|

RICHMOND National Battlefield Park |

|

PART TWO

THE FINAL STRUGGLE FOR RICHMOND, 1864-65

(continued)

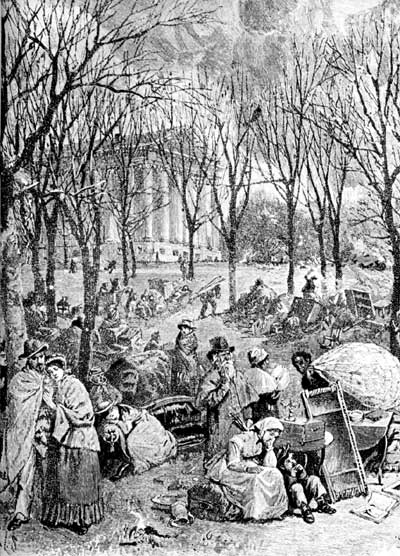

Evacuation of Richmond.

From a

contemporary engraving.

Richmond Falls

Spring came gently to Richmond that year of 1865. The winter had been long and hard. After a cold, wet March, Sunday, April 2, dawned mild and pleasant. The green buds on the trees and the bright new grass put the breath of seedtime in the air; sap flowed warm in the lilac and the magnolia. Under a rich blue sky the people strolled leisurely to church amid the cheerful music of the bells and the soft murmur of the James River falls.

In St. Paul's Episcopal Church, at the corner of Ninth and Grace streets, Jefferson Davis sat in the family pew listening to the sermon. The sexton walked up the aisle and handed him a message from General Lee.

"I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight."

Davis arose quietly and left the church, walked a block down Ninth street to his office in the War Department and gave the necessary orders for evacuation.

Late in the afternoon the official order was posted—then pandemonium reigned. Trunks, boxes, bundles of every description were piled on the sidewalks and in the streets. Wagons, carts, buggies, anything that had wheels and could move, were loaded and raced through the city to fight their way across Mayo's Bridge in the mad rush to cross the James and flee south.

A frantic mob trampled each other without mercy and jammed the streets leading to the railroad stations, only to be turned back by soldiers' bayonets. The few trains that would manage to leave were reserved for government officials, archives, the treasury, and military personnel.

Early in the evening the character of the crowds began to change. From a city of less than 38,000 before the war, Richmond now had over 100,000 people jammed into every available nook and cranny. They had come by the thousands to work for the various government departments and in the munitions factories. Refugees from the many battles fought in Virginia had poured in, as well as the sick and wounded, followed inevitably by deserters, spies, criminals, gamblers, speculators, and derelicts of every kind.

And now the cheap hotels, saloons, and gambling dens began to empty their customers into the streets, many of them half drunk.

All semblance of law and order disappeared. When the guards at the State penitentiary fled, the prisoners broke loose to roam the city at will. The provost guard took the prisoners of war from Libby Prison down the river to be exchanged. This left only the Local Defense Brigade, consisting of government and munitions workers. But most of them were required in government buildings to pack and burn records; some guarded the railroad depots, while others were engaged in destruction assignments. The order had been given to burn all tobacco and cotton that could not be removed by tossing flaming balls of tar into the warehouses along the riverfront.

In the meantime, Mayor Mayo and the city council had appointed a committee in each ward to see that all liquor was destroyed, and shortly after midnight they set to work. Casks and barrels of the finest southern bourbons were rolled to the curbs, the tops smashed open and left to drain.

Like flies around honey, the mobs swarmed and fought their way into the streets where the whiskey flowed like water. Men, women, and children, clawing and screaming, scooped it up with bare hands, or used pails, cups, basins, bottles, anything that would hold the amber liquid. They used rags on sticks dipped in whiskey for torches, and went howling through the city in search of food and plunder like a pack of mad wolves, looting, killing, burning.

The soft night sky became pink, then turned a dull red. The blaze from the Shockhoe Warehouse at Thirteenth and Cary streets, where 10,000 hogsheads of tobacco was put to the torch, flew skyward as if shot from a huge blowtorch. The flames quickly spread to the Franklin Paper Mills and the Gallego Flour Mills, 10 stories high. Higher and higher they soared, and then widened until it seemed a red hot sea of fire would engulf the whole city.

A faint hot breeze began to stir from the southeast, scattering burning embers through the streets and alleys and houses. Powder magazines and arsenals let go with a whooshing boom. Thousands of bullets and shells tore through buildings and ploughed up the streets. Shells exploded high in the smoke cascading a metal spray over the area, followed by the rattle of bursting cartridges in one great metallic roar. Just before daybreak a deafening explosion from the James River signalled the destruction of the Confederate warships and the Navy Yard.

Richmond was now one vast inferno of flame, noise, smoke, and trembling earth. The roaring fire swept northwestward from the riverfront, hungrily devouring the two railroad depots, all the banks, flour and paper mills, and hotels, warehouses, stores, and houses by the hundreds.

About dawn a large crowd gathered in front of the huge government commissary at Fourteenth and Cary streets, on the eastern edge of the fire. The doors were thrown open and the government clerks began an orderly distribution of the supplies. Then the drunken mob joined the crowd.

Barrels of hams, bacon, flour, molasses, sugar, coffee, and tea were rolled into the streets or thrown from windows. Women ran screaming through the flames waving sides of bacon and whole hams. Wheelbarrows were filled and trundled away. When the building finally caught fire from the whiskey torches, the mob swarmed into other sections of the doomed city where the few remaining clothing, jewelry, and furniture stores were ruthlessly looted and burned. A casket factory was broken into, the caskets loaded with plunder and carried through the streets, and the fiendish rabble roared on unchecked.

As the drunken night reeled into morning the few remaining regiments of General Kershaw's brigade, which had been guarding the lines east of Richmond, galloped into the city on their way south to join Lee in his retreat to Appomattox. They had to fight their way through the howling mob to reach Mayo's Bridge. As the rearguard clattered over, Gen. M. W. Gary shouted, "All over, good-bye; blow her to hell."

Richmond burns.

From a contemporary sketch.

The barrels of tar placed along the bridge were promptly put to the torch. Soon tall flames shot high into the air, and with the two railroad bridges already burning, the three high-arched structures were like blazing arrows pointing to the very gates of hell.

Then down Osborne Turnpike and into Main Street trotted the Fourth Massachusetts cavalry. When the smoke and heat blocked their path, they turned into Fourteenth Street past fire engines blazing in the street and proceeded up the hill to Capitol Square, where a tragic scene awaited them.

Like a green oasis in a veritable desert of fire and destruction, the sloping lawn around the Capitol was jammed with frightened people seeking safety from the flames. Family groups, trying desperately to stay together, huddled under the linden trees for protection from the burning sparks. Piles of furniture were scattered in every direction—beds, chairs, settees, paintings, silverware, gilt-framed mirrors— the few possessions left, the family heirlooms, the treasures faithfully passed down from generation to generation. In the background the massive white columns of the Capitol, designed by Thomas Jefferson as a replica of the famous Maison Caree at Nimes, stood guard over the huddled masses below.

The soldiers in blue quickly dispersed the mobs at bayonet point. Guards were immediately placed to prevent further looting. The fire was contained by blowing up buildings in its path to create a fire-lane, leaving the main part to burn itself out. By nightfall everything was under control, but most of the business and industrial section of the city was gone.

The stars shone down that night on the smouldering ruins of more than 700 buildings. Gaunt chimneys stood naked against the black velvet sky. A Federal officer, picking his way through thousands of pieces of white granite columns and marble facades that littered the streets to inspect the guard, noted that the silence of death brooded over the city. Occasionally a shell exploded somewhere in the ruins. Then it was quiet again.

A week later Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Va. The war was over.

Richmond after the war.

Courtesy, Library of

Congress.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |