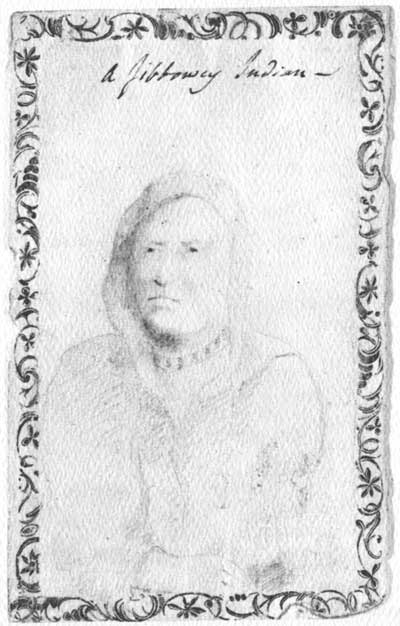

3. "A Jibbowey Indian"

Hamilton's comment:

Hamilton offered no additional information about this subject. The Ojibwa (or Chippewa) were a numerous Algonquin people, largest of the northern tribes, occupying a vast territory around Lake Huron. They were culturally related to the Potawatomi and Ottawa.

He is attired in a hooded blanket coat, cut in the European fashion. Around his neck is a purple and white wampum choker or neck band. Wampum was worked from a clamshell (Venus mercenaria), and was favored both for personal adornment and ceremonial usage.

by permission of the Houghton Library

4. "Skangress in Huron" "Otcheek in Iroquois"

Hamilton's comment:

"This man was a very respected warrior of the Mohawk nation — his name in the Huron or Wyandott language is Skangress — in the Iroquois Otcheek."

Skangress was a Mohawk living with the Iroquoian Wyandot. The Mohawks were "Keepers of the Eastern Door" of the Iroquois Confederacy in eastern New York State.

On his head is a raven skin, complete with head, beak and wings, and formed into the Iroquoian headdress, the Gus-to-weh. A purple and white (diamond) wampum choker is worn about the neck. He wears a "stroud" (a wool tradecloth mantle, blue, red or black in color).

by permission of the Houghton Library

5. Unidentified Subject

Hamilton's comment:

"I have forgot the name of this Indian, who was one of those characters, always to be found among the Indians — He travels from Village to Village, being provided with news, generally to suit his own views — they are termed bad birds, or birds of ill omen as their reports generally tend to intimate which they presume to be the best road to accomplish their views —"

Hamilton did not further identify him. He is wearing what appears to be either a hoodless wool blanket coat or a pullover smock. Tied around his head is a black or possibly red silk handkerchief from which a silver brooch dangles. The handkerchief as a bandana-like head covering was worn by Indians and frontiersmen alike in the eighteenth century.

by permission of the Houghton Library

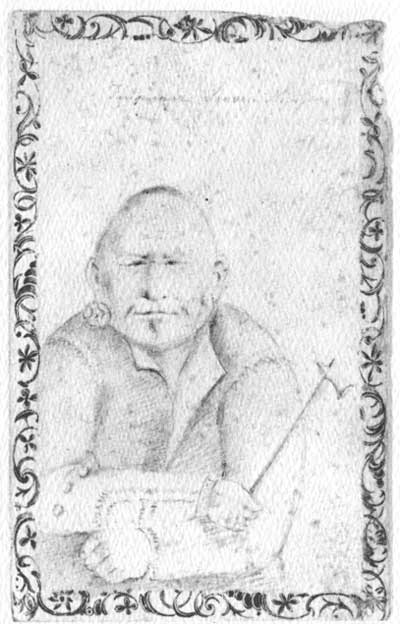

6. "Papiquenne Sauvage Nipissin"

"This is a savage of the Nipissin or lake of the two mountains about 19 miles above Montreal — his name Papiquenne which means the flute — his extraordinary resemblance to the Tartars is startling. He had but little character or authority, he was nearly a silent flute." Papiquenne was a Nipissing, an Algonquin people whose homeland was the environs of Lake Nipissing, the Lake of the Two Mountains (Montreal area) and the Ottawa River of Canada. Christianized, they often spent autumn with the Huron.

He wears the warrior's scalplock and, uncommon for a fighting man, a wispy mustache and tuft of beard. A silver ear wheel is suspended from his right ear. He is clad in a wool trade coat edged with fur. He is holding a pipe-tomahawk, emblematic of peace and war, which has an ax blade and functional pipe bowl making up the iron head.

by permission of the Houghton Library

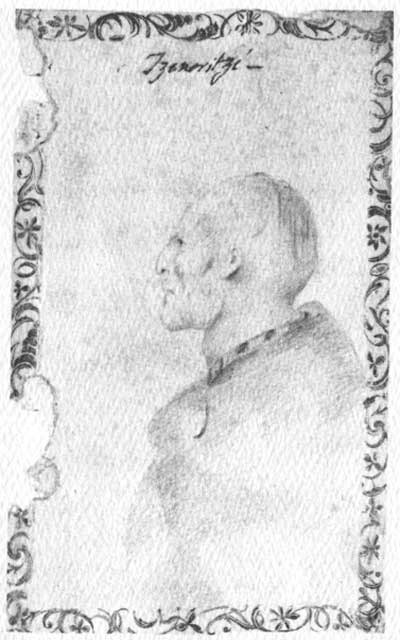

7. "Tzenoritzi"

Hamilton's comment:

"the nominal prince of the Huron or Wyandot Indians, a well disposed man who was easily led, given to Liquor, and not attended to in his Nation other than as hereditary chief, about 38 years of age." Tzenoritzi (Sastaretsi), also known as Dawatong, was civil chief of the Detroit Wyandot. Sastaretsi was a name title held by the Deer clan of the Wyandot.

He wears the scalplock and on his neck is a purple and white wampum choker, from which is suspended a round silver gorget perhaps engraved with personal or clan symbols. He is wrapped in the customary Indian garment of the period, the matchcoat, which to European eyes somewhat resembled the classical toga. Matchcoats commonly came in long pieces of white wool edged with blue or black stripes that could be cut to different sizes like blankets for men, women and children.

by permission of the Houghton Library

8. "Pacane Miamis Chief"

Hamilton's comment

"The name of this Miami Chief is Pacane — I made him a gift of silver mounted choteau (knife), his father of the same name having taken down from a stake when he was to have been roasted C[a]pt[ain] T[homas] Morris of the 17th Reg[iment] of Infantry, an acquaintance and friend of many years standing."

Pacane (the Pecan Nut) was head chief of the Atchatchakangouen group of the Miami at Kekionga (Fort Wayne, Indiana) during the Revolution. The Algonquin-Miami were culturally similar to the Illinois and Kickapoo, living in the general region of the Maumee and Wabash rivers drainages.

He is dressed at the height of Indian fashion. His scalplock and slashed ear represent his warrior status, the former decorated with silver ring brooches, the latter with silver ear wheels and wrapped flat wire around the distended ear rim. He is clad in a white linen trade shirt, with adjustable silver armbands above the elbows, and numerous silver ring brooches on the shoulders. Suspended from his nose is a beaded necklace of glass trade beads. He holds a pipe-tomahawk.

Notes

1Ralph E. Friar and Natasha A. Friar, "White Man Speaks With Split Tongue, Forked Tongue, Tongue of Snake," in Gretchen M. Bataille and Charles L. P. Silet, editors, The Pretend Indians: Images of Native Americans in the Movies (Ames, 1980), 93.

2Raymond William Stedman, Shadows of the Indian: Stereotypes in American Culture (Norman, 1982), 165. As Stedman pointed out, because of Hollywood, Native Americans are "all but frozen in their nineteenth century dramatic mold ...," 159.

3Frank Weitenkampf, "How Indians Were Pictured in Earlier Days," The New York Historical Society Quarterly, v. XXXIII, n. 4 (October, 1949), 216.

4Frank Weitenkampf, "Early Pictures of North American Indians: A Question of Ethnology," Bulletin of The New York Public Library, v. 53, n. 12 (December, 1949), 597-598.

5John C. Ewers, "An Anthropologist Looks at Early Pictures of North American Indians," The New York Historical Society Quarterly, v. XXXIII, n. 4 (October, 1949), 224.

6Robert C. Smith, "The Noble Savage in Paintings and Prints," Antiques (July, 1958), 57-58.

7Philip Drennon Thomas, "Artists Among the Indians 1493-1850," Kansas Quarterly, v. 3 (Fall, 1971), 7-8.

8James West Davidson and Mark Hamilton, "The 'Noble Savage' and the Artist's Canvas," The Art of Historical Detection (New York, 1982), 137-138.

9Dirk Gringhuis, "Indian Costume at Mackinac: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century," Mackinac History, II, Leaflet No. 1 (1972).

10Ted Brasser, "Bo'jou, Neejee: Profiles of Canadian Indian Art (Ottawa, 1976); J. C. H. King, Thunderbird and Lightning: Indian Life in Northeastern North America 1600-1900 (London, 1982); and David W. Penney, editor, Great Lakes Indian Art (Detroit, 1989).

11Paul Lawrence Stevens, "His Majesty's 'Savage' Allies: British Policy and the Northern Indians During the Revolutionary War. The Carleton Years" (Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York at Buffalo, 1984), Notes, Chapter 1, 1,858-1,859. Stevens' work, which runs some 2,496 pages, is a magnificent achievement of scholarship and can be considered definitive in its field. In his notes he offers insights and suggestions for additional research in many subjects, including the little-studied area of "the appearance of fashions of the northeastern Indians at the time of the American Revolution ...."

12E. P. Richardson, "Gustavus Hesselius," Art Quarterly (Summer, 1949), 220, 223.

13Milton W. Hamilton, "Joseph Brant — The Most Painted Indian," New York History, v. XXXIX (April, 1958), 119-132.

14Helmut von Erffa and Allen Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West (New Haven & London, 1986), p. 207. This monumental study provides the best and most complete analysis of Benjamin West's body of work, with excellent insight into his depictions of Native Americans. See 158, 206-207, 210-215, 219-220, 420-421.

15Helen A. Cooper, John Trumbull: The Hand and Spirit of a Painter (New Haven, 1982). For Trumbull's Indian work see 52-54, 130-133, 144-145, 150, 226-228.

16John D. Barnhart, editor, Henry Hamilton and George Rogers Clark in the American Revolution with the Unpublished Journal of Lieut. Gov. Henry Hamilton (Crawfordsville, 1951), 8-10, 206.

17The drawings are referenced: pf 115 Eng 509.2 H. Hamilton, the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

18Bernard W. Sheehan, "The Famous Hair Buyer General: Henry Hamilton, George Rogers Clark and the American Indian," Indiana Magazine of History, v. LXXIX, N. 1, (March, 1983), 5-8.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1987-1988/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 23-Mar-2011