|

SHILOH National Military Park |

|

Young Confederate enlisted men from the Washington Artillery

of New Orleans.

From a photograph made prior to

the Battle of Shiloh.

The Second Day

Monday morning, April 7, at daylight, the vanquished of the previous day renewed the struggle with increased strength and restored confidence. Anxious to take the initiative the Union armies were put in motion almost simultaneously, with Buell on the left, Lew Wallace on the extreme right, and Grant's weary troops occupying the space between. The movement began unopposed, except by small unsupported parties which were quickly forced to retreat.

The Confederates had been unable to reorganize their widely scattered forces during the night. Therefore, when the Union advance began on Monday the opposing line of battle was yet unformed. The Confederates were still back in the vicinity of the captured Union camps vainly trying to reorganize their broken commands. They did not succeed in forming a line until after the enemy had advanced beyond the Peach Orchard and the Hornets' Nest, regaining much of the territory they had lost the day before.

The Confederates, one brigade strong, were first encountered by Lew Wallace a short distance in front of his Sunday night bivouac. In a brief but spirited engagement, the Confederates were attacked in front and on the left flank by the Union division. To keep from being surrounded, they fell back almost a mile in the direction of Shiloh Church to take their place in the forming line of battle.

Arrival of Federal reinforcements.

In the meantime, Buell moved his troops rapidly forward until they developed the Confederate line of battle west of the Peach Orchard. The Southerners boldly charged the advancing Union infantry which had moved forward so rapidly that its artillery was still far to the rear. With out artillery support, the Federals were unable to withstand the violent assault of the Confederates and were forced to make a hasty retreat. The timely arrival and effective use of two batteries of artillery permitted the Union line again to advance, only to be driven back once more by the stubborn Confederates.

The battle now raged the entire length of the field. Charge followed by countercharge moved the fitfully swaying line first toward the river and then toward the church. The advantage would seem to test momentarily with the weary Southerners, but would soon be lost to their greatly strengthened opponent. Commands became so intermingled and confused that it was often impossible to distinguish between friend and foe. The Confederates, clad in a variety of colored uniforms, with no well-defined line and on an ever-changing front, suffered the heavier losses from the fire of their own troops.

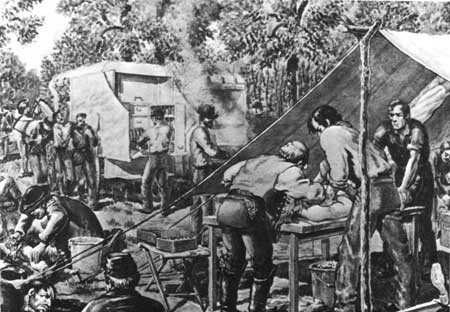

The first tent field hospital ever used for the treatment of the

wounded on the battlefield was established at Shiloh, April 7,

1862.

Meanwhile, General Beauregard, at Shiloh Church, anxiously awaited the return of couriers he had dispatched to Corinth to hurry forward Gen. Earl Van Dorn's army of about 20,000 men, daily expected there from Van Buren, Ark. He had promised to make a junction with General Beauregard as soon as possible, but was delayed because he had no means of transporting his troops across the Mississippi. Unaware that Van Dorn was still in Arkansas, General Beauregard maintained his largest troop concentration in the vicinity of the church to defend the Corinth-Pittsburg Road so that reinforcements could be quickly moved onto the field. As soon as it became known that additional troops were not on the way, Beauregard realized that the road would have to be kept open as a possible line of retreat. The Union commanders were equally determined to drive the Confederates from the position. Consequently, furious fighting raged before the church long after the tempo of the battle had slackened on each flank.

Despite all efforts of the Confederates, the Union line continued slowly to advance. In desperation the Confederates made a gallant charge, first expending their ammunition and then relying on the bayonet. The charge carried the surging line through waist-deep Water Oaks Pond, beyond which the fire from the adversary became so strong that the line was brought to an abrupt halt. Taking cover at the edge of a woods, they repulsed every attempt by the Federals to advance.

By 2 p. m. General Beauregard decided it was useless to prolong the unequal struggle. Since early morning, his lines had been forced back, step by step, with heavy losses. From all parts of the field his subordinates were sending urgent requests for reinforcements, which he was unable to supply. Even his position at the church was in danger of being taken. A continuation of the battle could bring only additional disasters upon his already greatly depleted ranks. To forestall a complete rout, he ordered a rear guard with artillery support to be put in position on the ridge west of the church and instructed his corps commanders to begin withdrawing their troops. By 4 o'clock, the last of the Confederate Army, or what was left of it, had retired from the field and was leisurely making its way back to Corinth without a single Federal soldier in pursuit.

The Union armies did not attempt to harass the retreating Southern columns or attack them when they went into bivouac for the night. Instead, Grant's troops, from the privates to the highest commanders, appear to have been content to return to their recaptured camps, while the Confederates returned to their former positions in and around Corinth to recruit and reorganize.

In explanation of his inactivity Grant said: "My force was too much fatigued from two days' hard fighting and exposure in the open air to a drenching rain during the intervening night, to pursue immediately. Night closed in cloudy and with heavy rain, making roads impracticable for artillery by the next morning."

The next morning, April 8, however, Gen. Thomas J. Wood, with his division, and Sherman, with two brigades and the 4th Illinois Cavalry, went in pursuit. Toward evening they came upon the Confederate rear guard at Fallen Timbers, about 6 miles from the battlefield. The Southern cavalry, commanded by Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, charged the Federals, putting the skirmishers to flight and throwing the Union cavalry into confusion. The Confederates, pursuing too vigorously, came suddenly upon the main body of Federal infantry and were repulsed, after Colonel Forrest had been seriously wounded in the side. Before returning to camp, the Northerners tarried long enough to bury their 15 dead, gather up their 25 wounded, and find out that they had lost 75 as prisoners. The spirited action of the Confederate rear guard at Fallen Timbers put an end to all ideas of further pursuit by the Federals.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |