|

SCOTTS BLUFF National Monument |

|

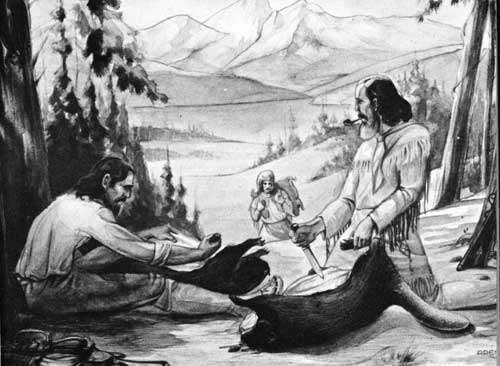

Trappers skinning heaver.

Original sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

The Tragedy of Scotts Bluff

The year 1827 went much as those before, with another rendezvous at Salt Lake where Smith reported his adventures. He then set off on another California trip (followed by a side trip up the Pacific Coast to Oregon, where most of his men were massacred by Indians on the Umpquah). Hiram Scott was among the traders who returned that year to St. Louis. This we know from a document dated October 16, 1827, preserved in the files of the Missouri Historical Society, for Scott is there listed as an employee of Ashley (who continued to operate the supply train), having earned $280 in wages for his season's labor.

That Scott ranked high in the esteem of the fur trading fraternity is attested not only by this document but also by the official records of the Leavenworth Expedition of 1823, wherein Scott shares with Jedediah Smith the distinction of being a "captain of volunteers" under General Ashley. In another document, a letter of April 11, 1827, written by Ashley at Lexington, Mo., Scott is described as "alive to our interest" and "properly efficient." One other source implies that he was a trader of high rank. These meager facts are all we know about Hiram Scott, who was doomed to die mysteriously a year later, while returning with the homeward-bound caravan of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

The facts concerning Hiram Scott's death are even scarcer than those about his career. There is a wealth of tradition and legend, but these cannot be accepted as established facts. Of the innumerable versions almost no two are identical.

The classic account of Scott's death, and the one first published (in 1837), is that given in Washington Irving's story of the adventures of Capt. Benjamin Bonneville, on leave from the United States Army. Irving relates that on June 21, 1832, the Bonneville party

. . . encamped amid high and beetling cliffs of indurated clay and sandstone, bearing the semblence of towers, castles, churches and fortified cities. At a distance it was scarcely possible to persuade one's self that the works of art were not mingled with these fantastic freaks of nature. They have received the name of Scott's Bluffs from a melancholy circumstance. A number of years since, a party were descending the upper part of the river in canoes, when their frail barks were overturned and all their powder spoiled. Their rifles being thus rendered useless, they were unable to procure food by hunting and had to depend upon roots and wild fruits for subsistence. After suffering extremely from hunger, they arrived at Laramie's Fork, a small tributary of the north branch of the Nebraska, about sixty miles above the cliffs just mentioned. Here one of the party, by the name of Scott, was taken ill; and his companions came to a halt, until he should recover health and strength sufficient to proceed. While they were searching round in quest of edible roots they discovered a fresh trail of white men, who had evidently but recently preceded them. What was to be done? By a forced march they might overtake this party, and thus be able to reach the settlements in safety. Should they linger they might all perish of famine and exhaustion. Scott, however, was incapable of moving; they were too feeble to aid him forward, and dreaded that such a clog would prevent their coming up with the advance party. They determined, therefore, to abandon him to his fate. Accordingly, under pretence of seeking food, and such simples as might be efficacious in his malady, they deserted him and hastened forward upon the trail. They succeeded in overtaking the party of which they were in quest, but concealed their faithless desertion of Scott; alleging that he had died of disease.

On the ensuing summer, these very individuals visiting these parts in company with others, came suddenly upon the bleached bones and grinning skull of a human skeleton, which by certain signs they recognized for the remains of Scott. This was sixty long miles from the place where they had abandoned him; and it appeared that the wretched man had crawled that immense distance before death put an end to his miseries. The wild and picturesque bluffs in the neighborhood of his lonely grave have ever since borne his name.

