CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument

|

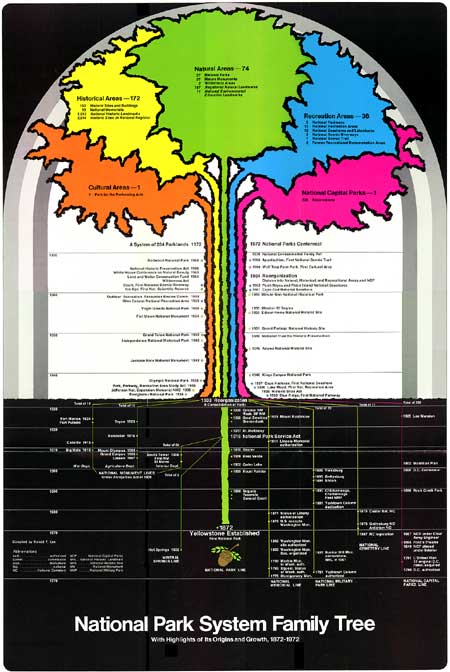

The following National Park System timeline has been extracted from Family Tree of the National Park System written by Ronald F. Lee to commemorate the centennial of the world's first national park — Yellowstone — in 1972. REORGANIZATION OF 1933

We come now to an event of profound significance for the future of the National Park System — the Reorganization of 1933. On June 10, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6166 which, in effect, consolidated all Federally owned National Parks and National Monuments, all National Military Parks, eleven National Cemeteries, all National Memorials, and National Capital Parks into one National Park System administered by the National Park Service. The story of how the great Reorganization of 1933 was finally brought about after 17 years of effort has been told in fascinating detail by Horace M. Albright in Origins of National Park Service Administration of Historic Sites, published by the Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 1971. The reorganization had three highly significant consequences: (1) it made the National Park Service the sole Federal agency responsible for all Federally owned public parks, monuments, and memorials; (2) it enlarged the National Park System idea to include at least four types of areas not clearly included in the System concept before 1933 — National Memorials, like the Washington Monument and the Statue of Liberty; National Military Parks, like Gettysburg and Antietam with their adjoining National Cemeteries; National Capital Parks, a great urban park system as old as the nation itself; and the first recreational area — George Washington Memorial Parkway; (3) the reorganization substantially increased and diversified the holdings in the System by adding 12 natural areas located in 9 western states and Alaska and 57 historical areas located in 17 predominantly eastern states and the District of Columbia. The number of historical areas in the System was thus quadrupled. The System became far more truly national than ever before. Each of the six groups of areas added to the System in the Reorganization of 1933 is represented by a separate line of the Family Tree. Each group added its own unique history and character to Service background and traditions. It is vital to understand these factors to comprehend the true nature of the National Park System. On the pages that follow these six lines are treated in this sequence:

National Capital Parks Line, 1790-1933 National Capital Parks is the oldest part of the National Park System, far older than Yellowstone, and traces its origin to the founding of the District of Columbia in 1790. In that year the President was authorized to appoint three Federal Commissioners to lay out a district ten miles square on the Potomac River as the permanent seat of the Federal Government. The commissioners were entrusted with control of all public lands within the District of Columbia, including parks. The original office established by the commissioners in 1791 was succeeded over the years by several offices with other names but similar functions, the legal succession continuing unbroken. As Cornelius W. Heine points out in his valuable work, A History of National Capital Parks (Washington: National Park Service, 1953) today's National Capital Parks office is a direct lineal descendant of the original office established by the first commissioners of the District of Columbia in 1791.

President Washington was intensely interested in the new seat of government. Early in 1791 he met with owners or proprietors of lands proposed for the new city and signed a purchase agreement which resulted in acquisition of 541 acres in seventeen different reservations. Lands within these original reservations became the foundation of National Capital Parks. Reservation No. 1, containing 83 acres, became the site of the Executive Mansion and grounds, Lafayette Square, and the President's Park south of the Mansion. Reservation No. 2, containing 227 acres, became the site of the Capitol and its grounds, and provided land for the eastern half of the Mall. Reservation No. 3, containing 27 acres, provided the site for the future Washington Monument. By 1898 a total of 301 park areas had been developed on the lands included in the 17 reservations purchased by President Washington in 1791. Washington engaged Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant to prepare a plan for the new capital city. The L'Enfant Plan proposed a city of beauty and magnificence, its central portion dominated by the triangle formed by the Capitol on Jenkin's Hill — "a pedestal waiting for a monument" — the Executive Mansion, and the Washington Monument, linked by the grand Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue. In addition to the Mall, L'Enfant envisaged a Congress Garden and a President's Park; fifteen squares, each embellished with statues, columns, or obelisks; five grand fountains; an equestrian statue of Washington; a Naval Column; and a zero milestone. From this plan are derived many of the important features of today's National Capital Parks. Rock Creek Park was authorized on September 27, 1890, two days after Sequoia and three days before Yosemite. Congress carried over some of the language of the Yellowstone Act into all three acts. Like Yellowstone, Rock Creek Park was "dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasure ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United States," where all timber, animals, and curiosities were to be retained "in their natural condition, as nearly as possible." Though not a National Park, Rock Creek Park is today one of the major urban parks in the United States. The District of Columbia celebrated its centennial as the National Capital in 1900. Unfortunately, important elements of L'Enfant's plan had been neglected over the years while unsightly developments intruded on open spaces, the most conspicuous being no less than a railroad station on the Mall. As a consequence of the Centennial, Senator James McMillan of Michigan led a movement to correct past mistakes and make a new plan for the entire District of Columbia park system. Four eminent experts were invited to prepare the plan — Daniel H. Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Charles McKim, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The result was the famous McMillan Plan for The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia published in 1902. This great document, a landmark in city planning in the United States, rescued and reestablished the main features of the L'Enfant Plan and added major new features, including an extension of the Mall westward, creation of East and West Potomac Parks, and provision of sites for the future Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials. It gave impetus to construction of the Arlington Memorial Bridge and acquisition of new park areas. Modern Washington, D.C., one of the most beautiful capitals in the world, is based on the L'Enfant and McMillan Plans. In 1916, when establishment of the National Park Service was under consideration in Congress, J. Horace McFarland cited the beauty of the National Capital, "expressing the dignity of the Nation," as an example which helped to justify establishing a National Park Service and System. Space here permits mentioning only a few of the highlights of the rich history of National Capital Parks. The Washington Monument was dedicated in 1885, and the Lincoln Memorial authorized in 1911; Ford's Theatre was acquired by the government in 1866, the House Where Lincoln Died in 1896; and the Custis-Lee Mansion was authorized for restoration in 1925. In 1930 Congress authorized the George Washington Memorial Parkway, the oldest unit of today's System classified as a Recreational Area. These and other historic sites, buildings, and memorials constituted a major group of properties when National Capital Parks was added to the System in 1933. National Capital Parks marked the entrance of the National Park Service into the urban park field, a field in which the Service is today demonstrating national leadership through its Parks for All Seasons program, urban beautification, and ultimately a series of National Urban Recreation Areas in the major cities of the United States. The twenty-one National Memorials are an important segment of the National Park System for they include such world famous shrines as the Washington Monument, the Statue of Liberty, the Lincoln Memorial, and others added to the System in 1933 and since. These have a long background important to understanding the System. The Continental Congress authorized the first memorials in our history during the Revolutionary War, just as it also authorized other symbols of nationhood — the flag, coins, and medallions.

