|

The Interpreter's Handbook

Methods, Skills, & Techniques |

|

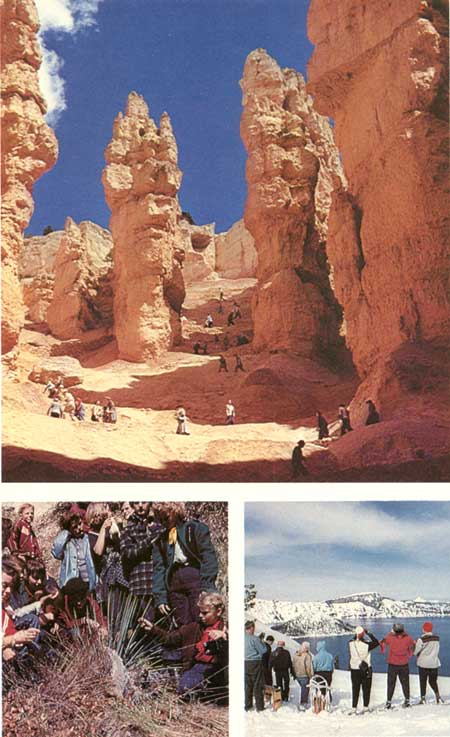

Top-Bryce Canyon National Park. Left-Discovery hike, finding thousands of ladybugs. Right-Winter tour, Crater Lake National Park. (photo by Richard M. Brown) |

CHAPTER 5

Guided Walks and Tours

The guided tour, whether a guided walk, a caravan tour or one taken over snow-covered slopes on skis, is without doubt the most enjoyable interpretive activity an area can offer. It has a special value in that it is usually thoroughly enjoyed by both the visitor and the tour leader. Sometimes an interpretive activity, especially a daily one, can become somewhat of a chore. As days pass, the task may become a routine affair, with the interpreter looking forward to the end of such an arrangement rather than anticipating its beginning. However, such is normally not true of the guided tour. Here the leader can be sure he will not have the same events taking place over and over again every time he goes out, unless he wishes it to be so. New things constantly come to his attention, especially if his guided walk takes him into the field of natural history. Here anything can happen, and often does. The guided walk can well be the peak experience for the visitor in any area, allowing him to see and do something he would otherwise miss. In the out-of-doors he can experience the use of his several senses, something he seldom finds happening in the home environment. A walk has a touch of exploration, of becoming acquainted with things many people never experience. Natural history, history, archeology, environment, ecology—all open new doors of interest to him. In no other interpretive activity is there a greater variety of opportunities for the trip leader to enrich the visitor's experience.

TYPES OF GUIDED WALKS OR TOURS

Guided walks break down into three main categories: the nature walk; the historic house, grounds or building walk; and the archeology walk. Each has its own characteristics and values, with some features common to all.

There must be an objective, if the walk is to be successful. There must be some organization if it doesn't become a mixture of odds and ends of apparently unrelated values. Each walk should have some reason for being, something to contribute to visitor enjoyment and understanding. Some thought or concept must be presented for consideration. Those who go along are likely to know little, or perhaps nothing, of what you are going to tell or show. The possibilities are almost limitless as you contemplate what can be done to enhance their understanding of what they see.

Various types of nature talks have been tried, all successful in varying degrees. Some most often used are:

1. The general nature walk.

This is a "discovery" type, in which the leader simply takes his group along a route that is determined as he goes. He has a spot where he expects to terminate the walk, but usually no pre-determined plan as to just how he will reach it. Everything seen along the way becomes a potential source of interest. It may be a tree, flower, rock, bird, mammal, insect or whatever is to be found. Everyone is encouraged to look for anything that may interest him, and, once found, the leader discusses it with the group. It is a real challenge to the leader, in that many things may be found about which he knows very little.

This type of walk has many fine features, likely the most important of which is that each member of the group can be an active participant. The walk becomes his walk, not just one the leader has dreamed up. It introduces the various group members to new and heretofore unknown natural history subjects, and is an almost perfect lead into understanding the ecological environment.

It does have its weaknesses. Many persons are reluctant to leave an established path or trail. This is especially true in a forested situation, where the unknown may seem to present a threat to persons unfamiliar with such an environment. This is very noticeable among adults who have small children along. There is always the possibility that some less agile person in the group will injure himself.

2. The thematic nature walk.

This is the walk most often used, and is designed to reveal to the group a coordinated concept, natural relationship or similar subject. The leader tries to show how and why something happens in the natural scene. He may wish to demonstrate forest ecology, the influence of man on the forest community, the way in which natural forces are operating, or perhaps the story of a single species of tree, such as the sequoia. The possible list is broad indeed. Such a walk is almost always taken along a pre-determined route which lends itself to development of the chosen theme. The leader knows in advance where he will make stops. This does not mean there will not be unscheduled stops along the way; after all, a bear or some other creature may cross the trail and become the center of attention for several minutes. However, interruptions do not change the basic theme and the leader simply returns to the story he was developing when the interruption occurred.

Its greatest strength lies in the story or thematic approach. It is easy to tie its many facets together in the visitor's mind into a well coordinated whole that will be easy to remember. It is a "safe" type of walk, and seldom does any visitor feel uncertain about venturing along. Most people can "come as you are" without need for any special gear, so the leader can take his group to places many would never venture out to see by themselves.

Its weaknesses are also apparent. This walk tends to lack the individual participation that characterizes "discovery" type walks. There is a tendency for the group to be made up of two units: the leader, and the rest of the party. The leader "tells," the group "listens." Basically there is real danger such a walk becomes the leader's and not the group's. A careful choice of guiding methods used will eliminate this problem. Much depends upon the resourcefulness and experience of the leader.

3. The special walk.

This might be called a "quality" type walk. Many people are interested in special natural history subjects.

Among the most popular of these is the bird walk. The makeup of this group will be varied. There will likely be serious bird students along, as well as a goodly number of people who won't know one bird from another, but who would like to know more. The leader must be reasonably well versed in bird life of the region, not only in the appearance and habits of the bird likely to be seen, but also its call notes and songs. The walk will almost always leave the established trail or pathway. It usually calls for durable clothing and footwear, plus binoculars, if available. It has much in common with the discovery walk, in that its stops are unscheduled and the route may be changed as the walk develops. It is not likely, however, to have people along who are timid about leaving an established trail.

This walk enables you, as its leader, to disclose a whole new world of interest for many people, an interest that can be transferred to where they live, with long time activity a likely prospect. An aid to this type of walk is the small cassette tape recorder, with a cartridge of recorded bird songs and calls of the species most likely to be seen.

The flower walk is another popular one. It can often be accomplished along an established trail. In fact, there is real danger to the plants if the group is allowed to wander into the flower fields. This type of trip is a special favorite among the women visitors, and you should not be surprised to find that men will be in a decided minority in almost any group. Here again, you as the leader will need to know more than just the basic information about each flower species seen. Interesting ecological problems faced by the plant and how it solves them are always well received.

Leading this type of walk is relatively easy, as such a group is normally anxious to see and hear, but not disturb or destroy. I recall one incident, however, where a young naturalist led such a group along a trail through a flower-covered slope. Among other things, he carefully explained the urge sometimes experienced to pick a handful of the colorful creations. About the time he finished, a lady came up to him with a large bunch of flowers in her hand and asked: "Ranger, what kind of flowers are these?" To which the young naturalist (who lost all of his tact and patience at the same time) replied: "Lady, those are picked flowers!"

The forest walk is another that can usually be accomplished along an established trail. Its operation and characteristics are not much different from those discussed above.

The geology walk is quite similar in its treatment to those above, with exception of the guided cave tour.

The latter is carried on in an entirely different environment from other special walks. It requires careful consideration of the group's comfort, as they may be exposed to moisture, chill, and narrow passageways where one's vision is often impaired and a bumped head is commonly experienced. This is another situation where some of your group may feel a bit insecure as they go underground. You must always be prepared for the possibility of electric failure in the cave lights (if so illuminated). The group must be conditioned in advance of the tour that such might conceivably happen, and what should be done if it occurs. Safety thus becomes a major concern to the leader.

The history walk or tour is usually more concise in its planning. Here, you deal normally with fixed objects, or take the party through an area where history was once made. Most of what is shown must be explained. The group is most unlikely to have much background knowledge of the story to be told, although history buffs are frequently members of the tour. You usually have a wide variety of events that you can relate to keep the walk from becoming a simple routine job.

The archeology walk is very similar in planning to the history tour. The story of early man and his activities is a favorite subject with many visitors, and a well thought out tour is a real crowd pleaser. Here again the leader must do most of the explaining, as group background is normally quite limited.

GUIDANCE METHODS

Techniques found effective in leading walks are many and varied. Usually the technique used by the leader is one with which he feels secure. Success depends on his individual skill. Most leaders use one of four methods, or a combination of them. Let us consider each in detail, examining both strengths and weaknesses.

1. Telling

This is the most commonly used of all guided tour methods. Here the leader simply takes his party along a pre-determined route, and usually stops at pre-determined points. At each point of interest, he has carefully assembled in his mind an array of information about the story to be told, and relates this to the assembled group before going on to the next stop. There is normally little group involvement. The leader tells—the group listens. The leader may invite questions before proceeding to the next stop, but even these afford only brief breaks in the time schedule. This method gives the leader complete control of the group, and enables him to keep all the subject material pertinent to the tour. The technique is very popular with tour leaders, especially on history and archeology walks, and also shows up on the nature walks.

If the tour leader has a reasonably good personality, a good speaking voice, and a comprehensive knowledge of his subject, this system is almost always a success. People will leave feeling pretty well pleased with having gone along.

There is a basic weakness in the method, It definitely divides the group into two units—the leader, and the party. The tour is basically his; the group is along to listen and absorb what is being said. There tends to be a lack of group unity. Individuals may relate to the leader, but not so much with each other. The field of interest of each visitor tends to be sharply reduced to conform to that of the leader, with little opportunity to broaden the scope of the subject being presented.

2. Telling and Showing

This is also a popular method with many tour leaders. Basically it is the "telling" with interesting demonstrations added to lend strength to the presentation. A good demonstration is almost certain to be well received, and a number scattered through a guided walk will insure an appreciative audience. Here some individual participation can be utilized, as members of the tour can often be used in the demonstration. "Living history" tours can use this method to advantage. I recall one instance where an old Civil War cannon was the center of attraction. The tour leader asked a number of children about 10-11 years of age to assist him in explaining how the cannon was loaded and fired. Naturally the children were quite ready to do a bit of play acting, so he had no trouble in choosing a "gun crew" from eager volunteers. As he explained to the audience the duties of each member of a gun crew, he assigned a youngster to play that part. When all was ready, he had the "gun crew" go through the motions of "loading" the cannon and finally "firing" it. The whole affair was a rousing success, the audience grasped the story being told, and the children got to play make-believe with an interesting object. Parents of the children involved were pleased their youngsters got to take part. The leader's rapport with the group couldn't have been better.

3. Drawing Out

There is little doubt that this is one of the most effective methods available to a leader. There is also no doubt that it requires him to be more alert and knowledgeable. At the same time, it tends to make him less sure of his ground.

You, as the leader, can choose a wide variety of approaches. If on a nature walk, you can let discovery be the primary focus, you can mix in a thematic approach, or you can include contributions of all kinds. In this method you encourage members of the group to find those things that are of interest to them. One may want to learn more about the ecology of a rotten log; another may wonder about how a bird lives; and another may be interested in some facet of history or early day Indian life. In each instance the leader pursues the subject in some detail, but instead of simply telling the interested person and the group what he knows about it, he draws the answers from the group. This is done by asking questions, the answers to which will throw light on the subject. Here is where the simple, but sage, advice attributed to Kipling is worth remembering:

"I have six faithful working men who help in all I do. Their names are why, what, when, where, how and who."

Ask such questions as: "What is it doing here?" or "how does nature use it?" or "how might man have used it?" or "why is it found here and not somewhere else?" The object, of course, is to start the group to thinking, and someone almost certainly will come up with an answer that will open still more doors for additional questions. Through this questioning method, the important things known about the subject can be brought out. Occasionally you, as the leader, will have to fill in with information that no one in the group is likely to know. You may also have to ask an occasional "leading question" to keep things moving. In the end you have had a very interested group that has worked out its own answers under your direction.

There are real strengths in this method. Basically the walk becomes the group's and not yours. You are still the leader, but you now have a different function. You lead in thought, but the group furnishes most of the information needed. This, in itself, is almost certain to insure success for the walk. Each visitor enjoys getting involved, especially when he knows something about the subject that he can contribute. Every person has an ego, large or small, which he enjoys exercising upon occasion. This method allows him to pamper it a bit!

There are also weaknesses to be considered. The method is time consuming, so the leader must be alert to this fact. Seldom can he set a distance objective and make it as he has planned—if he allows the group to really get involved in the discussion. There is a possibility that someone in the group will try to dominate the trip, but this can happen on any type of tour. Also, some member of the tour may, and often does, come up with the wrong answer, and you, as the leader, must tactfully "rescue" him. If you are really resourceful, you will endeavor to fit his answer into the discussion at a later point.

4. Telling, Showing and Drawing Out.

This obviously combines the three previous methods. It is also the one this writer feels is the most effective of the four. It allows you, the leader, to tell when it is best to do so, demonstrate where you wish, and draw the group into the discussion at any time desired. It allows complete control over the speed at which the tour moves. It allows you to operate on a time schedule, reach a field or building tour objective as planned, and present a well balanced program to everyone.

I see no real weaknesses in this method. It does require a well informed, interested and alert leader to do it well. It is virtually guaranteed to eliminate the "routine" tour. It is definitely stimulating to you and to your group.

OPERATING THE GUIDED WALK OR TOUR

Leading a group of people along a trail, into a natural area, through an historic house or area, or around an archeological site is not difficult, but there is an amazing number of "dos" and "don'ts" to remember if the walk is to be most effectively led. Even the skillful leader will definitely weaken his performance if he overlooks any of these items:

1. Pre-walk activities.

Select a place to meet the group that will be pleasant to those having to wait for the tour to begin. Many persons arrive early for a walk. If you have chosen a bright, sunny place to meet, and the day happens to be a bit on the hot side, members of your group may not be in too good a frame of mind by the time the tour starts. If there is a place where they can sit down, so much the better. If a beautiful view is to be had, still better.

A routed or lettered sign at the meeting place listing time of departure, and days on which the walk is given, is helpful. This is especially true where several guided walks originate at the same point every day. Many visitors try to operate on a time schedule, and information of assistance in planning their activities is useful.

Be sure you have any special equipment along that will be needed, such as binoculars, light meter, etc. If a nature walk, the binoculars are most appropriate. A light meter to help those taking color stills or movies is much appreciated.

Always arrive at the meeting place well in advance of departure time. Remain there and don't wander around, as you will only confuse visitors planning to take the walk. When people arrive at the meeting place they expect to see the person there who will lead the tour. If you do not stay at this location, many may be uncertain as to whether they are at the correct place.

As people arrive, greet them cordially. Don't just let them stand around. A friendly reception helps put them at ease, and is the first step in welding them into a cohesive group.

Engage early comers in conversation, if possible. Don't be "pushy," but get them started talking. It helps make them a part of the group, and puts you on good terms with them before the walk begins. This also helps to get each person acquainted with others on the tour.

By all means, plan to start the walk on schedule. Don't just wait around for possible late comers. Visitors who arrived on time have made an effort to do so, and should not have to wait for less punctual persons.

2. Before the tour leaves.

Introduce yourself before starting the walk. This is not simply a matter of ego; the group will want to know who you are. Make the introduction simple for the group will not be interested in a resume of your achievements.

Identify the activity in which they are to take part. This eliminates the chance that some of them may not be attending the tour they think they are. It also tells the persons who have simply "joined up" what the tour is to be. If the tour is a part of an agency program, be sure to let the group know its name.

State the distance to be covered on the walk and the approximate time required. Some may not be able to make the tour due to physical limitations or lack of time. They should know what to expect before they begin the walk. Be sure that you adhere to the limitations you have indicated for distance and time. Getting back five minutes late is not too serious; arriving a half hour late is inexcusable.

Let them know where the walk is to end. This is especially important if it ends at a different place than where it began. It is most disconcerting to the visitor to find that the tour does not bring him back to his starting point, for he faces a walk back to his car or finding other transportation. He may have someone waiting for him to return. He may be operating on a time schedule with a bus or plane to catch, or he and his family may have planned to depart at a given time.

Inform the group of any special conditions to be met, such as rough terrain, or fees that may be charged while en route. One such tour was found to require boat transportation as part of the walk. The fee for the boat was pretty costly, and several of the group went no farther than the boat dock. Understandably those people were much irritated by the turn of events.

Tell of any special gear that may be needed, such as warm clothing if entering a cave, etc. This is especially important when children are along, as worried parents do not contribute much to the group.

Briefly list some of the highlights to be expected, and the objectives of the walk. Your tour may be an ecological one dealing primarily with nature, or one centered around history, etc.

Invite members of the group to ask questions as the walk proceeds. Otherwise there may be some reluctance on their part to speak to you about things seen or mentioned.

Let them know how the walk is to be led. Do this tactfully, as you are setting up guidelines for them to follow, and you don't want to antagonize anyone. However, there have to be some observances of safety precautions, keeping the group together, the pace that will be set, etc.

3. The guided walk.

Begin the walk leisurely, moving only a short distance from the starting point before making your first stop. This stop should be within sight of where the tour began, which allows late comers to arrive and join. If the tour group is not in sight when late comers arrive, the chances are they will not attempt to overtake you. However, do not drag out the length of this stop.

Walk only as fast as the slowest in the group. Most visitors are not in the "pink" of condition. There may be older persons in the party who cannot move along at more than a leisurely pace. You will have to adjust your timing on the tour to the pace that can be set.

In leading the walk, keep in the lead at all times. Do not let individuals go ahead. Often children will want to run ahead of the party, but this should not be allowed to happen. A tactful approach will usually keep the youngsters in line without antagonizing parents. It should be kept in mind that if you do let them run ahead and an injury should occur, you may well be blamed for the incident.

In using a steep trail, take advantage of switchbacks. One big problem in handling a large tour group is getting them to a position where all can hear. This is difficult on a narrow trail, but if such a trail has switchbacks, it is good technique to stop the group after part of the party has made the turn, thus allowing everyone to hear what is said. If there is no switch-back, you simply stop the group and walk back to the middle of the line, get off the trail (uphill if possible), and speak from this vantage point.

Be sure to collect your group before starting to talk. Too often tour leaders begin speaking before the end of the line has arrived. Naturally those persons miss the opening words about the point of interest at the stop. Failure to consider these persons is apt to cause them to leave the tour.

In talking to the group, speak clearly, don't talk too fast, and don't shout. Many people have difficulty in hearing, so it is important that you enunciate clearly. If you must shout to make yourself heard, you have stopped your party at the wrong place! Stopping close to a waterfall, beside a rushing stream, in a windy area, or near traffic sounds is not a good way to make yourself heard and understood.

Hopefully, stops along the tour route will generate discussions, but these should be kept simple. Don't let them lapse into academic treatments, and be sure to keep them on a level that all can understand. Don't lecture. Involve the group at least part of the time. Draw on listener experience when appropriate, but be prepared to shorten the time, if necessary.

Do not keep your group too long in one place, as many will become restless, and you will have lost some of the group interest you have been developing.

Keep your group together between stops. Don't let them scatter along the tour route. By all means, don't run away from them. Be safe at all times.

Handle humor with care. Planned humor is often easily recognized by the visitor, and sometimes such attempts border on the ridiculous. I recall one tour leader who asked his party, "Have you folks ever seen a tree toad?" No one had, so he walked over to a tree, placed his foot against the trunk, and observed: "Now you are seeing a tree toed!" Needless to say, he began to lose individuals from his party before the walk got very far. Don't be a wisecracker! If a comedian were needed on the tour, the employing agency or firm would undoubtedly have hired one! This does not mean you cannot have fun on the tour, but keep it spontaneous and of a type appreciated by all members.

As tour leader, don't choose certain people to cater to while on the trip. If you wear a uniform and are a man, you can be sure that elderly ladies and young girls are definitely "uniform" conscious. If you are a woman in uniform, you are likely to receive more than passing notice from men in the group.

If on a walk where plants may be part of your story, don't pick specimens to show to the group, as you are setting an example. If you pick plants, you may be sure your act is not overlooked by many on the tour.

Don't be a know-it-all. People resent a person whose attitude shows that he considers himself to be an expert.

Don't be afraid to say "I don't know." Too often a tour leader feels he will "lose face" if he doesn't know the answer to a question and will come up with some sort of a reply. Don't trap yourself! It is most deflating to one's ego to be caught with the wrong answer. No subject is ever so completely mastered that all the answers are known, and the average tour group can ask a vast assortment of questions on many subjects.

Never forget that you are on the tour to help the visitors, not to entertain them. You want them to enjoy themselves, of course, but your task is that of a helpful interpreter, not an amateur entertainer.

4. Termination of the walk.

As you approach the end of the tour, gather the group at a likely place and quickly review something of the scope and interests of the walk. This allows you to reemphasize important points you want them to be sure and remember, It also enables you to tie the entire tour together into a total picture.

If there are announcements to be made, this is the time to do it. Don't make them too lengthy. At this point, most members of the group are aware that the tour is ending and are ready to depart.

Dismiss the group; don't just let them drift away. Unless you do so, some will be reluctant to leave, fearing they will be discourteous. Invite any who wish to stay around with any questions they may have.

OTHER GUIDED TOURS

Two other guided tours, the auto caravan and the ski tour, should be mentioned. The former was once quite popular, but now is seldom used. Ski tours hold considerable promise for the future.

The auto caravan tour calls for special techniques in leading a line of cars. Many of those used on guided walks also apply to caravans. However, there are additional points that should be observed by the tour leader.

Be sure each driver is told how the caravan is to be handled and where it is going. A small tour map is most helpful to give to each driver.

If possible, form a line of cars as each one joins up for the tour. Don't let them simply park anywhere and then try to drop into line when the tour leaves.

Emphasize to each driver that passing is not permissible, although a car can leave the caravan at any time.

Stress safety to each driver. Specify the approximate distance you want between cars, and be sure the driver understands.

In pulling away from the meeting place, and also from all scheduled stops, signal that you are leaving and move out slowly. This allows all drivers to get motors started and form a line. Speed can then be slowly increased as the line starts moving. Thirty-five miles per hour is considered a safe cruising speed along most routes. Use your side-mounted rear view mirror to see that your group is moving properly. Be wary of side roads; someone in your caravan may decide to leave and he could "steal" the line of traffic behind him if you have it stretched out too much.

As you approach a scheduled stop, slow down gradually to allow possible stragglers to catch up. This also tells everyone that a stop is near.

Park your lead car so the middle section of your caravan is approximately even with the point of interest you will discuss. This allows everyone to get out of his car and walk only a short distance to reach the interest point. It eliminates much needless loss of time in getting the group out of cars and back in again.

At your final stop, let everyone know that you will be available for information as to return routes or other things the drivers may need to know.

With the growth of skiing in this country, guided ski tours offer fine interpretive possibilities in many areas. In addition to guiding techniques used on walking tours, the following points should be given consideration. Others will undoubtedly come to your mind depending upon the area chosen for the tour.

Choose a route that is not too difficult or strenuous. Some members of your group may not be too expert on skiis or in the best physical condition. Don't make this a cross-country or mountain climbing expedition!

Your theme can be diversified, but the story of snow is an obvious one.

You are not restricted to formal constructed trails, so your route can visit points that are of unusual beauty in winter.

Watch for stragglers. Getting someone lost in a wilderness situation can be most unfortunate.

Carry a first aid kit. A sprained ankle is always a possibility and blisters are common.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

wnpa/tech/8/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 01-May-2008

Western National Parks Association