CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Great Basin National Park

|

National Parks and New World Idealism* by Arno B. Cammerer, Director, National Park Service This article first appeared in the Regional Review, Volume IV No. 6 - June, 1940

The national park idea originated in the new world. Many are familiar with the story of its origin, but for the benefit of those who are not I want to give a brief review. In 1870, an official party, known as the Washburn-Langford-Doane expedition, went into the little known headwaters of the Yellowstone River to make a reconnaissance of this reputedly wonderful region and to verify or correct the unbelievable stories that had been circulated for years about it. One evening after several weeks of exploration during which the territory had been thoroughly covered, the party was assembled around the campfire discussing the wonders of the region. Different members were laying claims to different regions of the Yellowstone and were making their plans for the development of its resources for their own private profit. One claimed a geyser basin, another claimed the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, another one claimed the Mammoth Hot Springs, and so on. Finally, one member of the party told the others that he thought they should look beyond their plans for private exploitation of the Yellowstone; he suggested that, instead of apportioning the region piecemeal for private benefit of the party members, the group should unite in an effort to have the area set aside for the benefit and enjoyment of all the people, to be protected for all time as a national park. The idea was accepted immediately and discussed long into the night. When their trip was over they dedicated themselves to the Yellowstone National Park idea with such effectiveness that the park was established by Act of Congress in 1872. Since this article was published,

the legendary campfire myth has been proven to be untrue.

Yellowstone was the first national park. Since then the idea has gone around the world. Soon after the establishment of the Yellowstone the demand for preservation and public use of other great scenic areas became widespread. By 1880, Senator Miller of California had introduced a bill to establish a national park in the southern Sierra to include Kings Canyon and the great sequoia forests. Ten years later small portions of that region were withdrawn from the possibility of private exploitation and set apart as the Sequoia and General Grant National Parks, and, in the same year, the Yosemite became a national park; but it was not for sixty years that Kings Canyon itself was given that status.

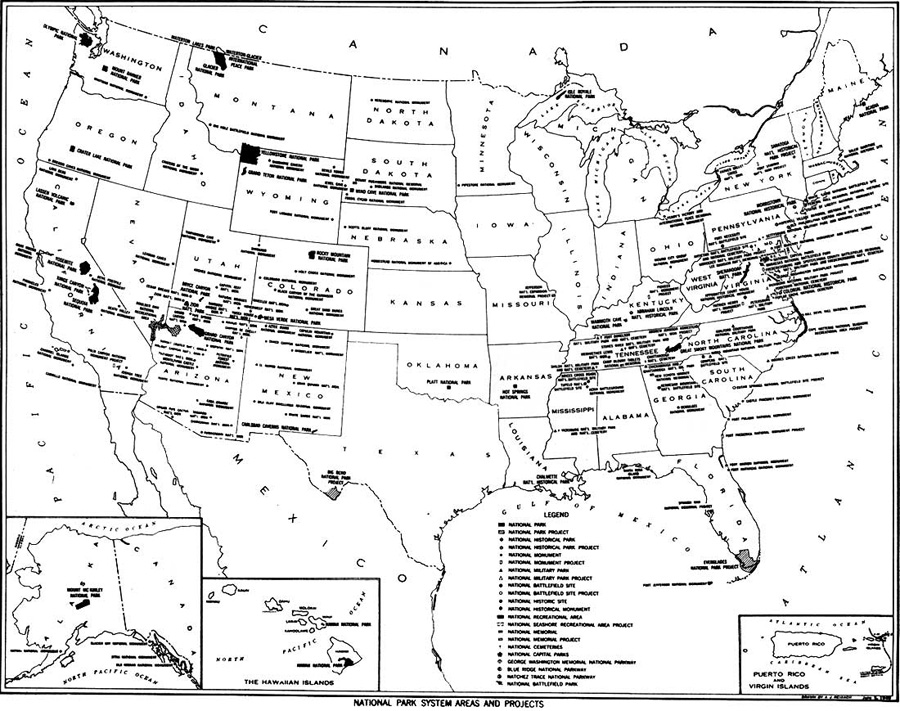

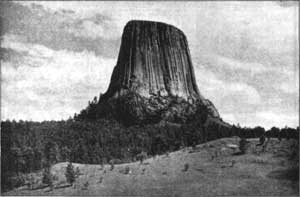

In 1906 a new step in the national park program came about through enactment of what is called the Antiquities Act. Congress then established the principle not only that all archeological material on the public lands is public property and cannot be removed without permission of the Government, but also that objects of historic, prehistoric, and scientific interest that are situated on the public lands may be set apart by proclamation of the President as national monuments to be conserved for public benefit. The first national monument established under the authority of the Antiquities Act was a famous western landmark, the Devils Tower in Wyoming, a spectacular volcanic core rising some 800 feet above the surrounding plains (See opposite page). Thus, the first national monument was an object of scientific interest. Several areas of archeological and biological interest soon were established as national monuments. These early monuments were important steps in developing the principle that objects and sites of prehistoric, historic and scientific interest, situated on the public lands, are important public resources worthy of preservation for public use. Congress established the National Park Service in 1916. Before that time there had been no bureau whose sole function it was to further the national park interests. Its purpose was defined:

At that time, the national park and monument system already included many different types of areas but no one agency was responsible for integration of the program. Some of the national monuments were administered by the Department of Agriculture. A large number of historic sites, parks, and memorials were administered by the War Department. In 1933, all of the national parks, monuments and related historic reservations administered by the Federal Government were made the responsibility of the National Park Service. A further growth in the national park program found expression in 1935 in the Historic Sites Act, in which Congress declared it "a national policy to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the people . . ." The act carried practical provisions empowering the Secretary of the Interior to cooperate with numerous types of agencies in protection and maintenance of outstanding historic sites, buildings, and objects.

A significant step toward a more coherent and integrated national recreational program was made in 1936 with passage of the Recreational Study Act, which authorizes the Secretary of the Interior, through the National Park Service and in cooperation with other federal agencies and with the several states, to conduct a study of the park, parkway and recreational-area programs of the country, in order to develop a coordinated national recreational program. The study is being conducted and many of the states already have transmitted reports. The national park system is composed today of 158 historic and natural areas, with a total of 21,515,000 acres. Regardless of the different types of parks and monuments in the national park system, there are certain general policies and practices that apply to all:

To meet the needs of park visitors, the Service has followed the general policy of providing a graded scale of accommodations, ranging from free campgrounds, provided by the government, to cabins, lodges, and hotels provided by the park operators. The Service attempts to provide facilities that will meet the financial requirements of every visitor. Having presented this brief review of the origin and growth of the national park system, I should like to discuss it as a form of land use in a general conservation program. Parks are an expression of maturity and restraint. They are an indication that people have begun to look outward and to see with perspective. With that perspective, it is seen that in our struggle for existence we can afford to preserve some of the native beauty of our land and to use it. The park concept is clearly the product of a balanced mind -- a mind that sees in a waterfall something more than potential horsepower, that sees in a giant forest something more than lumber, or that sees in a flowering mountain meadow something more than a sheep pasture, and, having seen, does not desire to exploit it for private gain. The national park idea is a consistent part of New World Idealism. Its development need not be limited except by our vision and our generosity. If we are far-seeing enough, park benefits can become an international heritage of the Americas. The native beauty of the land and the homespun cultural fabrics of each different country can become common heritage. The nature reservations and historic shrines of all the American countries can be united, not only by international parkways and peace parks, but likewise by the international language of the park idea, until there is a Pan-American Park System covering the continents from southern Chile and Argentina to Alaska and Canada.

Nature has given us the snowclad cordilleras reaching from Mount McKinley to Nahuel Huapi, the white line of breakers that rims the Americas, clean rivers, forests and plains teeming with wildlife, the fertile soil, and other resources in great abundance. Over it all, and made of it, is the scenic mantle, the element of natural beauty, which was not recognized as being a resource by the pioneers but which has come to be recognized as one of the indispensable resources of our civilization. This scenic and recreational mantle of the Americas is wearing then; moths, fire and acids have eaten it full of holes and in many places it is little more than the tattered shreds of a shawl. We should be wise to protect and restore it. This resource is indispensable because it is the re-creative resource, and recreation is essential to life. The recreational resource is not something that stands apart from the other resources; it is composed of them and is usually the total of them all. When it is conserved and utilized properly, there is strong probability that all the component resources are treated properly. Likewise, when the component resources have been squandered, the recreational resource has vanished. Recreational utility is rightly becoming the criterion of good land management, and parks are strongly indicated as the apex of a national conservation program. Parks are not a type of scenery; they are a type of public reservation. That type of reservation could be applied to an acre of grassland in the plains as well as to an acre of mountain summit in the Andes or the Rockies. Park standards refer therefore, not to the kind of natural scenery that may be selected f or park status, but to the use that is made of it. Here in the United States there has been hair-splitting difference of opinion for many years over the question of park status for this mountain peak or that one, because some other one, already established as a national park, is a little higher or may be resembled superficially by the peak that is being recommended for park status. Impractical as such dialectic is, famous scenic areas have been opposed for national park status for years on that basis. If there were two Yellowstones, should we refuse to use one of them?

Park reservation is equally applicable to the lofty mountains, the great plains, the southern coastal forests, the deserts, or the seashore. No matter what type of physiography may be chosen, or what biologic, geologic, historic, or archeologic exhibit, the purposes are the same: the areas are set apart to be preserved and enjoyed without impairment. While the 158 reservations in the national park system are grouped into 11 descriptive categories---such as parks, monuments, historical parks, historic sites, battlefield parks, memorials, etc.---they are all the same type of reservation. Generically all are parks. When someone attempts to break through one of these reservations and exploit its resources for private gain, that is a threat to park standards and should be a matter of public concern. Such attempts usually are piecemeal, and each is made by its proponents to appear reasonably insignificant. But the parkman knows from hard experience that all such invasions are cumulative, and that the toxin, if permitted, will in time become lethal. In the national parks we are trying to preserve the land whole, not that human use of the areas should be subordinated to nature protection, and not that in the parks we think more of wildlife or other objects than of people. Parks are for the people to use and there is no other reason for their existence. But, if a car is to transport us, we must keep its mechanism in running order. If parks are to serve us we must protect their natural machinery. There is a keen analysis of the point in Grinnell's and Storer's Animal Life in the Yosemite in which they describe how a segment of nature works. "The White-headed Woodpecker," they point out, "is a species which does practically all of its foraging on trees which are living, gleaning from them a variety of bark-inhabiting insects. But the White-headed Woodpecker lacks an effective equipment for digging into hard wood. It must have dead and decaying tree trunks in which to excavate its nesting holes. If, by any means, the standing dead trees in the forests were all removed at one time, the White-headed Woodpecker could not continue to exist past the present generation, because no broods could be reared according to the inherent habits and structural limitations of the species. Within a woodpecker generation, the forests would be deprived of the beneficent presence of this bird. The same, we believe, is true of certain nuthatches and of the chickadees--industrious gleaners of insect life from living trees. They must have dead tree trunks in which to establish nesting and roosting places, safe for and accessible to birds of their limited powers of construction and defense . . . Dead trees are in many respects as useful in the plan of nature as living ones, and should be just as rigorously conserved."

The type of facts that Grinnell and Storer point out is no hindrance to park management and use. Recognizing these facts in our plans and developments, we can increase the utility of our parks, and if our feet are on the ground, we can develop almost any kind of park. To do so, however, our purposes must be clearly in mind. These statements seem obvious, but in fact they are not. There is frequent conflict between parkmen, one faction charging that the other would lock up the parks and keep people out of them, the other asserting that the first would make city playgrounds of all parks. Would not both factions be nearer the truth if they agreed that there is no conflict---that we should, so to speak, render to Caesar the things that are Caesar's and to God the things that are God's? That we should not try to treat Jones Beach as we would the back country of Yellowstone or make Yellowstone serve as Jones Beach? Countless thousands may play on the beach and the tide comes and washes their tracks away. Countless thousands trampling the roots and packing the soil around a giant Sequoia tree will kill the tree that they come to see. Both the wilderness park and the heavily used beach have their places, and there is no legitimate conflict between them. Management of any park must partake of common sense and good taste so that development will not defeat the purpose for which it was established and that purpose will not be confused with the purpose of some other park.

Park management is more, of course, than common sense and good taste. It is a profession and a career in actuality, and the time is ripe for its techniques to be professionalized academically. The breadth of its activities, its intense absorption with people and nature, its concern with the physical evidences of history and prehistory, their preservation and interpretation, the host of practical skills required in construction, operation and maintenance and the ever-guiding objective of preserving the best and making it available--all these make the park profession one of the most attractive and stimulating of all careers. How many parks can we afford? How many acres are required? When will the saturation point be reached? The answer to these questions is expected to be given in quantitative terms; but recreation cannot be measured quantitatively because it is a quality of living. Who can say when our living is good enough? Yet I have seen statements that the present acreage of parks is all that the country will ever need. The only honest answer to these questions is, I believe, that the struggle to improve our living is a never-ending one, and that so long as any cultural and recreative factor in our historical and natural resources is being needlessly destroyed it is a challenge. Park status in such cases may be a more useful and productive status than any other, and present indications are that we can afford to live more generously than we have realized.

G. A. Pearson, in the Journal of Forestry,1 says: "Foresters no longer believe that every acre of land that can be made to grow timber must be used for that purpose. One hundred million acres of productive and well located timberlands could be made to produce annual yields far exceeding present consumption in this country. Additional areas to the extent of perhaps 300 million acres might well be kept in some sort of forest in the interest of recreation and watershed protection, and to provide a reserve acreage for timber production." If lands are no longer good for one use, it seems only common sense that we put them to another use. If lands are no longer needed for growing timber, for instance, or for some other industrial purpose, and they are of outstanding scenic and recreational character, would it not be simple wisdom to reserve them for recreation? The answer would be in the affirmative more often if it were not that there is a widespread tendency to try to do too many things for too many people on every acre of public land. This policy is referred to as a multiple use. Under it we are told that the resources of a proposed park are so intertwined and are of such great importance that the only way the area can be properly managed is to use all the resources simultaneously and equally, and, that if this is done, the recreational resource will receive full consideration along with the rest. It is a Utopian theory. In the first place, it does not recognize the nature of the recreational resource which, as has been said already, consists of the other resources in combination. As much as you take from each of the component resources, by so much do you take from it. As numerous writers have pointed out, this system of management, failing to recognize the dominant resource of a given area, detracts from its value by giving equal place to subordinate resources. This is apt to be little more than multiple abuse.

Of what virtue is it to advocate multiple use of a watershed that is worth a thousand dollars an acre for water catchment purposes? By the same token, of what virtue is it to advocate multiple use of an irreplaceable scenic resource that is of public inspirational value? To do so is to try to be all things to all people. It is to reduce land planning to local political pulling and hauling. It is the absence of planning. It would not be worth recognizing except that it is so widely accepted that it has become one of the greatest obstacles to sound land classification. Multiple use is a common, and often a good, feature of land management. As it is commonly accepted, however, it means the specific brand of land management that I have described, which sets multiplicity as its objective and permits a mediocre rating of every resource in a given area. Mr. Pearson, in the article already mentioned says:

Siegfried von Ciriacy-Wantrup, writing in the same journal, said:

Nobody could have any quarrel with multiple use as a descriptive term, provided it is only an incidental aspect of optimum use. A national park, for instance, which the multiple use exponents usually refer to as a single use form of land management, actually may provide several uses. It may provide vital watershed protection; serve as a wildlife sanctuary, as a natural and historic museum and place of public education; it may serve as a source of employment for local labor and a market for local products; increase the value of adjacent and tributary property, and, at the same time, serve as a stimulus to national and international travel, which in turn stimulates a host of other industries. All these are incidental to the dominant use of the land for recreation. In such case, the optimum use of the land includes several uses, but multiplicity is not the objective: it is an incidental, and even accidental, aspect. I sincerely believe that the exponents of multiple use really have optimum use in mind, and that they have no thought but that the natural resources should be appraised with intelligent selectivity. If that is the case, then we should recognize it by all means and admit that we do not hold multiple use either as a formula of land management or as an objective. Such action would revolutionize public land management. It would lead to the classification of lands according to their best uses. It would mean, for example, as Pearson says, that "Livestock production like timber production would profit immensely, if instead of trying to utilize all lands regardless of quality, the range industry were concentrated on lands really suited to it by climate, soil,and water facilities." It would mean that a national conservation program, insofar as the public lands are concerned, would be rational and flexible and that recreational lands would be classified as recreational lands rather than as forest or range or some other category for which they are largely useless. It would mean, in time, that lands classified according to their dominant use would be managed by agencies especially skilled in providing those uses, and that incidental uses would be permitted in accordance with their relative importance. In such a conservation program there might be more parks or there might not be, depending upon the classification of the resources. It might be found that recreational areas, so classified for their dominant use but subject to certain subordinate uses, would be a useful complement to the park systems. Such areas would be more apt to retain their distinguishing characteristics, and to render their maximum usefulness, if they were so recognized, but parks would remain the apex of the conservation program because they are the irreducible treasures. * From an address given May 13, 1940, before the Eighth American Scientific Congress, Washington, D. C. (1) "Forest Land Use." Vol. 38, No. 3, March 1940,

pp. 261-270.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||