CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area

|

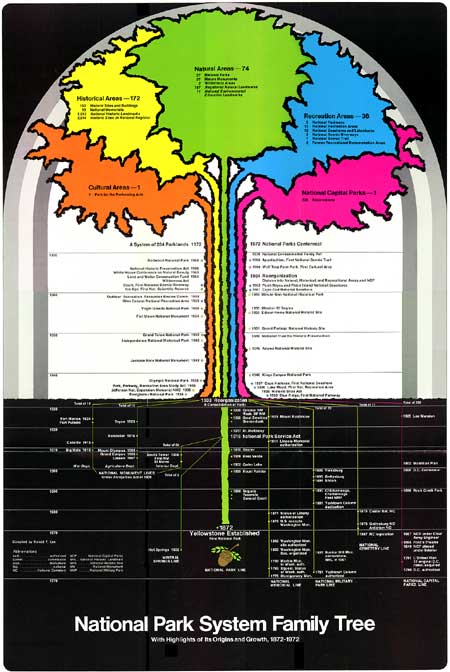

The following National Park System timeline has been extracted from Family Tree of the National Park System written by Ronald F. Lee to commemorate the centennial of the world's first national park — Yellowstone — in 1972. GROWTH OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM, 1964-1972

Between 1964 and 1972 the National Park System experienced unusual growth. Under the leadership of Director George B. Hartzog, Jr. and Secretaries of the Interior Stewart L. Udall, Walter J. Hickel, and Rogers C. B. Morton, 62 areas were authorized, added to the System, or given new status, in eight years. Of these 13 were natural areas, including five new National Parks; 29 were historical areas, including a series of historic sites and buildings honoring seven former Presidents of the United States; 20 were recreational areas, including eight National Seashores and Lakeshores, three National Scenic Riverways, and one National Scenic Trail; and one was a Cultural Area, an entirely new category in the System. This remarkable growth benefited much from groundwork laid during preceding years but it also derived substantial impetus from the "New Conservation," a term widely used to describe the drastically enlarged scope of the conservation movement which took shape during the 1960's. The New Conservation Although it had other roots, for present purposes the "New Conservation" may be considered as beginning with the 1962 report of the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission, establishment of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation the same year, and creation of the Land and Water Conservation Fund in 1964. This important Fund played a determining role in enlargement of the National Park System during this period. The movement had many other aspects too important and complex for extended discussion here. Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall articulated important aspects of the "New Conservation" in his book The Quiet Crisis and in his annual reports. Important developments affecting the System included passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964 and the beginnings of the National Wilderness Preservation System. In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson convoked the White House Conference on Natural Beauty, which gave new emphasis at the highest levels of government to the importance of aesthetic values, primarily natural but also cultural. In the ensuing years, under Mrs. Johnson's leadership, the natural beauty movement spread from Washington, D. C. — where important aspects were demonstrated in National Capital Parks for all the nation to see — to States and communities all over America. Historic preservation became part of the "New Conservation" with enactment of the highly important National Historic Preservation Act in 1966. Among other important steps he took to extend and deepen the "New Conservation," President Richard M. Nixon launched his Legacy of Parks program and proposed World Heritage Trust in 1971. Underlying all these widening concerns of the 1960's and early 1970's was a growing national conviction that partial conservation programs, however meritorious, were inadequate to meet modern problems. The fabric of life, it was finally realized, is seamless. This conviction grew as millions of Americans saw with their own eyes the steady spread of air and water pollution in their own neighborhoods to levels hazardous to life. The intolerable consequences of dramatic off-shore oil spills, deadening smog, filthy rivers, and diminishing open space were evident on every hand. Scientists announced that the very foundations of life on earth were in jeopardy because of the profound impact of modern technology on the total ecology of the globe. But among all the factors that forced Americans to turn their full attention to the life-giving qualities of their environment, none equalled the landing on the moon. The truth came as a revelation. Viewed from outer space, the planet earth is a small green orb in an apparently lifeless immensity and man's only home. The first comprehensive response to this revelation was Congressional passage of the National Environmental Policy Act signed by President Nixon on January 1, 1970. This legislation has been called by Senator Henry Jackson of Washington "the most important and far-reaching environmental and conservation measure ever acted upon by the Congress. . . ; The survival of man, in a world in which decency and dignity are possible, is the basic reason for bringing man's impact on his environment under informed and responsible control." The act established new national environmental goals for the United States and forged new administrative instruments for environmental conservation. Under its authority, during 1970, President Nixon created two major new agencies. One, the Council on Environmental Quality in the Executive Office of the President, monitors environmental conservation. The other, the Environmental Protection Agency, consolidates into one agency the major Federal programs dealing with air pollution, water pollution, solid waste disposal, pesticides, and environmental radiation. After these developments, the roles of the National Park System and Service in American life had to be viewed anew in the light of their relationship to the quality of our total environment. One specific response was development of a National Park Service program for environmental education beginning as early as 1968. The program was called NEED, or National Environmental Education Development, aimed especially at bringing school children to a critical awareness of their environment, but also directed to all park visitors. It included designation of Environmental Study Areas on National Park System lands to be used primarily by school children to help them understand their total environment, its many interdependent relationships, and their part in it. In 1971 a further program was adopted to confer national recognition on non-federal sites possessing outstanding quality for environmental education by designating them National Environmental Education Landmarks. Secretary of the Interior Rogers C. B. Morton designated the first eleven sites in 1971, situated in nine states and the District of Columbia. In a broad sense, all the interdependent and developing programs of the National Park Service are aimed at contributing to the formation of a new environmental ethic among the American people, "a foundation on which our citizens may renew and preserve the quality of our national life." The National Park System in all its unity and diversity came to be seen as an on-going expression of America's continuing regard for its land and its history, one of the wellsprings for a new land ethic supported by a renewed sense of our national identity. NATURAL AREAS, 1964-1972 Ten new natural areas were authorized or established during this period, including five National Parks, four scientific National Monuments, and one National Scientific Reserve, an entirely new type of natural area. In addition two long-established scientific National Monuments were made National Parks and one reservation within National Capital Parks was accorded new status as a separate area. The list follows:

Five new National Parks and two more created out of existing National Monuments is a notable achievement in eight years. It would have been impossible without vigorous efforts by the National Park Service going back many years, aided by newly awakened public and Congressional interest, and the financial base provided when Congress authorized the Land and Water Conservation Fund in 1965. These seven National Parks brought the total number to 38 and added significantly to the geographical distribution and diversity of scenic and scientific values conserved in the System. Canyonlands National Park, Utah, was established in 1964 to protect a wild area of exceptional scenic, scientific, and archaeological interest at the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers in southeastern Utah. The park contains over 337,000 acres. Both rivers are entrenched in labyrinthine gorges, and above their confluence the landscape is dominated by a great plateau called the Island in the Sky. The park contains numerous petroglyphs made by Indians a thousand years ago. Congress authorized the Guadalupe Mountains National Park in 1966 "to preserve . . . an area in the State of Texas possessing outstanding geological values together with scenic and other natural values of great significance." The area had been proposed for inclusion in the System as early as 1933. The park's mountain mass and its adjoining lands contain 81,000 acres and protect portions of the world's most extensive and significant Permian limestone fossil reef. North Cascades National Park, Washington, embraces over half a million acres of wild alpine country containing jagged peaks, mountain lakes, glaciers, and wildlife. From the start this undertaking was surrounded by intense controversy involving clashes among timber and mining interests, conservationists, local governments, and several Federal agencies, including the Forest Service, the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, and the National Park Service. The park was finally authorized in 1968. Redwood National Park, California, was authorized the same year, also after long and bitter controversy, "to preserve significant examples of the primeval coastal redwood forests and the streams and seashores with which they are associated for purposes of public inspiration, enjoyment and scientific study." Redwood National Park is 46 miles long, north and south, and about 7 miles wide at its greatest width. It includes 30 continuous miles of Pacific Ocean shoreline which, with adjoining hills, ridges, valleys, and streams, protects 56,201 acres of redwood forest, bluffs, and beaches. The boundaries include three well-known California State Parks distinguished by their magnificent redwood groves — Prairie Creek, established in 1923; Del Norte in 1925; and Jedediah Smith in 1929. California has not yet chosen to transfer these lands to the United States, but they are conserved in co-operation with the Service, which administers adjoining Federal lands. Finally, Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota, was authorized in 1971 "to preserve, for the inspiration and enjoyment of present and future generations, the outstanding scenery, geological conditions, and waterway system which constituted a part of the historic route of the Voyageurs who contributed significantly to the opening of the Northwestern United States." The park is planned to contain some 220,000 acres of wild northern lake country. Arches National Monument, Utah, originally established in 1929 by Presidential proclamation under the provisions of the Antiquities Act, was made a National Park by Act of Congress approved November 12, 1971. The area protects giant arches, windows, pinnacles and pedestals, all the extraordinary products of erosion. On the same day, President Nixon approved legislation adding a substantial area of public lands to Canyonlands National Park, bringing its total to 337,258 acres. On December 18, 1971, Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah, originally proclaimed in 1937, was also made a National Park by Act of Congress. Three new scientific National Monuments were authorized by Acts of Congress during this period and one — Marble Canyon, Arizona — was proclaimed by President Johnson under provisions of the Antiquities Act of 1906. These actions increased the number of scientific National Monuments to 37 and widened somewhat the geographical distribution of natural areas preserved in the System. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska, protects world-renowned quarries containing outstanding deposits of well-preserved Miocene mammal fossils which throw light on an important chapter in evolution often called the Age of Mammals. Biscayne National Monument, Florida, preserves a significant example of a living coral reef in the Upper Florida Keys. Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado, protects a wealth of fossil insects, seeds and leaves of Oligocene period which survived in an ancient lake bed. The area includes a remarkable display of petrified Sequoia stumps. Marble Canyon National Monument, Arizona, protects a spectacular 50-mile canyon of the Colorado River between Glen Canyon and Grand Canyon . Ice Age National Scientific Reserve was authorized by Congress in 1964— a new type of natural area in the National Park System. It is a cooperative undertaking between the Federal Government and the State of Wisconsin, "to assure protection, preservation, and interpretation of the nationally significant values of Wisconsin continental glaciation, including moraines, eskers, kames, kettleholes, drumlins, swamps, lakes, and other reminders of the ice age." The act authorized the Secretary of the Interior to formulate a comprehensive plan for the area in cooperation with State and local governmental authorities who will continue to own the lands with the Federal Government providing assistance in the form of grants. As amended in 1970 the law provides that in addition to grants made pursuant to the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965, the Secretary of the Interior is authorized to make grants not to exceed twenty-five percent of the actual cost of each development project within the reserve to a total not exceeding $425,000. In addition the Secretary is authorized to pay up to fifty percent of the annual costs of management, protection, maintenance, and rehabilitation. These are unusual provisions and their implementation by the Service and the State will be followed with close attention by park conservationists. Ice Age National Scientific Reserve may become the prototype for a new kind of natural area in the System. Although ten significant new natural areas were added between 1964 and 1972, their importance was overshadowed by enactment of the Wilderness Act. That act was a response to deepening national concern for the preservation of America's remaining wilderness in the face of mounting pressures from burgeoning technology, growing population, rising incomes, and increasing leisure time and mobility (78,000,000 automobiles in 1967). After years of passionate effort by devoted conservationists, Congress passed the Wilderness Act in 1964, a milestone in conservation history. The act read in part:

The act defined wilderness as "an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." For purposes of the act, wilderness was also defined as an area of undeveloped Federal land, primeval in character, without permanent improvements or human habitation, protected and managed to preserve its natural conditions. Wilderness areas should contain at least 5,000 acres of land. The act required the Secretary of the Interior to review, within ten years, every roadless area of 5,000 contiguous acres or more in the National Parks, National Monuments, and other units of the National Park System and report to the President on the suitability or unsuitability of each such area for preservation as wilderness. A recommendation from the President to Congress to designate a particular wilderness area would become effective only if approved by Act of Congress. The National Park Service has recently been engaged in a massive effort to complete a review of all roadless areas within the National Park System by 1974. By January 1, 1972, many potential wilderness areas had been studied and two — Petrified Forest and Craters of the Moon — had been designated by Acts of Congress. As the first century of the history of the National Park System drew toward a close, much remained to be done fully to carry out the provisions of the Wilderness Act, but more than a score of wilderness areas appeared to be nearing designation within the System. Director Hartzog substantially broadened and strengthened the Natural Landmarks Program in 1970. On August 18 the Federal Register published an official list of 150 Natural Landmarks, located in 41 States then eligible for entry on the National Registry. The list was accompanied by a statement from the Director which officially set forth for the first time the principal natural history themes according to which natural lands would henceforth be inventoried and classified by the National Park Service, as follows:

Criteria for Natural Landmarks to be designated within these themes were also set forth and examples given of the kinds of areas which could qualify. They included outstanding geological formations; significant fossil evidence; an ecological community illustrating a physiographic province; a habitat supporting a vanishing, rare, or restricted species; a relict fauna or flora; examples of scenic grandeur; and others. For our purposes the establishment of natural history themes and criteria is full of significance for the possible direction of future growth of the Family Tree. Just as historical themes undergird the Historical Area segment of the National Park System so too natural history themes will undergird the future growth — not only of the National Registry of Natural Areas — but also of the entire Natural Areas segment of the System. HISTORICAL AREAS, 1964-1972 Twenty-nine historical areas were added to the System between 1964 and 1972 and two were consolidated bringing the total number to 172. These new historical areas were located in 21 States and the District of Columbia, further extending the System's geographical representation. They were distributed among eight of nine major themes in American history as follows:

Limits of space preclude detailed comments on these many individual areas, though each is unique. A few highlights, suggestive of general trends, deserve special attention. There was a notable continuation of the previous tendency to preserve places associated with the lives of American Presidents in the National Park System. Seven former Presidents were honored in this manner between 1964 and 1972. In the order of their presidencies, they were Abraham Lincoln at his home in Springfield, Illinois; Theodore Roosevelt at the Ansley Wilcox House, Buffalo, New York, where he took the oath of office following the assassination of William McKinley; William Howard Taft at his birthplace and early home in Ohio; Herbert Hoover at his birthplace, boyhood home, and burial place, West Branch, Iowa; Dwight David Eisenhower at his home and farm, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; John Fitzgerald Kennedy at his birth place and boyhood home, Brookline, Massachusetts; and Lyndon B. Johnson at his birthplace and boyhood home in Texas. In addition, the handsome Theodore Roosevelt Memorial situated in natural surroundings on Theodore Roosevelt Island, Washington, D. C., was dedicated by President Johnson on October 27, 1967. Designed by Eric Gugler, the memorial incorporates a seventeen-foot bronze statue of Roosevelt by Paul Manship in an oval terrace ornamented by two fountains and tour granite slabs inscribed with tenets of Roosevelt's philosophy of citizenship. Seven other Presidents are also represented in the National Park System by historic sites or memorials. Other additions to historical areas during this period are fairly evenly distributed among seven themes, two or three sites for each. It may be noted that two sites were added under Theme VIII, The Contemplative Society — homes of the American sculptor, Saint-Gaudens, and the poet and writer, Carl Sandburg. With these additions the System now contains three sites representing the Contemplative Society. Three sites were added under Theme IV, Major American Wars — George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, Indiana, the Andersonville Prison site in Georgia, and Fort Point. California. With these additions the System now contains 36 sites commemorating Major American Wars. The contrast in representation between Theme VIII, The Contemplative Society, with a total of three sites and Theme IV, Major American Wars, with 36 is striking and deserves reflection. New directions for historic preservation within the National Park System were developed further during this period in two unusual undertakings — the Nez Perce National Historical Park, Idaho, and the Fort Scott Historic Area, Kansas, both authorized in 1965. Though quite different, both projects involve continuing cooperative arrangements between the National Park Service, the States, other political subdivisions, and quasi-public and private organizations and individuals. The Nez Perce National Historical Park provides an instrument for coordinating the preservation and interpretation of 23 related historic sites geographically distributed over 12,000 square miles in northern Idaho. These sites represent the history and culture of the Nez Perce Indians and of the whites who eventually engulfed them — explorers, fur traders, missionaries, soldiers, settlers, gold miners, loggers, and farmers. The sites in this park include historic Nez Perce gathering places, explorers' campsites, historic missions, battlefields, natural formations, and historic Lolo Trail and Pass under a variety of ownerships and will so continue. The park is a joint venture between the National Park Service, other Federal agencies, the State of Idaho, several local governments, the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee, private organizations and generous individuals. The Secretary of the Interior has an important coordinating role. Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, authorized in 1948, involves similar cooperative relationships and served as a partial precedent for Nez Perce. Ice Age National Scientific Reserve is a somewhat parallel example of cooperative relationships in the field of natural areas but under state management. Fort Scott Historic Area, Kansas, authorized by Congress in 1965 also illustrates a new type of cooperative historic preservation project. The act authorized the Secretary of the Interior to commemorate and mark — but not acquire as Federal property — the sites of certain historical events in Kansas that occurred between 1854 and the outbreak of the Civil War. These include Fort Scott; sites associated with John Brown in Osawatomie; Mine Creek Battlefield; and the sites of the Marais des Cynges massacre and Quantrell's raid. The Secretary was also authorized, under certain conditions, to make grants to the city of Fort Scott for land acquisition and development necessary to display the fort to the public and to provide historical information to enhance public understanding. All these authorizations were contingent upon the execution of satisfactory cooperative agreements with the city or other property owners. The importance of the addition of 29 historical areas to the System between 1964 and 1972, notable as it is, was over-shadowed by the deeper significance of passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. This landmark legislation grew out of recommendations made by a Special Committee on Historic Preservation established in 1965 under the auspices of the United States Conference of Mayors with a grant from the Ford Foundation. The eleven-member committee was headed by Hon. Albert Rains, for many years a distinguished Representative in Congress from Alabama and former Chairman, Housing Subcommittee of the House, and included high ranking officials of Federal, State, and local governments and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Its report With Heritage So Rich, published early in 1966, spoke eloquently of the depth and diversity of our historical heritage, the mounting dangers to its preservation, and the need for a new and broadened national preservation policy and program. Congress responded to the Rains Committee report, and to strong recommendations from the Secretary of the Interior and other Federal officials, notably Director Hartzog, by enacting the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, signed by President Johnson on October 15. The new law greatly enlarged the scope and character of National Park Service participation in the historic preservation movement in the United States. (1) It authorized the Secretary of the Interior to expand and maintain a National Register of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects significant in American history, architecture, archaeology, and culture. By March 1, 1972, the National Register of Historic Places contained some 3,614 entries, with many additions being made each year. (2) It authorized a program of matching grants-in-aid to the States to help them prepare comprehensive statewide historic preservation surveys and plans. By 1972 survey and planning grants had been made to most of the States totaling over $2.25 million dollars annually. (3) It authorized matching grants to the States for "brick and mortar" acquisition and preservation projects. By 1972 grants had been made under this authority for some 175 projects widely distributed through most of the States, and additional grants were being authorized annually. (4) It authorized matching grants to assist the National Trust for Historic Preservation to meet its responsibilities under its Congressional charter. By 1972 the National Trust was receiving over $1 million dollars in grants annually. (5) It established a high-level Advisory Council on Historic Preservation whose members include the Secretaries of Interior, Commerce, Treasury, Housing and Urban Development, the Attorney General, the Administrator of the General Services Administration, the Chairman of the National Trust, and ten interested and experienced citizens. The Council's duties include advising the President and Congress on matters relating to historic preservation. The Director of the National Park Service or his designee is Executive Director of the Council. (6) It established procedures to insure that no registered site or building would be adversely affected by a Federal or Federally assisted undertaking or licensing action without first giving the Advisory Council formal opportunity to comment. Congressional and Presidential interest in this program continues to be strong. In 1970 Congress amended the National Historic Preservation Act to add the Secretaries of Agriculture, Transportation, and the Smithsonian Institution to the Advisory Council; provide for United States' participation in the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (Rome Centre); and extend the appropriation authority for grants three additional years at an additional total authorization of 32 million dollars. In 1971, President Nixon took another major step to strengthen Federal participation in historic preservation. On May 13 he signed Executive Order 11593 calling for "Protection and Enhancement of the Cultural Environment." In an accompanying statement he said:

The order is now being implemented. Some fifty Federal agencies have designated representatives to work with the National Park Service on historic preservation matters. Each agency is required to locate, inventory, and nominate to the Secretary of the Interior by July 1, 1973, all sites, buildings, districts and objects under its jurisdiction or control that appear to qualify for listing on the National Register. Thereafter, among other responsibilities, each agency is required to initiate measures to provide for the maintenance of such registered sites, through preservation, rehabilitation, or restoration at professional standards prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior. There are estimated to be thousands of significant historic sites and structures on military reservations, public lands, national forests, and other Federal holdings to which new protection will now be extended in cooperation with the National Park Service. Through these various means, the National Park Service is now stimulating new historic preservation efforts at the grass roots level throughout the United States. This was one of the principal purposes of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 — to see to it that the historical and cultural foundations of the Nation are "preserved as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people." RECREATION AREAS, 1964-1972 Between 1964 and 1972, 20 new recreation areas, situated in 35 of the 50 States, were added to the National Park System. Eight were National Seashores or Lakeshores, eight reservoir-related Recreation Areas, three National Scenic Riverways, and one a National Scenic Trail. The last two categories were entirely new to the System. These additions more than doubled the number of recreation areas, increasing it from 17 to 36. The list of additions follows:

The rapid growth in the number of recreation areas in the System during the period was a consequence of several factors including groundwork laid by the Service in earlier surveys and creation of the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Concurrently with those developments, President John F. Kennedy formed a Recreation Advisory Council composed of the Secretaries of the Interior, Agriculture, Defense, Commerce, and Health, Education and Welfare, plus the Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, to coordinate Federal programs for outdoor recreation. In 1963, the Council's Policy Circular No. 1 established criteria for new National Recreation Areas. The Council expected new National Recreation Areas to be established by act of Congress and to be limited in number since most of the outdoor recreation needs of the American people should be met locally. Whatever their type — Seashore, Lakeshore, Riverway, or Reservoir — National Recreation Areas were expected to be spacious, including as a rule not less than 20,000 acres of land and water, with high recreation carrying capacity based on interstate patronage. They were also to have natural endowments well above the ordinary in quality and recreation appeal, transcending that normally associated with State and local recreation areas but less significant than the unique scenic and historic elements of the National Park System. They were to be situated where crowded urban populations could easily reach them and to be of a nature justifying Federal investment. While some National Recreation Areas would be incorporated into the National Park System others would be managed by the Forest Service, the Corps of Engineers, and possibly other Federal agencies. Within this general framework, 20 Recreation Areas were added to the System between 1964 and 1972, classified into four types as follows: National Seashores and Lakeshores Eight new National Seashores and Lakeshores were authorized in seven years, tripling their number — a sparkling accomplishment. Preservation of most of these areas had been actively sought by the Service since the 1950's when seashore surveys were largely completed. There are now 12 such areas in the System, including five along the Atlantic shoreline, two along the Gulf coast, one on the Pacific coast, and four around the Great Lakes. These areas reflect the national determination to save significant and unspoiled examples of all our vanishing shorelines while it is still possible. In most cases creation of these reservations stabilized a rapidly deteriorating shoreline landscape threatened by real estate subdivisions highway construction, and commercial development and preserved natural and historical values in imminent danger of loss. At the same time they provided important outdoor recreational opportunities in a natural environment while holding back from offering facilities for mass recreation in the Jones Beach style of highly intensive use. The balance between preservation and use contemplated by Congress varies from area to area. Fire Island National Seashore protects some 25 miles of the largest remaining barrier beach off the south shore of Long Island, 50 miles from downtown Manhattan. It contains relatively unspoiled and undeveloped beaches, dunes, and other natural features. The Secretary is to administer Fire Island "with the primary aim of conserving the natural resources located there." Assateague Island preserves a 35-mile barrier island of beach, marsh, ground cover, and marine and wildlife along the Maryland-Virginia portion of the Atlantic Ocean shoreline. The boundary embraces the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge and Assateague State Park, which continue as separate reservations although management plans are coordinated. The Secretary is directed by law to administer the area "for general purposes of public outdoor recreation, including conservation of natural features contributing to public enjoyment." Cape Lookout, North Carolina, authorized in 1966, protects three barrier islands of the Outer Banks below Cape Hatteras, embracing beaches, dunes, salt marshes, and Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi, was authorized on January 8, 1971, to protect four Gulf Coast islands, a portion of Perdido Key, the ancient Naval Live Oaks Reservation, and several historic Spanish and American forts "for public use and enjoyment." Pictured Rocks, Michigan, was the first of four successive National Lakeshores authorized by Congress. When completed it will embrace a unique scenic area on the south shore of Lake Superior some 32 miles long containing multi-colored sandstone cliffs, broad beaches, bars, dunes, waterfalls, inland lakes, ponds, marshes, hardwood and coniferous forests, and abundant wildlife. These resources are to be preserved "for the benefit, inspiration, education, recreational use, and enjoyment of the public." Indiana Dunes, Indiana, protects a section of the southern shore of Lake Michigan between Gary and Michigan City containing beaches, 200-foot high sand dunes, and hinterlands. This area was proposed as a National Park as long ago as 1917 but failed because of World War I. A State Park was established there in 1923. The preservation and public use clauses of the law are patterned after those for Cape Cod. Apostle Islands, Wisconsin, was authorized to protect 20 of the 22 Apostle Islands and an 11-mile strip of adjacent Bayfield Peninsula along the south shore of Lake Superior. These clustered islands are heavily forested, with shores marked by steep slopes, picturesque arches and pillars of stone, and protected bays and inlets with white sand beaches. Sleeping Bear Dunes, Michigan, the fourth National Lakeshore, preserves outstanding natural features, including forests, beaches, dune formations, and ancient glacial phenomena along a 34-mile stretch of the eastern mainland shore of Lake Michigan together with similar resources on nearby North and South Manitou Islands. Reservoir-related Recreation Areas. Eight new public reservations were added to the National Park System during this period to conserve and use recreational resources surrounding major Federal reservoirs. These additions brought the total number to thirteen. Four of these new areas — Bighorn Canyon, Delaware Water Gap, Lake Chelan and Ross Lake — were authorized by special Acts of Congress and are named National Recreation Areas Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area, Montana-Wyoming embraces a 71-mile-long reservoir called Bighorn Lake, impounded behind Yellowtail Dam, constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation across the Bighorn River in the heart of the Crow Indian Reservation The lower 47 miles of the reservoir lie within the rugged, steep-walled Bighorn Canyon. Ross Lake and Lake Chelan National Recreation Areas, Washington, were authorized in 1968 as reservations contiguous with and complementary to North Cascades National Park. They were planned as areas in which to concentrate the locations of physical developments especially accommodations for visitors next to but outside the National Park — the first time a provision of this particular type has been made at the very outset in conjunction with the establishment of a National Park. The Ross Lake area lies between the North and South Units of the National Park, bisecting it. It includes most of 24-mile Lake Ross, the lands on either side, and Diablo Lake and portions of the Skagit River valley. The Lake Chelan area adjoins the National Park on the southeast but embraces only a small part of the artificial lake, The North and South Units of the National Park and these two National Recreation Areas collectively embrace 1,053 square miles of magnificent mountain country in the Cascade Range near the Canadian border. Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, Pennsylvania-New Jersey, was authorized by Congress in 1965 to encompass the Corps of Engineers' 37-mile-long Tocks Island Reservoir, and 70,000 acres of outstanding scenic lands in the adjoining Delaware Valley, including the famous Delaware Water Gap. This National Recreation Area is the only one in the System east of the Mississippi River. It is located within approximately 50 miles of New York City and 90 miles of Philadelphia, and has been planned to serve ten million visitors annually. Within the last two years, however, the concept underlying the Tocks Island Dam, a unit in the comprehensive plan for the Delaware River Basin, has been vigorously attacked by many conservationists on the grounds that it will seriously damage the natural Delaware Valley environment, and contradict policies adopted by Congress in the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. The protests against Echo Park Dam in Dinosaur National Monument during the 1950's, and later over Lake Powell and Glen Canyon, reflected a similar viewpoint. Now, however, the National Environmental Policy Act has made it obligatory for Federal agencies to evaluate and report on environmental effects previously ignored or at best treated lightly. The current struggle over plans for Tocks Island Dam and the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area may well foreshadow vigorous environmental protests against new reservoirs in relatively unspoiled country and against their accompanying recreation areas. If this proves to be the case, this sub-category in the System may be slow to grow in the future. Four other reservoir-related recreation areas — Amistad, Arbuckle, Curecanti and Sanford — were established during this period by cooperative agreements between the National Park Service and other agencies pursuant to legislation enacted in 1946. That legislation authorized the use of Service appropriations for the "administration, protection, improvement and maintenance of areas, under the jurisdiction of other agencies of the Government, devoted to recreational use pursuant to cooperative agreements." These four are simply called Recreation Areas. Amistad Recreation Area, Texas, has unique features because it is on the international boundary between the United States and Mexico. Amistad Dam, constructed across the Rio Grande by the International Boundary and Water Commission, was dedicated by Presidents Nixon and Diaz Ordaz on September 8, 1969. The dam impounds Amistad Lake, which will extend 74 miles up the Rio Grande and have an 850-mile shoreline of which 540 miles will be in Texas. By cooperative agreement with the International Boundary and Water Commission, the National Park Service is responsible for planning, constructing, and managing recreational facilities and programs for the public on the United States side of the international reservoir. It is an unusual responsibility, even for the National Park Service. Arbuckle Recreation Area, Oklahoma, is situated within a few miles of Platt National Park, with which it is jointly administered. It embraces the eight-mile-long Lake of the Arbuckles impounded by the Bureau of Reclamation's Arbuckle Dam and adjoining recreational lands. Curecanti Recreation Area, Colorado, comprises three reservoirs and adjacent lands located in the deep canyons of Gunnison River in western Colorado. These reservoirs are or will be impounded behind three dams constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation — the Blue Mesa, Morrow Point and Crystal Dams — all elements in the Curecanti Unit of the Colorado River Storage Project. Sanford Recreation Area, Texas, embraces 20-mile-long Lake Meredith and adjoining lands. The reservoir is impounded behind the Bureau of Reclamation's Sanford Dam on the Canadian River. The Recreation Area adjoins the Alibates Flint Quarries and Texas Panhandle Pueblo Culture National Monument near the south side of Lake Meredith. The obverse of a recreation area established around a reservoir behind a dam is one created to preserve a free-flowing river for its own value. This new and alternative concept for river-related recreation brings us to the next category. National Scenic Riverways. A new kind of Recreation Area was introduced into the National Park System in 1964. On August 27 of that year Congress authorized establishment of the Ozark National Scenic Riverways in Missouri, the first National Riverway. This new area is in effect an elongated park, embracing all or stretches of two wild, free-flowing rivers, the Current and Jacks Fork, which flow unimpeded for 140 miles. The park is planned to protect 113 square miles of land and water managed to provide many recreational benefits while preserving scenic, scientific, and natural qualities. Land acquisition arrangements are marked by sensitive regard for the respective interests of Federal, State, and local governments and private owners of improved property. Three Missouri State Parks — Big Springs, Alley Springs, and Round Spring — which protect significant caves and springs have been added to Federal holdings with the consent of the State. The National Park Service is undertaking a comprehensive recreational program on the riverways, with emphasis on preserving and interpreting their natural wonders and interesting early-American folk culture. Ozark National Scenic Riverways reflected a determination in Congress to take new steps to protect America's natural environment, so widely threat ened by such forces as the population explosion and the juggernaut of modern technology. On October 2, 1968, President Johnson signed a comprehensive new law to provide for a National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. It contains a statement of national policy highly important to the National Park System:

The act established three kinds of riverways: (1) wild river areas, (2) scenic river areas, and (3) recreational river areas. It identified eight rivers and adjacent lands in nine States as the initial components of the national wild and scenic rivers system — St. Croix, Minnesota and Wisconsin; Wolf, Wisconsin; Eleven Point, Missouri; Middle Fork of the Clearwater, Idaho; Feather, California; Rio Grande, New Mexico; Rogue, Oregon; Middle Fork of the Salmon, Idaho. The first three were to be administered by the Secretary of the Interior, the next four by the Secretary of Agriculture, and the last by either as might be subsequently determined. Twenty-seven other riverways were identified as potential additions to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System and their study authorized. It was anticipated that of these some would be designated and managed by States and their political subdivisions provided they met national criteria. St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, placed under Service jurisdiction in 1969, protects lands and waters along some 200 miles of the lovely St. Croix River and its Namekagon tributary. It is canoe country marked by wildness, solitude, clear flowing water, and abundant wildlife. Under the comprehensive plan for this riverway, the Northern States Power Company early announced its intention to donate 25,000 acres of its property along the St. Croix River to public agencies, about 7,000 acres going to the National Park Service, 13,000 to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and 5,000 to its Wisconsin counterpart. These transfers with some subsequent adjustments are taking place over a period of years. The Wolf National Scenic Riverway was scheduled to be placed under Service jurisdiction in 1969, to protect 24 miles of fast, wild water ideal for canoeing, fishing, and scenic enjoyment. The land involved must be acquired from the Menominee Indians who have so far been unwilling to part with it. Establishment of the area awaits resolution of this problem. National Scenic Trails. The year 1968 was remarkable for conservation legislation. On the same day he approved the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, President Johnson also signed the National Trails System Act. It established another highly significant national policy:

The act provided for recreational trails, scenic trails, and connecting or side trails. National Scenic Trails may be designed only by Act of Congress. National Recreation Trails may be designated, under certain circumstances by the Secretary of the Interior or the Secretary of Agriculture. The act established two National Scenic Trails as initial components of the National Trails System: (1) the Appalachian Trail in the eastern United States, extending approximately 2,000 miles along the crest of the Appalachian Mountains from Mount Katahdin, Maine, to Springer Mountain, Georgia, to be administered by the Secretary of the Interior, in consultation with the Secretary of Agriculture; and (2) the Pacific Crest Trail, extending 2,350 miles northward from the Mexican-California boundary along the mountain ranges of the West Coast States to the Canadian-Washington border near Lake Ross, to be administered by the Secretary of Agriculture in consultation with the Secretary of the Interior. The act requested the two Secretaries to study the routes of 14 other trails as potential additions to the National Trails System. The Appalachian National Scenic Trail was established in 1968 and immediately added to the National Park System. The Trail has a long history. It was conceived in 1921 by Benton Mackaye, forester, philosopher, and dreamer, who thought the trail should be the backbone of a primeval environment, a refuge from a mechanized civilization. Initially four older New England trail systems, including the Long Trail in Vermont, begun in 1910, were linked to begin the Appalachian Trail. Additions were made farther south, including long sections through National Forests in Virginia and North Carolina. The initial Trail was completed from Georgia to Maine in 1937 when the last two miles were opened on Mount Sugarloaf in Maine. The Secretary of the Interior has appointed an Advisory Council for the Appalachian National Scenic Trail including members to represent each of 14 States, the Appalachian Trail Conference and other private organizations, and involved Federal agencies. The official trail route was designated by the National Park Service by notice in the Federal Register on October 9, 1971. The Secretary of the Interior is responsible for development and maintenance of the Trail within federally administered areas, but encourages the States to operate, develop, and maintain portions of the trail Outside federal boundaries. During 1972, studies of four other potential National Scenic Trails were being conducted by the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in cooperation with the National Park Service, the Forest Service, the States, and other agencies. Special attention was being given to (1) Continental Divide Trail from the Mexican to the Canadian border; (2) Potomac Heritage Trail, from the mouth of the Potomac River to its source including the 170-mile Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath; (3) North Country Trail, linking the Appalachian Trail in the Vermont-New York vicinity to the Lewis and Clark Trail in North Dakota; and (4) the Oregon Trail from Independence, Missouri, to Fort Vancouver, Washington. These studies will include recommendations on the proposed Federal administering agency, which in some cases, perhaps in several, is likely to be the National Park Service. Under the new law components of the National Trails System will include not only National Scenic Trails but also National Recreation Trails. On June 2, 1971, Secretary of the Interior Rogers C. B. Morton designated 27 new National Recreation Trails in 19 States and the District of Columbia. Of these, 20 will be administered by state or local authorities and the remainder by Federal agencies. One of these National Recreation Trails is situated within the National Park System—the Fort Circle National Recreation Trail, 7.9 miles long, within National Capital Parks. NATIONAL CAPITAL PARKS AND URBAN PARKS, 1964-1972 We have not traced the important history of National Capital Parks after becoming a part of the System in 1933. Suffice it to say here that a great deal was accomplished during those decades to focus national attention on National Capital Parks as an outstanding example of urban park lands and programs. The Natural Beauty program of the 1960's as developed in Washington, D. C., under the leadership of Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson made a particularly conspicuous impression on the nation. Between 1964 and 1972, National Capital Parks continued its significant role as a demonstration area for urban park programs for the nation. A Summer-in-the-Parks program was initiated in National Capital Parks in 1967 to provide supervised recreation for deprived city children and others. It has been expanded to a program called Parks for All Seasons, and the ideas and techniques are now being exported by the Service to other interested major American cities. Other innovative programs include development of an integrated bicycle and walking trail system for Washington, D. C., and the surrounding counties, and leadership in environmental education. As the first century of National Parks drew to a close, proposals were being developed for National Urban Recreation Areas in several major American cities in addition to Washington, D. C. Best known and farthest advanced in Congress was a proposal for Gateway National Recreation Area in the New York City metropolitan area to include lands at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and Breezy Point Beach, Jamaica Bay, Floyd Bennett Field, and possibly other areas. On February 7, 1972, President Nixon proposed legislation to establish a Golden Gate National Recreation Area in and around San Francisco Bay. Altogether the area would encompass some 24,000 acres of fine beaches, rugged coasts and readily accessible urban parklands, extending approximately 30 miles along some of America's most beautiful coastline, north and south of Golden Gate Bridge. There is mounting national emphasis on the importance of meeting and solving longstanding problems of deteriorating urban centers in America including their park and recreation problems. The Bureau of Outdoor Recreation has helped focus public attention on needs and opportunities in this field. By considering establishing National Urban Recreation Areas, the National Park Service is endeavoring to make a constructive response to this emerging and urgent national need. In order to develop appropriate responses to this public desire and need, the Service, with approval of the Secretary of the Interior's Advisory Board, has established a new category of parks, Cultural Areas. This category is another expression of the trend represented in other phases of Service work by the Living History programs, and certain aspects of environmental education. As the first century of National Parks drew toward its close, the System included its first Cultural Park, Wolf Trap Farm Park for the Performing Arts, officially opened to the public on July 1, 1971. Others are actively proposed, suggesting that the concept may receive major implementation. CULTURAL AREAS, 1966-1972 Through the generosity of an imaginative benefactress, a new type of area was added to the National Park System in 1966. The benefactress was Mrs. Catherine Filene Shouse and the area was her estate, Wolf Trap Farm, in the Virginia hills of Fairfax County, half an hour from Washington, D. C. Mrs. Shouse donated Wolf Trap Farm, containing 117 acres, to the United States in order that it might be preserved as a center for the performing arts in the National Capital area. Congress authorized establishment of the area on October 15, 1966. A handsome auditorium named Filene Center has been built in a ten-acre clearing. It seats some 3,500 spectators and there is room for 3,000 more on adjoining lawns. During the summer of 1971 a 10-week inaugural season of concerts, opera, and ballet was launched at Wolf Trap Farm, with the aid of a private foundation. The summer's performances were widely applauded. Perhaps more importantly, initial steps were taken to form the Wolf Trap Company from some 60 young people selected in nationwide auditions. In cooperation with American University, Wolf Trap also gave credit courses in the performing arts to some 800 high school and college students during the summer of 1971. Because it has been an exceptional success, Wolf Trap Farm is looked upon by the National Park Service as a possible prototype for a new type of unit in the System — a cultural park. Of course every unit in the System — natural, historical, or recreational — is also cultural. Nevertheless, the Service has become keenly aware of certain currents in contemporary American life that suggest a strong desire among the American people to observe and participate in a wide range of cultural activities, from the revival of folk arts to the enjoyment of the performing arts. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||