CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Point Reyes National Seashore

|

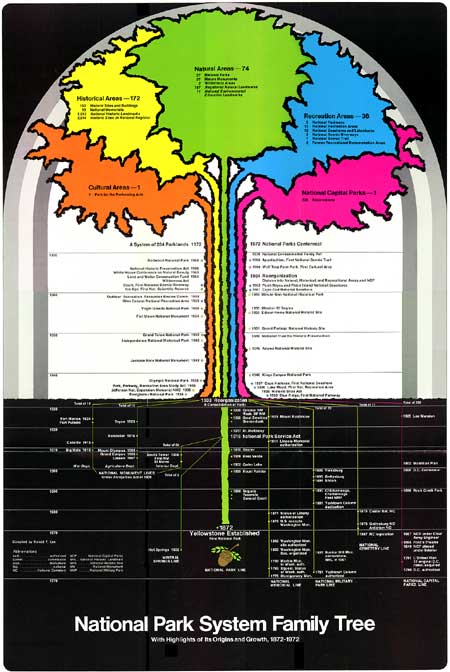

The following National Park System timeline has been extracted from Family Tree of the National Park System written by Ronald F. Lee to commemorate the centennial of the world's first national park — Yellowstone — in 1972. REORGANIZATION OF 1964

For purposes of clarity we have presented the Family Tree 1933-1964, as if it consisted of three branches — natural, historical, and recreation areas. Our presentation obscures the fact that in actual practice these three branches were not established until 1964. Before that date the Service undertook to assimilate these diverse areas into one largely undifferentiated System. That System was guided by a single code of administrative policies derived largely from National Park experience but—with the addition of policies on historic preservation—made equally applicable to all areas. On July 10, 1964, Secretary Stewart L. Udall signed a memorandum to the Director of the National Park Service instituting a new organizational framework for the National Park System. This new framework, based on recommendations made by Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., was a major step forward in the evolution of the System. The memorandum stated: "It is clear that the Congress had included within the growing System three different categories of areas — natural, historical and recreational. . . . A single broad management concept encompassing these three categories of areas within the System is inadequate either for their proper preservation or for realization of their full potential for public use as embodied in the expressions of Congressional policy. Each of these categories requires a separate management concept and a separate set of management principles coordinated to form one organic management plan for the entire System." The memorandum outlined the principles of resource management, resource use, and physical development that should characterize each category, and approved a new statement of long-range objectives. This landmark memorandum belongs in the select series of Secretarial statements, beginning with Franklin K. Lane's letter of May 13, 1918, to Stephen T. Mather, that have had great and lasting influence on the growth of the System. Years ago there were good reasons for an undifferentiated System. After the transfer of 57 historical areas in a single action in 1933, clearly the first Service task was to assimilate them. The administrative policies which obtained when those areas were under the jurisdiction of the War Department were incompatible with longstanding National Park Service policies in such fields as public information, interpretation, forestry, plans and design, and concessions. The Service started its task of assimilation by applying its own well-established park policies to the new additions as rapidly as possible. Service officials were also concerned that if the historical areas were set off by themselves, some dedicated nature preservationists would endeavor to separate them as a group from the System so that it might be made to consist solely of natural areas. Public efforts by some conservationists to achieve that objective may have justified their concern. In the background was the belief that retaining the historical areas as an integral part of the System would strengthen the hand of the Service in Congress because most historical areas were located in eastern Congressional districts with no other intimate ties to the Service. No doubt this was true. Unfortunately, this belief prompted some Service officials to value the historical areas as much for the support they brought to natural areas as for their intrinsic value as parts of our common national heritage. It took the Service more than thirty years after 1933 publicly to recognize the historical areas as a separate segment of the System with distinct roots and character of its own, yet interdependent with the other segments containing natural and recreational areas. This was one of the most important and timely insights of the Reorganization of 1964. Assimilation of recreation areas into the National Park System is a separate story. For a long time after its establishment in 1916, the Service opposed taking responsibility for any area whose primary justification was provision of active outdoor recreation for large numbers of people. It was thought that state parks, county and municipal parks, and other public reservations, not National Parks, should take care of most public recreation needs. Years ago there was justified concern that if the Service opened its arms to administer recreation facilities at Federal reservoirs, mass recreation and possibly artificial lakes might soon invade the National Parks as well, and such choice places as Yosemite Valley, Yellowstone Lake, and Mount Rainier might lose their superb natural qualities and become little more than playgrounds. Furthermore, the National Park Service did not have primary jurisdiction over lands in such recreation areas as Lake Mead, which was basically under the Bureau of Reclamation. Service responsibilities derived from a cooperative agreement. The consequence was that many conservationists and some officials opposed accepting National Recreation Areas as fully qualified units of the National Park System. The Act of August 8, 1953, defined the System in such a way as to leave them out:

The Reorganization of 1964 prepared the way for Congress to replace the 1953 definition of the National Park System with a revised concept. For the first time it clearly and unequivocally established recreation areas as one of the three segments of the National Park System. Furthermore, it had the tremendous merit of differentiating recreation areas from natural areas. By this means, some of the earlier concern that identical policies might govern both natural and recreation areas was dissipated. Important fruits of the Reorganization of 1964 were realized in 1968. In that year Director Hartzog issued three publications of fundamental importance to the future management of the National Park System: Administrative Policies for Natural Areas . . .; Administrative Policies for Historical Areas . . .; and Administrative Policies for Recreation Areas . . .. It had taken almost a century for the Service to fully articulate and distinguish the fundamental concepts contained in these publications. Although they had been implicit in the evolving history of the National Park System now they were made explicit. As we shall later see, in 1970 Congress adopted a new definition of the National Park System consistent with the Reorganization of 1964, and it is in effect today. |