|

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

Selected Papers From The 1991 And 1992 George Rogers Clark Trans-Appalachian Frontier History Conferences |

|

ZACHARIAH CICOTT, 19TH CENTURY FRENCH CANADIAN FUR TRADER: ETHNOHISTORIC AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON ETHNIC IDENTITY IN THE WABASH VALLEY

Rob Mann

Ball State University

Rick Jones

Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis

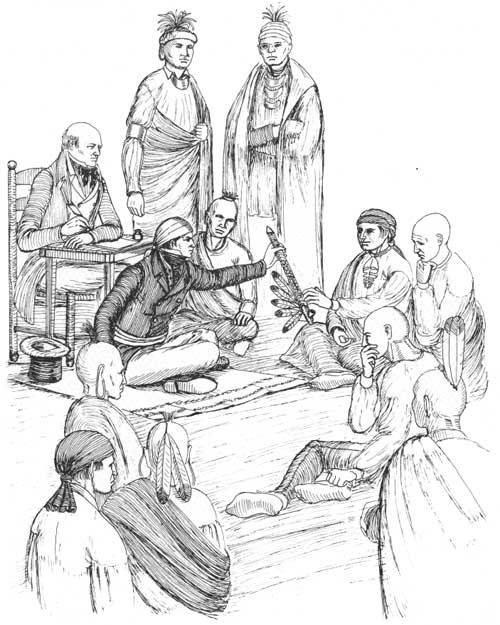

During the summer of 1991, the Warren County Park Board acquired the Cicott Trading Post Site. The property will be converted into an interpretive park. To this end archaeological investigations of the site were undertaken during the summers of 1991 and 1992. In addition, there is ongoing ethnohistoric research into the life and times of Zachariah Cicott, the French Canadian who resided at the site and who operated a trading post there from the early to the mid-19th century.

The site offers an excellent opportunity to study acculturation, the late fur trade, and French Canadians' adaptation and ethnicity during early territoria] and statehood settings. (Jones and Mann, 1992). This paper will examine the subject of ethnic identity, from both the ethnohistoric and the archaeological perspectives.

Ethnic identity can be defined as the "subjective symbolic or emblematic use of any aspect of culture, in order to differentiate" oneself from other individuals or groups. (De Vos, 1975:16). Contact with and interdependence on other ethnic groups do not lead to an erosion of ethnic identity. On the contrary, as Fredrik Barth has pointed out, "ethnic distinctions do not depend on an absence of mobility, contact and information, but do entail social processes of exclusion and incorporation whereby discrete categories are maintained despite changing participation and membership in the course of individual life histories." (Barth, 1969:9-10). In other words, Zachariah Cicott should have been able to maintain a sense of ethnic identity despite his interaction with an interdependence upon the British, the Americans, and the Native Americans.

Zachariah Cicott was born February 17, 1776, to Jean Baptiste and Angelique (Poupard) Cicott in Detroit. (Tanguay, 1887:67). Though officially a British possession after 1763, Detroit remained an essentially French community until after the War of 1812. The British, though not numerically superior, viewed the Detroit French with contempt. The same year that Zachariah was born, Detroit's Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton described the French as "mostly so illiterate that few can read and very few can sign their own names." He went on to say that although fish were plentiful in the river, "not one French family has got a seine — Hunting and fowling afford food to numbers who are nearly as lazy as the Savages." (Lajeunesse, 1960:84-85).

It is clear from the foregoing that boundaries existed between the French and the British. These barriers were maintained by just such statements which drew a distinction between "us" and "them." The French themselves maintained these boundaries by ascribing to a "set of traditions not shared by others with whom they are in contact." (De Vos, 1975:9). The marriage of Cicott's parents provides an excellent illustration.

The French habitants of North America generally adhered to the coutume de Paris in regard to civil matters. The coutume de Paris consisted of a compilation of customs, laws, and precedents passed to each generation as oral tradition. (Ekberg, 1985:186, 362). The coutume de Paris required couples to create a marriage contract which would insure the proper transmittal of family wealth. (Ekberg, 1985:186). The marriage of Jean Baptiste Cicott and Angelique Poupard occurred June 7, 1770, in Detroit. Their marriage contract revealed their adherence to the coutume de Paris. This holds that the couple's marriage be governed "according to the usage and customs of Paris, in express derogation of all other customs...." (Hamlin, 1879:76). Clearly, Cicott was born into what may be termed an ethnic community, one which held to its own traditional customs and institutions rather than to those of the dominant culture.

Although his father was a merchant, and a successful one if the 3,000-livre dowry promised to Angelique was any indication, (Hamlin, 1879:76), Zachariah sought to gain his fortune elsewhere. By his own recollection he arrived in Vincennes about 1792. (Henry, 1982:27). His arrival at that time may have been an attempt to bolster family land claims in the Vincennes area. (American State Papers [ASP], Public Lands, Vol. I, 1832:300; ASP, Public Lands, VII, 1860:705). Although Vincennes still essentially was a French village in 1792, many Americans had immigrated there during the years immediately following the Revolution bringing with them an economy based on the cultivation of large tracts of land. This prompted the French to petition the Congress for a donation of land during 1789. (Lux, 1949:441-445). Until that time, they had been, in their words, "chiefly addicted to the Indian trade" and "contented to raise bread for our families." (Lux, 1949:432).

John Heckewelder, who visited Vincennes the same year Cicott arrived, counted 30 American families living there. Just as their predecessors, the British, had done, the Americans viewed the French with contempt. Heckewelder described the French as being, "not accustomed to work and could not be taught how." Compared to the Americans, who he said dressed in linen and cotton, "there is hardly one among the French, who can dress himself decently, but whoever knows the Indian dress, knows theirs also." (Heckewelder, 1888:170).

Zachariah Cicott, then, spent his formative years in the French Canadian ethnic communities of Detroit and Vincennes. In both cases, the French Canadians were considered a distinct group by the prevailing powers. This distinction was recognized and was perpetuated by the French. In keeping with this, Cicott chose to enter the fur trade. As noted, the coming of the Americans brought many changes to the French at Vincennes. Chief among these changes was the decline of the fur trade. In their petition to Congress the French cited their "decreasing peltry trade" as one of the principal reasons behind the request. (Lux, 1949:442). Nevertheless, the fur trade continued to be a part of the Vincennes economy, though the Indians just were as apt to take their furs either to the British or to the Spanish traders. During 1788, John Francis Hamtramck, commandant at Vincennes, expressed his desire for more American merchants to come to Vincennes. He commented, "for if the Indians can not get their necessary supplys [sic] at this place they will go to the British...." He continued, "Linen is a capital article, a man with a good assortment of it would get all the peltry of the Illinois and of this place." (Thornbrough, 1957:77).

Cicott recalled beginning his trading activities about 1802 or 1804. (Goodspeed, 1883:37). The earliest documented evidence of his participation in the fur trade is an 1807 receipt for goods he purchased. Included on this receipt were 40 Jew's harps, several yards of calico, and various types of silk hanks, all of which clearly were items for the Indian trade. (Knox County Court Files, 1807). Cicott's decision to enter the fur trade, whether or not done consciously, was a reflection of his ethnicity. As Heckewelder somewhat caustically remarked, and as the French themselves acknowledged, Frenchmen first and foremost were fur traders.

Participation and expertise in a certain occupation can be ways in which members of a particular ethnic group define themselves or are defined by outsiders. Ethnohistorian Jacquiline Peterson has referred to the French Canadian traders and their metis families, who lived at Green Bay in present-day Wisconsin during the 18th and 19th centuries, as an occupational subculture. (Peterson, 1978:59). This subculture was characterized by Peterson as having consisted of a French-speaking Catholic population, largely intermarried with the local Native Americans. (Peterson, 1978:42). Cicott was all of the above.

Though his trading operation got off to a shaky start — Cicott was jailed in Vincennes for failure to pay his debts during 1809 and again in 1818 — he seemed to have found a niche by the early 1820s. (Henry, 1982:27). In 1824 and again in 1825, he was granted a license to trade with the Piankashaw, Wea, Kickapoo, and Miami Indians. (19th Cong., 1st sess., House Doc. 118; 20th Cong., 1st sess., House Doc. 140). The ledgers of Pierre Menard, of the Ste. Genevieve/Kaskaskia firm of Menard and (Francois) Valle, listed numerous transactions with Cicott or with his agents during this time. The entry for November 3, 1826, listed more than $1,500 worth of goods purchased by Cicott. Included on this list were more than 50 blankets, several varieties of cloth, several dozen knives, 500 gunflints, four kegs of gunpowder, and 150 small lead bars, to name only a few of the obvious trade items. (Illinois State Historical Society [ISHS], 1972).

Cicott continued to participate in the fur trade, or perhaps more aptly in the Indian trade, well into the 1830s. At the 1836 Potawatomi annuity payment, Cicott presented a claim for $4,800 which he withdrew during the investigation of a fracas which had erupted between rival traders. This situation brought a halt to the payment. (Edmonds, 1837:10). His withdrawal of this claim left questions as to its validity. This also may have marked the end of his trading career since he would have been 60 years old by that time and the claim was the last documentary evidence of his trading endeavors.

As alluded to above, Cicott indeed had followed the pattern of intermarriage established by generations of French traders. Peterson pointed out that by the 19th century French and Indian intermarriage was not due to a lack of European women, but rather it was a matter of choice. (Peterson, 1978:55). Marital alliance with influential tribal lineages was the most likely way for the independent trader to insure some degree of success. To this end, Cicott married an Indian woman, Pe-say-quot, sometime prior to 1816. She was the sister of Perig or Peeresh, a headman of the Not-a-wa-se-pee band of Potawatomi. (23rd Cong., 1st sess., Senate Doc. 512:344). Also known as Pierre Moran, Perig was reported to have been the son of the French trader Constant Moran and a Kickapoo woman. He became a chief of the Potawatomi by marrying into that tribe. (Robertson and Riker, 1942(1):371).

Pe-say-quot's Christian name was given as Marie on the 1816 baptismal record for her and Cicott's daughter, Sophie. (Burget, 1974:3). It is not known whether Pe-say-quot also was the daughter of Constant Moran. It is known that she was considered to be a Native American. The baptismal record for Sophie more specifically stated that on "April 29, 1816 I (Father G.J. Chabrat) baptised Sophie born Jan. 1 same year of legit marriage of Zacharie Chicot and Marie, a savage woman." (Burget, 1974:3).

This passage also shed light upon the nature of Cicott and Pe-say-quot's marriage. No official record of their marriage has been found yet and it is likely that the two were married a la facon du pays, (after the custom of the country) without the presence of a notary or a priest. Marriage a la facon du pays was derived from Indian practices. Once consent was obtained from the girl's parents and a bride price was paid by the trader, a ceremony involving native rituals occurred. The alliance between the trader and tribe then was sealed by smoking a calumet. (Van Kirk, 1980:36-37). These unions, though frowned upon by the clergy, were not so much opposed as counteracted. Thus, when a priest's services could be obtained, these marriages then were regularized in accordance with Christian practices while the Indian brides and any offspring duly were baptized. (Dickason, 1985:23). This may, in fact, be the process by which Pe-say-quot acquired her Christian name. This alliance seems to have had the desired effect for Cicott's trading operation peaked following his marriage to Pe-say-quot,

In addition to trading opportunities, by the 19th century intermarriage also offered access to large tracts of land by means of reserves granted to these families. Cicott and Pe-say-quot produced three children, Jean Baptiste, the aforementioned Sophie, and Umelia. (Robertson and Riker, 1942(2):595) By the Potawatomi Treaty of 1821, Jean Baptiste was allowed "the section of land granted by the Treaty of St. Mary's in 1818, to Peerish or Perig." (Henry, 1982:28). This reserve was located along the Wabash River in present-day Warren County, Ind., and surrounded the land upon which Cicott already may have established his trading post. The Cicotts again were granted reserves in the Potawatomi Treaty of 1826. Cicott received one section of land and each of his three children was given half of a section of land. (ASP, Indian Affairs, Vol. II, 1835:680). Clearly, Cicott and his offspring benefited from Pe-say-quot's Indian heritage. Though Pe-say-quot's fate is unknown, it is certain that sometime prior to 1838 Cicott took a second Indian wife, Elizabeth Isaacs. She was a member of the Brotherton band of Indians, a remnant Indian group from New York state. She and Cicott had at least one child, Susan Cicott. (Henry, 1982:28).

Sometime between 1817 and 1824, Cicott had done well enough in the fur trade to replace the "rude building" he had erected prior to 1812 with a larger, more substantial structure. It was in this building that Cicott raised his family, conducted his trade, experienced the death of at least one wife, and finally expired in 1850 at the age of 74. The cultural significance of this structure should not be underestimated.

As already has been established, Cicott was reared in what may be termed the French Canadian ethnic communities of Detroit and Vincennes. At Detroit, as throughout the remainder of French North America, a distinctive architectural tradition had developed by the time of Cicott's birth. French architecture in North America was characterized by the use of hewn vertical logs set either in the ground or on a sill. As French communities spread across North America, regional architectural differences developed. In the Detroit River region, historian Dennis Au found that by the last quarter of the 18th century, the poteaux surune solage, or posts-on-sill method, had replaced the earlier poteaux en terre, or posts-in-ground method. (Au, n.d.: 12-13). A poteaux surune solage house consisted of vertical logs mortised and tenoned into a wooden sill which, in turn, rested upon a stone foundation. The interstices between the vertical timbers were filled with either a clay-and-straw mixture, bousillage, or a stone-and-mortar mixture, pierrotage. The entire exterior then was whitewashed. (Au, n.d.: 12, Ekberg, 1985:286-287). Throughout the Detroit River region, pierrotage seems to have been the preferred filling. (Au, n.d.: 13).

A third style of French architecture, piece surpiece, may have been the predominate style in the Detroit River region from the mid-18th through the early 19th centuries. (Au, n.d.:15). This style was constructed by placing hewn horizontal timbers between vertical timbers which, in turn were mortised and were tenoned to a wooden sill. A distinctly French hallmark of each of these styles was the use of Roman numerals to mark adjoining timbers, thus indicating that these structures were "prefabricated" to insure a custom fit upon final construction. They also served as testimony to the fact that these structures usually were the work of professional carpenters. (Au, 1991b:11).

These three house styles would have been the most familiar to Cicott and if is likely that he lived in one or more of them while in Detroit and while in Vincennes. Heckewelder noted that in Vincennes, for instance, "The buildings of the French are all one story and instead of placing the smooth planks flat they are put upright against the frames upon which they nail them." (Heckewelder, 1888:170).

Heckewelder also made mention of another distinctive French architectural tradition, the palisade fence. (Heckewelder, 1888:168, 170). Carl Ekberg has noted the French insistence on having picket or palisade fences in colonial Ste. Genevieve, Mo. (Ekberg, 1985:285). These fences were used to enclose the houses, outbuildings kitchen gardens, and orchards of the French, while their livestock were left to roam freely. (Ekberg, 1985:285). The same appears to have been true of the Detroit River French. Dennis Au has described the French fences of this region as being "built of saplings and split rails about five feet tall, set a trench and secured to a horizontal rail near the top." (Au, n.d.:6).

These architectural styles and the unique use of fences were culturally significant to the French. These were two of the traits which helped define the French as an ethnic group. The historical archaeologist James Deetz has called the house the focus of that basic human social unit, the family. As such, the form of an individual's home "can be a strong reflection of the needs and minds of those who built it." (Deetz, 1977:92).

The ethnohistoric record shows that Anglo-Americans who saw Cicott's house did not know exactly how to describe it, referring to it both as a fort and as a blockhouse (Henry, 1982:31). Other sources commented on the unusual manner in which the house was constructed. Jacob Hanes, Sr., an early Warren County settler, described the house as being "built in 1817, the logs being hewn and shapen (sic) ready for putting up and boated here." (Hanes, 1880). During an 1886 interview, Patrick Henry Weaver, son of another early settler, claimed that Cicott's house had been framed from logs in Vincennes and had been brought in pirogues to present-day Independence, Ind., by Batise Seralyer. (Levering, n.d.:2). Yet another early settler, H.N. Yount, wrote in his reminiscences:

Cicot built him a log mansion, two stories high that was quite an imposing structure. This backwoods residence was made of logs carefully cut, hewed and numbered with Roman numerals, the whole arranged to form a house pattern when put up. (Yount, 1908).

These accounts hint at the possibility that Cicott's house was built in one of the aforementioned French styles. Unfortunately, the house is no longer standing and no photographs of it are known to exist. We must turn to archaeology to provide additional data.

Excavations conducted at the Cicott Trading Post Site (Indiana Site Number — 12Wa59) during the summers of 1991 and 1992 have revealed evidence which collaborates with the ethnohistoric accounts. During the 1991 season, more than 7,000 artifacts were recovered. (Jones and Mann, 1992:10-11). The trade silver, glass beads, buttons, gunflints, and the white clay and stone smoking pipes represented the tangible remains of Cicott's participation in the fur trade. They were an indirect reflection of that portion of his ethnic identity.

In addition to the artifacts, seven cultural features were uncovered, one of which was of particular interest. Extending at least 13.5 meters (approximately 14.8 yards) east to west and another seven meters (approximately 7.8 yards) north to south across the site was a narrow trench. Within the trench was a series of postmolds spaced about three to five centimeters (approximately 1.2 to two inches) apart. The postmolds ranged in diameter from five to 10 centimeters (approximately two to four inches). These features were interpreted as being the remains of a fence or of a palisade line. The smallness and nonuniformity of the postmolds indicated that saplings may have been used for the pickets. This palisade may have appeared similar to the one described above. Archaeologically, this same pattern has been found at a late 18th or early 19th century French Canadian house site on the River Raisin south of Detroit. (Au, 1991a:8). Unfortunately, the exact dimensions of Cicott's palisade line is not known, thus making further interpretations currently impossible.

Excavations during the summer of 1992 were centered on a portion of the site most likely to have contained the main structure. Although analysis still is in the early stages, preliminary observations suggest success. A linear concentration of limestone appeared to be the partial remains of the foundation. It extended roughly north to south across that portion of the site. Structural and architectural artifacts, including large amounts of nails and window glass, were associated with this feature. However, the most culturally significant artifacts recovered here may have been the mortar fragments or perhaps more appropriately, pierrotage. These fragments are identical in appearance to the pierrotage used in a posts-on-sill house built sometime during the early 19th century in Ste. Genevieve, Mo. Many of the fragments recovered at Cicott's location still were covered with a coat of whitewash. Taken in conjunction with the ethnohistoric accounts, this limestone foundation and the associated pierrotage may be seen to represent the remains of either a posts-on-sill or piece surpiece structure, both of which could have been set on a stone foundation.

This structure, of which these artifacts and features were the physical remains, was the product of a conscious decision by Zachariah Cicott. It was the most outwardly visible manifestation of both the personal and the ethnic identities which he chose to display to the world.

By the time of Cicott's birth, the French colonial experience in North America rapidly was drawing to a close. Detroit, the French entrepôt, or warehouse, for the southern Great Lakes region, had been an official British possession for 13 years. Nevertheless, the French of North America retained a separate sense of being, an ethnic identity. The personal choices made by Zachariah Cicott, such as his occupation, his selection of wives, and his style of house, — as reflected in the ethnohistoric and archaeological records — revealed that this ethnic identity persisted into the 19th century. Contrary to the statement in a book about Indiana history that "French civilization did not leave an abiding influence in the Indiana area" after 1763 (Barnhart and Riker, 1971:129), French men and women, with their distinctively French ways, did continue to play an influential role in both Indiana's development and settlement. And they did so for nearly a century after the Treaty of Paris had ended French control throughout the region.

REFERENCES

American State Papers (ASP)

1832 Public Lands. Vol. l. Gales and Seaton,

Washington.

1835 Indian Affairs. Vol. II. Gales and Seaton, Washington.

1860 Public Lands. Vol. VII. Gales and Seaton, Washington.

Au, Dennis M.

n.d. "French Architectural Influences in the Detroit

River Region." MSS. in the author's possession.

1991 a "Maps and Archaeology: The French Colonial Settlement Pattern in the River Raisin Community." Paper presented to the French Colonial Historical Society, The Newberry Library, May 10, 1991.

1991b "An Architectural Analysis: The Francois Vertefeulle House." MSS. in the author's possession.

Barnhart, John D. and Dorothy L. Riker

1971 Indiana to 1816: The Colonial Period.

Indiana Historical Bureau & Indiana Historical Society,

Indianapolis.

Barth, Fredrik

1969 Ethnic Groups and Boundries. Little,

Brown and Company, Boston. Burget, Frederick, trans.,

1974 St. Xavier Catholic Church, Vincennes, Indiana, Parish Records, 1749-1913. Vol. 3.

Deetz, James

1977 In Small Things Forgotten. Anchor

Press-Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y. Des Vos, George

1975 "Ethnic Pluralism: Conflict and Accommodation." In Ethnic Identity, ed. by George De Vos and Lola Romanucci-Ross, Mayfield Publishing Company, Palo Alto, Calif.

Dickason, Olive Patricia

1985 "From 'One Nation' in the Northeast to 'New

Nation' in the Northwest: A Look at the Emergence of the Metis." In

The New Peoples, ed. by Jacquiline Peterson and Jennifer S.H.

Brown, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Edmonds, John W.

1837 Report on the Claims of Creditors of the

Potawatomi Indians of the Wabash. Scatcherd and Adams, New York.

Ekberg, Carl J.

1985 Colonial Ste. Genevieve. The Patrice

Press, Gerald, Mo.

Goodspeed, Weston A.

1883 Counties of Warren, Benton, Jasper and

Newton, Indiana. F.A. Battey and Company. Chicago.

Hamlin, M. Carrie W.

1879 "Old French Traditions." Michigan Pioneer and

Historical Collections, IV, 70-78.

Hanes, Jacob, Sr.

1880 "Early Recollections of Independence, Warren

County, Indiana." Warren (Ind.) Republican, September 2,

1880.

Heckewelder, John

1888 "Narrative of John Heckewelder's Journey to the

Wabash in 1792," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography,

XII, 165-184.

Henry, John

1982 Zachariah Cicott." In The Independence

Sesquicentennial. Warren C. Historical Society, Williamsport,

Ind.

Illinois State Historical Society (ISHS)

1972 Pierre Menard Collection. Illinois State

Historical Society, Springfield.

Jones, James R., III, and Rob Mann

1992 "The Cicott Site: Evidence of Early 19th Century

Trade, Acculturation, Ethnicity on the Wabash River, Warren County,

Indiana." Tennessee Anthropologist. In press.

Knox County Court Files

1807 Box 16, File No. 1124.

Lajeunesse, Ernest J.

1960 The Windsor Border Region. University of

Toronto Press, Toronto.

Levering, Colonel John

n.d. "Copies of Notes Compiled by Col. John Levering

Before 1897." In Wetherwill File, Tippecanoe County Historical Society,

Lafayette, Ind.

Lux, Leonard

1949 "The Vincennes Donation Lands." Indiana

Historical Society Publications, Vol 15, No. 4, pp. 422-497.

Peterson, Jacquiline

1978 "Prelude to Red River: A Social Portrait of the

Great Lakes Metis." Ethnohistory, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 41-67.

Robertson, Nellie Armstrong and Dorothy Riker

1942 The John Tipton Papers. 3 vols. Indiana

Historical Bureau, Indianapolis.

Tanguay, L'Abbe Cyprien

1887 Dictionnaire Genealogique de Familles

Canadiennes. Vol. 3. Montreal.

Thornbrough, Gayle

1957 Outpost on the Wabash 1787-1791. Indiana

Historical Society, Indianapolis.

United States Congress

1826 "Abstract of Licences Granted to Citizens of the

United States to Trade with the Indians." House Doc. 118, 19th Cong.,

1st sess., serial 136.

1827 "Abstract of Licences Granted to Trade with Indians." House Doc. 140, Cong., 1st sess., serial 172.

1834 "Correspondence on the Subject of the Emigration of the Indians, 1831-1833." Senate Doc. 512 (yr. 5), 23rd Cong., 1st sess., serial 244-248.

Van Kirk, Sylvia

1980 Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society,

1670-1870. University Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Yount, H.N.

1908 "Reminiscences of Early Days in Warren County."

Warren. (Ind.) Review, September 10, 1908.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1991-1992/sec8.htm

Last Updated: 23-Mar-2011