|

SCOTTS BLUFF National Monument |

|

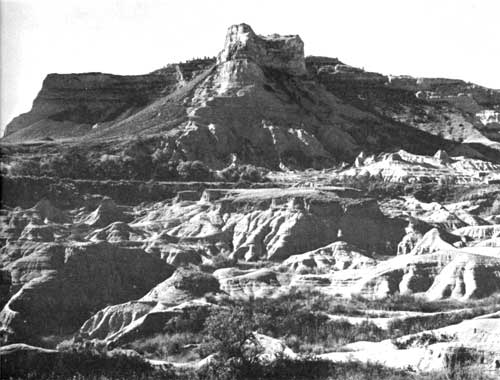

Badlands at the foot of Scotts Bluff's north face.

Courtesy, Union Pacific Railroad.

Natural History of Scotts Bluff

Although Scotts Bluff is primarily significant because of its historical associations, its geology and biology are also interesting. Indeed, appreciation of the history of the bluff is enhanced by an understanding of how this bluff was formed and how it influenced migration routes. An elementary knowledge of the plant and animal life of the area, which is today much as it was in the covered wagon era, adds to your understanding of this story.

Elevations. The highest point in the monument area is South Bluff, 4,692 feet above sea level. (The highest point in Nebraska, more than 5,000 feet, is in Banner County, south of Scotts Bluff.) The "high point" on Scotts Bluff proper is 4,649 feet, which is 766 feet above the North Platte River or 700 feet above the badlands at its immediate base. The elevation of monument headquarters is 4,114 feet.

Geology. This bluff, like the neighboring Wildcat Hills, Chimney Rock, and Courthouse Rock, is an erosional remnant of the ancient Great Plains. These plains were formed by the deposit of gravel, sand, and silt brought down by rivers from the Rocky Mountains after they were uplifted about 60 million years ago. At intervals, 30 to 40 million years ago, volcanoes to the west also added great quantities of ash and dust deposits. When the process of deposit slowed, erosion gained headway, cutting new river valleys in the Plains. High tablelands were left on both sides of the North Platte Valley. Landmarks such as Scotts Bluff and Chimney Rock have hard rock caps that protect them from erosion.

The lower two-thirds of the bluff consists of Brule clay, an Oligocene deposit of buff-colored, soft-textured sandy clay. The badlands formation at the foot of the bluff dramatically demonstrates the rapid erosion of the Brule clay when unprotected by cap rock. The upper one-third of the bluff consists of the Arickaree formation, gray sand beds of the Miocene Epoch. The uppermost Arickaree beds form the top surface of the bluff. These are laced with hard tubular concretions which help protect the bluff and add to the resistance of the beds to weathering. All the formations exposed in the walls of the bluff are interspersed with thin layers of pinkish volcanic ash.

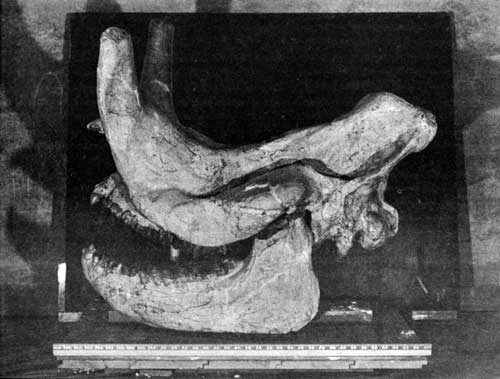

Titanothere skull from the fossil collection, Oregon Trail

Museum.

Paleontology. The Badlands regions of western Nebraska and South Dakota have become world famous for their extensive deposits of fossils of mammals and other animals that lived during the Oligocene and Miocene Epochs of the Cenozoic Era. The Brule clay formation of Scotts Bluff and vicinity is particularly rich in fossil remains of extinct animals of Oligocene age, 30 to 40 million years ago. These exposed remains gave rise to many Indian legends and were frequently noted by curious emigrants. Scientists from many institutions of learning have continued to explore and examine these fossils since 1847, when Dr. Hiram Prout of St. Louis described a jawbone brought to him by a fur trader as that of a Titanothere, a giant rhinoceros-like creature.

Among the most common fossils of the Scotts Bluff vicinity, now in the collections of the Oregon Trail Museum, are giant turtles, pig-like Oreodonts, ancient forms of rhinoceroses saber-toothed tigers, dogs, deer, camels, and rodents. The horse family is represented here by Mesohippus, a three-toed creature about 18 inches in height.

Yucca in bloom at the summit of Scotts Bluff.

Plantlife. The conspicuous trees on the summit and north slopes of Scotts Bluff are ponderosa pine and a juniper usually called Rocky Mountain red cedar. In ravines and along the river banks are cottonwood, willow, and boxelder. The most common shrubs in the area are mountain-mahogany, wild currant, and wild rose. Wildflowers include sunflower, daisies, wild sweetpea, golden banner, penstemon, Indian paintbrush, yucca or soapweed, ball cactus, and prickly pear cactus. The dominant grasses are blue grama, side-oats grama, buffalo-grass, slender and western wheatgrasses, and woolly sedge.

Wildlife. During historic times the North Platte Valley was in the heart of buffalo country, but extermination in the 1870's brought an end to the era of the wild buffalo (bison), which had been the staff of life to the Plains Indians and the main food supply on the white man's frontier. A small captive herd of bison is preserved today in nearby Wildcat Hills State Park. The bighorn and the grizzly, described by early travelers, disappeared by 1860, leaving an occasional rare skull as their last testament. The pronghorn (antelope) is still common in the tablelands north and south of Scotts Bluff, but deer are the only large hoofed animals which still frequent the monument area. Other survivors include red fox, coyote, raccoon, porcupine, badger, beaver, muskrat, and fox squirrel. Prairie dogs, once abundant, have virtually disappeared.

There is a wide variety of bird life. Some of the species that have been seen at Scotts Bluff are—double-crested cormorant, great blue heron, black-crowned night heron, mallard, green-winged and blue-winged teal, American merganser, turkey vulture, red-tailed hawk, golden eagle, sparrow hawk, killdeer, spotted sandpiper, Franklin's gull, mourning dove, great horned owl, (western) burrowing owl, western kingbird, horned lark, cliff swallow, American magpie, rock wren, mockingbird, mountain bluebird, Townsend's solitaire, logger head shrike, western meadowlark, and spotted towhee junco.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |