CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Fort Pulaski National Monument

|

NPS Centennial Monthly Feature

For the remainder of this centennial year, we'll now explore some of the job functions which the National Park Service performs. This month and next we'll take a look at the iconic National Park Ranger. Bob Krumenaker, in article which appeared in Vol. XVI No. 2, Spring 2000 of Ranger: The Journal of the Association of National Park Rangers, asked: "What is a National Park Ranger?"

While noted for wearing their Stetson hats, the park rangers actually wear many hats, especially for smaller parks where staffing is limited and a park ranger is called on to perform several duties. Our definition of a park ranger includes these four principal functions:

The National Park Service's Learning and Development Office operates three park ranger Training Centers. The Horace Albright Training Center (Grand Canyon NP) is a primary training facility for Servicewide Employee Learning and Development. Assigned programs include the NPS Fundamentals program and Natural Resource Stewardship. The Stephen T. Mather Training Center (Harpers Ferry, WV) develops and hosts training programs and learning opportunities for a large segment of the NPS workforce. From this facility, the NPS Career Academy program, the NPS Distance Learning Center, and the Dept. of Interior Learn program are directed by training and program managers. The Historic Preservation Training Center (HPTC) (Frederick, MD) is dedicated to the safe preservation and maintenance of national parks or partner facilities by demonstrating outstanding leadership, delivering quality preservation services, and developing educational courses that fulfill the competency requirements of Service employees in the career fields of Historic Preservation Skills, Risk Management, Maintenance, and Planning, Design, and Construction. This month we recognize the role of the law enforcement ranger. For more information about park rangers, the Association of National Park Rangers is a non-profit organization dedicated "to promot(ing) and enhanc(ing) the professions, spirit and mission of National Park Service employees"; most of the issues of their excellent journal Ranger: The Journal of the Association of National Park Rangers, are online. To learn more about becoming a park ranger, Park Ranger EDU is a helpful resource to consult along with these additional books. The following article first appeared in Ranger: The Journal of the Association of National Park Rangers, Vol. I, No. 2 Spring, 1985.  The Evolution of Enforcement in the Service

The Evolution of Enforcement in the Service

William O. Dwyer and Robert Howell "To conserve the scenery and the natural and historical objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."(1) This encompassing statement articulates the double mission fundamental to the National Park Service — on the one hand it must protect the resources which have been entrusted to it and on the other it must manage the people who come, for whatever reasons, to visit the resources. Unlike some organizations which operate in fairly static environments, the Park Service is faced with the task of continually adjusting to the ever-changing demands and expectations placed on it by economics, politics and the millions of people who visit its areas each year.

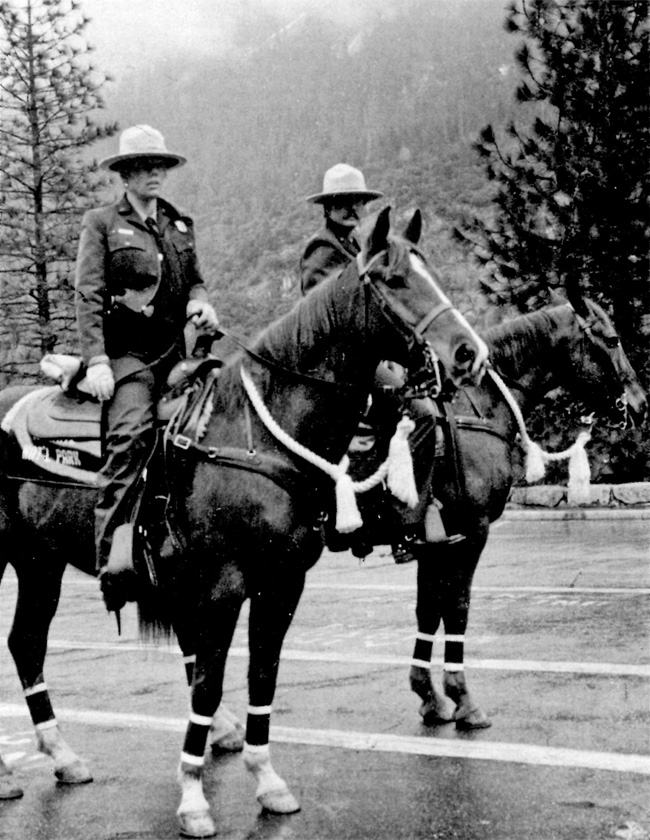

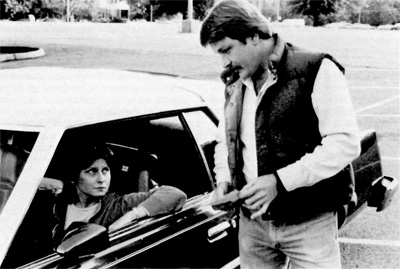

In recent years part of this burden was clearly evident in the evolution of the law enforcement role of the park ranger, during which the Park Service had to meet a perceived need to pay more attention it its law enforcement and people-management responsibilities, while at the same time preserving what was held to be the traditional role of the park ranger as an ambassador of good will. The history of this changing role is charged with strong, yet varying opinions, heated debates, false starts and many trips back to the drawing boards. It is a story of organizational change and, in our judgment, one of successful change. What happened during this period of transition? How did the Park Service deal with these changes? What pressures had to be contended with and what balances had to be reached? Parts of this story are known to many in the Service, but few — particularly among those new to the agency — have heard it in its entirety. Because of this and because much of the dust has now settled on the law enforcement question, we feel that this is a proper time and place to examine how the Service developed a law enforcement capability to meet the new demands placed on it. Historically, park rangers have been responsible for the protection of park areas even before they were officially called "rangers" in 1905(2), and it is possible to trace the evolution of law enforcement functions in the Park Service back- to its inception. However, significant changes in the ranger's law enforcement role did not begin to take place until the late 1960s. The 1960s and early 1970s witnessed the advent of the national recreation areas and national seashores and lakeshores, many of which were near urban locations and were developed with extensive visitor use in mind. The introduction of these areas modified rangers' responsibilities and oriented them toward the visitors and their behavior, in contrast to the resourceprotection emphasis they had traditionally known. People were beginning to make much greater use of park areas, and with these people came a need to manage them effectively. In 1970 the International Association of Chiefs of Police completed a study for the Park Service which revealed that an increasing burden was being placed on the park ranger in the area of people management and law enforcement. The report stated that this burden stemmed from the "growth in public use in national parks and the growing tendency to disregard park regulations and the rights of others. "(3) A major incident supporting the findings of this study occurred in Yosemite in July 1970. Several hundred young people gathered in Stoneman's Meadow and drew complaints of "dope, profanity, nudity and sex" from other park visitors. After this group ignored a curfew, rangers on horseback drove them from the meadow, but the following day the group returned and this time the rangers were met with bottles and rocks.(4) In the hours that followed, nearly 100 police officers from nearby communities assisted the rangers in quelling the disturbance. Numerous people were arrested and several accusations were made concerning the use of excessive force by police and rangers. (5) Referring to this incident two years later, then Assistant Director William C. Everhart wrote, "The rangers, including a number of seasonal employees, were desperately trying to handle a situtaion for which they were ill equipped by reason of training, equipment and ideology. Should another disturbance occur, however, it will be treated differently. "(6) In spite of this clear demonstration of the need to reassess the role law enforcement should be playing in the Park Service and the training and authority park rangers should be given to become effective people managers, these developments would be slow in coming as the Service attempted to structure these changes and avoid the possibility of an independent "police" subculture evolving within the ranger ranks.

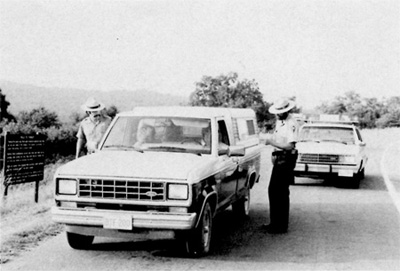

Throughout the history of the Park Service the image of the ranger had been that of a dedicated naturalist or historian protecting a treasured resource and providing services to the public. This image was accepted by the rangers, the Park Service and by the public as a whole. A metamorphosis of the ranger's role to include police training and functions would be threatening to many within the system and any changes would have to produce a minimal impact on this positive ranger image in order to be accepted. In spite of the general trepidation about a "police" subculture, it was clear to many that change would have to take place. As noted in a 1970 survey conducted by the U. S. Park Police, "...if we do not deal effectively with this problem (violators annoying visitors) the camper who brings his family may be persuaded not to visit the National Parks...."(7) The same survey noted that the Park Service had not recruited personnel who had the training or desire to engage in law enforcement and that many who were already in the service did not want to accept the role of "cops" in the parks. These were rangers who were ill equipped by reason of "ideology" to whom Assistant Director Everhart had referred. Thus, the seeds of resistance to change were already apparent. In order to accomplish its expanding people management function, the Park Service had to overcome three major problems: There was a lack of clear statutory authority, law enforcement guidelines, and standards of behavior; there was a general reticence to make a greater law enforcement role part of the park ranger's responsibilities; and, if and when this greater role evolved, it had to be prevented from dominating the park ranger's total identity. Changes in Statutory Authority Prior to 1976, the statutory authority allowing rangers to enforce regulations in Park Service areas was very vague and did not give expressed permission to carry firearms or make arrests for federal crimes.(8) The most significant change in Park Service law enforcement authority to date came in the form of Congressional action signed into law in 1976. Public Law 94-458 (16 USC, Section la) was known as the "General Authorities Act"; it clearly established the power of the Secretary of the Interior to designate certain employees to "maintain law and order and to protect persons and property within the areas of the National Park system."(9) For the first time certain park employees (i.e., rangers) were authorized to carry firearms, make arrests, serve warrants, and conduct investigations in the absence of, or in cooperation with, other federal law enforcement agencies. The General Authorities Act also laid to rest a movement which surfaced during this period when the ranger's role was under transition. Many in the Park Service felt that police tasks could be contracted out to local law enforcement agencies. By having police and sheriff's deputies patrol the parks, it would enable the rangers to engage in traditional ranger activities, to manage the resources and preserve their friendly image among the visitors. Strong feelings arose both for and against the contract law enforcement notion, but the issue was resolved by the General Authorities Act; it mandated that the Park Service "...shall not authorize the delegation of law enforcement responsibilities of the agency to State and local governments..." except to supplement rangers in cases of emergencies. Still others believed that the traditional social ambassador role of the park ranger could be preserved by expanding the U. S. Park Police and giving them primary responsibility for law enforcement in the parks.(10) With the implementation of the General Authorities Act and the changing role of the park ranger, this movement, like contract law enforcement, would never become a reality. Although Public Law 94-458 clearly established a law enforcement role for park rangers, the legislators who enacted it were sensitive to the general concern that the new authority might pave the way for the development of a "police" subculture within the park system. In the House Report accompanying the act, Congress was very clear in its intent that the new law enforcement responsibilities were not to encompass the total activities of park rangers; rather, they were to engage in law enforcement only in conjunction with their other traditional responsibilities.(11) This Congressional caveat also reflected the central theme of the Park Service in its effort to develop and adjust to a law enforcement function which the times had mandated. The Law Enforcement Subculture With the passage of the General Authorities Act, renewed concern developed in the Park Service over the impact of the law enforcement role on the park ranger. Lines were drawn between those who welcomed law enforcement as a tool for managing people in the parks and those were were concerned about the possibility of the new authority nurturing a "police image" among rangers. This feeling that law enforcement duties could interfere with the other ranger functions was expressed by then Director Gary Everhardt in 1976 in a memorandum stating that he believed some parks had let their law enforcement activites get out of balance with other ranger functions. Everhardt stressed the importance of adequate law enforcement without detracting from other traditional visitor services.(12) Conversely, others saw the new authority as a definition of the role the ranger was to play in the protection of parks and their visitors. In a number of parks (especially those with exclusive and concurrent jurisdiction) rangers had been required to enforce laws with vague authority and with little assistance from local police agencies.(13) Many of these rangers welcomed the clear authority to deal with the "increasing criminal activity on visitor-oriented federal lands."(14) Some parks were beginning to experience the same types of crimes that had plagued only urban areas in the past, and in some areas a sense of urgency was developing that positive steps should be taken to deal with the problem. During this period the name Ken Patrick was central to any discussion of the problems of crime in the parks. While making a traffic stop, ranger Patrick was shot to death in 1973 by a felon at Point Reyes National Seashore.(15) The Gun Issue It is certainly true that this type of crime in the national park system was not commonplace and that rangers enforcing regulations are rarely in fear for their lives, but the incident did present a strong argument for insuring that rangers were adequately trained and equipped to deal with the most dangerous situations. Nonetheless, in the years that followed Patrick's death, the debate over the appropriate law enforcement role for the ranger continued to grow. One of the focal points for this debate centered around the issue of wearing sidearms; the gun became the symbol for people on both sides of the debate. In June 1975 Chester Brooks, then Mid-Atlantic regional director, issued a memorandum asking all park superintendents in the region to submit a "list of justifications wherein it is essential for employees to wear sidearms and defensive equipment."( 16) This memorandum was followed by another in which Brooks stated that the sidearm was not to become a "standard item of the uniform" and referred to the wearing of sidearms as exhibiting a "hard" law enforcement image. Brooks included in his memorandum a quotation from one of his superintendents which read in part "...the ranger who wants to wear a sidearm to fulfill an image of himself as a 'law officer' is, in our judgment, not measuring up to the ranger image or the goals of the Service."(17) In 1976 there was an incident which clearly demonstrated the polarization of attitudes concerning the role law enforcement was to play in the Park Service, and again sidearms were the focus of attention. To assist the park rangers with crowd control during the July 4th Freedom Week festivities at Philadelphia's Independence National Historical Park, an eight-man team of rangers was brought in from Fort McHenry, where they had been temporarily assigned to handle the celebration there, as well as a team of 40 rangers from the Southeast, Southwest and Mid- Atlantic regions. These two teams were summoned to respond to a "law enforcement emergency," and because of what they perceived as the nature of their assignments, these rangers felt they should be armed at all times.(18) However, the staff at Independence and the Mid-Atlantic regional director felt that the situation did not require arming rangers during daylight hours. The team members were told to comply with the weapons policy or go home.(19) They stayed, but according to the report filed after the event, they "...worked out much less effectively."(20) Whether that assertion is true or not is, of course, open to debate. Nonetheless, the situation did clearly demonstrate the difference of opinion as to what the NPS ranger "image" should project. The Ranger Image Task Force In an attempt to resolve some of the dilemmas created by the changing law enforcement role of the park ranger, then Director Gary Everhardt established a special task force in 1976 to study the image of the park ranger and to "...formulate a policy statement and define appropriate procedures..." for carrying out the law enforcement mission. The purpose of this task force, headed by Western Regional Director Howard Chapman was to define the role of the ranger so that the specialized skills required for law enforcement could be developed without creating a police subculture within the Park Service.

This task force involved itself with issues very broad in scope and not only attempted to define the role of the ranger and the relationship of law enforcement to that role, but also made recommendations pertaining to equipment, training, reporting procedures, and the perceived impact of police functions on the park system as a whole.(21) In striving for this balance between law enforcement and the other ranger responsibilities, the task force made certain recommendations which were thought by some to conflict with specialized law enforcement functions. A few of these conflicts involved suggested modifications of police equipment specifications to fit perceived organizational image requirements of low key law enforcement. As usual, the wearing of firearms was one of the more emotional issues in the debate over the ranger image. This time it centered around a report recommendation that all sidearms have a barrel length of two inches in order to make them less noticeable to the public.(22) Another conflict arose from the recommendation that the park ranger badge, which had been part of the uniform since 1916, should be worn by only those rangers qualified to engage in law enforcement activities. Of course, this meant that superintendents, interpreters, resource managers and other uniformed personnel not qualified to enforce the law would have to give up their badges. The complaints about this proposed change and the fears about a burgeoning law enforcement subculture were immediate and predictable, and the recommendation was never implemented. In response to the task force report, Western region solicited the assistance of a consultant to evaluate the park ranger image vis a vis his/her law enforcement role. Again guns became an issue: this report countered the two-inch barrel recommendation with some documentation that four-inch revolvers were superior and preferred by 88% of supervisors and rangers in the region. The same poll indicated that 100% of these rangers preferred to wear handcuffs on the belt instead of in the pocket, as was the policy at several parks in the region.(23) In spite of some controversial points, the Law Enforcement Task Force made several good recommendations concerning the expansion of the ranger's law enforcement reponsibilities; it pointed the way toward many good solutions and suggested several viable options for future law enforcement planning. In April 1977, the report was approved by Director Everhardt. The GAO Report In 1976, those supporting a greater law enforcement role for the park ranger received unexpected support from a General Accounting Office (GAO) Report on "Crime in Federal Recreation Areas." This report was based on a study of six governmental agencies which administer federal recreation areas, including the National Park Service. The report concluded that crime in these areas was a serious problem and that agencies responsible for protecting the visitors should "...develop and implement a program for visitor protection which has as its objective the protection of the visitors and their property."(24) The report also suggested that these programs include law enforcement services to visitors, guidelines and standards (including philosophies, objectives and procedures), information systems, procedures for recruiting and promoting competent people, and adequate training and equipment for law enforcement rangers. In his response to the report, Director Everhardt questioned the finding of the GAO that crime in the national parks was a "serious problem" throughout the system, and he suggested that the recentlypassed General Authorities Act had given the Park Service sufficient law enforcement athority to deal with law enforcement problems in its areas. Furthermore, Everhardt pointed out that the claims of the GAO could instill in the public unwarranted fears about visiting the park areas.(25) Despite any doubts about the validity of the GAO report, it was not long after it was issued that the Park Service began to reevaluate the training of its law enforcment personnel. In 1978 the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center developed a nine-week law enforcement curriculum called "Basic Law Enforcement for Land Management Agencies", the purpose of which was to provide a basic 360 hours of police training to all land management personnel with enforcement responsibility, including National Park Service rangers. The Federal Law Enforcement Training Center had evolved in 1970 as a joint interagency effort to provide quality police training for federal officers faced with the increasing law enforcement demands of the 1970s. The center got its start in Washington D.C. as the Consolidated Federal Law Enforcement Training Center. In 1974 it dropped "Consolidated" from its name and moved to Glynco, Georgia, where it is currently located. Park Ranger Law Enforcement Commissions With the passage of the General Authorities Act in 1976 the Park Service moved to clarify who among its seasonal and permanent personnel would be given the authority to engage in law enforcement activities. Since 1974, the Service had issued "C Cards" to certain employees, designating them as law enforcement qualified. In 1976 this system was disbanded when Acting Director William Briggle issued an order which established two levels of law enforcement authority. Class I authority was to be given to all those who held valid "C Cards" and to members of the U. S. Park Police. Those holding Class I authority would have to have undergone a minimum of 360 hours of law enforcement training either at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center or some comparable institution, or they would have to possess comparable experience. Those who held Class II law enforcement authority were not intended to be armed law enforcement officers but would serve to "...help facilitate the proper management of those park areas which do not have a substantive law enforcement problem..." by being authorized to issue citations for minor infractions.(26) The training for Class II authority was to include a minimum of 40 hours involving specific subject areas. In 1977, before this new commission system was to go into effect, Director Everhardt abolished the concept of Class II authority and approved a recommendation for a minimum requirement of 200 hours of law enforcement training in 18 subjects to apply to both seasonal and permanent rangers engaging in law enforcement activities. The relaxing of the training requirements provided some relief for the park areas, many of which were facing the prospect of inadequate staffing for their law enforcement needs. In 1980 the law enforcement commission underwent yet another change when the Service established a system of three levels of law enforcement authority. The full commission was to require 360 hours of training as developed by the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, and those holding it were authorized to carry out all the law enforcement functions granted them by the 1976 General Authorities Act. The new "seasonal law enforcement commission would require 200 hours of approved law enforcement training and would authorize its holder to carry firearms, make arrests and conduct investigations of minor incidents only. This seasonal law enforcement training is provided at no expense to the Park Service by a handful of approved colleges and universities across the country. The new park protection commission would be similar to the old Class II commission; the required training would be the same and those holding it would be employed to supplement law enforcement efforts by authorizing them to write citations for minor violations.

The present system of three levels of law enforcement authority has been in effect for four years and seems to be working quite well for the parks. During this time it has undergone only slight modifications: the 200 hour seasonal training requirement has been increased to 245 hours, and seasonal rangers are now authorized to become involved in the warrant-serving process. Resolution of the Gun Issue As we have pointed out, the issue of sidearms often dominated the debates and decisions about the role of law enforcement in the Park Service during the 1970s. In 1975 the Service issued NPS-9, a comprehensive set of guidelines on how law enforcement in the National Parks was to be conducted.(27) The section on firearms skirted the issue of whether or not law enforcement rangers should wear them by giving individual superintendents considerable discretion in determining how and when they would be worn. Thus, rangers with law enforcement responsibilities in some parks wore sidearms all the time, in other parks they were to wear them only after sunset, and in still other parks they were not to wear them at all. Of course, these variations kept the issue of sidearms alive, even after the passage of the General Authorities Act. During these years it was common for the topic of sidearms to be raised at law enforcement in-service training sessions, with many rangers wanting to know why they were not trusted with the carrying of service revolvers "as part of their uniforms." In 1980 the Park Service put the gun issue to rest with the issuance of a revision of NPS-9 which, among other topics, mandated that all rangers engaged in law enforcement activities will be armed.(28) Since then, all the rhetoric about guns has virtually disappeared, and no significant ill effects of the revised policy have surfaced. Enforcement in the '80s: Some Important Issues To Address The decade of the '70s witnessed a rapid growth in the law enforcement role of the park ranger. The Service addressed a need to become more responsive to the problems created by those who, for whatever reason, choose not to abide by the legal and moral guidelines society has established to facilitate its members getting along with each other. This particular element of society seems to be on the increase, even in our national parks. Navigating in previously uncharted waters, the Service moved to fill the need for better law enforcement and visitor protection while at the same time working to keep the law enforcement role in its proper perspective. Certainly, the underlying theme of a meaningful park experience has to be one of perceived personal freedom, and were the Service to allow the development of a police subculture within its ranks it would be jeopardizing one of the very reasons it was established. In retrospect, it appears that the Park Service was successful in achieving both its goals, and, as a group, the rangers of the '80s have incorporated their law enforcement responsibilities into their overall roles with a perspective and a maturity that must appear admirable, even to the most hardened skeptics. To be sure, the Service still has a way to go. One of the recommendations of a follow-up report the General Accounting Office issued in 1982 was that "to the extent feasible (the Service should) remove manpower, resource and policy constraints which impede efficient and effective law enforcement efforts by giving emphasis and support to prevention activities. "(29) The Service is now in the second phase of this role change. The law enforcement rhetoric has subsided, the issues which generated so much disagreement have died away, and the rangers are left with a new set of skills and attitudes that have prepared them to be more effective people managers and keepers of the peace. Whether they are truly prepared for what the future will bring to the parks in the way of deviant behavior, only time will tell. In our judgment, however, the appropriate groundwork has already been laid. Yet some very important issues still remain to be dealt with. One of these involves the burgeoning area of civil liability stemming from activity (or lack of activity) in the law enforcement sphere. As an example, the Park Service does not require that its law enforcement personnel be certified to be free from any psychological disorders that would interfere with their law enforcement duties. It is only a matter of time before this oversight will become a very costly issue in a vicarious negligence lawsuit in civil court. The Service should also be taking a closer look at the concept of the visitor's "reasonable expectation of security." As a public entity which invites the visitors to its premises, the Service assumes some of the responsibility for the safety of their persons and property. Certainly this does not mean that the Park Service should ever become the complete insurer of their visitors, but in situations where harm or loss is foreseeable (such as the car cloutings that occur year after year), it is possible that some liability could be established. Thus, developments like the "Circle of Parks" effort among some of the western parks to reduce car clouting is a step in the right direction. Space does not permit a detailed examination of civil liability as it could be applied to park settings, but suffice it to say that the area is growing rapidly and contains a great deal of very sobering information for park administrators.(30) There are several other issues that need to be dealt with as we continue through the '80s and enter the 1990s; among them are: standardization of law enforcement training, needs-based 40-hour refresher courses, compilation and dissemination of unique Park Service law enforcement incidents which would have value in training and in-service training, visitor abuse of alcohol, better methods for handling juvenile offenders, contingency plans for providing adequate protection in the face of shrinking budgets and manpower, and better strategies for achieving affirmative action goals. It has been said in many circles that, for the Service, the '80s will be the decade of resources protection. Certainly no one would disagree with that, but neither does it mean that it won't also be a decade of people management. With over 300 million visitors to its areas each year, the job of managing people is here to stay. So far we appear to be holding our own. References 1. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Law Enforcement Guidelines NPS-9, 1975, p. 1. 2. U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, "Evolution of the National Park Service Ranger," Horace M. Albright Training Center, Grand Canyon National Park, AZ, 1964. 3. U. S. General Accounting Office Report to Congress, "Crime in Federal Recreation Areas," June 21, 1977. 4. Everhart, William E. (1972) 77je National Park Service, New York: Praeger Press, p. 222. 5. Ibid., p. 224. 6. Ibid., p. 225. 7. McEwen, Walter R. and Wells, Jerry L. (1970) "Law Enforcement in the National Parks," U. S. Park Police Survey, p. 6. 8. Bliss, Donald T., U. S. Comptroller Report to James A. Haley, House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, July 20, 1976. 9. Title 16 United States Code, Section 1(a)(3). 10. Tobin, Daniel J., Jr., Superintendent, Mount Rainier National Park, Memorandum to Howard H. Chapman, Western Regional Director, National Park Service, "Law Enforcement Task Force Report," March 15, 1977. 11. House Report 11887 to accompany Public law 94-458, September 16, 1976. 12. Everhardt, Gary (1976) Memorandum to all employees, "Law Enforcement in the National Park Service," August 13. 13. Kyi, John (1976) Report to James A. Haley, House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, VII: Law Enforcement, April 8. 14. Bliss, Donald T. (1976) U. S. Comptroller General Report to James A. Haley, House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, July 20. 15. Verando, Denzil (1980) "Park Rangers and Law Enforcement," The California Peace Officer, p. 30. 16. Brooks, Chester (1975) Memorandum to Mid-Atlantic Region Superintendents, "Use of Sidearms in Law Enforcement," July 27. 17. Brooks, Chester (1975) Memorandum to Mid-Atlantic Region Superintendents, "Use of Sidearms in Law Enforcement," August 5. 18. O'Guin, Richard (1976) Memorandum to Mid-Atlantic Regional Director, "Law Enforcement Emergency, Freedom Week, June 27 to July 7, 1976," p. 2. 19. Ibid., p. 2. 20. Ibid., p. 4. 21. Law Enforcement Task Force Report, Howard H. Chapman, Chairman (1977) Memorandum to Director, National Park Service, "Law Enforcement Task Force Report," March 15. 22. Ibid., Recommendations Summary, p. 4. 23. Muehleisen, Gene S. (1977) Law Enforcement Task Force Assessment, p. 65. 24. U. S. General Accounting Office Report to Congress (1977) "Crime in Federal Recreation Areas," June 21, p. iv. 25. Everhardt, Gary (1977) Memorandum to Assistant Secretary of the Interior, "General Accounting Office Report On Crime In Federal Recreation Areas," March 1. 26. Briggle, William (1976) Memorandum to all Regional Directors and Director, National Capital Parks, "Law Enforcement Authority," October 12. 27. National Park Service Law Enforcement Guideline, NPS-9, 1975. 28. National Park Service Law Enforcement Guideline, Revised, 1980. 29. U. S. General Accounting Office Report to the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior (1982), "Illegal and Unauthorized Activites On Public Lands — A Problem With Serious Implications." 30. Dwyer, W. O. & Murrell, D. S. (1985) "Security Negligence In Recreation Areas," Parks & Recreation, 20, No. L, 68-72. |

|||||