|

FREDERICKSBURG and SPOTSYLVANIA COUNTY BATTLEFIELDS MEMORIAL National Military Park |

|

Part II: Grant Begins the Final Drive

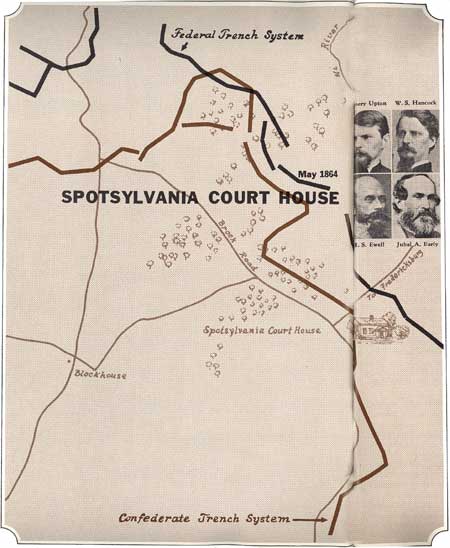

SPOTSYLVANIA COURT HOUSE May 1864

Grant pounds southward

THE FIGHT FOR THE SALIENT

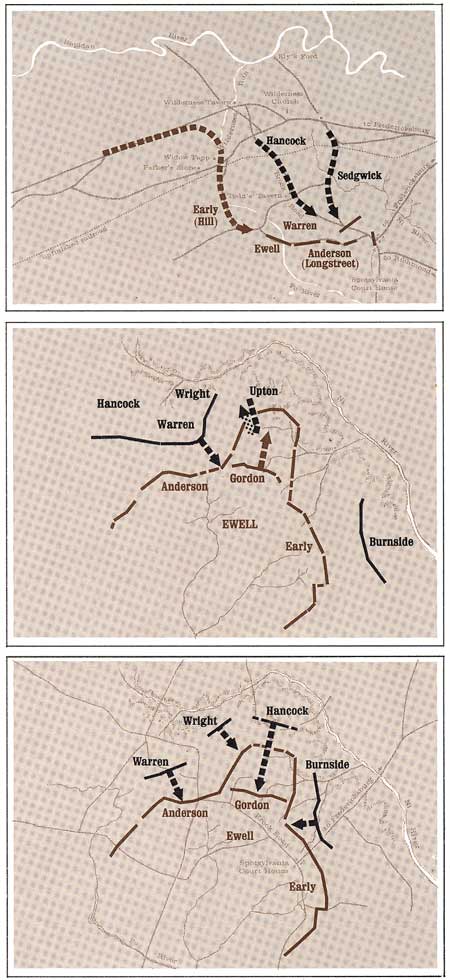

INSTEAD of retreating to lick his wounds as other Federal commanders had done, Grant again decided to move around Lee's right flank by sliding leftward and southward. South and slightly east of the Wilderness area was another strategic crossroads at the village of Spotsylvania Court House. The village itself was just a sleepy hamlet, a handful of houses scattered about a country crossroads, but Federal possession would seriously endanger the Confederate line of communication to Richmond.

During the night of May 7, Warren was ordered to pull out of line and proceed toward Spotsylvania Court House by way of the Brock Road, passing behind Burnside's and Hancock's corps. Sedgwick would follow Warren by way of Chancellorsville and the Piney Branch Church Road to where it met the Brock Road. Burnside would proceed farther east and take the Fredericksburg-Spotsylvania Court House Road. When the rest of the army had moved, Hancock would follow Warren on the Brock Road. The cavalry had been ordered to clear the way.

In the blackness of the night the men stumbled along the unfamiliar country roads, falling into ditches, tripping over under brush, floundering in swamps, walking into bushes and limbs of trees. Some fell asleep marching; imagination played havoc as mirages appeared before tired eyes; a clump of trees became a group of the enemy, a runaway horse, a cavalry charge. Faces of lost buddies seemed to stare out between the silent trees. "It is no small tax upon one's endurance to remain marching all night," one veteran recalled. "During the day there is always something to attract the attention and amuse, but at night there is nothing."

Warren reached Todd's Tavern on the Brock Road about 3 a.m., but here he was halted by Confederate and Union cavalry blocking the road. The delay enabled Anderson's corps to take up an entrenched position on the high ground, about a mile and a half northwest of the vital crossroads. Warren attacked him about 8 o'clock but was beaten back. Later in the day Sedgwick came up and formed on Warren's left, while Ewell formed on Anderson's right just in time to repulse another Federal attack. Then Hill's corps, now under Early because of Hill's illness, formed on Ewell's right, and Hancock came into line on Warren's right.

That night Grant ordered his cavalry, under Gen. Philip Sheridan, to make a raid around Lee's army to disrupt his communications with Richmond, and then to proceed south to reprovision his force from Butler's army south of the James River. Grant believed Lee would be forced to send Stuart's cavalry after Sheridan, and this in effect would protect the Union supply trains from Confederate cavalry raids. Lee did send Stuart after Sheridan, and in a later engagement of the two cavalry forces at Yellow Tavern, on the outskirts of Richmond, Stuart was killed.

The next day, May 9, Grant, misled by reports that Lee was withdrawing from the Federal right, ordered Hancock across the Po River to take Lee in flank and rear. Before Hancock could make contact, however, the mistake was realized, and he was recalled. In recrossing the river he was attacked by Early who had marched from the Confederate right to block his advance. Hancock extricated himself from the dangerous position and went into line again on the left of the VI Corps, now under Gen. Horatio Wright. Sedgwick had been killed by a Confederate sharp shooter. Burnside held the left of the Union army', next to Hancock. Then came Wright and Warren holding the right flank.

(click on images for an enlargement in a new

window)

Lee had Anderson on his left opposite Warren and Wright. Ewell was in front of Hancock, and Early on the right facing Burnside. All were strongly entrenched. There was one weak spot in the line, however. Ewell's entrenchments jutted out in a U-shaped salient beyond the rest of the lines. It was nearly a mile deep and half a mile wide. The "Mule Shoe," as the Confederates called it, made an inviting target.

On May 10 Col. Emory Upton, of Wright's corps, attacked the west side of the salient with 12 picked regiments. He ordered the assault made with four lines of three regiments each. When the first line reached the salient, they planned to fan out left and right to take the Confederate troops in flank, while the remaining regiments went straight ahead to stop any reinforcements that might be sent up. After some brief, but desperate, hand-to-hand fighting, the attack succeeded, but when the expected support from Gen. Gershom Mott's division of Hancock's corps failed to appear, the Federals were forced to withdraw.

Upton's plan had worked, however, and Grant now decided to use the same tactics on a larger scale. Hancock was ordered to break the salient at its weakest point, the apex, supported by Burnside and Wright attacking the east and west sides. Warren would keep pressure on Anderson in his front, at the same time holding himself ready to support the other corps if needed. Again, as in the Wilderness, the whole army was committed to action.

In the predawn darkness of May 12, rain set in, wrapping the area in a sullen mist. The drops ticked off the leaves monotonously as Hancock's men formed for the attack, stumbling through the dark, the rain, and the mud.

Their noisy approach alerted the Confederate pickets that this would be no small attack. Ewell knew that the apex of the salient was his weakest point and had placed 22 guns there. But Lee, misled by a report that Grant was moving around his right flank again, ordered the guns to the rear to be ready to move quickly if necessary. Now they were frantically galloping up to the front again, arriving just in time for 20 of them to be captured without firing a shot.

In the early morning rain, the massed Federal column hit the apex of the salient and broke through, capturing over 3,000 Confederates, while Burnside and Wright assaulted the sides. The blue-clad troops poured through the gap. But, instead of fanning out to the left and right to widen the breach and enable Burnside and Wright to come through, they went straight ahead. Again, as in the Wilderness, Lee appeared on the field to rally his men in this critical moment. If the assault succeeded, the Army of Northern Virginia might be cut in two. But the timely arrival of reserves from Early's corps stopped the advance, and the Federals were driven back to the captured trenches. The heavy fighting raged all day and into the night as Lee vainly sought to recover the position. Although he failed in this attempt, the Confederates did hold until Lee could build new works at the base of the Mule Shoe to straighten his line.

A few hundred yards west of the apex the Confederate trenches made a slight bend to the south. Here the men of Wright's corps came face to face with Ewell's veterans in brutal hand-to-hand fighting. Clubbed muskets and bayonets were used freely, as the rain came down in sheets and the trenches ran red with blood. In some places the wounded and dying of both sides were trampled into the mud in the frantic fighting. "The flags of both armies waved at the same moment over the same breastworks," one soldier noted, "while beneath them Federal and Confederate endeavored to drive home the bayonet through the interstices of the logs. The fire was so intense, that in one instance an oak tree, nearly two feet in diameter, was cut through by bullets . . ." Since that day this area has been known as the "Bloody Angle."

During the night Lee's men withdrew to their new line at the base of the salient. Then a tragic silence settled over the field. In the dark woods, surgeons were busy amputating by the eerie glow of lanterns. The very air was sick and troubled. The night was deep with grief.

A comparative lull settled over the area for the next several days as Grant continued to maneuver his left farther eastward and southward. On May 18 Hancock made a last attempt to break Ewell's new line, but this time the attack was blasted by 30 massed cannon and beaten back before it even reached the Confederate position. The next day Ewell tried to find a weak spot on the Federal right flank but was quickly repulsed. The battle of Spotsylvania Court House was over. Union losses in killed, wounded, and missing were 17,555; Confederate losses are unknown.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |