CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site

|

NPS Centennial Monthly Feature

As we explore the history of the National Park Service, this month we explore the evolution of the National Park System. The first edition of The National Parks: Shaping the System was written by Barry Mackintosh in 1985. This final edition was released in 2005. Whereas the System was comprised of 388 units in 2005, at last count the System now totals 412 units (and counting), so the System continues to be shaped.

Produced by U.S. Department of the Interior

From the Director The Statue of Liberty, Yellowstone, Everglades, Grand Canyon, Independence Hall, Carlsbad Caverns — these names are known to school children and adults throughout the United States and around the world. The places these names represent are only a few of the 388 natural, cultural, and recreational areas that make up the National Park System. This collection of special places welcomes upwards of 280 million visitors every year who come to learn, enjoy, and be awed and inspired. Congress has described the System, which includes some of the most significant historic and natural places in the nation, as "cumulative expressions of a single national heritage." These national parks form the backbone of a nationwide system of local, county, state, and regional parks that provides recreational and educational opportunities for everyone. The story of the creation of this amazing system of parks is the subject of this book. It begins in 1832 in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and threads its way through the Yosemite Valley, across the bloodied fields at Gettysburg and Shiloh, along the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, and down to seashores along the Pacific and Atlantic coasts and the Gulf of Mexico. It speaks to a determined and prolonged effort to set aside and preserve some of the best places this country possesses. It is my honor to serve as the 16th Director of the National Park Service as we protect and preserve this national legacy. It is also my great pleasure to present this story to you. I hope it will inspire and inform and spark your interest in participating in the richness of the National Park System. As always, I'll see you in the parks! Fran P. Mainella, Director

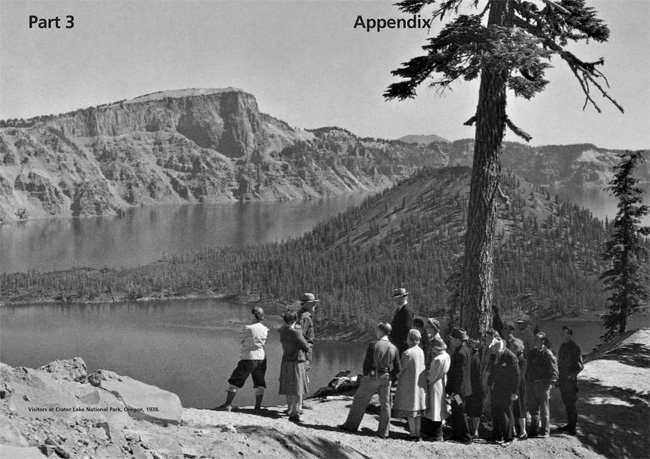

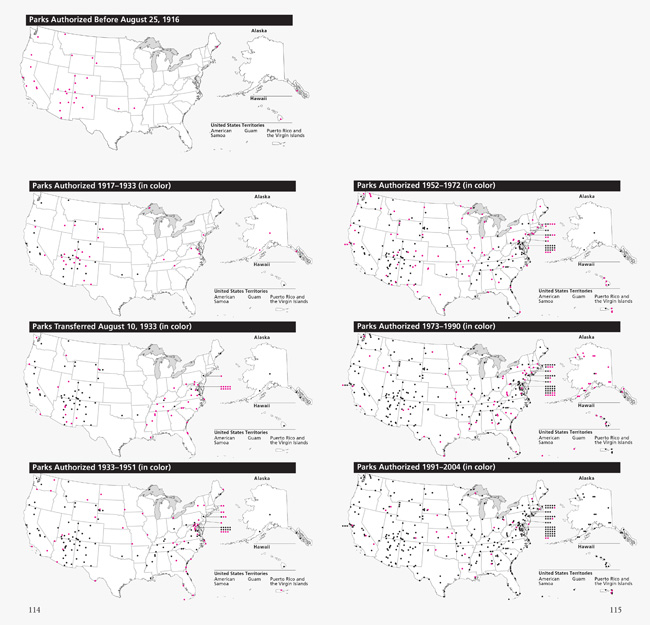

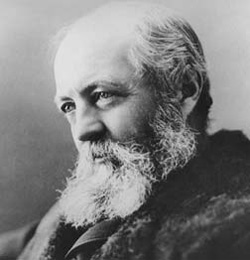

Using this Book This book tells the story of the evolution of the U.S. National Park System, the first of its kind in the world. In Part 1 former Bureau Historian Barry Mackintosh discusses the origins of the System and describes the complexity of its designations. In Part 2 Mackintosh chronicles the step-by-step growth of the System from its beginnings to its 388 areas at the beginning of 2005. Part 3 contains maps showing the extent of the System and its growth over time, a list of all National Park Service directors with their tenures, a feature on individuals who helped make the System what it is today, and suggested readings. This is the third print edition of The National Parks: Shaping the System, which was first published in 1985. The text has been updated by Bureau Historian Janet McDonnell.

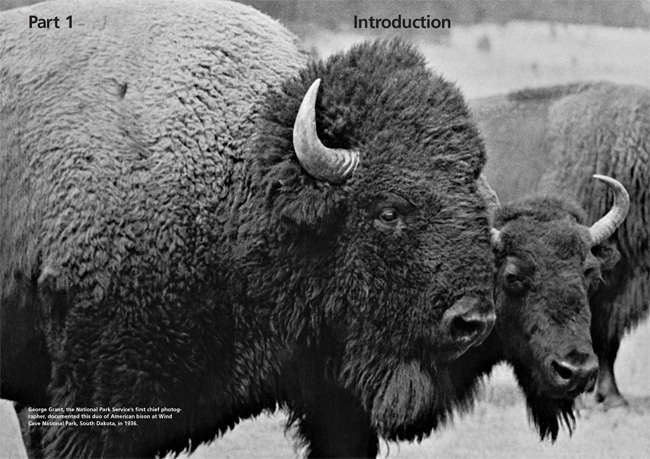

Part 1 A Few Words About This Book When did the National Park System begin? The usual response is 1872, when an act of Congress created Yellowstone National Park, the first place so titled. Like a river formed from several branches, however, the System cannot be traced to a single source. Other components—the parks of the Nation's Capital, Hot Springs, parts of Yosemite — preceded Yellowstone as parklands reserved or established by the Federal Government. And there was no real "system" of national parks until Congress created a federal bureau, the National Park Service (NPS), in 1916 to manage those areas assigned to the U.S. Department of the Interior. The systematic park administration within Interior paved the way for annexation of comparable areas from other federal agencies. In a 1933 government reorganization, the National Park Service acquired the War Department's national military parks and monuments, the Agriculture Department's national monuments, and the national capital parks. Thereafter the NPS would be the primary federal agency preserving and providing for public enjoyment of America's most significant natural and cultural properties in a fully comprehensive National Park System. Ronald F. Lee's Family Tree of the National Park System, published by the Eastern National Park and Monument Association in 1972, chronicled the System's evolution to that date. Its usefulness led the NPS to issue a revised and expanded account titled The National Parks: Shaping the System in 1985. This is the third print edition of that publication, reflecting the System's continued growth and diversity. The nomenclature of National Park System areas is often confusing. System units now bear some 30 titles besides "national park," which commonly identifies the largest, most spectacular natural areas. Other designations such as national seashore, national lakeshore, national river, and national scenic trail are usefully descriptive. In contrast, the national monument title — applied impartially to large natural areas like Dinosaur and small cultural sites like the Statue of Liberty — says little about a place. For no obvious reason, some historic forts are national monuments and others are national historic sites, while battlefields are variously titled national military parks, national battlefields, and national battlefield parks, among other things. All these designations are rooted in the System's legislative and administrative history. Where distinctions in title denote no real differences in character or management policy, the differing designations usually reflect changes in fashion over time. Historical areas that once would have been named national monuments, for example, more recently have been titled national historic sites, if small, or national historical parks, if larger. Regardless of their titles, all System units are referred to generically as "parks," a practice followed in this book. The dates used here for parks are usually those of the earliest laws, Presidential proclamations, or departmental orders authorizing or establishing them. In some cases these actions occurred before the areas were placed under NPS administration and thus in the National Park System. In 1970 Congress defined the System as including "any area of land and water now or hereafter administered by the Secretary of the Interior, through the National Park Service, for park, monument, historic, parkway, recreational, or other purposes." This legal definition excludes a number of national historic sites, memorials, trails, and other areas assisted or coordinated, but not administered, by the NPS. Lee's Family Tree, with its chronological listing of park additions and concise discussion of significant examples, developments, and trends, was a valuable orientation and reference tool for NPS personnel and others tracking the System's growth to Yellowstone's centennial year. It is hoped that this revised edition of Shaping the System, still owing much to Lee's work, will serve the same purposes for the present generation of park employees and friends.

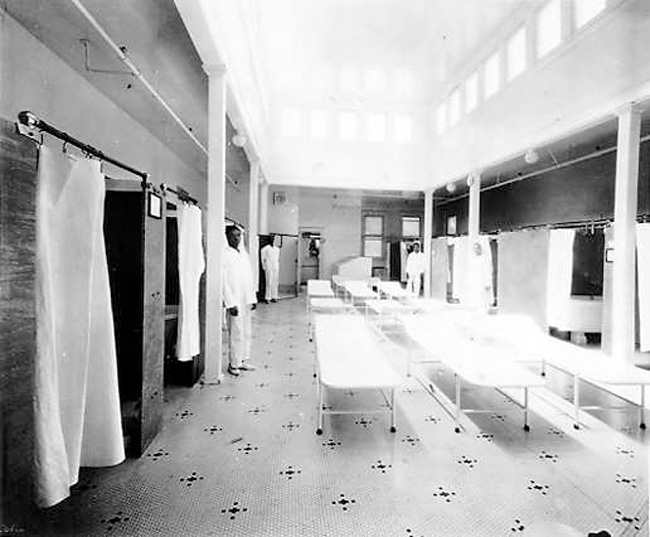

Part 2 Before the National Park Service National Parks The national park idea — the concept of large-scale natural preserva tion for public enjoyment— has been credited to the artist George Catlin, best known for his paintings of American Indians. On a trip to the Dakota region in 1832, he worried about the destructive effects of America's westward expansion on Indian civilization, wildlife, and wilderness. They might be preserved, he wrote, "by some great protecting policy of government ... in a magnificent park a nation's park, containing man and beast, in all the wild[ness] and freshness of their nature's beauty!" Catlin's vision of perpetuating indigenous cultures in this fashion was surely impractical, and his proposal had no immediate effect. Increasingly, however, romantic portrayals of nature by writers like James Fenimore Cooper and Henry David Thoreau and painters like Thomas Cole and Frederick Edwin Church would compete with older views of wilderness as something to be overcome. As appreciation for unspoiled nature grew and as spectacular natural areas in the American West were publicized, notions of preserving such places began to be taken seriously. One such place was Yosemite Valley, where the national park idea came to partial fruition in 1864. In response to the desires of "various gentlemen of California, gentlemen of fortune, of taste, and of refinement," Sen. John Conness of California sponsored legislation to transfer the federally owned valley and nearby Mariposa Big Tree Grove to the state so they might "be used and preserved for the benefit of mankind." The act of Congress, signed by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, granted California the lands on condition that they would "be held for public use, resort, and recreation . . . inalienable for all time." The geological wonders of the Yellowstone region, in the Montana and Wyoming territories, remained little known until 1869-71, when successive expeditions led by David E. Folsom, Henry D. Washburn, and Ferdinand V. Hayden traversed the area and publicized their remarkable findings. Several members of these parties suggested reserving Yellowstone for public use rather than allowing it to fall under private control. The park idea received influential support from agents of the Northern Pacific Railroad Company, whose projected main line through Montana stood to benefit from a major tourist destination in the vicinity. Yosemite was cited as a precedent, but differences in the two situations required different solutions. The primary access to Yellowstone was through Montana, and Montanans were among the leading park advocates. Most of Yellowstone lay in Wyoming, however, and neither Montana nor Wyoming was yet a state. So the park legislation, introduced in December 1871 by Senate Public Lands Committee Chairman Samuel C. Pomeroy of Kansas, was written to leave Yellowstone in federal custody. The Yellowstone bill encountered some opposition from congressmen who questioned the propriety of such a large reservation. "The geysers will remain, no matter where the ownership of the land may be, and I do not know why settlers should be excluded from a tract of land forty miles square ... in the Rocky mountains or any other place," complained Sen. Cornelius Cole of California. But most were persuaded otherwise. The bill passed Congress, and on March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed it into law. The Yellowstone act withdrew more than two million acres of the public domain from settlement, occupancy, or sale to be "dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." It placed the park "under the exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior" who was charged to "provide for the preservation, from injury or spoliation, of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and their retention in their natural condition." The Secretary was also to prevent the "wanton destruction" and commercial taking of fish and game — problems addressed more firmly by the Lacey Act of 1894, which prohibited hunting outright and set penalties for offenders. With Yellowstone's establishment, the precedent was set for other natural reserves under federal jurisdiction. An 1875 act of Congress made most of Mackinac Island in Michigan a national park. Because of the Army's presence there at Fort Mackinac, the Secretary of War was given responsibility for it. Mackinac National Park would survive only 20 years as such: when the fort was decommissioned in 1895, Congress transferred the federal lands on the island to Michigan for a state park. The next great scenic national parks — Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite, all in California — did not come about until 1890, 18 years after Yellowstone. The initial Sequoia legislation, signed by President Benjamin Harrison on September 25, again followed that for Yellowstone in establishing "a public park, or pleasure ground, for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." Another act approved October 1 set aside General Grant, Yosemite, and a large addition to Sequoia as "reserved forest lands" but directed their management along park lines. Sequoia, General Grant (later incorporated in Kings Canyon National Park), and Yosemite were given their names by the Secretary of the Interior. Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove remained under state administration until 1906, when they were returned to federal control and incorporated in Yosemite National Park. In the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, Congress authorized U.S. Presidents to proclaim permanent forest reserves on the public domain. Forest reserves were retitled national forests in 1907, to be managed for long-term economic productivity under multiple-use conservation principles. Within 16 years Presidents Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed 159 national forests comprising more than 150 million acres. William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson added another 26 million acres by 1916. National parks, preserved largely for their aesthetic qualities, demonstrated a greater willingness to forego economic gain. Congress thus maintained direct control over the establishment of parks and frequently had to be assured that the lands in question were worthless for other purposes. Park bills were usually enacted only after long and vigorous campaigns by their supporters. Such campaigns were not driven solely by preservationist ideals: as with Yellowstone, western railroads regularly lobbied for the early parks and built grand rustic hotels in them to boost their passenger business. Mount Rainier National Park in Washington was the next of its kind, reserved in 1899. Nine more parks were established through 1916, including such scenic gems as Crater Lake in Oregon, Glacier in Montana, Rocky Mountain in Colorado, and Hawaii in the Hawaiian Islands. There were as yet no clear standards for national parks, however, and a few suffered by comparison. Among them was Sullys Hill, an undistinguished tract in North Dakota that was later transferred to the Agriculture Department as a game preserve. The Secretary of the Interior was supposed to preserve and protect the parks, but early depredations by poachers and vandals at Yellowstone revealed the difficulties to be faced in managing these remote areas. In 1883 Congress authorized him to call on the Secretary of War for assistance, and three years later he did so, obtaining a cavalry detail to enforce Yellowstone's regulations and army engineers to develop park roads and buildings. Although the military presence was extended to Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite in 1891, the later parks received civilian superintendents and rangers. National Monuments While the early national parks were being established, a separate movement arose to protect the prehistoric cliff dwellings, pueblo remains, and early missions found by cowboys, army officers, ethnologists, and other explorers on the vast public lands of the Southwest. Efforts to secure protective legislation began among historically minded scientists and civic leaders in Boston and spread to similar circles in other cities during the 1880s and 1890s. Congress took a first step in this direction in 1889 by authorizing the President to reserve from settlement or sale the land in Arizona containing the massive Casa Grande site. President Benjamin Harrison ordered the Casa Grande Ruin Reservation three years later. In 1904, at the request of the Interior Department's General Land Office, archeologist Edgar Lee Hewett reviewed prehistoric features on federal lands in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah and recommended specific sites for protection. The following year he drafted general legislation for the purpose. Strongly supported by Rep. John F. Lacey of Iowa, chairman of the House Public Lands Committee, it passed Congress and received President Theodore Roosevelt's signature on June 8, 1906. Comparable to the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, the Antiquities Act of 1906 was a blanket authority for Presidents to proclaim and reserve "historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest" on lands owned or controlled by the United States as "national monuments." It also prohibited the excavation or appropriation of antiquities on federal lands without permission from the department having jurisdiction. Separate legislation to protect the spectacular cliff dwellings of southwestern Colorado moved through Congress simultaneously, resulting in the creation of Mesa Verde National Park three weeks later. Thereafter the Antiquities Act was widely used to reserve such cultural features— and natural features as well. Roosevelt proclaimed 18 national monuments before leaving office in March 1909, 12 of which fell in the latter category. The first was Devils Tower in northeastern Wyoming, a massive stone shaft of volcanic origin, proclaimed September 24, 1906. The next three monuments followed that December: El Morro in New Mexico, site of prehistoric petroglyphs and historic inscriptions left by Spanish explorers and American pioneers; Montezuma Castle in Arizona, a well-preserved cliff dwelling; and Petrified Forest in Arizona. National monuments were proclaimed on lands administered by the Agriculture and War departments as well as Interior. Proclamations before 1933 entailed no change of administration; a monument reserved under Agriculture or War would normally remain there unless Congress later made it or included it in a national park. In 1908, broadly construing the Antiquities Act's provision for "objects of scientific interest," Roosevelt proclaimed part of Arizona's Grand Canyon a national monument. Because the monument lay within a national forest, the Agriculture Department's Forest Service retained jurisdiction until 1919, when Congress established a larger Grand Canyon National Park in its place and assigned management responsibility to Interior's National Park Service. Similarly, Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone national monuments in California, proclaimed in 1907 under Forest Service jurisdiction, moved to Interior in 1916 when Lassen Volcanic National Park was established and encompassed both areas. By the beginning of the 21st century, U.S. Presidents had proclaimed more than 100 national monuments. Although many were later incorporated in national parks or otherwise redesignated, and several were abolished, it may be said that nearly a quarter of the units of today's System sprang in whole or part from the Antiquities Act. Mineral Springs Two mineral spring reservations also contributed to the emerging National Park System. The first preceded all other components of the System outside the Nation's Capital. "Taking the cure" at mineral spring resorts became highly fashionable in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, when thousands visited such famous spas as Bath, Aix-les-Bains, Aachen, Baden-Baden, and Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary). As mineral springs were found in America, they too attracted attention. Places like Saratoga Springs in New York and White Sulphur Springs in Virginia (now West Virginia) were developed privately, but Congress acted to maintain federal control of two springs west of the Mississippi. Hot Springs in Arkansas Territory comprised 47 springs of salubrious repute emerging from a fault at the base of a mountain. In 1832 Congress reserved four sections of land containing Hot Springs "for the future disposal of the United States." After the Civil War the Interior Department permitted private entrepreneurs to build and operate bathhouses to which the spring waters were piped, and the Hot Springs Reservation became a popular resort. In 1902 the Federal Government purchased 32 mineral springs near Sulphur, Oklahoma Territory, from the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations to create the Sulphur Springs Reservation, also under Interior's jurisdiction. The reservation was enlarged in 1904, and two years later Congress renamed it Piatt National Park after the recently deceased Sen. Orville Piatt of Connecticut, who had been active in Indian affairs. Congress redesignated Hot Springs Reservation a national park in 1921. Although the park encompassed some natural terrain, it remained more an urbanized spa than a natural area. Piatt, an equally anomalous national park, lost that designation in 1976 when it was incorporated in the new Chickasaw National Recreation Area.

Interior Department Park Origins Through 1916

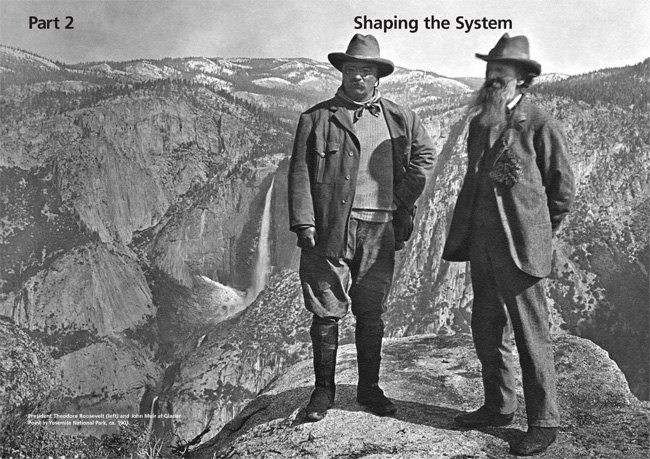

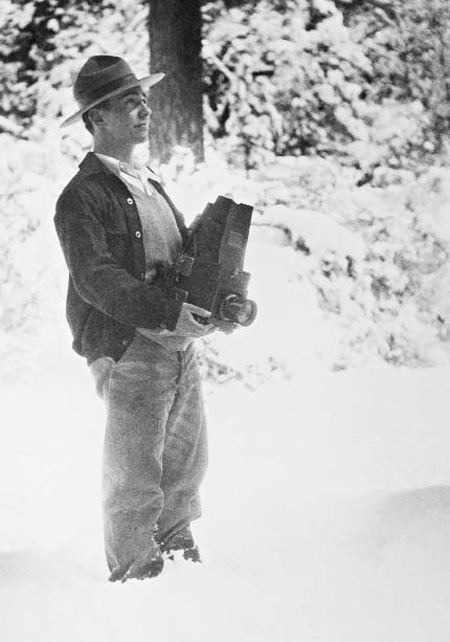

Forging a System, 1916 to 1933 By August 1916 the Department of the Interior oversaw 14 national parks, 21 national monuments, and the Hot Springs and Casa Grande Ruin reservations. This collection of areas was not a true park system, however, for it lacked systematic management. Without an organization equipped for the purpose, Interior Secretaries had been forced to call on the Army to develop and police Yellowstone and the parks in California. The troops protected these areas and served their visitors well for the most part, but their primary mission lay elsewhere, and their continued presence could not be counted on. Civilian appointees of varying capabilities managed the other national parks, while most of the national monuments received minimal attention from part-time custodians. In the absence of an effective central administration, those in charge operated with little coordinated supervision or policy guidance. Lacking unified leadership, the parks were also vulnerable to competing interests. Conservationists of the utilitarian school, who advocated the regulated use of natural resources to achieve "the greatest good for the greatest number," championed the construction of dams by public authorities for water supply, electric power, and irrigation purposes. When the city of San Francisco sought permission to dam Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park for its water supply in the first decade of the 20th century, the utilitarian and preservationist wings of the conservation movement came to blows. Over the passionate opposition of John Muir and other park supporters, Congress in 1913 approved what historian John Ise later called "the worst disaster ever to come to any national park." "The rape of Hetch Hetchy," as the preservationists termed it, highlighted the institutional weakness of the park movement. While utilitarian conservation had become well represented in government by the U.S. Geological Survey (established in 1879), the Forest Service (1905), and the Reclamation Service (1907), no comparable bureau spoke for park preservation in Washington. The need for an organization to operate the parks and advocate their interests was clearer than ever. Among those recognizing this need was Stephen T Mather, a wealthy Chicago businessman, vigorous outdoorsman, and born promoter. In 1914 Mather complained to Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane, a fellow alumnus of the University of California at Berkeley, about the mismanagement of the parks. Lane invited Mather to come to Washington and do something about it. Mather accepted the challenge, arriving early in 1915 to become assistant to the Secretary for park matters. Twenty-five-year-old Horace M. Albright, another Berkeley graduate who had recently joined the Interior Department, became Mather's top aide. Previous efforts to establish a national parks bureau in Interior had been resisted by the Agriculture Department's Forest Service, which rightly foresaw the creation and removal of more parks from its national forests. Lobbying skillfully to overcome such opposition Mather and Albright blurred the distinction between utilitarian conservation and preservation by emphasizing the economic potential of parks as tourist meccas. A vigorous public relations campaign led to supportive articles in National Geographic, The Saturday Evening Post, and other popular magazines. Mather hired his own publicist and obtained funds from 17 western railroads to produce The National Parks Portfolio, a lavishly illustrated publication sent to congressmen and other civic leaders. Congress responded as desired, and on August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson affixed his signature to the bill creating the National Park Service. The National Park Service Act made the new bureau responsible for the 35 national parks and monuments then under Interior, Hot Springs Reservation, and "such other national parks and reservations of like character as may be hereafter created by Congress." In managing these areas the NPS was directed "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." Lane appointed Mather the Service's first director. Albright served assistant director until 1919, then as superintendent of Yellowstone and field assistant director before succeeding Mather in 1929. Mather was initially incapacitated by illness, leaving Albright to organize the bureau in 1917, obtain its first appropriations from Congress, and prepare its first park policies. The policies, issued in a May 13, 1918, letter from Lane to Mather, elaborated on the Service's mission of conserving park resources and providing for their enjoyment by the public. "Every activity of the Service is subordinate to the duties imposed upon it to faithfully preserve the parks for posterity in essentially their natural state," the letter stated. At the same time, it reflected Mather and Albright's conviction that more visitors must be attracted and accommodated if the parks and the NPS were to prosper. Automobiles, not permitted in Yellowstone until 1915, were to be allowed in all parks. "Low-priced camps ... as well as comfortable and even luxurious hotels" would be provided by concessioners. Mountain climbing, horseback riding, swimming, boating, fishing, and winter sports would be encouraged, as would natural history museums, exhibits, and other activities furthering the educational value of the parks. The policy letter also sought to guide further expansion of the System: "In studying new park projects, you should seek to find scenery of supreme and distinctive quality or some natural feature so extraordinary or unique as to be of national interest and importance.... The national park system as now constituted should not be lowered in standard, dignity, and prestige by the inclusion of areas which express in less than the highest terms the particular class or kind of exhibit which they represent." The first national park following establishment of the National Park Service was Mount McKinley in Alaska, reserved in 1917 to protect the mountain sheep, caribou, moose, bears, and other wildlife on and around North America's highest mountain. The incomparable Grand Canyon National Park, incorporating the Forest Service's Grand Canyon National Monument, followed in 1919. Other national parks established through 1933 included Lafayette, Maine, in 1919 (renamed Acadia in 1929); Zion, Utah, in 1919; Utah in that state in 1924 (renamed Bryce Canyon in 1928); Grand Teton, Wyoming, in 1929; and Carlsbad Caverns, New Mexico, in 1930. Like Grand Canyon, all these except Grand Teton incorporated earlier national monuments. Casa Grande Ruin Reservation remained under Interior's General Land Office until 1918, when it was proclaimed a national monument and reassigned to the NPS. Two Alaska monuments proclaimed during the period, Katmai and Glacier Bay, were each larger than any national park and until 1978 were the System's largest areas. Katmai, established in 1918, protected the scene of a major volcanic eruption six years before. Glacier Bay, established in 1925, contained numerous tidewater glaciers and their mountain setting. Congress made both of them national parks in 1980. Badlands National Monument, South Dakota, and Arches National Monument, Utah, both established in 1929, became national parks in the 1970s. Badlands was the first national monument established directly by an act of Congress rather than by a Presidential proclamation under the Antiquities Act. By the beginning of the 21st century Congress had established more than three dozen national monuments, although about a third of them no longer retained that designation. Through the 1920s the National Park System was really a western park system. Of the Service's holdings, only Lafayette (Acadia) National Park in Maine lay east of the Mississippi. This geographic bias was hardly surprising: the West was the setting for America's most spectacular natural scenery, and most of the land there was federally owned—subject to park or monument reservation without purchase. If the System were to benefit more people and maximize its support in Congress, however, it would have to expand eastward—a foremost objective of NPS leadership. In 1926 Congress authorized Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains, and Mammoth Cave national parks in the Appalachian region but required that their lands be donated. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who gave more than S3 million for lands and roads for Acadia, contributed more than $5 million for Great Smoky Mountains and a lesser amount for Shenandoah. With such private assistance, the states involved gradually acquired and turned over the lands needed to establish these large natural parks in the following decade. But the Service's greatest opportunity in the East lay in another realm—that of history and historic sites. The War Department had been involved in preserving a range of historic battlefields, forts, and memorials there since the 1890s. Horace Albright, whose expansionist instincts were accompanied by a personal interest in history, sought the transfer of these areas to the NPS soon after its creation. He argued that the NPS was better equipped to interpret them to the public, but skeptics in the War Department and Congress questioned how the bureau's focus on western wilderness qualified it to run the military parks better than the military. After succeeding Mather as director in 1929, Albright resumed his efforts. As a first step he got Congress to establish three new historical parks in the East under NPS administration: George Washington Birthplace National Monument at Wakefield, Virginia; Colonial National Monument at Jamestown and Yorktown, Virginia; and Morristown National Historical Park in New Jersey, where Washington and the Continental Army spent two winters during the Revolution. Morristown, authorized March 2, 1933, was the first national historical park, a more descriptive designation that Congress would apply to Colonial in 1936 and three dozen more historical areas thereafter. Of more immediate significance, Colonial's Yorktown Battlefield and Morristown moved the NPS directly into military history, advancing its case for the War Department's areas. They would not be long in coming.

National Park System Additions 1917-1933

The Reorganization of 1933 On March 3, 1933, President Herbert Hoover approved legislation authorizing Presidents to reorganize the executive branch of the government. He had no time to take advantage of the new authority, for he would leave office the next day. The beneficiary was his successor Franklin D. Roosevelt. Hoover had arranged to give the government his fishing retreat on the Rapidan River in Virginia for inclusion in Shenandoah National Park. On April 9 Roosevelt motored there to inspect the property for his possible use. Horace Albright accompanied the party and was / invited to sit behind the President on the return drive. As they passed through Civil War country, Albright turned the conversation to history and mentioned his desire to acquire the War Department's historical^ areas. Roosevelt readily agreed and directed him to initiate an executive order for the transfer. Roosevelt's order — actually two orders signed June 10 and July 28, effective August 10 — did what Albright had asked and more. Not only did the National Park Service receive the War Department's parks and monuments, it achieved another longtime objective by getting the national monuments then held by the Forest Service and responsibility for virtually all monuments created thereafter until the 1990s. It also took over the National Capital Parks, then managed by a separate office in Washington. When the dust settled, the Service's previous holdings had been joined by a dozen predominantly natural areas in eight western states and the District of Columbia and 44 historical areas in the District and 18 states, 13 of them east of the Mississippi. The reorganization of August 10, 1933, was arguably the most significant event in the evolution of the National Park System. There was now a single system of federal parklands, truly national in scope, embracing historic as well as natural places. The Service's major involvement with historic sites held limitless potential for the System's further growth. Unlike the War Department, the NPS was not constrained to focus on military history but could seek areas representing all aspects of America's past. Management of the parks in the Nation's Capital would give the NPS high visibility with members of Congress and visitors from around the Nation and invite expansion of the System into other urban regions. Although the big western wilderness parks would still dominate, the bureau and its responsibilities would henceforth be far more diverse. National Capital Parks The parks of the Nation's Capital are the oldest elements of today's National Park System, dating from the creation of the District of Columbia in 1790-91. On July 16, 1790, President George Washington approved legislation empowering him to appoint three commissioners to lay out the District, "purchase or accept such quantity of land ... as the President shall deem proper for the use of the United States," and provide suitable buildings for Congress, the President, and government offices. The next year Washington met with the proprietors of lands to be included in the federal city and signed a purchase agreement resulting in the acquisition of 17 reservations. In accordance with Pierre Charles L'Enfant's plan for the city, Reservation 1 became the site of the White House and the President's Park, including Lafayette Park and the Ellipse; Reservation 2 became the site of the Capitol and the Mall; and Reservation 3 became the site of the Washington Monument. A century later the Nation's Capital park system received two major additions. Rock Creek Park, Washington's largest, was authorized by Congress on September 27, 1890 — two days after Sequoia and four days before Yosemite. Some of the same legislative language that the California parks inherited from Yellowstone appeared in this act as well. Rock Creek Park was "dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasure ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United States," and regulations were ordered to "provide for the preservation from injury or spoliation of all timber, animals, or curiosities within said park, and their retention in their natural condition, as nearly as possible." Its value as a preserved natural area increased with the growth of its urban environs (although the NPS has magnified its significance since 1975 by listing the park with its California contemporaries as a discrete National Park System unit). East and West Potomac parks, on the other hand, were artificially created on fill dredged from the Potomac River in the 1880s. In 1897 Congress reserved this large reclaimed area for park development, and in the 20th century it became the site of the Lincoln, Jefferson, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorials; Constitution Gardens; and the Vietnam Veterans and Korean War Veterans memorials, among other features. The last major addition to the Nation's Capital park system before the reorganization was the George Washington Memorial Parkway. A 1928 act of Congress authorized the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway, linking the planned Arlington Memorial Bridge and Mount Vernon, to be completed for the bicentennial of Washington's birth in 1932. In 1930 Congress incorporated the highway in a greatly enlarged George Washington Memorial Parkway project, which entailed extensive land acquisition and scenic roadways on both sides of the Potomac River from Mount Vernon upstream to Great Falls. Although never fully completed as planned, the project proceeded far enough by the 1960s to buffer significant stretches of the river with parkland. The parks of the Nation's Capital were managed by a succession of administrators, beginning with the commissioners appointed by President Washington to establish the federal city. From 1802 to 1867 the city's public buildings and grounds were under a superintendent and then a commissioner of public buildings, who reported to the Secretary of the Interior after the Interior Department was established in 1849. In 1867 the parks and buildings were turned over to the chief engineer of the Army. His Office of Public Buildings and Grounds ran them until 1925, when it was succeeded by the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital. The latter office, still headed by an army engineer officer but directly under the President, lasted until the 1933 reorganization. Its responsibility for federal buildings as well as parks passed to the National Park Service, which was renamed the Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations in Roosevelt's executive orders. The bureau carried this unwieldy title for less than seven months, regaining its old name in a March 2, 1934, appropriations act; but it did not shed the public buildings function until 1939. The term National Capital Parks (usually capitalized) has been variously used since the reorganization as a collective designation for the national parklands in and around Washington and as the name of the NPS office managing them. Today National Capital Parks officially denotes only those miscellaneous parklands in the District of Columbia and nearby Maryland not classed as discrete units of the National Park System. The designation thus excludes the major Presidential and war memorials and certain other NPS-administered properties in the Washington area. But it is often used informally to encompass them as well. National Memorials National memorials in and outside Washington formed the most distinctly different class of areas added in the reorganization. Among them are such great national symbols as the Washington Monument and the Statue of Liberty. Although these and several other National Park System memorials bear other designations, they qualify as memorials because they were not directly associated with the people or events they commemorate but were built by later generations. The first federal action toward a national memorial now in the System came in 1783, when the Continental Congress resolved "that an equestrian statue of General Washington be erected where the residence of Congress shall be established." L'Enfant's plan for the city of Washington provided a prominent location for the statue, but Congress provided no funds for it. A private organization, the Washington National Monument Society, acquired the site and began construction of an obelisk in 1848, but its resources proved inadequate. Not until 1876, the centennial of American independence, did the government assume responsibility for completing and maintaining the Washington Monument. Army engineers finished it in accordance with a simplified design, and it was dedicated in 1885. During the centennial France offered the Statue of Liberty as a gift to the United States. Congress authorized acceptance of the statue, provision of a suitable site in New York Harbor, and preservation of the structure "as a monument of art and the continued good will of the great nation which aided us in our struggle for freedom." In effect a memorial to the Franco-American alliance during the Revolution, the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886. President Calvin Coolidge proclaimed it a national monument under the War Department, its custodian, in 1924. In 1911 Congress authorized construction of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington's Potomac Park, directly aligned with the Capitol and the Washington Monument. The completed masterpiece of architect Henry Bacon and sculptor Daniel Chester French was dedicated in 1922. Another classical memorial to Lincoln, enshrining his supposed birthplace cabin at Hodgenville, Kentucky, had been privately erected in 1907-11 from a design by John Russell Pope, architect of the later Thomas Jefferson Memorial in Washington. The birthplace property was given to the United States in 1916 and administered by the War Department as Abraham Lincoln National Park. It was ultimately redesignated a national historic site after it came under the National Park Service, but the character of its development makes it in effect a memorial. Other memorials authorized by Congress before 1933 included one to Portuguese explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in San Diego, proclaimed Cabrillo National Monument under the War Department in 1913; Perry's Victory Memorial, Ohio, in 1919; Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota, in 1925; Kill Devil Hill Monument (later Wright Brothers National Memorial), North Carolina, in 1927; the George Rogers Clark Memorial in Vincennes, Indiana, in 1928; and Theodore Roosevelt Island in Washington, D.C., in 1932. Cabrillo National Monument and Kill Devil Hill Monument were transferred from the War Department and Theodore Roosevelt Island from the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital in the reorganization, which also gave the NPS fiscal responsibility for the commissions developing the Mount Rushmore and George Rogers Clark memorials. The NPS received Mount Rushmore itself in 1939 and the Clark memorial under a 1966 act of Congress authorizing George Rogers Clark National Historical Park. Several historic sites proposed for this park were never acquired, leaving it essentially a memorial area. The NPS had no responsibility for Perry's Victory Memorial, constructed by another commission, until 1936, when Congress authorized its addition to the National Park System as Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial National Monument. The superfluous national monument suffix was dropped in 1972. The Lee Mansion in Arlington, Virginia, transferred from the War Department in the reorganization, was ultimately retitled Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, by Congress in 1972. (Because the house was directly associated with Lee and has been restored to the period of his occupancy, it would more appropriately be designated a national historic site.) National Battlefields and Cemeteries The first official step to commemorate an American battle where it occurred was taken in 1781. Inspired by the Franco-American victory over the British at Yorktown that October, the Continental Congress authorized "to be erected at York, Virginia, a marble column, adorned with emblems of the alliance between the United States and His Most Christian Majesty; and inscribed with a succinct narrative of the surrender." Funds were then unavailable, and Congress did not follow through until the centennial of the surrender in 1881, when the Yorktown Column was raised as prescribed a century before. It is now a prominent feature of Colonial National Historical Park. The battlefield monument idea received major impetus in 1823 when Daniel Webster, Edward Everett, and other prominent citizens formed the Bunker Hill Battle Monument Association to save part of Breed's Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, and erect a great obelisk on it. Webster delivered a moving oration before a large audience at the cornerstone laying in 1825, the 50th anniversary of the battle. The Bunker Hill Monument demonstrated how commemorative sentiment might be crystallized and was the prototype for many other battlefield monuments. During the centennial years of the Revolution, Congress appropriated funds to supplement local contributions for monuments at Bennington Battlefield, Saratoga, Newburgh, and Oriskany, New York; Kings Mountain, South Carolina; Monmouth, New Jersey; and Groton, Connecticut. Like the Yorktown Column, the Bunker Hill, Kings Mountain, and Saratoga monuments were later included in National Park System areas. The "mystic chords of memory" elicited by such Revolutionary War monuments in both the North and the South helped draw the two sections together after the Civil War. Confederate veterans from South Carolina and Virginia participated in the Bunker Hill centennial in 1875, the first time former Union and Confederate troops publicly fraternized after the war. The practice of joint reunions later spread to Civil War battlefields, culminating in huge veterans' encampments at Gettysburg in 1888 and Chickamauga in 1889. Even before the Civil War ended, Pennsylvania had chartered the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association in 1864 to commemorate "the great deeds of valor . . . and the signal events which render these battle-grounds illustrious." A preservation society also began work at Chickamauga, Georgia, and Chattanooga, Tennessee. Prompted by veterans' organizations and others influential in such activities, Congress began in the 1890s to go beyond the battlefield monument concept to full-scale battlefield preservation. On August 19, 1890, a month before establishing Sequoia National Park, Congress authorized Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park. Three more national military parks followed before the century's end: Shiloh in 1894, Gettysburg in 1895, and Vicksburg in 1899. The War Department purchased and managed their lands, while participating states, military units, and associations provided monuments at appropriate locations. At Antietam, on the other hand, Congress provided for acquisition of only token lands where monuments and markers might be placed. It and other places where this less expansive policy was adopted were designated national battlefield sites. Antietam and most of the other national battlefield sites were later enlarged and retitled national battlefields. The 1907 authorization of the Chalmette Monument and Grounds, commemorating the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, departed from the recent focus on the Civil War. Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, North Carolina, authorized a decade later, encompassed the first Revolutionary War battlefield so preserved. Confronted with many more proposals, Congress in 1926 asked the War Department to survey all the nation's historic battlefields and make recommendations for their preservation or commemoration. The results guided Congress in adding 11 more areas to the War Department's park system before the reorganization: the site of the opening engagement of the French and Indian War at Fort Necessity in Pennsylvania; the Revolutionary War battlefields of Cowpens and Kings Mountain in South Carolina and Moores Creek in North Carolina; and the Civil War sites of Appomattox Court House, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County, and Petersburg in Virginia, Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo in Mississippi, and Fort Donelson and Stones River in Tennessee. Roosevelt's initial executive order of June 10, 1933, had provided for all the War Department's domestic national cemeteries to come to the NPS along with its battlefield parks. At Horace Albright's urging, this wholesale transfer was amended in the supplementary order of July 28 to include only 11 cemeteries associated with the battlefields or other NPS holdings: Antietam (Sharpsburg) National Cemetery, Maryland; Battleground National Cemetery, Washington, D.C.; Chattanooga National Cemetery, Tennessee (returned to the War Department in 1944); Fort Donelson (Dover) National Cemetery, Tennessee; Fredericksburg National Cemetery, Virginia; Gettysburg National Cemetery, Pennsylvania; Poplar Grove (Petersburg) National Cemetery, Virginia; Shiloh (Pittsburgh Landing) National Cemetery, Tennessee; Stones River (Murfreesboro) National Cemetery, Tennessee; Vicksburg National Cemetery, Mississippi; and Yorktown National Cemetery, Virginia. Most famous among these is Gettysburg National Cemetery. The battle of Gettysburg was scarcely over when Gov. Andrew Y. Curtin of Pennsylvania hastened to the field to help care for the casualties. More than 3,500 Union soldiers had been killed in action; many were hastily interred in improvised graves. At Curtin's request, Gettysburg attorney David Wills purchased 17 acres and engaged William Saunders, an eminent horticulturalist, to lay out the grounds for a cemetery. Fourteen northern states provided the necessary funds. At the dedication on November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address. Gettysburg National Cemetery became the property of the United States in 1872, 23 years before establishment of the adjoining national military park. Similar events took place on the other great battlefields of the Civil War. Congress recognized the importance of caring for the remains of the Union war dead with general legislation in 1867 enabling the extensive national cemetery system developed by the War Department. As at Gettysburg, each of the battlefield cemeteries was carefully landscaped to achieve an effect of "simple grandeur," and each preceded establishment of its related battlefield park. The 1867 act also led to preservation of an important battleground of the Indian wars. In 1879 the Secretary of War established a national cemetery on the Little Bighorn battlefield in Montana Territory, and in 1886 President Grover Cleveland reserved a square mile of the battlefield for what was then called the National Cemetery of Custer's Battlefield Reservation. The War Department transferred the reservation to the NPS in 1940. Congress retitled it Custer Battlefield National Monument in 1946 and Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in 1991. (To retain some titular recognition of Custer, the 1991 act also designated the cemetery within the monument Custer National Cemetery.) Other national cemeteries acquired by the NPS after the reorganization were Andrew Johnson National Cemetery, part of Andrew Johnson National Monument, Tennessee, authorized in 1935; Chalmette National Cemetery, transferred from the War Department for Chalmette National Historical Park, Louisiana, in 1939; and Andersonville National Cemetery, part of Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia, authorized in 1970. Until 1975 the national cemeteries acquired in the reorganization were listed as separate units of the National Park System. Since then the cemeteries, while retaining their special identities, have been carried as components of their associated parks. Other War Department Properties As national monuments were being reserved under Interior Department jurisdiction, others were proclaimed on War and Agriculture department lands. Ten national monuments were on military reservations before their transfer to the NPS in 1933. President William Howard Taft proclaimed the first War Department national monument, Big Hole Battlefield, Montana, in 1910 to protect the site of an 1877 battle between U.S. troops and Nez Perce Indians. Five later monuments resulted from a single proclamation by President Coolidge on October 15, 1924. Fort Marion National Monument, later retitled with its Spanish name Castillo de San Marcos, recognized an old Spanish fort in St. Augustine, Florida. Fort Matanzas National Monument protected an outpost built by the Spanish in 1742 to defend the southern approaches to St. Augustine. Fort Pulaski National Monument contained a brick fort built during the 1830s outside Savannah that had yielded under bombardment by Federal rifled cannon in 1862. The Statue of Liberty, based on Fort Wood in New York Harbor, became a national monument (to which Ellis Island was added in 1965). A small national monument for Castle Pinckney in Charleston Harbor was later abolished. Two War Department areas acquired in the reorganization were then titled national parks. Abraham Lincoln National Park has been cited above in connection with memorials. The other was Fort McHenry in Baltimore. A 1925 act of Congress directed the Secretary of War "to begin the restoration of Fort McHenry ... to such a condition as would make it suitable for preservation permanently as a national park and perpetual national memorial shrine as the birthplace of the immortal 'Star- Spangled Banner."' Abraham Lincoln and Fort McHenry national parks received more appropriate designations after coming to the NPS, although the unique "national monument and historic shrine" label Congress gave the fort in 1939 might have been abridged. Arlington, the estate across the Potomac from Washington, D.C., was inherited by Robert E. Lee's wife from her father, George Washington Parke Custis, in 1857. During the Civil War the Union Army occupied it and the War Department began what became Arlington National Cemetery on its grounds. Lee's national reputation rose in later years, and in 1925 Congress authorized the War Department to restore Arlington House (also termed the Lee Mansion and Custis-Lee Mansion) in his honor. After the mansion's transfer to the NPS it was managed with the National Capital Parks. The 1930 act authorizing the George Washington Memorial Parkway directed that Fort Washington, a 19th-century fortification guarding the Potomac approach to the capital, should be added to the parkway holdings when no longer needed for military purposes. The War Department relinquished it to the NPS in 1940. Fort Washington Park has been classified as a separate unit of the National Park System since 1975. Agriculture Department National Monuments Twenty-one national monuments were proclaimed on national forest lands under the Department of Agriculture before the 1933 reorganization. The first two were Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone in Lassen Peak National Forest, proclaimed by Theodore Roosevelt on May 6, 1907, to protect evidence of what was then the most recent volcanic activity in the United States. As previously noted, they were transferred to the Interior Department in 1916 as the nuclei of Lassen Volcanic National Park. Fourteen of Agriculture's other monuments were also established to preserve "scientific objects." Especially noteworthy was Roosevelt's 1908 proclamation of Grand Canyon National Monument, comprising 818,650 acres within Grand Canyon National Forest, to impede commercial development there. Roosevelt's bold action was later sustained by the U.S. Supreme Court, confirming the precedent for other vast monuments like Katmai, Glacier Bay, and Death Valley. The Grand Canyon monument was superseded by Grand Canyon National Park when the latter was established under NPS jurisdiction in 1919. (A second Grand Canyon National Monument, proclaimed in 1932 and assigned to the NPS, was incorporated in the national park in 1975.) On March 2, 1909, two days before leaving office, Roosevelt proclaimed another large national monument, Mount Olympus in Olympic National Forest, Washington. Encompassing 615,000 acres, it was intended to protect the Roosevelt elk and important stands of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, Douglas fir, and Alaska cedar. It formed the nucleus for Olympic National Park in 1938. The other natural monuments included four caves: Jewel Cave in South Dakota; Oregon Caves in Oregon; Lehman Caves in Nevada; and Timpanogos Cave in Utah. In the National Park System they would join Carlsbad Caverns, Mammoth Cave, and Wind Cave national parks (and two national monuments later abolished: Lewis and Clark Caverns, Montana, and Shoshone Cavern, Wyoming). The first of only five archeological monuments in the group was Gila Cliff Dwellings, New Mexico, proclaimed November 16, 1907. It was followed by Tonto and Walnut Canyon in Arizona and then by Bandelier, New Mexico, established within the Santa Fe National Forest in 1916. President Hoover enlarged Bandelier and reassigned it to the NPS in February 1932, a year and a half before the reorganization. The fifth was Old Kasaan National Monument, Alaska, abolished in 1955. A limited reversion to Agriculture Department administration of national monuments came on December 1, 1978, when President Jimmy Carter proclaimed the Admiralty Island and Misty Fjords national monuments within Tongass National Forest, Alaska, and ordered their retention by the Forest Service. Congress confirmed their status two years later. In 1982 Congress established Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument at the site of the recent eruption in Gifford Pinchot National Forest, Washington, and kept it under the Forest Service. It did the same with Newberry National Volcanic Monument, established in 1990 in Deschutes National Forest, Oregon.

Background to the Reorganization of 1933

NPS Areas Resulting from the 1933 Reorganization

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NHS, Kentucky