|

YORKTOWN National Battlefield |

|

Siege of Yorktown

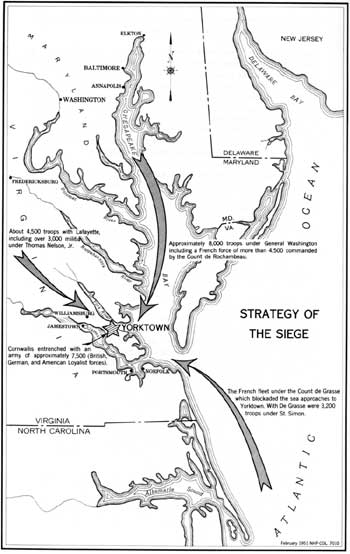

STRATEGY OF THE SIEGE. As the year 1781 opened, Clinton continued to hold New York with a strong force of about 10,000. Washington's force opposing him numbered some 3,500. American leaders saw that recruiting was poor and supplies were low. The whole civilian system on which the army depended had proved loose and difficult, and apathy had come with a long period of inactivity. As the year progressed, change was in the air. There was thought of action and a plan. The commander in chief continued to be troubled, however, by the lack of assistance to the South and the now long-standing inability to achieve anything decisive in the North.

New hope came when the French Government approved additional assistance for the struggling colonies. Already a sizeable naval force was being organized for operations in American waters. The excellent French army corps under the Count de Rochambeau was then at Newport, R. I., to cooperate with Washington. From February 10 to August 14, Washington was engaged with the French in working out a plan of operations. His initial thought, perhaps, was to invest New York should Clinton's position be deemed vulnerable and the expected French fleet move inside Sandy Hook for action. An alternate plan was to attempt the capture of the British force in Virginia or to project an operation elsewhere in the South.

On May 22, 1781, a planning conference was held at Wethersfield, Conn., between Washington and Rochambeau and members of their staffs. A general outline of movement was laid down; but not knowing that Cornwallis was in Virginia or when or where to expect the French fleet under the Count de Grasse, it was necessarily fluid. The plan called for a union of French and American armies for a demonstration against New York—something that might induce Clinton to call troops from the South, thereby relieving, to some extent, the pressure there. This move, executed in July, actually did cause Clinton to ask for troops then in Virginia and resulted in the removal of Cornwallis to Portsmouth, already described.

It was early in June that Washington learned of Cornwallis' move into Virginia. Shortly afterwards, there was more definite word of the plans of De Grasse, although the point at which he would support military operations was not fixed. It was during the first week in July that Rochambeau and his army joined Washington on the Hudson, and some opening moves were made against Clinton in New York. On July 20 Washington entered in his diary that the uncertainties of the situation "rendered it impracticable for me to do more than to prepare, first, for the enterprize against New York as agreed to at Weathersfield and secondly for the relief of the Southern States if after all my efforts, and earnest application to these States it should be found at the arrivl. of Count de Grasse that I had neither Men, nor means adequate to the first object..."

At last, on August 14, Washington received dispatches telling him that the Count de Grasse was to sail from the West Indies with a substantial fleet and 3,200 troops. These troops had been requested by Rochambeau in previous dispatches to Admiral de Grasse. His destination was the Chesapeake; he could be in the area only a short time; and he hoped everything would be in readiness upon his arrival. Washington saw immediately that a combined land and naval operation in Virginia was the only possible plan, and he moved quickly to effect this insofar as he could.

In preliminary maneuvers every attempt was made to deceive Clinton as to the real destination of the units that were now scheduled for operations at Yorktown. These troops included the French Army and units from the American Army, totaling some 8,000 men. The remainder of Washington's force, less than 4,000, under Maj. Gen. William Heath, was left before New York to guard West Point, N. Y, and the Highlands.

The movement toward Virginia began on August 19, 4 days after receipt of definite news from De Grasse. The troops used three distinct and separate routes as far as Princeton, N. J. This was partly to confuse Clinton, who did not fully understand what was happening, until Washington was well under way. Few in the French and Americans camps actually knew the objective. Jonathan Trumbull, Washington's secretary, wrote: "By these maneuvers and the correspondent march of the Troops, our own army no less than the Enemy are completely deceived. No movement perhaps was ever attended with more conjectures, or such as were more curious than this . . . not one I believe penetrated the real design."

From Princeton, the march continued to Trenton where they found there were not enough ships available to transport the men and stores. The decision was to continue on foot to the head of Chesapeake Bay. The passage of the French and American troops through Philadelphia early in September became almost a festive occasion. With the American units leading the way, the trek continued through Chester, Pa., and Wilmington, Del., to Head-of-Elk. It was at Chester, on September 5, that Washington learned that the Count de Grasse had arrived in the Chesapeake Bay with 28 ships of the line, a number of frigates and sloops, and 3,200 troops. At that time these troops, under the Marquis de St. Simon, had already debarked at Jamestown for union with Lafayette's growing force.

On September 8, Washington, Rochambeau, and the Chevalier de Chastellux left to subordinates the task of preparing the allied armies for transport down the bay by ship. They, themselves, proceeded over land to Williamsburg, stopping en route for several days at Mount Vernon. This was Washington's first visit to his home in 6 years. The party reached Williamsburg on September 14, and there was "great joy among troops and people" as Washington assumed active command of the growing American and French forces.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |