CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Grand Teton National Park

|

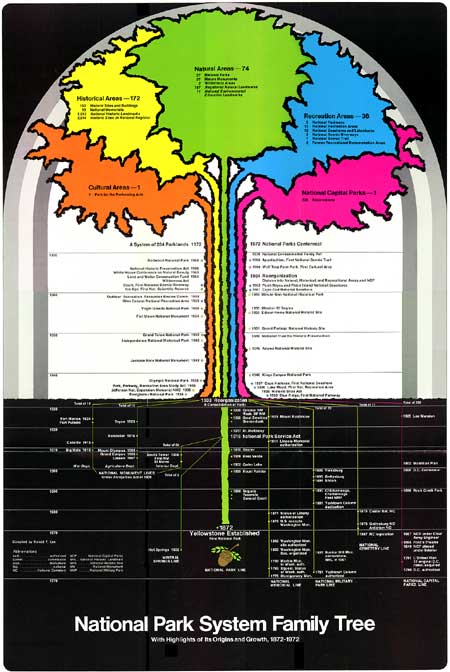

The following National Park System timeline has been extracted from Family Tree of the National Park System written by Ronald F. Lee to commemorate the centennial of the world's first national park — Yellowstone — in 1972. THE NATIONAL PARK LINE, 1872-1916

Yellowstone National Park, established March 1, 1872, marks the beginning of the National Park line and the center of gravity of the chart. A historian of National Park policies, John Ise, calls the Yellowstone Act "so dramatic a departure from the general public land policy of Congress, it seems almost a miracle." Although Yosemite State Park, created by Federal cession in 1864 to protect Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, was an important conservation milestone, Yellowstone was the first full and unfettered embodiment of the National Park idea—the world's first example of large-scale wilderness preservation for all the people. The United States has since exported the idea around the globe. The remarkable Yellowstone Act withdrew some two million acres of public land in Wyoming and Montana Territories from settlement, occupancy, or sale and dedicated it "as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." Furthermore, the law provided for preservation of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, and wonders within the park "in their natural condition." The twin purposes of preservation and use, so important and so susceptible to conflict, yet so eloquently reaffirmed by Congress when the National Park Service was established in 1916, were there from the beginning. Once invented—and Yellowstone National Park was an important social invention—the National Park idea was attacked by special interests, stoutly defended by friends in Congress, and refined and confirmed between 1872 and 1916. During this period fourteen more National Parks were created, most of them closely following the Yellowstone prototype. Their establishment extended the National Park concept throughout the West. Here are the successive areas:

Each of these National Parks has its own unique history. Collectively, this history is dotted with names important in conservation including, among many others, Frederick Law Olmsted; Cornelius Hedges and Nathaniel P. Langford; Professor F. V. Hayden; John Muir; William Gladstone Steel; George Bird Grinnell; J. Horace McFarland; successive Secretaries of the Interior from Carl Schurz to Franklin K. Lane; many members of Congress including Rep. John Fletcher Lacey of Iowa and Senator George G. Vest of Missouri; and successive Presidents including Ulysses S. Grant and Theodore Roosevelt. One milestone in this history is notable—the emergence of a distinction between National Parks and National Forests. Eighteen years elapsed after the Yellowstone Act before another scenic park was authorized, and then three — Sequoia, Yosemite, and General Grant — were created in the single year of 1890. Yosemite and General Grant were set aside as "reserved forest lands," but like Sequoia they were modeled after Yellowstone and named National Parks administratively by the Secretary of the Interior. The very next year, in the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, Congress separated the idea of forest conservation from the National Park idea. That act granted the President authority to create, by executive proclamation, permanent forest reserves on the public domain. Here is the fork in the road beyond which National Parks and National Forests proceeded by separate paths. Within sixteen years, Presidents Cleveland, McKinley, and particularly Theodore Roosevelt established 159 National Forests containing more than 150 million acres. By 1916 Presidents Taft and Wilson had added another 26 million acres. During this same period each new National Park had to be created by individual Act of Congress, usually after many years of work. Nevertheless, by 1916 eleven National Parks including such superlative areas as Mount Rainier, Crater Lake, Mesa Verde, Glacier, Rocky Mountain, and Hawaii, had been added to the original four and Mackinac abolished, bringing the total number to fourteen and the acreage to approximately 4,750,000. Establishment of these first National Parks reflected in part changing American attitudes toward nature. The old colonial and pioneering emphasis on rapid exploitation of seemingly inexhaustible resources was at last giving way, among some influential Americans, to an awakened awareness of the beauty and wonder of nature. In his book Nature and the American, published by the University of California Press in 1957, Dr. Hans Huth presents a fascinating account of the changing viewpoints toward nature in the United States which preceded and accompanied the rise of the conservation movement. America's leadership in National Parks is further explained by Dr. Roderick Nash in a stimulating article entitled "The American Invention of National Parks" published in the Fall 1970 issue of American Quarterly. In his view it resulted from four main factors—our unique experience with nature on the American continent, our democratic ideals, our vast public domain, and our affluent society. ... ... The issue of public good versus private gain, seldom as clearly drawn as at Yellowstone, is a recurring theme throughout the history of the National Park System. The whole modern movement for environmental conservation echoes with the same conflict. Yellowstone National Park stands as an enduring symbol of enlightened response to this issue, the kind of response even more urgently needed today if we are to succeed in preserving our environmental heritage. When establishment of the National Park Service finally came under consideration in Congress in 1916, J. Horace McFarland, President of the American Civic Association and an outstanding conservationist, expressed the views of many others in the following words, taken from his testimony before the House Committee on the Public Lands:

NATIONAL MONUMENT LINE I, 1906-1916 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR While the early National Parks were being created, a separate movement got underway to preserve the magnificent cliff dwellings, pueblo ruins, and early missions discovered by cowboys, army officers, ethnologists, and other explorers on the vast public lands of the Southwest from plunder and destruction by pot-hunters and vandals. The effort to secure protective legislation began early among historically minded scientists and civic leaders in Boston and spread to similar circles in Washington, New York, Denver, Santa Fe, and other centers during the 1880's and 1890's. Thus was born the National Monument idea. With important help from Rep. John Fletcher Lacey of Iowa and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, it was written into law in the Antiquities Act of 1906—with profound consequences for the National Park System. The National Monument idea extended the principle of the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 to antiquities and objects of scientific interest on the public domain. It authorized the President, in his discretion, "to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest" situated on lands owned or controlled by the United States to be National Monuments. The act also prohibited the excavation or appropriation of antiquities on Federal land without a permit. Between 1906 and 1970, under this authority, eleven Presidents proclaimed 87 National Monuments—36 historic and 51 scientific. Sixty-three are thriving National Monuments in the National Park System of 1972, eleven formed the basis for creation of nine National Parks, one became a National Battlefield, one a National Historic Site, one was added to a National Parkway, and ten small ones have been abolished. The Antiquities Act is therefore the original authority for one in every four units of the National Park System. These areas, counting their original boundaries and subsequent additions, contained approximately 12 million acres in 1970. The great majority of these acres, approximately 11,845,000, are in scientific monuments. Only 155,000 acres have been set aside for historic monuments. In addition to 87 National Monuments established under the Antiquities Act, between 1929 and 1969 28 others were authorized by individual Acts of Congress, generally on the pattern of those established by proclamation. Between 1906 and 1933 three Federal agencies, the Departments of Interior, Agriculture and War, initiated and administered separate groups of National Monuments. In the Family Tree, these form three National Monument lines, one for each department. Following is the first of these three lines, representing National Monuments established between 1906 and 1916 on lands administered by the Department of the Interior.

When President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act on June 8, 1906, Interior Department officials were well aware that the public domain and Indian lands contained remarkable natural wonders, great Indian ruins, and magnificent cliff dwellings that badly needed permanent protection. As early as 1889 Congress authorized the President to reserve the land on which the well known Casa Grande Ruin was situated from settlement or sale. In 1904, at the request of the General Land Office, Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett had made a comprehensive review of all the Indian antiquities located on Federal lands in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. After consultations with many other scientists, particularly those in the Bureau of American Ethnology, he had recommended specific sites for preservation. Hewett's review did not extend to public lands outside the Southwest, however, and no systematic survey had been made by anyone on any public lands to identify natural wonders that should be made National Monuments. The Antiquities Act made no provision for surveys. The Interior Department was therefore forced to rely largely for National Monument proposals upon an improvised combination of sources—recommendations from individual scientists or government officials exploring the West; accidental discoveries by cowboys or prospectors; offers by private citizens of donations of land suitable for preservation as monuments; projects conceived by local citizens and sponsored by members of Congress, some of which had been pending before Congress years before the Antiquities Act became law. On this basis, between 1906 and 1916 the Interior Department recommended and Presidents Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson proclaimed twenty National Monuments, eighteen situated on the public domain or Indian lands and two — Muir Woods and Sieur de Monts — on donated lands. Seven were historic and thirteen scientific, as follows: Devils Tower was the first National Monument, proclaimed by President Theodore Roosevelt on September 24, 1906. It was created to protect a well known Wyoming landmark, a 600-foot-high massive stone shaft sometimes visible in that almost cloudless region for nearly 100 miles and often used by Indians, explorers, and settlers as a guidepost. In December 1906, three more National Monuments were proclaimed — El Morro, New Mexico, famous for its prehistoric petroglyphs and hundreds of later inscriptions, including those of 17th century Spanish explorers and 19th century American emigrants and settlers; Montezuma Castle, Arizona, one of the best preserved cliff dwellings in the United States; and Petrified Forest, Arizona, well known for its extensive deposits of petrified wood, Indian ruins and petroglyphs. Of the twenty National Monuments that eventually composed this group, three later formed the nuclei for National Parks—Mukuntuweap for Zion, Sieur de Monts for Acadia, and Petrified Forest for the park of the same name. Three small areas were eventually abolished — Lewis and Clark Cavern, Shoshone Cavern, and Papago Saguaro. Within the decade of 1906-16 the National Monument idea became well established as a means of creating both historic and scientific parks. MINERAL SPRINGS LINE, 1832-1916 Mineral springs have been sought out for their medicinal properties since ancient times. Medicinal bathing reached its height of popularity in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries when tens of thousands of persons sought out such world famous spas as Bath, Aix-les-Bains, Aachen, Baden-Baden and Carlsbad. As mineral springs were discovered in the New World, they also came to be highly valued. By 1800, places like Saratoga Springs, New York, Berkeley Springs and White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, and French Lick, Indiana, were on their way to becoming popular American resorts. When significant mineral springs were found on western public lands it was natural for the Federal Government to become interested. In 1832 Hot Springs, Arkansas, was set aside as a Federal reservation to protect some 47 unusual hot springs that emerge through a fault at the base of a mountain. They were considered to have important medicinal properties significant to the nation. In 1870 the area was recognized by Congress as the Hot Springs Reservation and in 1921 it was made a National Park. Hot Springs is a health resort and spa rather than a scenic or wilderness area. Visitors have benefited from taking the waters at Hot Springs for more than a century and a half. In 1902 the Federal Government purchased 32 mineral springs near Sulphur, Oklahoma, from the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians. They were considered to have important health giving and invigorating properties. The Sulphur Springs Reservation was placed under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Interior who shortly acquired some additional land. In 1906 Congress passed legislation renaming the area Platt National Park in honor of Senator Orville Platt of Connecticut who had been prominent in Indian affairs and had died shortly before. When the National Park Service was established in 1916 the Hot Springs Reservation and Platt National Park were placed in the National Park System. They provide an interesting though somewhat tenuous link to the long history of spas and the ancient custom of "taking the waters." | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||