A very touching and pathetic story, but it is quite different from the version offered by Warren Ferris of the American Fur Company. In 1830, he passed Scotts Bluff on the north side of the river 2 years ahead of Captain Bonneville, and just 2 years after the event:

We encamped opposite to "Scott's Bluffs," so called in respect to the memory of a young man who was left here alone to die a few years previous. He was a clerk in a company returning from the mountains, the leader of which found it necessary to leave him behind at a place some distance above this point, in consequence of a severe illness which rendered him unable to ride. He was consequently placed in a bullhide boat, in charge of two men, who had orders to convey him by water down to these bluffs, where the leader of the party promised to await their coming. After a weary and hazardous voyage, they reached the appointed rendezvous, and found to their surprise and bitter disappointment, that the company had continued on down the river without stopping for them to overtake and join it.

Left thus in the heart of a wide wilderness, hundreds of miles from any point where assistance or succour could be obtained, and surrounded by predatory bands of savages thirsting for blood and plunder, could any condition be deemed more hopeless or deplorable? They had, moreover, in descending the river, met with some accident, either the loss of the means of procuring subsistence or defending their lives in case of discovery and attack. This unhappy circumstance, added to the fact that the river was filled with innumerable shoals and sand-bars, by which its navigation was rendered almost impracticable, determined them to forsake their charge and boat together, and push on night and day until they should overtake the company, which they did on the second or third day afterward.

The reason given by the leader of the company for not fulfilling his promise, was that his men were starving, no game could be found, and he was compelled to proceed in quest of buffalo.

Poor Scott! We will not attempt to picture what his thoughts must have been after his cruel abandonment, nor harrow up the feelings of the reader, by a recital of what agonies he must have suffered before death put an end to his misery.

The bones of a human being were found the spring following, on the opposite side of the river, which were supposed to be the remains of Scott. It was conjectured that in the energy of despair, he had found strength to carry him across the stream, and then had staggered about the prairie, till God in pity took him to Himself.

Such are the sad chances to which the life of the Rocky Mountain adventurer is exposed.

The Hiram Scott legend is mentioned by almost all early travelers who have left record of a journey up the North Platte Valley, but it would be fruitless to recite the many other varied, conflicting, and often quaint versions of how he died. There are differences of opinion as to the distance the poor fellow crawled, if any; whether the party traveled on foot or by horseback, muleback, bullboat, raft, or canoe; whether he was a victim of Indians, exposure, drowning, freezing, disease, or starvation; the location of his skeleton; the identity and number of his companions; whether their desertion was premeditated; whether it was justified; how their treachery was exposed; and, finally, whether the whole thing might not have been a grisly hoax!

It was not a hoax. Though the legend has become hopelessly confused, research has proved that there was a Hiram Scott prominent in the Rocky Mountain fur trade from 1823 until 1827; and that he disappeared in 1828 and was never heard from thereafter, except through the faint echoes of the legend. His companions remain unidentified, but research strongly suggests that William Sublette was the leader of the 1828 caravan, who issued instructions to these men to remain with him; and it was William Sublette who led the springtime caravan of 1829 that discovered Scott's skeleton, miles away from the spot where they reported he had died.

Dome Rock from summit of North Bluff.

Rufus B. Sage, who passed the bluff in 1841, was particularly impressed with the melancholy circumstances of Scott's death, and was moved to impassioned poetry:

No willing grave received the corpse

of this poor lonely one;—

His bones, alas, were left to bleach

and moulder 'neath the sun!The night-wolf howl'd his requiem,—

the rude winds danced his dirge;

And e'er anon, in mournful chime

sigh's forth the mellow surge!The spring shall teach the rising grass

to twine for him a tomb;

And, o'er the spot where he doth lie,

shall bid the wild flowers bloom.But, far from friends, and far from home,

ah, dismal thought, to die!

Ah, let me 'mid my friends expire,

and with my fathers lie.

The mountain men have engraved their names on the topography of the West with such place names as Scotts Bluff, Jackson Hole, Colter Bay, Bridger Pass, Sublette County, Provo, Ogden, and Carson City which forever remind us of these colorful figures with seven league boots who spearheaded the invasion of the West.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |