CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

|

To celebrate the centennial of the National Park Service, each month we will reflect back on various aspects of the development of the National Park Service and the National Park System. This month we will take a brief look at NPS history. A Brief History of the National Park Service was written by James F. Kieley in 1940. This study gives an early-day view of the formative years of the National Park Service. In August we will present a more complete look back on NPS history. This month's reading list includes some early books published about the national parks, but also a collection of books showing the works of park photographers and artists who have captured a visual history of our national parks. A Brief History of the National Park Service

This is a brief statement of the history and organization of the National Park Service. It is the story of an organization whose traditions are rooted in the civic consciousness which gave birth to the national park idea; and of the men and women whose careers have been dedicated to that idea. It is offered to all who are engaged in this work, for the purpose of making them familiar with the origin, functions and objectives of the Service. Material contributed by various Branches and individuals is acknowledged with appreciation. This booklet was compiled and edited by James F. Kieley, associate recreational planner. The National Park Idea The idea of a "national park" must have jarred strangely the nineteenth century intellects upon which the words of a Montana lawyer fell as he spoke from the shadows of a campfire in the wilderness of the Yellowstone one autumn night 70 years ago. For Cornelius Hedges addressed a generation dedicated to the winning of the West. He spoke at a time when stout hearted pioneers had their faces determinedly set toward the distant Pacific as they steadily pushed the frontier of civilization and industrialization across prairie and mountain range to claim the land for a Nation between the coasts. His plan was presented to men cast of that die-men whose courage and enterprise characterized the era in which they lived. But Cornelius Hedges had looked deeply into American character and was not disappointed. He counted upon the altruism which marked that character, and planted in it the ideal which instantly took root and has since flowered as one of America's greatest treasures: the national park system. Thus was a new social concept born to a Nation itself reborn.

The man who broached the national park idea to those men of courageous spirit who comprised the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition for exploration of the Yellowstone was indeed the most courageous of all. This expedition of 1870 had set out at its own expense to investigate once and for all the incredible stories of natural wonders which had been coming out of the region for years, from the time the first scouts of fur trading companies blazed their trails across the fantastic wonderland. They found that all of it was true, and that the tallest yarns of the wildest spinners of tales (except perhaps the notorious Jim Bridger, who later simply embellished what nature had already provided) could hardly outstrip what the eye itself beheld. Here were the geysers shooting their columns of boiling water and steam into the sky; here were the hot pools, the mud volcanoes, and other strange phenomena. Here were the gigantic falls of the Yellowstone River in its gorgeously tinted canyon a thousand feet deep. Here were the forests and the abundance of wildlife in every form native to the region. Here, indeed, was a fairyland of unending wonders. As they sat around their campfire the night of September 19, 1870 near the juncture of the Firehole and Gibbon Rivers (now called Madison Junction), the members of the party quite naturally fell to discussing the commercial value of such wonders, and laying plans for dividing personal claims to the land among the personnel of the expedition. It was into this eager conversation that Hedges introduced his revolutionary idea. He suggested that rather than capitalize on their discoveries, the members of the expedition waive personal claims to the area and seek to have it set aside for all time as a reserve for the use and enjoyment of all the people. The instant approval which this idea received must have been gratifying to its author, for it was a superb expression of civic consciousness. As the explorers lay that night in the glow of dying embers, their minds were fired with a new purpose. In fact, some of them later admitted that prospects of the campaign for establishment of the Nation's first national park were so exciting that they found no sleep at all. This, then, was the birth of the national park idea. The idea became a reality, and the reality developed into a system which, through the years, has grown to embrace 21,011,778.58 acres of land and water including 25 national parks, 80 national monuments, and 45 national historical parks, national battlefields and other various classifications of areas. Please Note: The campfire myth was later proven to be untrue.

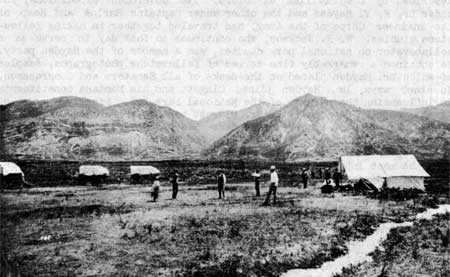

The advocates of the national park idea lost no time in following their plan through. First steps for carrying out the project to create Yellowstone National Park were taken at Helena, Montana, principally by Cornelius Hedges, Nathaniel P. Langford, and William H. Clagett. Fortunately for the plan, Clagett had just been elected delegate to Congress from Montana and was in a splendid position to advance the cause. In Washington he and Langford drew up the park bill which was introduced in the House of Representatives by the Montana delegate on December 18, 1871. During the preceding summer, the U. S. Geological Survey had changed its program of field work so as to give attention to the wonders described by the civilian explorers. Two Government expeditions, one under Dr. F. V. Hayden and the other under Captains Barlow and Heap of the Engineer Corps of the Army, had traveled together in making Yellowstone studies. W. H. Jackson, who continues to this day to serve as a collaborator on national park studies, was a member of the Hayden party. He obtained a remarkably fine series of Yellowstone photographs, samples of which Dr. Hayden placed on the desks of all Senators and Congressmen. In other ways, Dr. Hayden joined Clagett and his Montana constituents in influencing the passage of the National Park Act. Finally a copy of it was carried personally by Mr. Clagett to the Senate where it was introduced by Senator Pomeroy of Kansas. In response to a request from the House Committee on Public Lands for his opinion, the Secretary of the Interior endorsed the bill. The measure was put through after perhaps the most intensive canvass accorded any bill, in which all the members of Congress were personally visited and, with few exceptions, won over to its support. It was adopted by the House on January 30, 1872, passed by the Senate on February 27, and received the signature of President Grant on March 1. For the first time the Government had acted to conserve land for a new purpose. The term "conservation," so commonly applied to coal, iron, or other raw materials of industry, was now applied to mountains, lakes, canyons, forests and other great and unusual works of nature, and interpreted in terms of public recreation. Early Growth and Administration The United States had a system of national parks for many years before it had a National Park Service. Even before establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 as "a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people," the Government had shown some interest in public ownership of lands valuable from a social use standpoint. An act of Congress in 1852 established the Hot Springs Reservation in Arkansas (which became a national park in 1921), although this area was set aside not for park purposes, but because of the medicinal qualities believed to be possessed by its waters. It was not until 1890 that action was taken to create more national parks. That year saw establishment of Yosemite, General Grant, and Sequoia National Parks in California, and nine years later Mount Rainier National Park was set aside in Washington. Soon after the turn of the century the chain of national parks grew larger. Most important since the Yellowstone legislation was an act of Congress approved June 8, 1906, known as the Antiquities Act, which gave the President authority "to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments." In these early days the growing system of national parks and monuments was administered under no particular organization. National parks were administered by the Secretary of the Interior, but patrolled by soldiers detailed by the Secretary of War much in the manner of forts and garrisons. This, of course, was quite necessary, in the early days, for the protection of areas situated in the "wild and woolly" West. it is a fact that in this era highwaymen held up coaches and robbed visitors to Yellowstone National Park, and poachers operated within the park boundaries. The national monuments were administered in various ways. Under the Act of 1906 monuments of military significance were turned over to the Secretary of War, those within or adjacent to national forests were placed under the Department of Agriculture, and the rest—and greater number—were under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior. Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park, established in 1890 as the first Federal area of its type, was administered by the War Department. Under this disjointed method of operation, national parks and monuments continued to be added to the list until 1915 when its very deficiencies exposed the plan as unsatisfactory and inefficient. The various authorities in charge of the areas began to see the need for systematic administration which would provide for the adoption of definite policies and make possible proper and adequate planning, development, protection, and conservation in the public interest. National Park Service Created Realizing the specialized nature of national park work and the desirability of unifying the parks into one integrated system, Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane in 1915 induced the late Stephen T. Mather to accept appointment as his assistant to take charge of park matters. A keen lover of the out-of-doors, Mr. Mather accepted the appointment because he saw in it an opportunity to devote his energies to the furtherance of national parks. Under his efficient leadership the work was coordinated and expanded, and, on August 25, 1916, President Wilson signed a bill creating the National Park Service as a separate bureau of the Department of the Interior. The Service was organized in 1917. Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Representative William Kent of California sponsored the bills in Congress which resulted in establishment of the Service. Representative Kent's bill was passed by the House on July 1, 1916, and the Smoot bill was passed by the Senate as amended, August 5, 1916. (Mr. Kent had previously introduced three similar bills, and one had also been introduced in the House by Representative John E. Raker of California.) The Senate amendments were disagreed to by the House, and conferees were appointed to consider them. The conference report was made and agreed to in the Senate on August 15, and in the House on August 22. Efforts to obtain the necessary legislation for establishment of the Service had, in fact, been carried on for many years. President Taft sent a special message to Congress on February 2, 1912, in which he said: "I earnestly recommend the establishment of a Bureau of National Parks. Such legislation is essential to the proper management of those wondrous manifestations of nature, so startling and so beautiful that everyone recognizes the obligations of the Government to preserve them for the edification and recreation of the people." As the movement grew it involved the active support of many civic leaders interested in the conservation of lands for parks and recreation. Prominent among these was Dr. J. Horace McFarland of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who is now a member of the Board of Directors of the American Planning and Civic Association. As president for 20 years of the former American Civic Association, which he founded, Dr. McFarland focused public opinion upon the need for a Government bureau to take charge of national parks. The act creating the Service was largely the result of consultation between officials of the Department of the Interior and Dr. McFarland, Frederick Law Olmsted, and the late Henry A. Barker, representing the American Civic Association. Dr. McFarland's efforts began as early as 1908 when he addressed a conference of governors called by President Theodore Roosevelt to consider measures for conservation of the country's natural resources. He alone, among speakers at the conference, urged the conservation of scenery. Said he:

The American Civic Association continued its support of the national park movement, devoting its 1911 and 1912 annual meetings to that subject. When Mr. Lane became Secretary of the Interior in President Wilson's cabinet, Dr. McFarland called on him to urge the establishment of a bureau to administer the national parks. During the period preceding enactment of the bill to create the Service, Dr. McFarland, Mr. Olmsted and others carried on negotiations for keeping Congress informed, and worked untiringly through the American Civic Association for passage of the bill. Merged in 1935 with the National Conference on City Planning to form the American Planning and Civic Association, the organization founded by Dr. McFarland continues its active support of the national parks. Mr. Mather became the first director of the National Park Service, and put into his work all the energy and enthusiasm possible for a true lover of nature and one who appreciated the importance of proper control of park areas in order to permit use without damage or destruction. He even spent large sums from his personal fortune to acquire needed additions of land for parks, or to further necessary development operations. He was forced by ill health to tender his resignation on January 8, 1929.

Mr. Mather was succeeded by Horace M. Albright, who had come into the new Bureau as assistant to the Director. Mr. Albright had also served for nine and one-half years as superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, and thus was well grounded in the work when he assumed the directorship. Under his leadership the Service established a Branch of Research and Education and expanded its landscape architectural work. The national park system grew with the addition of three national parks and ten national cemeteries during his regime, and, under an Executive Order by the President, was given jurisdiction over park and monument areas formerly administered by the Departments of War and Agriculture. Mr. Albright resigned as director, effective August 9, 1933, to be come vice-president and general manager of the United States Potash Company, after 20 years of service in the Department of the Interior. He left behind him the most advanced ideas and ideals in conservation of natural resources for recreation, and still maintains his interest in park work as president of the American Planning and Civic Association, and a director of the National Conference on State Parks. Arno B. Cammerer, the present director of the National Park Service, was appointed to succeed Mr. Albright. He also carried to the office a broad background in park work, having been acting director on many occasions. He entered the Federal Service in 1904 as an expert bookkeeper in the Treasury Department, and was promoted through numerous higher positions to that of private and confidential clerk to several assistant secretaries of the Treasury. In 1916 he was chosen assistant secretary to the National Commission of Fine Arts, serving at the same time as first secretary of the Public Buildings Commission of Congress. In that period he served in various confidential capacities with officers in charge of Public Buildings and Grounds in connection with the parkway system of Washington, the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway, and the construction of the Lincoln Memorial and various other monumental structures in the National Capital. Mr. Cammerer joined the National Park Service in 1919 when Mr. Albright resigned the assistant directorship to become superintendent of Yellowstone National Park. The present director was selected by Mr. Mather and Secretary Lane to succeed Mr. Albright as assistant director. Later, as the activities of the Service expanded, he was made associate director. Outstanding has been Director Cammerer's work in the interest of the eastern park projects, including the Great Smokies, Shenandoah, Mammoth Cave, and Isle Royale. He represented the Secretary of the Interior personally in negotiations between the Federal Government and the states and various organizations engaged in acquiring the lands necessary for the establishment of these parks, worked out the park boundaries with the various state commissions, and in other ways assisted in bringing the projects materially nearer consummation. From its beginning, the National Park Service has been as fortunate in the caliber of men attracted to its ranks as in the fidelity of the friends of national parks who worked for the establishment of the Service and have since supported its program. One of the most valuable men who entered the Service soon after its organization was Roger W. Toll, superintendent of three national parks, who met death in an unavoidable automobile accident in 1936. Mr. Toll's wide knowledge of and experience in mountaineering, engineering, and general park problems made him especially valuable to the Service in the study of areas proposed for national park status, and several months each year he represented the Director in the investigation of such areas. At the time of the accident which caused his death and the death of George M. Wright, chief of the Wildlife Division, Mr. Toll was serving with his companion as a member of a commission of six appointed by the Secretary of State, at the request of the Secretary of the Interior, and with the approval of the President, to meet a similar committee appointed by the Mexican Government, for the purpose of studying possibilities of international parks and wildlife refuges along the international boundary between the United States and Mexico. Mr. Wright, although only 32 years old, had also had a distinguished career in the Service. While studying forestry at the University of California, he accompanied Joseph S. Dixon, at that time economic mammalogist of the University, on an expedition to Mount McKinley, Alaska, where he discovered the nest of the surf bird. After graduation, he held positions as ranger and junior park naturalist in Yosemite National Park, and became chief of the Wildlife Division when it was established on May 3, 1933.

General Policies Various acts of Congress and regulations set up by the Department and the Service have, during the years, become resolved into general policies for the protection, conservation, and administration of the national park and monument system. These policies were best set forth by Louis C. Cramton, special attorney to the Secretary of the Interior, the results of whose studies were incorporated in the annual report of the Director to the Secretary for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1932. They are:

Extension of Duties Since its establishment as a bureau of the Department of the Interior for the care and administration of the national park system, the duties and responsibilities of the National Park Service have been steadily extended by acts of Congress and Executive Orders. One of the most important of these was President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order of June 10, 1933 which effected consolidation, two months later, of all Federal park activities under the Service. This Order provided: "All functions of administration of public buildings, reservations, national parks, national monuments and national cemeteries are consolidated in an Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations in the Department of the Interior, at the head of which shall be a Director of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations; except that where deemed desirable there may be excluded from this provision any public building or reservation which is chiefly employed as a facility in the work of a particular agency. This transfer and consolidation of functions shall include, among others, those of the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior, and the National Cemeteries and Parks of the War Department which are located within the continental limits of the United States. National cemeteries located in foreign countries shall be transferred to the Department of State, and those located in insular possessions under the jurisdiction of the War Department shall be administered by the Bureau of Insular Affairs of the War Department. "The functions of the following agencies are transferred to the Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations of the Department of the Interior, and the agencies are abolished: Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission "Expenditures by the Federal Government for the purposes of the Commission of Fine Arts, the George Rogers Clark Sesquicentennial Commission, and the Rushmore National Commission shall be administered by the Department of the Interior." National monuments formerly administered by the United States Forest Service were included in these transfers. Although this Order designated the Service as the Office of National Parks, Buildings and Reservations, the original name "National Park Service" was restored in recognition of its prestige in the field of conservation, in the Act making appropriations for the Department of the Interior for the 1935 fiscal year. This was accomplished through the interest of Senator Carl Hayden of Arizona, chairman of the Senate Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee, which had charge of the bill. In accordance with the President's Executive Order, the Service was charged with maintenance of most of the Federal buildings in the National Capital, with the exception of certain buildings such as the Capitol, the main Treasury Building, Library of Congress, Government Printing Office, Supreme Court Building, and the National Bureau of Standards building. The Service also maintained a few Federal buildings outside the District of Columbia. In order to fulfill these additional responsibilities, the Service separated the functions of the former Office of Public Buildings and Public Grounds into two distinct units, the Branch of Buildings Management and the office of National Capital Parks. The Branch of Buildings Management was coordinate with the other administrative branches of the Service, while National Capital Parks is a field unit comparable to the various national park units outside the District of Columbia. On July 1, 1939, the Branch of Buildings Management was discontinued when the Public Buildings Administration was established under the Federal Works Agency to handle the operation of buildings. Another important piece of legislation affecting the activities of the Service was the Act of Congress approved August 21, 1935, empowering the Secretary of the Interior, through the National Park Service, to conduct a Nation-wide survey of historic American sites, buildings, objects, and antiquities. This Act also made provisions for cooperative agreements with states and local and private agencies in the development and administration of historic areas of national interest, regardless of whether titles to the properties were vested in the United States. A discussion of progress in historical conservation achieved under the Historic Sites Act will be given later. Prior to passage of the Historic Sites Act of 1955, the Historic American Buildings Survey was initiated, in December 1953, as a Civil Works Administration project, under agreement between the Secretary of the Interior and the Civil Works Administrator. Later authorized by Congress, it has been conducted in cooperation with the American Institute of Architects and financed successively by FERA, WPA, and PWA funds. The Survey has resulted in the collection of exact graphic records of more than 5,000 antique buildings and other structures, important historically or architecturally. This material is being filed by special arrangement with the Library of Congress among the pictorial American archives of the Library. Extension of National Park Service activities into the field of cooperation with the states and local governments in the planning of recreational areas, facilities and programs was authorized by the Park, Parkway and Recreation Study Act approved June 25, 1956. Under this Act the Service is conducting the Park, Parkway and Recreational-Area Study (discussed in detail under the heading "State Cooperation"). So widespread have the activities of the Service become, particularly since cooperation with the states began under the CCC and emergency relief programs in 1933, that an administrative system of four regions has been established. Each region is in the charge of a Regional Director, as follows: Region I, Miner R. Tillotson, regional director, Richmond, Virginia; Region II, Thomas J. Allen, regional director, Omaha, Nebraska; Region III, John R. White, regional director, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Region IV, Frank A. Kittredge, regional director, San Francisco, California. One of the most important aspects of the extended activities of the Service is the fact that although the Service is working in new fields and with funds coming from several sources, its enlarged personnel is no less a part of the organization in the traditional sense. This realization on the part of later appointees comes with the knowledge that the Service is a permanent bureau of a regularly established Department of the Government, and that no matter what phase of the program the individual is working on, it is an integral part of the whole program of the National Park Service. Development of the Educational Program Although Congress authorized establishment of the first national park as a "pleasuring ground," growth of the system by the addition of many areas of truly outstanding importance as living laboratories of natural history made it obvious that the parks offered superb educational opportunities. It was logical, then, that a program of research and education should be developed along with a program of recreational use. The educational advantages of the parks were recognized early by individuals and university groups, and at the turn of the century teachers were leading classes into these reserves for field study. In 1917 Director Mather launched his plans for an educational program by appointing Robert Sterling Yard as chief of the educational division. Immediately the Service introduced educational material into its booklets of information on the parks. At the same time, individuals without the Service—notably John Muir of the Sierra Club, C. M. Goethe and Joseph Grinnell of California—were attracting interest in the educational opportunities of the parks and stimulating in many persons a desire to study the geologic and biologic features of these areas. A national park educational committee was organized by Dr. Charles D. Walcott of the Smithsonian Institution in June of 1918. About a year later this group, consisting of 75 university presidents and representatives of leading conservation organizations, merged into the National Parks Association, and Mr. Yard left the National Park Service to become associated with this new organization. It was at this time that the concept of nature guiding, developed in a world survey which brought the idea from Europe to America, was being well demonstrated in Yosemite, where Dr. Harold C. Bryant, educational director of the California Fish and Game Commission, was delivering a number of lectures, and where trips afield for nature study were offered. By 1920 Mr. Mather and certain of his friends had become so convinced of the effectiveness of this work that they supported it with private funds. In that year Dr. Bryant and Dr. Loye Holmes Miller offered guided field trips and gave lectures in Yosemite to lay the foundation for later work.

The naturalist staff was not represented in the Washington Office until the Branch of Research and Education was established in 1930. Following the resignation of Dr. Wallace W. Atwood, Jr., as assistant in charge of work relating to earth sciences, Earl A. Trager was appointed in March 1932, to take charge of this section of the work. The following year the Naturalist Division was organized with Mr. Trager as Chief. The Naturalist Division consists of a staff located in the Washington Office, in Regional Offices and in the parks and monuments. The duties of the staff are:

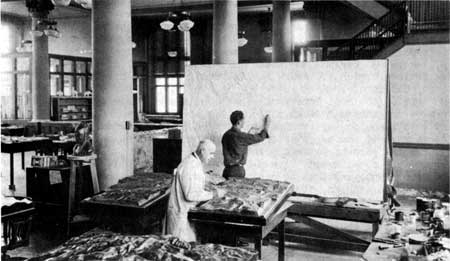

The staff in the Washington Office consists of executive and technical personnel; the staff in the field consists of technical personnel whose administrative duties are limited to those necessary to accomplish the field work program. The naturalists' program of conservation and interpretation involves work in the biological and geological fields. The technical assistance required in biology is supplied by the Wildlife Division. The technical assistance required in geology is furnished by geologists attached to the Naturalist Division. Coincident with the development of a "free nature guide service" in Yosemite, the Service began the interpretation of park phenomena through museum exhibits. Ansel F. Hall, previously in charge of information at Yosemite, was made park naturalist and developed a museum. In Yellowstone M. P. Skinner, under the direction of the Superintendent, organized a museum program. Nature guide service was established in other parks in the next few years, and in 1923 Director Mather appointed Mr. Hall as chief naturalist to extend the field of educational development to other parks. In the same year Dr. Carl P. Russell was appointed park naturalist in Yosemite and Mr. Hall devoted his efforts to the educational program in all the parks.

By this time it was seen that a definite plan of operation was needed, and Director Mather appointed Dr. Frank R. Oastler to investigate the educational work and, in collaboration with Chief Naturalist Hall, to draw up a general policy. An organization plan was prepared after Dr. Oastler had spent four and one-half months in the field in 1924. This outline defined the duties of the chief naturalist and the park naturalists, and advocated the development of an "educational working plan" for each park which would set forth the qualifications and training of the staff, an outline of each educational activity, plans of necessary buildings and equipment, and the required budget. Of special importance was the recommendation in this report that "each park should feature its own individual phenomena rather than try to cover the entire field of education." Another survey of educational opportunities of the parks was made in 1924 by the American Association of Museums, of which C. J. Hamlin was president, and definite plans looking toward the establishment of natural history museums in some of the larger parks were suggested. On the basis of this study the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial donated funds for construction of an adequate, fireproof museum building with necessary equipment and important accessories, in Yosemite. Even before the Yosemite museum installations had been opened to the public, demonstration of the effectiveness of the institution as headquarters for the educational staff and visiting scientists convinced leaders in the American Association of Museums that further effort should be made to establish a general program of museum work in national parks. Additional funds were obtained from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial and new museums were built in Grand Canyon and Yellowstone National Parks. Dr. Hermon C. Bumpus, who had guided the museum planning and construction in Yosemite, continued as the administrator representing the Association and Rockefeller interests, and Herbert Maier, now Associate Regional Director, Region IV, was architect and field superintendent on the construction projects. It was Dr. Bumpus who originated the "focal point museum" idea so well represented by the several small institutions in Yellowstone, each one concerned with a special aspect of the park story, and so located as to tell its story while its visitors were surrounded by and deeply interested in the significant exhibits of the out-of-doors. The trailside exhibits now commonly used in many national parks and first tried at Obsidian Cliff in Yellowstone were an out-growth of the focal point museum idea. When the museums of, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Yellowstone had demonstrated their value to visitors and staff alike, they were accepted somewhat as models for future work, and upon the strength of their success; the Service found it possible to obtain regular government appropriations with which to build more museums in national parks and monuments. When PWA funds became available, further impetus was given to the parks museum program and a Museum Division of the Service was established in 1935, embracing historic areas of the East as well as the scenic national parks. Today there are 68 national park and monument museums and two more are planned for the immediate future. Research and Information In 1925 the Secretary of the Interior approved Director Mather's plan for establishment of headquarters of the Educational Division at Berkeley, California, under Mr. Hall. Administration of the program was handled from that point until establishment of the Service's Branch of Research and Education under Dr. Bryant in Washington, D. C., on July 1, 1930. During this period administrative plans were developed for the educational activities of each park, in cooperation with the park superintendents and naturalists. Simultaneously, a plan of administration for the educational service as a whole was worked out, and its approval by the Director on June 4, 1929 formed the basis of operation and administration in the field. The principal study of educational program needs in the national park system was made by a committee appointed by the Secretary of the Interior in 1929, which operated with funds provided by the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial. Its personnel included Dr. John C. Merriam, chairman, and Drs. Hermon C. Bumpus, Harold C. Bryant, Vernon Kellogg, and Frank R. Oastler. These men made field trips in the summer of 1928 and reported many practical suggestions for development of the program. Acting on the recommendation of this committee, the Secretary of the Interior, in 1929, invited several eminent scientists and educators to serve on a National Park Service Educational Advisory Board. This group consisted of those already on the educational committee with the exception of Dr. Bryant, and in addition Drs. Clark Wissler, Wallace W. Atwood and Isiah Bowman. The committee on study of educational problems was also enlarged to include Dr. Atwood and Dr. Wissler. Further field investigations were conducted in 1929 and 1930 by the committee and its members rendered individual reports on the areas they visited. The committee submitted its final report to the Secretary of the Interior on November 27, 1929. In this report, it was recommended hat the position of educational director of the Service should be filled by a man "of the best scientific and educational qualifications," that headquarters of the educational division should be a part of the central organization in Washington, and that two assistants be appointed who, together with the head, should represent the subjects of geology, biology, anthropology, and history. With the establishment of the Branch of Research and Education in 1930, Dr. Harold C. Bryant, a biologist, was appointed assistant director in charge of this work. Dr. Wallace W. Atwood, Jr., was made assistant in charge of work relating to earth sciences, and a year later Verne E. Chatelain was appointed assistant in charge of historical and archeological developments. With these steps having been taken, the main work of the educational committee was completed, and the group was disbanded in 1931. Now called the Branch of Research and Information, this branch is charged with the task of interpreting to the public the natural phenomena within the national parks and monuments, conducting or sponsoring such research as is necessary to that program, and the protection and conservation of the natural resources therein. The planning and administration of the work of the Branch, which is comprised of three divisions, the Naturalist, the Wildlife (assigned to National Park Service duty from the Biological Survey), and the Museum Division, is under the direction of a Supervisor, Dr. Carl P. Russell, who was appointed to fill the vacancy caused by the transfer of Dr. Bryant to the Superintendency of Grand Canyon National Park in February 1939. Several main policies have been followed in the development of the educational program, and important among these are:

Wildlife The National Park Service is entrusted by the American people with protection, conservation, and proper management of characteristic portions of the country as it was seen by the early explorers. In fulfilling this stewardship, the Service is responsible for the protection of the animals which constitute the wildlife population of the parks. The wildlife management policies of the Service are based upon three points:

After wiping out vandalism and poaching in the parks, the Service realized that mere protection of the wildlife would not accomplish what was desired and necessary, and that an actual program of management was needed, to restore and perpetuate the fauna in its pristine state by combatting the harmful effects of human influence. The problem of wildlife management was aptly set forth in Fauna of the National Parks of the United States—No. 1, by George M. Wright, Joseph S. Dixon, and Ben H. Thompson: "The unique feature of the case is that perpetuation of natural conditions will have to be forever reconciled with the presence of large numbers of people on the scene, a seeming anomaly. A situation of parallel circumstances has never existed before." In considering its responsibility for the conservation of wildlife, the Service realized that mere protection was not enough. The need to supplement protection with constructive wildlife administration became evident with a steady increase of biological problems in many of the national parks and monuments. In 1929 a wildlife survey was undertaken in an effort to concentrate greater interest on the fundamental aspects of wildlife administration throughout the national park system. This survey involved a reconnaissance of the park system, to analyze and delineate the existing status of wildlife in the parks, to assist park superintendents in solving urgent biological problems, and to develop a well defined wildlife policy for the national park system. The results of this survey, together with proposed wildlife policies which have since been adopted by the Service, were published in the Fauna Series 1 and 2. For two years, from 1929 to 1931, this work was financed entirely by the late George Wright who personally paid the salaries of two men while contributing his own services. In 1931 and 1932 the Government began contributing toward the budget, although Mr. Wright continued his support of the work. In 1933 the Government took over the financing entirely. It was in that year that a Wildlife Division was formally established within the Branch of Research and Education for the purpose of directing all activities pertaining to conservation and management of park wildlife. Prior to 1934 the staff consisted of a chief, a field naturalist and a supervisor of fish resources. In 1934 this staff was increased with trained biologists employed under the Emergency Conservation Work program. Wildlife technicians are assigned to each regional office and are assisted by technicians of the associate, assistant, and junior grades. In November 1939, the Wildlife Division was transferred to the Biological Survey, which bureau immediately assigned all staff members to the same Park Service duties which they had been performing. The wildlife policies of the Service were recognized by the Biological Survey and subscribed to in the new inter-bureau relationships. They follow: Relative to areas and boundaries—

Relative to management—

Relative relations between animals and visitors—

Relative faunal investigations—

Plans and Design One of the chief responsibilities of the Service in its administration of the national park and monument system is to bring about a proper compromise between (1) preservation and protection of the landscape, and (2) developments for making park areas accessible and useful to the public. A delicate balance of conservation, calling for the exercise of sound judgment, is indicated in the correct adjustment of these seemingly opposing objectives. From the very beginning, the Service recognized this responsibility as a serious one to be discharged through careful professional planning. The first landscape architect was employed by the Service in 1918 more or less as a field adviser in the western parks. Thomas C. Vint, the present chief of planning, came into the Service in 1922, with headquarters in Yosemite National Park, California. In 1923 the office was moved to Los Angeles, and thence to San Francisco in 1927. The present Branch of Plans and Design was so designated in 1933. From 1927 until 1935 the Branch grew in personnel from three or four to a total of 120 employees, including architects and landscape architects. In 1936, when the Branch assumed additional responsibilities in connection with state park work, a total of 220 men in the professional classifications were employed. These, of course, did not include foremen assigned to CCC camps to do a considerable amount of work of the same nature. The main function of the Branch of Plans and Design is to serve as adviser to the Director and park superintendents on all matters of general policy and individual problems, covering physical improvements, development, preparation of plans and designs of an architectural or landscape architectural nature; and to design and prepare all architectural and landscape architectural plans and specifications for buildings constructed by the Government in the park and monument areas. The Branch prepares and keeps up to date a master plan showing the general scheme for physical development of each park and monument area, and supervises the preparation and revision of other master plans for areas being developed under the direction of the Service. It advises the Director on the location of parkways, and collaborates with the Public Roads Administration in the preparation of plans, construction and inspection of parkways, and the location, design and construction of major roads in park and monument areas, in accordance with the "Inter-bureau Agreement." It also collaborates with the Branch of Engineering in the construction of minor roads and trails in the areas of the system. Representing the Director, the Branch recommends approval or disapproval of landscape and architectural plans prepared by park operators and other concessionaire agencies, and consults and collaborates with them in the preparation of their plans. One of its chief functions is to maintain a construction program for each park, correlated with the master plan. It directs the activities of the Historic American Buildings Survey, supervising the preparation of drawings and supporting data, and keeping records of all other operations incidental to the successful operation of this program. The making of location surveys (of proposed parkways) is the responsibility of this Branch, and this involves the collection of data, maps and other information for proper presentation of reports and recommendations on parkways proposed. Another duty is the preparation of right-of-way plans for roads and parkways proposed or constructed by the Service. Engineering Making the areas of the national park and monument system available for public use has always presented problems in the proper design of structures and facilities. The earliest efforts in this direction demonstrated clearly the necessity for professional engineering services in planning developments in the park. The first real engineering undertaking in any park was, in fact, the famous Hayden Geological Survey Expedition into the Yellowstone in the '70's, made primarily for the purpose of collecting accurate geological and geographical data on the region. During the early years after establishment of Yellowstone National Park, no funds were available for development and there was little or no need for engineering services. When Congress finally appropriated money for road construction in the park in the '80's, engineering was placed under the U. S. Corps of Engineers. In 1883 Captain D. C. Kingman of the Corps became the first officer to be detailed for such work in Yellowstone, and thus was the first national park engineer. The first engineering structure in a national park was, undoubtedly, a log and timber bridge constructed over the Yellowstone River just below Tower Falls and not far from the present bridge across the stream. It was built by private interests who also constructed a road through the park to the Cooke City mining district just outside the park boundaries at the northeast corner. This structure was named Baronett Bridge and was built about 1870 or shortly thereafter. It became of historical interest when used by General O. O. Howard's command when he was pursuing the Nez Perce Indians under Chief Joseph through the park in 1877. Early engineering activities in the national parks consisted almost entirely of the construction of roads, bridges and trails. After the National Park Service was established, the needs for water and sewer systems, power plants, communication service, and other essentials were developed. The early operators, or concessionaires in the parks, were required to construct and maintain their own utilities in connection with the operation of hotels, camps and other types of accommodations. Road building was continued in Yellowstone and afterward in other national parks under the U. S. Corps of Engineers and immediate supervision of successive engineers until about 1917. Most prominent of the Army engineers of that era was General Hiram M. Chittenden who was assigned to Yellowstone National Park after the close of the Spanish-American War in 1899 and remained for a number of years. He accomplished the most in Yellowstone road building and also became the author of "The Yellowstone National Park," an historical and descriptive volume which is one of the best sources of authentic information on the history and phenomena of the Yellowstone. Through his efforts Congress appropriated upwards of a million dollars during the three years 1902 to 1905 for reconstruction of roads in Yellowstone to provide an excellent system of horse stage roads. A new road was built from the Canyon around to Mammoth Hot Springs by way of Dunraven Pass and Tower Falls to provide a loop making it unnecessary for tourists to travel any portion of the route a second time. This system of roads sufficed for horse stage travel and later for auto bus and automobile travel until the early '20's when small yearly appropriations became available for reconstructing some of the most dangerous sections and widening other sections to permit two-way travel.

As new areas were brought into the system from time to time in the '90's and after the turn of the century, the engineering activities were placed generally in the charge of the U. S. Corps of Engineers. There was, apparently, little correlation of methods and standards between the engineers in the various parks. After the National Park Service was created and took over administration of the system, the Corps of Engineers continued in charge of engineering work until April 1917 when George E. Goodwin was appointed the first civilian engineer of the Service, with the title of civil engineer. He made his first headquarters in Portland, Oregon, with an assistant in each of the larger parks. In 1921 Mr. Goodwin was made chief engineer, in general charge of all engineering in the national parks. After Congress passed the Roads and Trails Act of 1924 and appropriated funds for the building of roads, trails and bridges in national parks, the chief engineer's organization was considerably expanded in personnel for making surveys and plans, and for supervising construction activities. In July 1925, however, Mr. Goodwin retired from the Service and all major road building activities were turned over to the Bureau of Public Roads. Bert H. Burrell was appointed acting chief engineer pending this transfer and a decision on the future of the chief engineer's office. The Portland office was discontinued in the spring of 1926, some of the personnel being released and others being transferred to park engineering positions. The acting chief engineer, with a few employees, moved to Yellowstone to await developments. In the summer of 1927, Frank A. Kittredge was appointed chief engineer, and in September of that year the office and small organization were moved from Yellowstone to San Francisco to occupy joint space with the Landscape Division, since renamed the Branch of Plans and Design. The activities and personnel of the Branch of Engineering were rapidly increased to keep pace with the growing needs for engineering services in practically all the national parks and monuments. Except for four of the larger parks—Yellowstone, Glacier, Grand Canyon and Yosemite, where permanent park engineers were located—the chief engineer's organization had charge of the design and construction of all engineering activities except major roads. In the next few years they designed and constructed many important engineering structures such as the Kaibab Trail Bridge over the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park, the Carlsbad Caverns elevators, and the Yellowstone hydroelectric plant. The four permanent park engineers operated technically under the supervision of the chief engineer, and engineering personnel was assigned to all park areas as needed for making general and topographical surveys and for supervising all construction activities except major roads, and generally supervising the maintenance of park roads. Prior to 1930, the only national park in the east was Acadia, in Maine. Very little engineering service from the central organization was given this area, and such as was given was furnished by the chief engineer in San Francisco or the Bureau of Public Roads. In view of the prospect of establishment of additional eastern areas (with bills pending for establishment of George Washington's Birthplace National Monument, Colonial National Monument and the acquisition of land for an establishment of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Shenandoah National Park, and Mammoth Cave National Park, which were authorized in 1926) Oliver G. Taylor was transferred in May 1950 from Yosemite National Park, where he had been resident engineer for ten years, to a field position in the Washington office. Engineering work in eastern areas gradually increased until 1933 when there was a great increase in the number of eastern areas due to the transfer of public buildings and parks, national military parks and monuments and other areas from various Federal agencies to the National Park Service. This caused a tremendous increase in engineering responsibilities. These duties were first placed under Mr. Taylor as assistant chief engineer and later as deputy chief engineer, operating independently of the chief engineer's office in the west and reporting directly to the Director. The entire engineering organization of public buildings and parks came over to the National Park Service, but no engineering personnel was transferred with the military parks and monuments. It therefore became necessary to take on much additional engineering assistance. In August 1937, when the Service was reorganized on a regional basis, the office of the chief engineer was transferred from San Francisco to Washington where it assumed charge of all engineering work in the national park and monument system. At that time Mr. Kittredge was appointed regional director of Region IV, with headquarters in San Francisco, and Mr. Taylor was appointed chief engineer. Operations Functions of administration and personnel, budget, fiscal control, operators' accounts, and mails and files came into the picture at once, upon establishment of the National Park Service, and these matters were first placed immediately under the Director. Although the present Branch of Operations was not established until July 1, 1930, the various steps leading up to this began with the appointment of A. E. Demaray (now associate director) as senior administrative assistant on July 1, 1924. At that time Mr. Demaray was in charge of administrative work assigned by the Director, and supervised the editorial, mapping and drafting work, and the travel and informational work. On March 3, 1925 his title was changed to assistant in operations and public relations. On June 1, 1927 he was appointed as assistant to the director in charge of the preparation of estimates, administrative responsibility for road work in the park system, approval and control of expenditures, and approval of the rates of public operators. On October 11, 1929, Mr. Demaray was designated assistant director in charge of what was then called the Branch of Budget, Fiscal Control and Public Relations, and the Accounts Section was transferred from the Chief Clerk's Office to this new branch. On July 1, 1930 Mr. Demaray was appointed senior assistant director, and the name of the branch was changed to Branch of Operations, with responsibility for budget, accounting, and personnel work, embracing the following units: Division of Administration and Personnel, Division of Park Operators' Accounts, Division of Accounts, and Control Section. Hillory A. Tolson was appointed assistant director in October 1933 and placed in charge of the Branch of Operations. At present the Branch is composed of five divisions with the following functions: Budget and Accounts Division—Preparation of estimates of appropriations, including justifications and supporting data for use in defending them before the Budget Bureau and committees of Congress. Preparation of allotment advices pursuant to the provisions of appropriation acts or allocations making funds available. Supervision over preparation and compilation of financial and statistical data; accounting; auditing of expenditures; revision of the Accounting Manual; installation of approved systems of accounting to regulate fiscal operations; and receipt of revenues. Preparation of communications concerning accounting, budgeting, auditing and estimating of appropriations. Negotiation with representatives of General Accounting Office and other Governmental agencies concerning accounting and budget matters. Safety Division—Supervision over building fire protection and accident prevention programs. Preparation of fire protection and safety standards for use by those responsible for building and water system designs. Review of park operators' plans for fire protection and safety measures. Analysis of building fire and employees' injury reports. Training of park employees in fire hazard and accident hazard inspections. Preparation and dissemination of information regarding building fires and injuries and accident prevention and fire hazards. Chief of Division serves as Chairman of Safety Committee composed of representatives of the different Service branches. Public Utility Division—Furnishing of expert advice in the management and operation of public utility facilities (water, electricity, telephone, incineration, sewage) within the field areas administered by the Service. Conduct of rate analysis, valuations, and operating cost studies for determination of rate schedules for such public utility services. Preparation of plans, specifications, and estimates of new installations, extensions, improvements, and equipment purchases. Assistance to the Washington branches and field offices in connection with special utility problems. Personnel and Records Division—Supervision and coordination of all personnel matters for adherence to civil service rules and regulations and to the policies and procedure of the Department. Maintenance of appropriate personnel records. Compilation of information, statistics, and reports relating to personnel. Handling of receipt and dispatching of all mail. Maintenance of the general files. Preparation of instructions for guidance of field officers. Review of reports regarding irregularities by the Division of Investigations and Service auditors. Advice to Service officials concerning personnel problems, policies, and procedure. Control of expenditures from contingent and printing and binding appropriations. Negotiation with officials of the Department regarding personnel policies and procedure, establishment of positions, and purchase of office supplies and equipment. Park Operators Division—Supervision over field examinations of accounts and records of public service operators in areas administered by the Service. Prescribes bases on which amounts due the Government under franchise contracts shall be computed. Verification of correctness of amounts due under contracts and permits. Devises park operators' accounting requirements and procedure of reporting. Analysis of park operators' accounts and records for data to determine rates. Furnishing of data to officials to determine policies in exercising supervision and control over park operators' affairs. Law Supervision over all legal matters of the Service is the responsibility of the Office of Chief Counsel. This Office is an outgrowth of the position of Assistant Attorney in the Secretary's Office held by former Director Horace M. Albright before establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, when the national parks were administered directly by the Secretary. With the organization of the Service in 1917, Mr. Albright was appointed assistant director under former Director Stephen T. Mather. The position of assistant attorney formerly held by Mr. Albright was supplanted by that of "law clerk" authorized under the organic act of 1916. The position of "law clerk" advanced steadily in responsibility and volume of work as the Service grew from a small organization of some 25 employees in the Washington Office, to its present size. The designation of the position, accordingly, changed progressively to "assistant attorney," "legal officer," "assistant to the director," "assistant director," and finally to "chief counsel." All of these changes have taken place during the incumbency of the present Chief Counsel, George A. Moskey, who entered the Service in 1923. The Office of Chief Counsel was established October 24, 1938, when the former Branch of Land Acquisition and Regulation, headed by Mr. Moskey as assistant director, was abolished. This change, made at the time a number of revisions were effected in branch names and functions, was considered advisable in view of the fact that the Branch handled not only matters pertaining to land acquisition and regulation, but all legal matters for the Service. The Office is composed of a chief counsel and a force of assistants, principally attorneys. In addition, the Office also includes engineers, land appraisers and buyers, and specialized clerks. The functions of the Office of Chief Counsel are as follows: Supervision over all legal matters of the Service, rendition of administrative-legal advice, supervision over land acquisition, establishment of title to water rights, legislation affecting the national park system, and regulation of the various uses of these areas, and the acquisition of parkway rights-of-way. The Office renders assistance in formulating policies to govern various commercial activities in the national park system necessary for the accommodation and convenience of the visiting public. It acts as consultant to cooperating state and private agencies in technical matters relating to the establishment of new park or monument areas authorized by Congress. From this description, it will be seen that the functions of the Office of Chief Counsel are not limited to legal work. They are approximately 75 per cent administrative in nature, and include the responsibility of carrying on and supervising important programs of the Service's work, principally those with incidental legal aspects. For instance, a land purchase program is an administrative function. In the consummation of a purchase of land, however, legal questions are involved and must be dealt with and answered. The rendering of legal opinions and advising administrative officers on strictly legal phases of the Service work constitutes the other 25 per cent of the work of the Office. The duties and responsibilities of the Chief Counsel are thus distinguished from those of the Solicitor of the Department who is the chief legal officer of the Department, whose functions are essentially legal in nature, and to whom all legal questions requiring Departmental decision or approval are referred. With the great administrative responsibilities of the Office of Chief Counsel, it is not equipped with attorneys or personnel to undertake exhaustive research and investigations with a view to bringing out a legal issue. Its personnel is barely sufficient to carry on its programmed activities and the giving of legal guidance to administrative officers of the Service on current problems. Therefore, when situations confront the Service which require extended investigation or research as to facts before incidental legal questions are developed, field officers and administrative officers directly dealing with the problem are required to provide necessary reports from which the facts may be ascertained. Forestry The Act establishing the National Park Service makes specific provision for the control of attacks of forest insects and disease and otherwise conserving the scenery of the natural or historic objects in the parks and monuments. The protection of the park forests from destruction or serious damage resulting from fire, insects and disease, and from abuse through human use and occupancy has, therefore, been a primary function of the Service from its very inception. The protection activities are handled by the ranger force, which constitutes the basic protective organization of the parks and monuments. The importance of these responsibilities and the multiplicity of the technical problems involved created a need for a central office to assist and cooperate with the park and monument in the planning and administration of forest protection activities. The desirability of intensive study and scientific preparation of detailed forest protection plans was emphasized by a number of devastating forest fires within national parks during the exceptionally severe and disastrous fire season of 1926. Accordingly, the Forestry Division was created in 1927 under Chief Naturalist Ansel F. Hall, a graduate in forestry. To his duties in the development and administration of the educational service of the national parks and monuments was added the additional work of forest protection planning and administration, and his title was expanded to include that of Chief Forester. Headquarters for both the educational and forestry work were at the University of California, Berkeley, California. In July 1928 the position of Fire Control Expert was established in the Forestry Division at Berkeley to assist the Chief Forester in handling forestry and fire protection problems. John D. Coffman, a forester who had had many years of experience in forest protection and administration, was appointed to that position. In March 1933 the Fire Control Expert was called to Washington to assist the Director in the organization and administration of the Emergency Conservation Work program for the National Park Service, which so expanded and accelerated the conservation work of the Service that a Branch of Forestry, headed by Mr. Coffman as Chief Forester, was established in November 1933 with headquarters in Washington, D. C. With the regionalization of the Service in August 1937 a Regional Forester was appointed in each of the four regions to serve as technical adviser to the Regional Director in forestry matters and to head the forestry and fire protection work within the region. Each region also has one or more assistants to the Regional Forester to assist in the technical forestry work. The functions of the Branch of Forestry are:

The objectives of the Branch are:

Historic Conservation Historic conservation has been part of the conservation program of the Department of the Interior since 1906, and of the National Park Service since its establishment. The National Park Service Act itself named historic conservation as an important responsibility of the organization. Pursuant to the American Antiquities Act of 1906, the Department of the Interior, as early as 1916, had under its jurisdiction seven national monuments of historic and archeologic interest, as well as Mesa Verde National Park, which possesses the best preserved cliff dwellings in the United States. These areas were placed under the National Park Service on its establishment and formed the nucleus of its system of historic sites. In the period between 1916 and 1931, the number of historic and archeologic areas administered by the Service steadily increased, and by the latter year totaled 19, among which were such important areas as George Washington Birthplace National Monument and Colonial National Monument (now a national historical park), commemorating the establishment of Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in the United States, and the decisive American victory at Yorktown over Lord Cornwallis in 1781. Under the personal guidance of Mr. Albright, a program was evolved and a definite basis was laid for historical development. The growing importance of historic areas in the system of national parks and monuments, and the wide variety of questions new to the Service that these areas presented, led, in 1931, to the creation of an historical division in the Branch of Research and Education to study problems relating to historic conservation. Verne E. Chatelain was appointed head of this division and under his supervision significant progress was made in formulating policies and methods of procedure. The necessity for specialized study of historical problems was greatly emphasized two years later when, by Executive Order, the 59 historic and archeologic areas administered by the War Department and the Department of Agriculture were transferred to the Department of the Interior. Included in the transferred areas were such outstanding battlefields of the War Between the States as Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Through this development, the National Park Service became the recognized custodian of all legally designated historic and archeologic monuments of the Federal Government. As the historical and archeological program continued to broaden, it was recognized that it was desirable to extend the system to include most historic sites of national importance and to integrate the various pre-Columbian, colonial, military and other historically significant areas into a unified system which would tell the story of the United States from the earliest times. In order to facilitate the achievement of these objectives, the Branch of Historic Sites was established July 1, 1935, with Mr. Chatelain as acting head. The administration of scenic parks and historic sites, although involving many common problems, yet required such different methods of treatment that a separate branch to care for the broader planning and development of the historical program was essential. The functions of the branch were defined as the formulation of general policies, the supervision and coordination of the administrative policy and the interpretative and research programs of the different areas, and the Nation-wide survey of historic sites to determine which are of national importance. In November 1934, with a view to formulating a national policy for historic conservation, Secretary of the Interior Ickes appointed J. Thomas Schneider to survey the progress made in this field in the United States and to study the legislation of the leading foreign countries. It was largely on the basis of Mr. Schneider's recommendations that the Historic Sites Act of August 21, 1935 (49 Stat. 666), was framed. This Act, a landmark in historic conservation in the United States, greatly strengthened the legal foundation of the work of the Federal Government in this field. It declared as a national policy the preservation of historic American sites, buildings, objects and antiquities of national significance for the benefit and inspiration of the people, and empowered the Secretary of the Interior, through the National Park Service, to effectuate this policy. The Act authorized a survey of historic and archeologic sites to determine which possessed exceptional value historically, and empowered the Secretary to make cooperative agreements with states and other political units, and with associations and individuals to preserve, maintain, or operate a historic site for public use, even though title to the property did not rest in the United States.

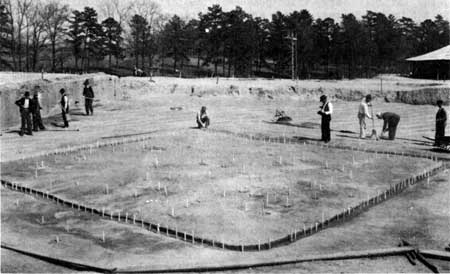

For the guidance of the Secretary and the National Park Service in carrying out this work, the Historic Sites Act created an Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments, which from the very beginning has been composed of eminent authorities in the fields of history, archeology, architecture, and human geography, such as Dr. Herbert E. Bolton, Dr. Waldo G. Leland, Dr. Clark Wissler, Mr. Frank M. Setzler, Dr. Fiske Kimball, and Dr. Hermon C. Bumpus. Since the Historic Sites Act provided for a large measure of inter-bureau and inter-departmental cooperation, as well as for outside assistance, the National Park Service has taken advantage of this fact to obtain technical advice from a variety of organizations and institutions. Many invaluable benefits have been derived from the advice and assistance of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives, the Library of Congress and the staffs of numerous university departments of history and archeology. Through a constant interchange of ideas with these groups and with the assistance of its own Advisory Board, the National Park Service has developed a body of policies governing the survey, development and operation of historic sites, which constitutes the underlying basis for a national program of historical and archeological conservation. Mr. Chatelain, who had been an important factor in the passage of the Historic Sites Act, and who had been acting head of the Branch of Historic Sites since its establishment on July 1, 1935, resigned in September 1936 and was succeeded by Branch Spalding, superintendent of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefield Memorial National Military Park. Under Mr. Spalding, the architectural and archeological work of the Branch was broadened, and important steps were taken toward establishing a permanent organization. In May 1938, Ronald F. Lee was made head of the Branch. Under him, the technical services of the Branch have been greatly strengthened, notably in the field of archeology, and a system of cooperation was worked out with the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution and the National Archives whereby these institutions give technical advice to the National Park Service and assist in research problems. At present, of the 155 areas administered by the National Park Service, 90 are primarily of historic or archeological interest. Land Planning Ever since the national parks and monuments were brought under the administration of one agency there has been a steady demand for the addition of numerous areas of many types to the system. This demand results from an increased public consciousness of the need for preserving areas of outstanding scenic, scientific and recreational values. For more than a decade the investigation of proposed new areas was made by the Director or by officers of the Service designated by him, including field men. It finally became necessary and advisable to concentrate this work under one office, and in 1928 the Branch of Lands was established under the late Washington Bartlett Lewis as assistant director. Mr. Lewis had been superintendent of Yosemite National Park from 1916 to 1928. The Branch of Lands had charge of the investigation of proposed new parks, extensions to existing areas, land acquisition, and the drafting work. A reorganization of these activities brought about the establishment of the Branch of Planning in 1931. Conrad L. Wirth, who had been associated with the National Capital Park and Planning Commission in the acquisition of land for the park system of Washington, D. C., was named assistant director in charge of the new unit, which took over the functions of the former Branch of Lands with the exception of land acquisition, which was transferred to Office of Chief Counsel. Through several stages of growth, the Branch of Planning has been assigned additional functions during the years, and is now called the Branch of Recreation, Land Planning and State Cooperation. It has charge of the advance land planning of the national system, and to it are referred, for investigation and report, all proposals for additions or extensions to the system. In making these studies the Branch usually calls upon other branches of the Service to collaborate on wildlife, historical, forestry, or other phases of the investigations. As a basis for the selection of areas for addition to the national park system, studies are conducted in the recreational use of land primarily to determine their relative values from a national standpoint. This involves research, field investigations and the assembling and analysis of data regarding scenic or landscape values, physiography, vegetation, wildlife, history, archeology, and geology as factors in the outdoor recreational environment. On the basis of findings through these general preliminary studies, investigations, of specific areas are conducted by the Branch, or caused to be conducted by other branches. From the assembled data recommendations are made for areas to be established as national parks, international parks, national battlefield parks, national historical parks, national military parks, national monuments, national battlefield sites, national historic sites, national cemeteries, national memorials, national seashores, national parkways and extensive trail systems, and additions to or abandonment of such existing areas. Upon the approval of a specific recommendation, the necessary data are assembled, the plan of action is outlined and presented to the Office of Chief Counsel for the handling of the necessary legal procedure. When an area is authorized by Congress for addition to the system, negotiations are directed for the final adjustment of boundaries within the limits authorized, and cooperation is given to the Office of Chief Counsel in the acquisition of lands. All advance planning programs, master plans and development plans pertaining to the national park system are reviewed for conformance with planning policies of the service. If such plans conform to Service policies they are concurred in by the Supervisor of Recreation and Land Planning (whose title was changed from assistant director) and referred to the Director for approval. It is also the duty of the Branch to study and negotiate proposed changes in nomenclature in the areas administered by the Service, in cooperation with the U. S. Board of Geographical Names. Information and data are assembled by the Branch concerning national parks of other countries for comparative study. This information is obtained direct from the foreign countries or by cooperation with the Department of State. State Cooperation When Federal cooperation was extended to the states in 1933 for park and recreation area development through CCC and relief labor and funds, the Branch was given charge of these activities. As Supervisor of Recreation and Land Planning, Mr. Wirth is the administrative officer of the Service immediately in charge of CCC and emergency relief-financed work in national parks and monuments, state, county and metropolitan parks and recreation areas. As a member of the Advisory Council of the CCC, he represents the entire Department of the Interior in its relations with the Civilian Conservation Corps. The Branch of Recreation, Land Planning and State Cooperation also has charge of the Park, Parkway and Recreational-Area Study.