|

FREDERICKSBURG and SPOTSYLVANIA COUNTY BATTLEFIELDS MEMORIAL National Military Park |

|

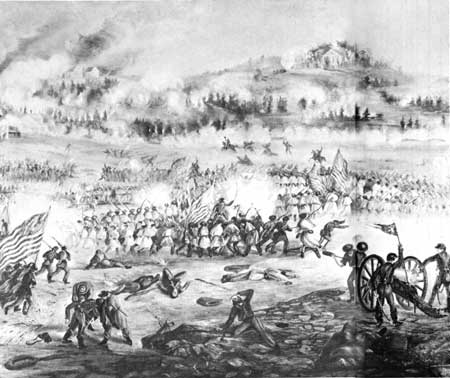

Frederic Cavada, a Union lieutenant, recorded

Sumner's vast and futile charge against the strong Confederate line

along Marye's Heights on the afternoon of December 13.

Courtesy

of Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

"THAT TERRIBLE STONE WALL"

Sumner, on the Federal right, fared even worse. On Marye's Heights and in the sunken road behind the stone wall at the base of the Heights, Longstreet had placed Ransom's division and Cobb's Georgia brigade of Gen. Lafayette McLaws' division.

As Gen. William French's division of Couch's II Corps formed for the attack on the edge of the city, it came under a devastating artillery fire from the Confederate guns on the surrounding hills. Then as the brigades swung out in battle formation across the open fields, their alinement was broken by a canal drainage ditch that Burnside obstinately refused to admit existed. The blue line staggered and slowed as men fell like leaves in an autumn wind. Regrouped under fire, the men sprang forward again, passing under the range of the artillery on the hills, only to be met by a sheet of flame as the Confederates behind the stone wall, reinforced by Gen. Joseph Kershaw's brigade, exploded into action. When the smoke eddied away, remnants of the Federal regiments could be seen retreating across the fields to the shelter of a slight rise in the ground.

Burnside stubbornly refused to admit his mistakes. He continued to hurl brigade after brigade against the stone wall, first committing to action Gen. Winfield Hancock's division, then Gen. Oliver O. Howard's and later two divisions from the IX Corps. As one soldier described it: "They reach a point within a stone's throw of the stone wall . . . that terrible stone wall. No farther. They try to go beyond but are slaughtered. Nothing could advance farther and live."

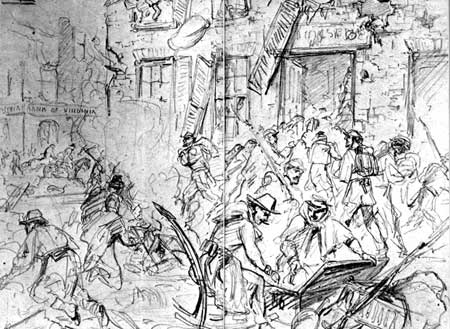

he citizens of Fredericksburg also felt

the war's sharp edge. On December 11 Union artillery heavily damaged the

town, leaving marks still visible today. Other destruction took place

during the brief occupation. Waud sketched these Union soldiers sacking

the town during a night of the occupation.

Courtesy, Historical

Society of Pennsylvania.

It was hopeless and useless, a waste of life, a horrible mistake. Nothing was accomplished by the attack. Darkness mercifully put an end to it. And that night, as the snow lay hard on the hills, many of the wounded slowly froze to death. "It is fearful to wake at night," one veteran wrote, "and to hear the sounds made by the men about you. All night long the sounds go up of men coughing, heavy and hoarse with halfchoked throats, moaning and groaning with acute pain, a great deal of sickness and suffering on all sides . . . ."

Even then, Burnside hesitated. Not until 2 days later did he finally make up his mind to withdraw. During the night of December 15, under cover of a violent rainstorm, the Army of the Potomac retreated across the Rappahannock and went into its old camp on the heights beyond the city. The Federals had suffered 12,653 casualties in killed, wounded, and missing; the Confederates 5,309.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |