CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Capitol Reef National Park

|

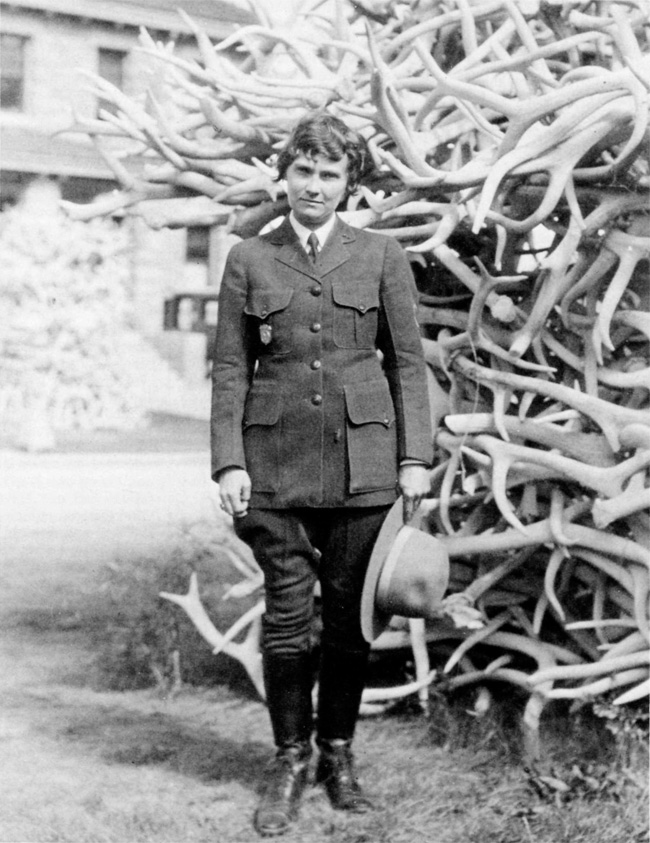

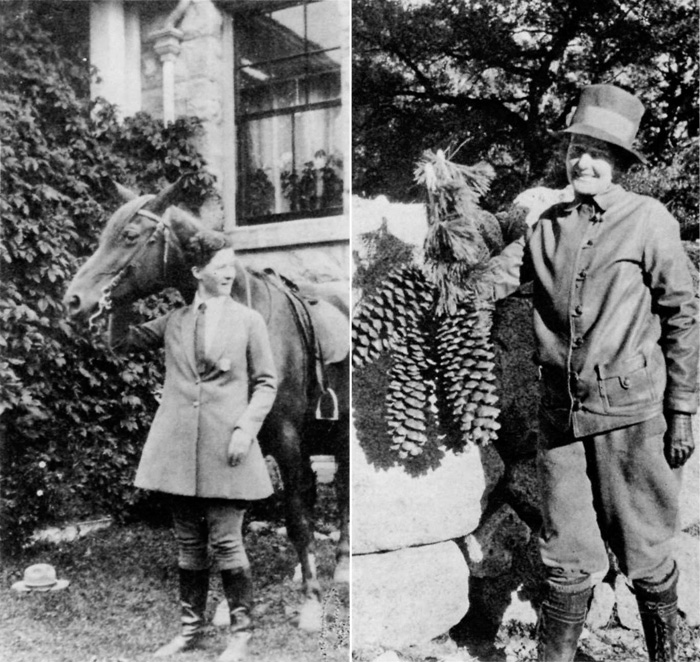

The following article first appeared in Ranger: The Journal of the Association of National Park Rangers, Vol. I, No. 4 Fall, 1985. Of related interest: Women in the Park Service, The Way We Were: Women and the National Park Service and National Park Service Wives and Women Employees Handbook. Women in the National Park ServicePolly Welts Kaufman Frieda Nelson was a bit premature in 1926 when she so proudly displayed her suspenders in her second season as a summer ranger at Yellowstone National Park. Although women like her who did achieve park ranger status before the early 1970's have gone down in Park Service history as the first women rangers, they did not bring real change to the position of women in the Service. But they did demonstrate that women could do the job, and when the movement for equal opportunity finally took hold in the Service, many Park Service people could picture women in uniform because they could recall these early women rangers. Needs in the broader society have had an enormous influence on the place of women in the Park Service. The example of the history of women rangers at Mount Rainier demonstrates in a microcosm how events outside the Service influenced opportunities for women to be rangers. In 1918, at the end of World War I, Helene Wilson was put in charge of the Nisqually Entrance Station for a season. In 1943, during World War II, Barbara Dickinson and Catherine Byrnes were given the same assignment. According to park records, it was not until 1974 that another woman, Becky Rhea, was hired as a ranger. Now at Mount Rainier the visitor has an even chance of being greeted by a woman ranger or park technician. Servicewide, a visitor will meet a woman ranger or park tech in approximately one in three contacts.

The event that impacted the most heavily on the chances for women to serve as park rangers was the wave of gratitude that swept the country when the veterans returned from World War II. It reinforced the already strong male imprint on the Park Service ranger image. In 1949, a key examination for park ranger was offered which received wide attention. Hundreds of jobs were open as the Service tried to bring order to the temporary appointments made to returning veterans. Preparation books had a brisk sale. The Arco study guide read: The Examination for Park Ranger Park Ranger Jobs for Men 21 to 35 "One of the largest nation-wide examinations is now open. The job is park ranger, at $2,974.89 a year, for duty in the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. . . . "The positions are located throughout the United States and in the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii. All nonstatus Park Rangers and Superintendents must take this examination if they wish to qualify for permanent appoint. . . . Age limits are waived for those entitled to veterans preference. . . . "Appointees must buy uniforms (cost about $150.00). "There will be hundreds of vacancies. . . ." The result is evident. Hundreds of male veterans with an advantage of either five or ten (if disabled) points and just beginning their careers entered the Park Service on a permanent basis in late 1949. Many stayed and progressed up through the ranks. Many had been serving in temporary positions since the war, and they eagerly awaited the achievement of permanent status.

Before fifteen years passed, and while these men worked their way up the organizational ladder, the Civil Rights movement was in full swing. Several events happened that affected the laws regulating the federal employment of women. A "New Era" had begun, however slowly, and the Park Service had to face change. The Commission on the Status of Women established by President Kennedy by Executive Order in 1961 highlighted in its report the pivotal role the federal government must play in the employment of women. The President directed the Civil Service Commission and agency heads to make the government, as the largest single employer of women, "a showcase of equal opportunity for women." In 1962, Attorney General Robert Kennedy invalidated an old law which allowed appointments to specify sex. That old law is interesting in itself. It dated from 1870 and was passed to allow the appointment of women to clerkships in executive departments. However, it had long been interpreted as allowing appointing officers to specify sex in filling positions. The Attorney General's ruling meant that no longer could "park ranger" examinations state that positions were for men only. The 1870 law was actually repealed in 1965, and civil service regulations were revised in 1966 to require each federal agency to establish an affirmative action program. Equal opportunity programs were put into action. Before looking at how these new regulations affected women's chances for careers in the Park Service, one other important piece of background needs to be studied — this time specific to the Park Service and concerning its historic mission rather than its employment policies and practices. The famous Organic Act establishing the Park Service in 1916 set up for all time a tension between use and preservation. Preservation was clearly the only goal in the beginning, because the first natural sites were in real danger from exploitation by developers, forest and mining interests, and adventurers. So essential was the goal of protection, in fact, that the U.S. Cavalry was used to staff Yellowstone before 1916. The ethos of a military camp pervaded the early parks, and the few women present were military wives. After the Organic Act of 1916, the ethos of the Park Service underwent a gradual change until the parks became today's centers for public education through interpretation. Although the first parks celebrated America's natural wonders, historic and cultural sites began to be added beginning with Mesa Verde in 1906, and eventually included a large number of historic forts transferred from the U.S. Army to the Park Service in the 1930's. As interpretive activities began to increase in importance (and perhaps as they became stratified), more positions became available for which mainstream women possessed the necessary qualifications. Women teachers, curators, librarians and historians held the necessary qualifications to become interpreters, especially in historic sites. In the 1950's and early 1960's, often at the same time that the male park rangers were taking their permanent positions, women were hired as guides at such places as Fort Laramie, Colonial, and Independence. The story of their uniforms has often been told. At first the guides could order regular uniforms (one woman had to make her own, because she was so small), but after a while the women guides were required to wear various kinds of polyester, airline-steward type uniforms with a similar hat, called by some of its former wearers a "baffalo chip." In fact, it was in the field of natural history interpretation that a few women had been active from the beginning. As far back as 1917, hotels in Rocky Mountain and Glacier hired women as nature guides for their guests. The Park Service employed a few interpreters directly in the 1920's, including Isobel Bassett, a geologist, who was hired on an impulse by Director Horace Albright at Yellowstone after he observed her voluntary talks on park geology, and Marguerite Lindsley, who was born in Yellowstone and married E.L. Arnold, a ranger. Herma Albertson, who passed the Civil Service test for ranger in 1919, served until she, too, married a ranger, George Baggley. She published a book on the plants in Yellowstone just as Pauline Mead Patraw, a seasonal ranger at the Grand Canyon in 1929 and 1930, did on the flowers of the Southwest mesas. At Yosemite, Enid Michael served as a naturalist for nearly twenty years. When the Park Service first began to respond to the civil rights movement, it had as much of a problem deciding what to call its new women as it did over what they were going to wear. Sallie Pierce Harris, who was a guide at Montezuma Castle in 1934, returned during World War II as a ranger, primarily at Tumacacori. Not long after the war, she learned that she could no longer be called a ranger and eventually was given the title of archeologist, the field in which she was trained. She continued with variations on that title until her retirement in the late 1960's. Indeed, the first women who were hired through the ranger intake program, beginning in 1965, were called park naturalists, historians, or information guides until 1971, when the title "park ranger" was finally attached to women. It was through the Albright Training Center that the Park Service began to recruit its first women rangers. The first two women began the Introduction to Park Operations course on an auspicious date — the day after the Fourth of July in 1965. One of them was Elaine Hounsell, who has been a superintendent of a small park and is now a district ranger at North Cascades. There were forty-one men in the class, the seventeenth to be held since its beginning in 1957. At the same time, Glennie Murray (Wall), who was doing research on the petroglyphs and pictographs at Lava Beds, was asked if she had thought of joining the Park Service. Her immediate response was: "But they don't hire women!" She was assured that "they" did and told to take the Federal Service Entrance Exam. She passed it on the first try and, as the only woman in the class, entered Albright in March, 1966. Betty Gentry was the only woman in the second 1965 class. These women are among the first full-fledged women rangers in the new era. Betty is now superintendent of Pea Ridge and Glennie the chief of the Cultural Resources Unit at Golden Gate. Except for Elaine Hounsell, who was called a park naturalist, they each first carried the title of historian. Because the environmental movement was only in the early stages, women naturalists and scientists were not being graduated from college in the numbers they are today, nor was support for women's athletics yet forthcoming. Although Title IX was enacted in 1972, the guidelines for its application to women's athletics were not released until 1979 (until the Supreme Court's Grove City decision of 1984 threatened Title IX's enforcement). Until both movements began to produce women with the necessary backgrounds, the qualifications for ranger and ranger-naturalist continued to be prohibitive for most women. Finally, late in 1969, OPM approved new classification and qualification standards to be implemented the following year. The new standards attempted to remove as many sex-specific qualifications as possible. By 1971, women trainees at Albright were called "park rangers." The effort for equity did not end there and was argued out in other positions later (the Park Police, for example, had a five foot, eight inches height restriction that was removed in 1971 only after legal action). Women began to enter the ranger training program at Albright in increasing numbers, averaging between 15 and 30 percent of the classes from 1973 until recent years, when their numbers have been approaching equity. About 375 women have graduated from the course, now called Ranger Skills, since 1965. Some of these women now hold historian or other positions. With the increasing emphasis on law enforcement training for rangers, women have been receiving training at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Glynco, Georgia, since 1975. Between 1979 and 1984, 131 Park Service women graduated from FLETC, 20 percent of the total Park Service trainees. About 40 women have taken both training programs. Other women have taken law enforcement training on their own.

Although the figures for women park rangers are not spectacular, they do show that women are here to stay. The number of women rangers can no longer be counted on the fingers of one hand as they were in 1926 when Frieda Nelson showed her pride at Yellowstone. But the numbers are small. In 1983, of nearly 2,000 park rangers, about 270 were women, or 14 percent. About 1,300 were park technicians, which was 37 percent of that series. A present study of the retention rates of women compared with men trained at each program, Albright and FLETC, should add some other figures. In 1985, at the top of the 025 series (park managers) women are superintendents in twenty-two parks and site managers of ten other parks. The highest-graded woman outside of Washington is Lorraine Mintzmyer, regional director of Rocky Mountain. An examination of the number of women at different grade levels can be interpreted in two ways. Either the percentage of women is higher at lower grades because many are just entering the Service, or women are finding if difficult to advance. Women represent one-quarter of the rangers on the GS-5 level and nearly onethird of GS-7 rangers. Beginning with GS-9, women rangers decline from 14 percent to 7 percent at GS-12 and 5 percent at GS-13. Women represent 48 percent of the GS-4 park technicians, 30 percent of the GS-5 park technicians, and 18 and 19 percent of the GS-6 and GS-7 park techs. Park aides were not counted. There is some concern that the classification of park technician, often used for interpreters, will be a way, whether conciously or not, of holding women back. Not only is it useful to put the growth of women in the ranger ranks in historical perspective, it is also important to put the roles women have played in the Park Service in the context of the roles women have filled in the broader society. Although women have only entered the ranger profession in recent years, it is important to realize that, like women everywhere, they have contributed a great deal. For that reason, the study of the history of women in the Park Service that I am currently researching will look not only at visible, permanent women. Even though they were not compensated for it, many women have made large contributions to the parks by working behind the scenes. Wives manned telephones when their husbands were on patrol, handled emergencies, started the first natural history museums in parks, wrote nature guides, and provided (and still do) support for families in isolated places as nurses and teachers. Aileen Nusbaum, for example, designed many park buildings and started the first medical facility at Mesa Verde. Wives and "homesteaders" on clerical staffs have done a great deal to weave the fabric of relations between the park and community. Another interesting group is comprised of the women who founded parks. The Colorado Cliff Dwellers Association was a women's group who worked to save Mesa Verde. Women reconstructed the Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace in New York City, and were responsible for the acquisition and restoration of Eleanor Roosevelt's Valkill. Minerva Hoyt organized the Deserts Conservation League for the purpose of saving the lands now comprising Joshua Tree, and, by working to protect Royal Palm State Park, Mary Mann Jennings provided the nucleus for the Everglades. Such women as Margaret Murie and Celia Hunter have worked for park lands, most recently in Alaska. Finally, it is important to look at how women's roles are presented in parks. The story of a single woman homesteader, Adaline Hornbek, adds to the interpretation at Florissant Fossil Beds. Diaries of officer's wives revealed the information for the furnishings at Fort Laramie, where a woman ghost also rides. The Mill girls at Lowell and the wives who brought homes to their marriages at John Muir, Martin Luther King, and Carl Sandburg all matter. The new parks devoted to women's history include Maggie Walker, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Women's Rights. Frieda Nelson had many things to be proud of as a Park Service woman. She was a ranger on horseback — at least for two seasons — and represented what women can do. Women have been working for the parks from the very beginning, when the first women explorers rode sidesaddle into Yellowstone one hundred years ago. They have served both behind the scenes and one the front line and their many stories need to be told. | ||||