The first memorial was authorized by the Continental Congress on January 25, 1776, to honor General Richard Montgomery, killed during an assault on the heights of Quebec in the midst of a snowstorm on the night of December 31, 1775. Montgomery commanded New York troops sent a few months before on an expedition, which also included Benedict Arnold's forces, designed to win Canada to the Revolutionary cause. It failed before Quebec, and Montgomery, only 37 years old, became one of the first Revolutionary generals to lose his life on the field of battle. When word of his death reached Philadelphia, Congress voted 300 pounds for a monument to Montgomery's memory, and entrusted the fund to Benjamin Franklin, shortly due to leave for Paris, in order that one of the best French artists might be secured to create it. Franklin engaged the King's sculptor, Jean Jacques Caffieri, to design and make the monument. Upon completion, in 1778, it was shipped to America in eight boxes, arriving at Edenton, North Carolina, in the midst of the War, where it remained for several years. Although originally intended for Independence Hall, in 1784 Congress decided to place the memorial in New York. Four years later it was carefully installed under the direction of Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant beneath the portico of St. Paul's Chapel, architecturally one of the most important buildings in the City and the church where Washington worshipped regularly as our first President in 1789. The Montgomery Memorial is still there today, and although not a part of the National Park System, St. Paul's Chapel is now a National Historic Landmark. The Continental Congress climaxed its commemorative actions in August 1783 by resolving "that an equestrian statue of General Washington be erected where the residence of Congress shall be established." L'Enfant's Plan provided a prominent location for this statue on the Mall at the intersection point of lines drawn west from the Capitol and south from the President's House — later the site of the Washington Monument. Washington approved this site but concluded that the expense of the statue was then unwarranted. It was not erected during his lifetime, but many years later, on January 25, 1853, Congress recalled the authorization passed seventy years before and provided the funds. The equestrian statue of Washington was executed by Clark Mills, placed in Washington Circle on Pennsylvania Avenue, and dedicated in 1859. It is there today, a significant feature of National Capital Parks and the National Park System, possessing an ancient origin in the halls of the Continental Congress itself. The death of Washington on December 14, 1799, threw the nation into mourning. A few days later, Congress passed a resolution introduced by Representative John Marshall providing for a marble monument in the Capitol to commemorate the great events of Washington's military and political life. This monument was not executed as planned. When the centennial of Washington's birth came in 1832 with no satisfactory monument to his fame in the National Capital, George Watterston, Librarian of Congress, and other civic leaders organized the Washington Monument Society, to erect an appropriate monument from private subscriptions. John Marshall agreed to serve as honorary president. In 1848 Congress transferred a site on the Mall to the Society, and the cornerstone of the Washington Monument was laid on July 4. But progress was slow, and further impeded by the Civil War. When the nation's first centennial came around in 1876 with the Washington Monument only one-third completed, Congress passed legislation authorizing the transfer of the Monument and site to the United States for completion and subsequent maintenance as a National Memorial. The Washington Monument was dedicated on February 21, 1885. During the Centennial years the people of France offered the Statue of Liberty as a gift to the people of the United States — another great National Memorial. On March 3, 1877, the President approved a joint resolution of Congress authorizing him to accept the Statue, provide a suitable site in New York Harbor, and arrange for its preservation "as a monument of art and the continued good will of the great nation which aided us in our struggle for freedom." The Statue of Liberty was dedicated on October 28, 1886. Each of the other National Memorials has unique interest, too. The first of the many monuments that dot the circles, squares and triangles of National Capital Parks to be completed was the equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson, which occupies the center of Lafayette Square, opposite the White House. It was dedicated in January 1853. Over the years more than 75 other memorials and monuments have been erected in the parks of the National Capital, including the Grant Memorial on the Mall, authorized on February 23, 1901. The great Lincoln Memorial was authorized by Congress on February 9, 1911, to occupy a site on the extended Mall proposed as part of the McMillan Plan. One of the most beloved of all our National Memorials, it was dedicated on May 30, 1922. Six more national memorials were authorized before the reorganization of 1933 — the Cabrillo National Monument, California, really a memorial, proclaimed in 1913; Perry's Victory Memorial, Ohio, authorized in 1919; Arlington Memorial Bridge, Washington, D.C., in 1925; Wright Brothers National Memorial, North Carolina, originally the Kill Devil Hill Memorial, in 1927; Mt. Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota, in 1925; and the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial, Washington, D.C. in 1932. In 1933 these National Memorials were added to the National Park System and the National Memorial function assigned to the National Park Service, except Perry's Victory Memorial, which was administered by a commission until it was added to the System in 1936. Also, the fiscal functions of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission were assigned to the National Park Service in 1933 and the Memorial itself in 1938. The National Military Park line, including early battlefield monuments, has a long and little known history. Beginning in 1781 the form of battlefield commemoration evolved during a century and a half and culminated between 1890 and 1933 in development by the War Department of what was in effect a National Military Park System. In 1933, this system numbered twenty areas, of which eleven were National Military Parks and nine National Battlefield Sites. Scores more were under consideration in Congress just before these areas were transferred to the National Park System and the management of battlefields added to the duties of the National Park Service.

Inspired by news of the victory at Yorktown, which ended the American Revolution, the Continental Congress on October 29, 1781 authorized the first official on-site battlefield monument in our nation's history. It resolved:

Funds for the marble column were not immediately available in 1781, and Congress did not implement this resolution until very long afterward — the centennial of Yorktown in 1881. Then the Yorktown Column was raised, in exact conformance to the resolution of the Continental Congress, and is now an honored feature of Colonial National Historical Park. The battlefield monument idea was given its greatest impetus, however, in Boston in 1823 when Daniel Webster, Edward Everett, and other prominent citizens formed the Bunker Hill Battle Monument Association to save part of the historic field and erect on it a great commemorative monument. The cornerstone was laid on June 17, 1825, Daniel Webster delivering a moving oration before a large audience. The Bunker Hill Monument showed the nation how to crystallize commemorative sentiment and became the prototype for a long series of battlefield monuments erected in the United States throughout the ensuing century. During the Revolutionary Centennial years, 1876-83, Congress appropriated federal funds to match local funds for Revolutionary battle monuments, and through this means imposing monuments were erected at Bennington Battlefield, Vermont; Saratoga, Newburgh, and Oriskany, New York; Cowpens, South Carolina; Monmouth, New Jersey; and Groton, Connecticut. Of these, Cowpens is now a unit in the National Park System, and Bunker Hill, Bennington, Oriskany, and Monmouth are National Historic Landmarks. Legislation is pending before Congress to add Bunker Hill Monument to the National Park System. The Revolutionary tradition embodied in such monuments, shared in common by North and South, helped draw the two sections together after the Civil War. Troops from South Carolina and Virginia participated in the centennial observance of the Battle of Bunker Hill in Boston in 1875 — the first time Union and Confederate veterans publicly fraternized after the Civil War. It was a moving occasion, and the practice of reunions soon spread to Civil War battlefields, culminating in spectacular veteran's encampments at Gettysburg in 1888 and Chattanooga in 1895. Meanwhile, on April 30, 1864, in the midst of the Civil War, Pennsylvania chartered the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association to commemorate "the great deeds of valor . . . and the signal events which render these battlegrounds illustrious." This association was among the earliest historic preservation organizations in the country. By 1890 it had acquired several hundred acres of land on the battlefield including areas in the vicinity of Spangler's Spring, the Wheatfield, Little Round Top, and the Peach Orchard as well as the small white frame house General Meade had used as headquarters. By this time a preservation society had also begun work at Chickamauga and Chattanooga. In the summer of 1888 General H. V. Boynton of Ohio revisited these battlefields with his old commander, General Van Derveer. Riding over the fields near Chickamauga Creek the idea came to them that this battlefield should be "a Western Gettysburg—a Chickamauga memorial." In September 1889, Confederate veterans joined with Union veterans and local citizens, including Adolph S. Ochs, to form the Chickamauga Memorial Association. With interest and support from both North and South Congress decided to go beyond the former battlefield monument concept to authorize the first four National Military Parks — Chickamauga-Chattanooga in 1890, Shiloh in 1894, Gettysburg in 1895, and Vicksburg in 1899. These areas were not selected at random but constituted, almost from the beginning, a rational system, designed to preserve major battlefields for historical and professional study and as lasting memorials to the great armies of both sides. The field of Gettysburg memorialized the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia; Chickamauga honored the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of Tennessee; and Shiloh and Vicksburg honored the Union Army of the Tennessee and the Confederate armies that opposed it. The National Military Park concept contemplated that the Federal Government would acquire the land with appropriated funds and preserve the cultural features of each battlefield while States and regiments would provide the monuments, thus combining preservation and memorialization in one undertaking. Acquisition of land for Gettysburg National Military Park led to an important decision by the United States Supreme Court. The Gettysburg Electric Railway Company, formed early in the 1890's, soon acquired rights of way for one branch penetrating deep into the battlefield. Believing the railway would irreparably deface the area, the Gettysburg National Park Commission recommended condemnation proceedings which were brought by the Attorney General in 1894. The Company contested the court's award by claiming that preserving and marking lines of battle were not public uses justifying condemnation of private property by the United States. The case reached the Supreme Court. In 1896 Justice Rufus Wheeler Peckham handed down the court's unanimous decision which read in part as follows:

Although Antietam was marked, beginning in 1890, and Chalmette, Kennesaw Mountain, and Guilford Courthouse were added to Federal holdings before 1918, no other battlefield projects were authorized for a long time. But after the victorious conclusion of World War I, Congressional interest in establishing new National Military Parks and related projects revived sharply. In 1923 Congress established the American Battle Monuments Commission "to erect suitable memorials commemorating the services of the American soldier in Europe." Two years later Congress authorized restoration of Fort McHenry in Baltimore "as a national park and perpetual national memorial shrine as the birthplace of the immortal Star Spangled Banner." Finally, in 1926 Congress authorized the War Department to survey all the battlefields in the United States and prepare a preservation and commemoration plan. Largely as a result of this survey, some twelve National Military Parks and National Battlefield Sites were added to Federal holdings between 1926 and 1933, including Fort Necessity, opening battle of the French and Indian War; Cowpens, Moores Creek, and Kings Mountain, battlefields of the American Revolution; and Appomattox Court House, Brices Cross Roads, Fort Donelson, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County, Petersburg, Stones River, and Tupelo, battlefields of the Civil War. Numerous others were in the planning stage. The National Military Park System was approaching maturity under the War Department in 1933 when all these battlefields were transferred to the National Park Service to become a significant and unique element in the National Park System. Since 1933 the Service has added seven more battlefields to its holdings, the most recent being Wilson's Creek, Missouri, in 1964. Battlefield commemoration is still a continuing Federal function. The National Cemeteries in the National Park System are closely related to the National Military Parks, but also possess distinction in their own right. Gettysburg National Cemetery is one of the two most revered shrines of its kind in the United States, the other being Arlington. Some understanding of the circumstances that led to its establishment and that of other National Cemeteries during and after the Civil War is necessary to comprehend their place in today's National Park System. The battle of Gettysburg was scarcely over when Governor Andrew Y. Curtin hastened to the field to assist local residents in caring for the dead or dying. More than 6,000 soldiers had been killed in action, and among 21,000 wounded hundreds more died each day. Many of the dead were hastily interred in improvised graves on the battlefield. Curtin at once approved plans for a Soldier's National Cemetery, and requested Attorney David Wills of Gettysburg to purchase a plot in the name of Pennsylvania. Wills selected seventeen acres on the gentle northwest slope of Cemetery Hill for the burial ground and engaged William Saunders, eminent horticulturist, to lay out the grounds preparatory to re-interments. Fourteen northern states provided the necessary funds. Saunders planned Gettysburg National Cemetery as we know it today, enclosed by massive stone walls, the ample lawns framed by trees and shrubs, the grave sites laid out in a great semi-circle, state by state, around the site for a sculptured central feature, a proposed Soldier's National Monument. The over-all effect Saunders sought was one of "simple grandeur." The Soldier's National Cemetery, as it was then called, was dedicated by President Abraham Lincoln on November 19, 1863. The speaker's platform occupied the site set aside for the Soldier's National Monument, then awaiting future design. The immortal words of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address endowed this spot with profound historical and patriotic associations for the American people. Gettysburg National Cemetery became the honored property of the nation on May 1, 1872, now a century ago. The events that followed the battle of Gettysburg were paralleled on the other great battlefields of the Civil War, including Antietam, Chattanooga, Fort Donelson Fredericksburg, Petersburg, Shiloh, and Vicksburg. Congress recognized the importance of honoring and caring for the remains of the war dead by enacting general legislation in 1867 which provided the foundation for the extensive system of National Cemeteries subsequently developed by the War Department. Eleven of the National Cemeteries established under that authority were added to the National Park System in 1933, each of them enclosed with stone walls and carefully landscaped to achieve the kind of "simple grandeur" that characterized Gettysburg. In every case they adjoined National Military Parks which were added to the System at the same time. The National Cemeteries however, were the older reservations in every instance, and in several cases, such as Gettysburg, Antietam, and Fort Donelson, provided the nucleus for the battlefield park. The act of 1867 also provided authority for preserving an important battlefield of the Indian wars when, on January 29, 1879, the Secretary of War designated "The National Cemetery of Custer's Battlefield Reservation." The National Cemeteries constitute a small but unique part of the National Park System. The Antiquities Act of 1906 authorized the President to proclaim National Monuments not only on western public lands but on any lands owned or controlled by the United States. Between 1906 and 1933 successive Presidents proclaimed ten National Monuments on military reservations:

These ten National Monuments constituted a small and not very representative part of the rich historical resources situated within the historic military reservations of the United States. The first War Department National Monument, Big Hole Battlefield, Montana, was established in 1910 to preserve the site of a major battle fought in August 1877 between United States troops and Nez Perce Indians led by Chief Joseph. Cabrillo National Monument, on the great headland of Point Loma, California, provided the site for a memorial to Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, Portuguese navigator and explorer who passed this point during his discovery voyage for Spain in 1542 — the first explorer to visit the shores of present-day California and Oregon. Mound City, Ohio, was proclaimed in 1923 to preserve the site of 24 burial mounds of the prehistoric Hopewell Indians. The next five National Monuments — an impressive group — were established by President Calvin Coolidge in a single proclamation signed October 15, 1924. Fort Marion National Monument, later given its old Spanish name of Castillo de San Marcos, preserved an ancient Spanish fort in St. Augustine, Florida, the first permanent settlement by Europeans in the continental United States. A second monument protected Fort Matanzas, constructed by the Spanish in 1742 to help defend the southern approaches to St. Augustine. Fort Pulaski National Monument preserved a magnificent early 19th century brick fort, encircled by a moat, located at the mouth of the Savannah River in Georgia. Taken over by Confederate forces at the outbreak of the Civil War, it yielded under bombardment by Federal rifled cannon in 1862. Little Castle Pinckney in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, was also declared a National Monument but has since been abolished. Finally, the proclamation declared the Statue of Liberty on Bedloe's Island in the harbor of New York to be a National Monument. The last two War Department National Monuments, Meriwether Lewis and Father Millet Cross, were proclaimed in 1925; but the first was subsequently added to the Natchez Trace Parkway and the second abolished. Although the authority to proclaim National Monuments on military reservations is still valid in 1972, no others have been proclaimed for 47 years. Instead, after World War II, a number of historic but obsolete fortifications were declared surplus by the War Department and transferred to the National Park Service, the States, or other political subdivisions following Congressional authorization. Examples are Fort Sumter National Monument, South Carolina, now a unit of the National Park System, and Fort Wayne, Michigan, now the property of the city of Detroit. The National Monuments established on military reservations under the Antiquities Act were added to the National Park System in 1933. Between 1907 and 1933, six presidents proclaimed 21 National Monuments on National Forest lands administered by the Department of Agriculture:

The first two National Monuments in the Department of Agriculture line were Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone, created within Lassen Peak National Forest, California, on May 6, 1907, to preserve evidence of what was then the most recent volcanic activity in the United States south of Alaska. Nine years later these two monuments formed the nucleus for Lassen Volcanic National Park. Fourteen of the other Department of Agriculture National Monuments were also established to preserve "scientific objects" on federal lands, including some of superlative importance to the nation. Moved by disturbing reports of plans to build an electric railway along its rim, President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Grand Canyon National Monument on lands within the Grand Canyon National Forest, Arizona, on January 11, 1908. The reservation contained 818,560 acres, an unprecedented size for a National Monument, thirteen times larger than any previous one. Roosevelt's bold action was later sustained in the United States Supreme Court, providing an important precedent for other very large National Monuments, such as Katmai and Glacier Bay in Alaska and Death Valley in California, proclaimed by other Presidents in later years. Grand Canyon National Monument formed the nucleus in 1919 for Grand Canyon National Park. On March 2, 1909, two days before leaving office, Roosevelt proclaimed another large scientific area, Mount Olympus National Monument, from lands contained in Olympic National Forest, Washington. The monument, containing 615,000 acres, was established to protect the Olympic elk and important stands of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, Douglas-fir, and Alaska cedar and redcedar. It formed the nucleus for Olympic National Park in 1938. Twelve other scientific National Monuments on National Forest lands included Bryce Canyon, Utah, proclaimed in 1923 to protect exceptionally colorful and unusual erosional forms. It formed the nucleus for Bryce Canyon National Park. Four caves were also proclaimed National Monuments — Jewel Cave, South Dakota; Oregon Caves, Oregon; Lehman Caves, Nevada; and Timpanogos Cave, Utah. Other significant scientific monuments included Pinnacles and Devils Postpile, California; and Chiricahua, Saguaro, and Sunset Crater, Arizona. The first of only five historical National Monuments proclaimed on National Forest lands was Gila Cliff Dwellings, New Mexico, established in 1907. It was followed by Tonto and Walnut Canyon in Arizona, and then by Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico, established within the Santa Fe National Forest. Containing 29,661 acres, Bandelier was transferred to the National Park Service in 1932, a year ahead of the others, and is now the third largest archaeological monument in the National Park System. Although authority to proclaim National Monuments on National Forest lands is still valid, only two others have been proclaimed since the Reorganization of 1933 placed all National Monuments under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. The two are Cedar Breaks, Utah, proclaimed August 22, 1933, from lands within the Dixie National Forest; and Jackson Hole, Wyoming, proclaimed March 13, 1943, principally from lands within the Grand Teton National Forest. NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM AREAS BY CATEGORY FOLLOWING THE REORGANIZATION OF 1933 We have now completed descriptions of each of the six branch lines of the Family Tree which joined the main line of the National Park System in 1933. The far-reaching consequences of this consolidation which brought important and diverse areas into the System may be visualized from the following table: National Park System Areas by Category

Natural areas increased from 47 to 58, reflecting the transfer of 11 scientific National Monuments from the U.S. Forest Service to the National Park Service. Historical areas almost quadrupled in number, increasing from 20 to 77 and becoming unequivocally a major category in the System. The first unit ultimately to be classified as a Recreation Area was added to the System — the George Washington Memorial Parkway — marking the beginning of a completely new category of areas. Lastly, a magnificent urban park system was added — National Capital Parks, represented on our table as a single area but actually containing hundreds of individual parks destined by 1972 to number 720 separate reservations. The total number of areas in the System more than doubled, increasing from 67 to 137, widely distributed throughout the United States. Once the Reorganization was achieved, the Service faced the formidable task of assimilating these many diverse areas into the fabric of the existing National Park System. This undertaking brings us to the next segment of the Family Tree. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||