|

FREDERICKSBURG and SPOTSYLVANIA COUNTY BATTLEFIELDS MEMORIAL National Military Park |

|

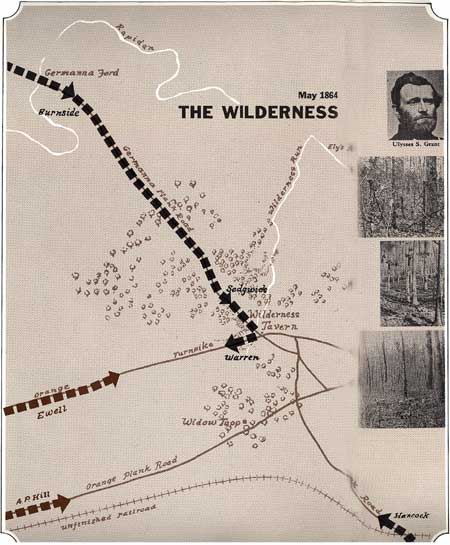

Part II: Grant Begins the Final Drive

WILDERNESS May 1864

Death hung in the air

IN MARCH 1864 President Lincoln appointed Gen. Ulysses S. Grant commanding general of all the Union armies. Said Grant:

In the east the opposing forces stood in substantially the same relations toward each other as three years before, or when the war began; they were both between the Federal and Confederate Capitals. Battles had been fought of as great severity as had ever been known in war . . . from the James River to Gettysburg, with in decisive results.

He hoped to change this situation by putting pressure on all Confederate armies at the same time, something that had never been done before.

Lee's strategy had always been to "risk some points in order to have a sufficient force concentrated, with the hope of dealing a successful blow when opportunity favors." He believed "as the enemy cannot attack all points at one time . . . the troops could be concentrated . . . where an assault should be made." With its interior, or shorter, lines of communication the South could so concentrate its forces.

This is exactly what Grant realized and wished to prevent. The way to prevent the Confederates from concentrating, as he saw it, was to put and keep pressure on all points at all times, so that the South would be unable to continue its thus successful strategy.

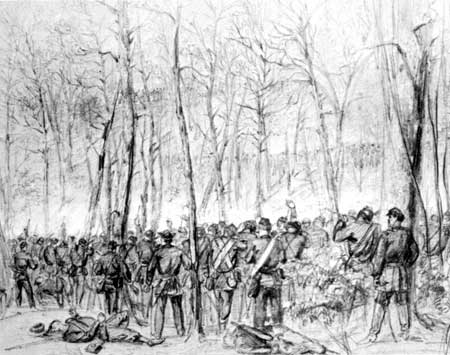

Winslow Homer's painting suggests the vague nature

of the fighting in the Wilderness, where the thickets broke up the

battlelines and the enemy, more often than not, remained

unseen.

Courtesy of New Britain Museum of American

Art.

ONCE MORE INTO THE FOREST

Grant's plan called for Gen. Benjamin Butler to march up the south side of the James River and attack Petersburg or Richmond, or both, and for Gen. Franz Sigel to push down the Shenandoah Valley driving Gen. Jubal Early before him, thereby protecting Washington. Gen. Nathaniel Banks in New Orleans would march on Mobile; Gen. William T. Sherman would cut across Georgia driving Gen. Joseph E. Johnston before him, take Atlanta, and if necessary swing north to Richmond; Meade's Army of the Potomac, with Grant actually in command, was to push Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and capture Richmond. As Grant stated: "To get possession of Lee's Army was the first great object. With the capture of his army Richmond would necessarily follow."

A line of James Wadsworth's Union division goes

into action on May 6. Waud wrote on the drawing that it was near this

spot that the stout old general, much admired by his troops, was

killed.

Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Lee was well aware of Grant's determination. He wrote to Jefferson Davis:

The importance of this campaign to the administration of Mr. Lincoln and to General Grant leaves no doubt that every effort and every sacrifice will be made to secure its success.

He realized that he had to destroy Grant's army before he got to the James River. "If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time." To accomplish this, his strategy was to inflict such heavy losses on Grant that either he would abandon the campaign or the North would become tired of so costly a struggle and not reelect Lincoln.

In this hasty sketch by Waud Francis Barlow's Union

division pushes forward into smoke-filled underbrush on May 6, 1864.

Some of the wounded were carried to safety as Waud depicts below. Others

were consumed by the flames.

Courtesy, Library of

Congress.

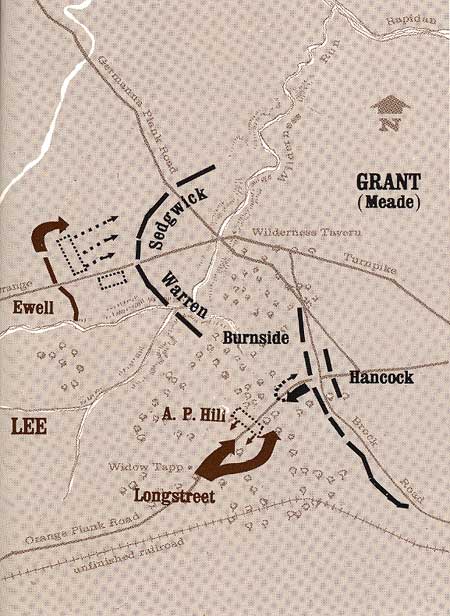

The campaign began on May 4 when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan at Ely's and Germanna Fords and headed into the Wilderness. Grant wanted to turn Lee's flank and get him out from behind his fortifications at Mine Run, farther up the river, so he risked battle in the Wilderness even though he could not use his preponderance of forces to best advantage.

That night Gen. Gouverneur Warren's V and Sedgwick's VI Corps encamped at a strategic crossroads near the Wilderness Tavern. Here the Germanna Plank Road leading south crossed the Orange Turnpike, running east and west. South of the turnpike, but before it met the Orange Plank Road, the continuation of the Germanna Road crossed Brock Road. Hancock's II Corps camped around the crossroads at Chancellorsville, where the Ely's Ford Road met the turnpike. Burnside's IX Corps was still north of the river.

Many of the men remembered later that a sad silence settled over the army that night. The cry of the whippoorwill echoed through the deep shadows. Bones of the unburied dead from the Chancellorsville battle just over a year before gave a gruesome air to the place and sapped the morale of the new men in the blue ranks. Around the campfires in the stillness of the woods, even the veterans were unusually quiet, haunted by memories and premonitions. One recalled that they all seemed to have "a sense of ominous dread which many of us found almost impossible to shake off." Under soft stars the pickets near the Wilderness Tavern heard a rumbling far off to the west and guessed that the Confederates were moving somewhere in the night to meet them.

They guessed right. Because of the size of the Federal forces, Lee did not contest the crossing of the Rapidan. Instead, he planned to strike Grant's right flank in the area of the Wilderness where the Federal artillery would be practically disabled and he could use his smaller force to best advantage.

At the first streaks of dawn the Federal army was on the move. Hancock marched south from Chancellorsville and then angled slightly west to unite with Warren, who then moved south from Wilderness Tavern, followed by Sedgwick. Warren wisely took the precaution of leaving Gen. Charles Griffin's division on the turnpike to guard his right flank while he started his other two divisions south.

As Griffin's men moved west the air became still and sultry, the dry underbrush crackling beneath their feet. From beyond the trees in their front came the dull popping of the skirmishers' guns. Yellow slits of light began to blink along the regimental lines and little balls of smoke, gray and compact, floated upward in the stifling air. Minie balls buzzed among the branches and slapped into the trees. Leaves and pine needles showered down like the first splatter of a sudden summer storm. The whirlwind of battle fast approached.

The Federals ran into Gen. Richard Ewell's corps advancing east on the turnpike, the first of Lee's force to make contact.

As the troops on both sides spread north and south of the turnpike, they disappeared into the twilight gloom of the dense foliage among the gnarled and twisted tree trunks. Soon the woods echoed to the roar of cannon, the crack of musketry, the angry, confused shouts of men trying desperately to kill each other.

When Grant realized that this was more than just a Confederate reconnoitering force on his flank, he quickly suspended the movement south. Warren's other two divisions were ordered back and went into line south of the turnpike on Griffin's left, and Sedgwick was moved north of the turnpike on Griffin's right. Hancock was to swing west and hold the strategic Orange Plank and Brock crossroads, where only a thin line of cavalry patrolled it. But when Lee sent A. P. Hill's corps down the Orange Plank Road, quickly driving off the Federal cavalry, Grant realized Hancock could not get there in time, so Gen. George Getty's division of Sedgwick's corps was rushed over to fill the gap until Hancock could come up.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |